Lab 4 Exercises

Classifying Rocks

All rocks are classified by just two characteristics: texture and mineralogy. The 20 or so minerals which form most rocks are already very familiar to you, the remaining 6000 are not very common and not significant in rock classification, and you can manage in this course without being able to identify them.

The two main textural terms you will use as you examine rocks in labs 4, 5 and 6 are:

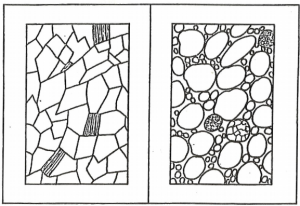

Crystalline: consisting of a network of interlocking crystals. Igneous, sedimentary and metamorphic rocks may have a crystalline texture.

Clastic: consisting of grains eroded from pre-existing rocks. These grains have been transported at least some distance from their place of origin. Only some sedimentary rocks have a clastic texture.

It is essential that you are able to recognize these textures (Figure A). They form the major division between many rocks. Failure to differentiate between a crystalline versus a clastic texture could result in you being responsible for drilling through granite instead of sandstone!

1. Examine samples R2, R151, and R281 and identify the texture of each sample to complete the table below.

| Sample R2 | Texture: |

| Sample R151 | Texture: |

| Sample R281 | Texture: |

The exercises below will guide you through the igneous rock samples in Rock Kits 1 and 2. Review the background information presented in Chapters 4.1 to 4.3 before you begin these exercises. You may wish to consult the Rock Classification Tables at the back of this manual as you complete the exercises below.

Tips for Identifying Igneous Rocks

- Your first step when examining any igneous rock is to look closely at the size of the crystals and to determine if its texture is aphanitic (individual crystals are too fine to be visible with the naked eye), phaneritic (individual crystals are visible with the naked eye), or porphyritic (crystals of two or more distinctly different sizes present). If the sample contains no crystals at all and has a vitreous lustre, its texture can be described as glassy. If the sample contains gas bubbles called vesicles, its texture is vesicular.

- If the sample is phaneritic, or contains phenocrysts, try to identify the minerals within the sample. This will be tricky, as the crystals are much smaller than the samples you examined in Labs 2 and 3. Make sure you examine the sample carefully with your hand lens. You will see much more than with your naked eye alone!

- Start by asking yourself, “how many different minerals can I see in this sample?” and make a short list of the physical properties you observe (e.g., colour, lustre, cleavage).

- Use your observations and the mineral identification tables to identify the minerals present, and make an estimate of their proportions using Figure A in the Rock Classification Tables appendix as a guide. Some mineral-specific hints are outlined here:

- Quartz crystals come in many colours, but quartz always has vitreous lustre and is often translucent.

- Potassium feldspar (K-feldspar) is commonly white or pink in colour, and is often opaque (milky) to semi-translucent.

- Plagioclase feldspar is commonly white to dark bluish grey in colour (depending on the composition), is often opaque (milky) to semi-translucent, and has striations.

- Examining a weathered surface can help to differentiate quartz from feldspar minerals: feldspars chemically weather tend to look chalky and dull (see Figure 5.1.4), whereas quartz always looks glassy. If you look for freshly broken surfaces or edges of the sample you may even see that the feldspar crystals break along cleavage planes while the quartz crystals have conchoidal fracture.

- Muscovite (colourless, translucent) and biotite (dark brown to black) both appear as thin sheets or flakes.

- To tell biotite from other ferromagnesian minerals, test its hardness with a steel file or thin knife: biotite has a Mohs hardness of ~ 2.5-3 whereas amphibole and pyroxene are much harder (H = 5-6).

- It can be difficult to tell amphibole from pyroxene in rocks, as they have similar hardnesses, form blocky crystals, and can be found in similar colours (shades of green to black). Look closely for cleavage: amphibole has 2 planes not at 90°, whereas pyroxene has 2 planes at 90°. If you are unsure whether a ferromagnesian mineral is amphibole or pyroxene and have already identified the other minerals present, it may help to use Figure 4.3.1 as a guide. For example, if you have identified K-feldspar, quartz, and white plagioclase in a sample, chances are the dark coloured blocky mineral you see is amphibole and not pyroxene. Why? Because a felsic magma that is crystallizing K-feldspar and quartz will not normally also crystallize pyroxene.

- Olivine can be distinguished by its vitreous lustre and olive green to yellow-green colour. Caution: weathered olivine may appear dull or rusty (from iron oxide staining).

- If the sample is aphanitic, use the colour of a fresh surface to estimate the composition: felsic rocks are light-coloured (beige, buff, tan, pink, white, pale grey) whereas mafic rocks are dark-coloured (dark grey to black).

- Finally, combine your observations of texture and composition, and use Figure B in the Rock Classification Tables appendix to name the rock.

- If the sample is porphyritic with an aphanitic groundmass, identify the phenocryst mineral(s), interpret the overall composition based on the colour of the groundmass, and name the rock as [phenocryst mineral name] porphyritic [rock name]. For example, a porphyritic volcanic rock with pyroxene phenocrysts in a dark grey aphanitic groundmass is a pyroxene porphyritic basalt.

- Rock names can likewise be modified by other textural terms (e.g., vesicular basalt).

2. Remove samples R1, R2, R11, R21, R31, R41, R42, R51, R61, and R71 from Rock Kit 1 and place the samples on the table in front of you. Arrange these samples according to colour, in a line or into groups. What does the colour of an igneous rock tell you?

3. Keeping the same colour groups you just arranged, within each group arrange the same set of samples according to their grain size (the size of the crystals that make up these rocks). As you examine each sample decide whether:

- all or most of the crystals are large enough for you to see with your naked eye,

- all or most of the crystals are too fine to see clearly with your naked eye, or

- there are no crystals at all (sample is glassy).

4. What does grain size tell you about the cooling history of an igneous rock?

The groups of igneous rocks you just arranged should reflect the classification presented in Figure B in the Rock Classification Tables. Now that you have had a chance to compare all the samples, let’s examine each sample in more detail.

| Sample R1 | Rock name: |

| Sample R2 | Rock name: |

5. It can be useful to look at both weathered and fresh (unweathered) surfaces of a rock sample, as both can be useful when identifying minerals. However, it is important to make note of what type of surface you are describing in your notes. Are you looking at a fresh or a weathered surface?

6. Are these rocks comprised of grains or crystals?

7. These samples are both crystalline rocks (in contrast to clastic rocks which you will be examining in lab 5). Notice the prominent cleavage faces which can be seen on some of the crystals. Which mineral(s) is (are) showing cleavage?

8. Are these rocks aphanitic or phaneritic?

9. Are the crystals all of relatively similar size or obviously different sizes?

10. Describe the colour of the rock:

11. What do you estimate is the percentage of light (non-ferromagnesian) and dark-coloured (ferromagnesian) minerals?

| Non-ferromagnesian: % | Ferromagnesian: % |

12. List below the minerals which you recognize in order of abundance (remember to use your hand lens).

13. Which mineral is responsible for unique colour of sample R2?

| Sample R11 | Rock name: |

14. Are you looking at a fresh or a weathered surface?

15. Choose a term which best describes the texture of this rock:

16. Describe the colour of this rock (light/intermediate/dark):

17. What do you think is the basic difference between specimens R1 and R11?

18. Did sample R11 cool slowly (intrusive) or rapidly (extrusive) compared to R1?

| Sample R21 | Rock name: |

19. Are you looking at a fresh or a weathered surface?

20. Which textural term best describes this rock?

21. The larger crystals in the aphanitic groundmass are called .

22. Do you see cleavage planes on any of the larger crystals?

23. What size (in mm) are the larger crystals?

24. Are these crystals all the same mineral?

25. Describe the overall colour of the rock (light/intermediate/dark):

| Sample R31 | Rock name: |

26. Are you looking at a fresh or a weathered surface?

27. Is the rock aphanitic or phaneritic?

28. Does the textural term, ‘porphyritic’ apply to this rock?

29. Did the rock cool slowly or rapidly?

30. List the minerals in this rock in order of abundance:

31. What do you estimate is the percentage of light and dark-coloured minerals?

| Non-ferromagnesian: % | Ferromagnesian: % |

32. Do you see cleavage planes on any of the minerals? If so, which ones?

33. Describe the colour of this rock (compare the colour to that of R1 and R51):

| Sample R51 | Rock name: |

34. Are you looking at a fresh or a weathered surface?

35. Which textural term best describes this rock?

36. Do any of the crystals exhibit cleavage planes? If so, which ones?

37. What do you estimate is the percentage of light and dark-coloured minerals?

| Non-ferromagnesian: % | Ferromagnesian: % |

38. Would you say that texture (grain size) or mineralogy (mineral composition) is the basic difference between R1, R31, and R51?

| Sample R41 | Rock name: |

39. Which textural term best describes this rock?

40. Do you see any phenocrysts in this rock?

41. Describe the colour of the rock on a fresh surface

42. Is this rock intrusive or extrusive? What evidence supports your answer?

43. What is the basic difference between this rock and R51?

| Sample R42 | Rock name: |

44. Which textural term applies to this sample?

45. What are the small spherical cavities occurring throughout the rock called, and how did they form?

46. What is the difference between this rock and R41?

| Sample R61 | Rock name: |

47. Describe the texture of this rock (Hint: what substance does it resemble):

48. Can you see the individual crystals in this rock?

49. What term best describes the type of fracture of this rock?

This is a sample of obsidian and its texture is due to the super cooling of magma, resulting in a non-crystalline, glassy texture.

50. Compare this specimen to R71 (pumice) which is also a type of glass. How do they differ?

Media Attributions

- Figure A: © Candace Toner. CC-BY-NC.

a rock composed of interlocking crystals

a rock texture consisting of grains of pre-existing geologic material cemented together

an igneous texture characterized by crystals that are too small to see with the naked eye

a rock texture in an igneous rock in which the individual crystals or grains are visible to the naked eye

an igneous texture in which some of the crystals (called phenocrysts) are distinctly larger than the rest

a small open cavity in a volcanic rock, produced by gas bubbles

an igneous texture characterized by holes left by gas bubbles

a relatively large crystal within an igneous rock that is distinctly coarser grained than the crystals forming the groundmass

silica rich (>65% SiO2) in the context of magma or igneous rock

finer grained, typically aphanitic, crystals surrounding distinctly larger crystals (phenocrysts) in an igneous rock that formed from two-staged cooling

Volcanic glass formed by quenched lava in which few (if any) crystals form. Has obvious conchoidal fracture.

a highly vesicular felsic volcanic rock (typically composed mostly of frothy glass fragments)