Chapter 10: Mutual Aid: A Factor in the Evolution of Settlement Work in Canada

Social Darwinism: A Powerful, Persistent Myth

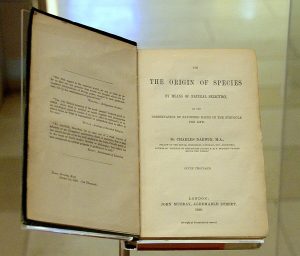

It would be very difficult to engage in a discussion of mutual aid without first exploring the idea that it stands in greatest opposition to social Darwinism. Social Darwinism can be thought of as an application of the ideas first brought forth by Charles Darwin in his landmark study of evolution, The Origin of Species. Although not intended as a treatise on human civilization, Darwin’s ideas were nonetheless taken up by social theorists intent on discussing perceived differences between human races and justifications for social inequities in the world (McKillop, 2016).

I. Herbert Spencer and the “Survival of the Fittest”

The basic tenets of Social Darwinism were primarily based on the works of Herbert Spencer, a prominent 19th-century philosopher, psychologist, and social theorist in England. It was Spencer, not Darwin, who first coined the phrase “survival of the fittest” to discuss how different societies evolved to survive. Ostensibly, this phrase was meant to provide further application of Darwin’s theory of natural selection. In short, natural selection suggests that all life on Earth must undergo a process of adaptation and change in competition for the best sources of food, water, shelter, and other resources.

Regarding the process of evolution, Darwin’s theory suggests that the organisms that are best able to adapt to changes in their environments and compete for scarce resources are those that will survive and reproduce. Darwin’s theories continue to be hugely influential in the study of evolutionary biology and are widely credited with explaining the biological diversity that exists on our planet (National Geographic Society, 2024).

In Darwin’s exploration of the natural world, Spencer saw explanations for what he perceived to be differences in human societies as well. Spencer’s ideas can be seen as parallel to the rise of the notion of meritocracy—the belief that individuals are responsible for their own successes and/or failures in life. In other words, Spencer believed that successful people and/or societies are those who have developed a “competitive” advantage in the world—and have thus “earned” their successes—and will survive into the future. In contrast, those individuals or societies that fail to emerge as the “fittest” survive will not survive. As a result, Spencer’s ideas provided a biological and “scientific” explanation for the existence of widespread poverty, inequality, and exploitation that coincided with the rise of classical economics and the concurrent emergence of industrial capitalism.

(NOTE: Please see Chapter 2: Social Justice in Settlement Work of this book for further discussion on meritocracy and myth-making in North America.)

II. Thomas Malthus and Resource Scarcity

The idea of a meritocratic competition for limited resources in the natural world is also well-aligned with explanations of resource scarcity put forth by Thomas Malthus and other classical economists (Daoud, 2010). Discussions on resource scarcity centred around an understanding that there is a supposed limit to the amount of resources available on Earth to sustain human populations, and as a result, excess population growth will trigger nothing less than a collapse of human societies as we know them (Shermer, 2016). Malthusian perspectives were thus used to justify a series of repressive ideas, including the use of eugenics and forced sterilizations as population control mechanisms by the government.

The fusion of Spencer’s scientific racism with Malthusian scarcity theory led to the Social Darwinist view that social and economic progress could be viewed as an evolutionary, competitive struggle for survival between “fit” and “unfit” groups. Self-interested decisions by individuals under the constraints of resource scarcity would produce the best results for the production (and reproduction) of social progress, and capitalism was thus seen as the best model under which the evolution of humans could occur (Raghavan, 2021).

Social and economic inequities were thus a necessary by-product of “survival of the fittest.” As such, Social Darwinist concepts have been used to justify the idea that the strong are inherently better than the weak and that the success of the strong (and how they came to be “strong”) proves this innate superiority. Furthermore, Social Darwinist perspectives evolved to view strong societies as those that were European, “civilized,” and technologically superior. As such (and for the greater good of humanity), “weaker” societies needed to be invaded, colonized, and/or eradicated by the “strong” to ensure the survival of humanity. This perspective allowed for the rationalization of abuse and genocide directed towards Indigenous populations by invading imperialists and colonizers (South African History Online Collective, n.d.).

III. Pushback From Evolutionary Biology

It is important to note, however, that there has been an enormous amount of pushback against Social Darwinist explanations of human evolution. To begin, the notion of “race” as having a basis in biology has long been discounted in the field of evolutionary biology. Gannon (2016) argues that “race” operates in a contradictory manner: on the one hand, it can be a useful tool for the discussion of human diversity, but on the other hand, it is actually a very poorly defined marker of diversity because there is no clear line defining where one “race” begins and another ends. Assumptions about genetic differences between people of different races have had obvious social and historical repercussions, and they still threaten to fuel racist beliefs (Gannon, 2016).

Similarly, Howard (2016) argues that historically, the concept of race has been viewed as a belief that a person could be determined to belong to a particular group of individuals based on the physical and social similarities they share with other individuals. As such, biological discussions on human race were premised on the idea that there were genetic differences between people of different races, and as such, understanding such differences was key to answering questions on human evolution.

However, despite decades of research attempting to explain biological differences among supposed human “races,” leading scholars in the field of evolutionary biology have come to the exact opposite conclusion. In a sweeping statement in 2019, the American Association of Biological Anthropologists concluded that all humans share 99.9% of the same DNA and that although assumptions have been made about superficial differences among individuals perceived to be from different regions of the world, such assumptions cannot be explained as a result of race-based biology (Fuentes et al., 2019). The statement further notes that “Notably, racial categories have changed over time, reflecting the ways societies alter their social, political, and historical make-ups, access to resources, and practices of oppression” (Fuentes et al., 2019, p. 401).

Although this statement is a definitive refutation of one of the core tenets of Social Darwinism (that of the innate superiority or strength of some human societies and weakness of others), it is equally as important to recognize that significant evidence exists to debunk the Malthusian contention of resource scarcity.

IV. Resource Scarcity or Resource Redistribution?

In addition, contrary to the belief among some that our planet may have already reached a point where it is unable to feed its human population, a large body of research suggests that contrary to a resource scarcity problem, a significant contribution to socio-economic inequity is a resource distribution problem (Stone, 2018) and a production problem that has emerged as a result of ecologically harmful industrial agricultural practices (Smith, 2015). In other words, human population growth has exploded in recent decades, but so has the amount of food humanity has produced to feed this growth.

Further complicating this discussion is the emergence of research in recent years indicating that countries that have a higher standard of living and a less polarized distribution of wealth tend to have smaller families. Roser (2024) indicates three primary reasons for this:

- The general empowerment of women whereby women have greater access to higher levels of education and more overall participation in the labour market

- Declining child and infant mortality rates

- Increasing cost of rearing children, in large part because less pressure is being placed on children in many parts of the world to work to support their families

These trends suggest that critical factors in the development of social inequities in a given society are more related to levels of gender equity and questions pertaining to access to available resources than they are to the inherent “strength” or “weakness” of a given community.

As a result, the number of people that could be supported on our planet cannot be seen as pre-determined or fixed due to a number of variable factors, chief among them being how food is produced, what is consumed, and the environmental impacts of our food production and consumption axis. For example, switching to a more plant-based diet could result in more land being used for crop production that could feed humans directly instead of being used for livestock feed. If that were to happen on a wide enough scale, the United States alone would have the capacity to feed up to 350 million more people (McGuigan, 2022)!

To sum up, Social Darwinism represents an application of Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection (survival of the fittest—those fittest to survive will continue their families’ bloodlines, resulting in the creation of a stronger human species) to the evolution of human society. Social Darwinists contend that human life is a constant struggle for resources and that this competition for survival will ensure that only the strongest members of humanity will be able to reproduce and pass along their evolutionary advantages. This philosophical orientation is fiercely individualistic and justifies the concentration of wealth and power as a demonstration of evolutionary strength.

However, when one considers the balance of evidence discussed above, it becomes apparent that Social Darwinist explanations of human evolution leave much to be desired. But if the “survival of the fittest” does not provide an adequate explanation, what then does? One alternative explanation posits that rather than competition, it is cooperation that has enabled humanity to become the dominant species on Earth.

Learning Activity 1: Cooperate or Compete?

INTSTRUCTOR NOTE: Although this activity can work well in an in-person think-pair-share format, it could also work well as an online discussion forum topic.

On your own, take a few minutes to reflect on social Darwinist perspectives. In your opinion, does the “survival of the fittest” provide a reasonable explanation for the evolution of our species? If so, why? If not, why not? Have there been times in your life when you have acted contrary to social Darwinist perspectives? When and why did you do so?

Keep this list handy because a similar question will be asked of you again at the end of this chapter.

Image Credit

On the Origin of Species, Charles Darwin, London, 1860, National Museum of Scotland by Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin, CC BY-SA 4.0