Chapter 2: Social Justice in Settlement Work

Oppression, Anti-Oppression, and Social Justice

I. Hegemony, “Common Sense,” and Canadian Exceptionalism

The Great Canadian Myth has successfully permeated the values, attitudes, beliefs, and morals of Canadian society and has set the parameters for the common sense knowledge that forms the basis for everyday life (to such an extent that it is very difficult for many Canadians to even think of what a fundamentally different world might look like). Italian social theorist Antonio Gramsci illustrated this concept succinctly through his discussions of ideology and hegemony (Burke, 2005).

For Gramsci, “ideology” refers to the set of broadly accepted beliefs and practices that frame how people make sense of their experiences and live their lives. At its core, ideology attempts to convince people that the world is organized the way it is for the best of all reasons and that society works in the best interests of all. In other words, “common sense knowledge” is a key ingredient of ideology and serves to justify the normalization of the interests of dominant groups (Burke, 2005).

Relatedly, “hegemony” refers to a situation in which all aspects of social reality are dominated by a ruling class who are able to use existing social structures to manipulate how others think, act, and feel. Gramsci argued that the rich and powerful in a society are able to rule more successfully by consent than by force, though force will be used when needed, and this consent results in the majority of people agreeing that inequality is natural (Burke, 2005).

Hegemony is accomplished through the shaping of social values through dominant social and cultural institutions such as schools, mass media, law, churches, and popular culture. If successful, the value systems of the ruling elite thus become internalized as “common sense” and “natural” by others. Gramsci’s conception can help us understand why many people in the world today seem comfortable with the existence of the abject misery of others (Mastroianni, 2002).

Gramsci’s conceptions of ideology and hegemony can also help explain the enduring presence of the Great Canadian Myth and the feelings of Canadian exceptionalism that it continues to generate. In short, Canadian exceptionalism refers to the Canadian government’s continued promotion of immigration, diversity, and multiculturalism in the wake of nationalist populist movements in other Western liberal democracies (Cooper, 2017, p. 4). Among the factors that influence the development of Canadian exceptionalism are geography (Canada has never had unplanned mass migration across its borders the way many other countries have), multiculturalism as official state policy and national identity in Canada, and a well-established settlement sector that assists newcomers with the transition to life in Canada (Cooper, 2017, p. 6).

Such sentiment is bolstered by studies indicating that large cross-sections of the population in Canada support maintaining high levels of immigration and the relatively high percentage of foreign-born residents (Bloemraad, 2012, p. 2). However, a deeper examination of Canadian attitudes towards immigration and multiculturalism and the lived experiences of racialized people living in Canada problematize just how “exceptional” Canadian society is.

For example, a study conducted by Donnelly (2017) indicated that when asked to indicate to what extent the Canadian government should accept applications to immigrate from poorer countries, the majority of participants responded with “some” or “a few,” a level of support that was in line with other Western countries. Similarly, almost half of Canadians surveyed believed there was a correlation between immigration and crime, and slightly less than half of respondents indicated an opposition to ending immigration to Canada entirely (Donnelly, 2017, p. 14).

In addition, research indicates that incidents of poverty, incarceration, and negative interactions with police continue to be disproportionately experienced by racialized people living in Canada. For example, the 2016 Census indicated that 20.8% of racialized people living in Canada lived in poverty, compared to 12.2% of non-racialized Canadians (Statistics Canada, 2016). In addition, racialized workers are more likely to face unemployment or underemployment and are more likely to earn less than non-racialized people (Block, Galabuzi, & Tranjan, 2019, p. 9). For more information, see conversations regarding the immigrant wage gap here, here, and here.

Racialized people also disproportionately experience negative interactions with police and the Canadian justice system. Police in Canada continue the racist practice of carding (or “street checking”), a process of documenting proactive encounters with individuals (Henderson, 2016). Although in theory carding has been justified as a way of protecting public safety, the reality is that Black and Indigenous Canadians are far more likely to be carded by police today than non-racialized people (Huncar, 2017). These negative interactions are further represented in statistics on incarceration. The John Howard Society estimates that Black people are overrepresented in federal prisons by more than 300% (in relation to their proportion of the general population), and that number rises to 500% for Indigenous Peoples (John Howard Society of Canada, 2017).

II. The “Disorienting” of Canadian Exceptionalism

Despite the unfortunate persistence of systemic racism in Canada, feelings of Canadian exceptionalism brought about by the Great Canadian Myth continue. As a result, one of the most important contributions settlement workers can make through their work is in the understanding (and challenging) of these narratives. A process of moral and intellectual reform is therefore necessary by practitioners in the field. This is difficult intellectual labour that must be undertaken and requires a thorough understanding of colonialism and the neoliberal systems of domination that lead to human displacement and migration (Burke, 2005).

Stephen Brookfield’s model for engaging in critical reflection provides a useful starting point for this process, but before proceeding, it is important to understand what is meant by the term “reflective practice.” Hickson (2011) argues that reflection can mean many things in human services. It may mean a process in which a person thinks about something that happened and tries to understand why it did, or it may be a process in which someone is looking to confirm something they are already thinking about. However, reflective practice occurs on two different levels: reflection in action (the thoughts of people while they are involved in a situation) and reflection on action (thoughts that occur later on, where what is considered is not only the events that took place) (Hickson, 2011, pp. 830–831).

Brookfield (2009) expands on this concept to discuss how reflective practice can challenge a person’s way of thinking, being, and knowing. Building on Mezirow’s conception of the disorienting dilemma (Raiku, 2018, p. 3), Brookfield argues that instances that “disrupt” the normal functioning of a person’s life, such as unexpected illness, marital breakdown, or job loss, can cause them to become more aware of (and question) previously unquestioned truths. This questioning can lead to serious consideration of perspectives that challenge “common-sense knowledge” and may ultimately result in the shifting of a person’s thoughts and actions (Brookfield, 2009, p. 296).

Brookfield’s conceptions are particularly useful for settlement workers because they can instigate a deeper analysis of many common-sense assumptions about effective settlement work practice. Shields, Drolet, and Valenzuela (2016) provide excellent explanations of the terms “settlement” and “settlement services.” They define settlement as a “process/continuum of activities that a newcomer goes through upon arrival in a new country. It includes adjustment (getting used to the new culture, language, and environment), adaptation (learning and managing new situations with a great deal of help), and integration (actively being engaged and contributing to the new community)” (p. 5). Settlement services are defined as “programs and supports designed to assist immigrants to begin the settlement process and help them make the necessary adjustments for a life in their host society” (p. 5).

In Canada, settlement services are often tailored to meet the specific needs and circumstances of newcomers. These include services in areas such as language acquisition, counselling on how to access the job market, credential recognition for internationally trained professionals, housing referral, family counselling, health (including mental health) information and linkages, citizenship test supports, access to sports and recreation system navigation, and community engagement. In most cases, these services are provided by various levels of government and government-funded private and/or non-profit organizations, but over the past two decades, dramatic differences have emerged in Canada’s settlement sector (Shields, Drolet, & Valenzuela, 2016, p. 16). Much of this can be attributed to the hegemonic effect of neoliberal reforms in all corners of Canadian civil society.

In short, neoliberalism can be defined as “the agenda of economic and social transformation under the sign of the free market,” and it is an ideology that is synonymous with the commodification and privatization of public sector goods, services, and institutions (Connell, 2013, p. 100). It is important to note, however, that although neoliberal attempts to dismantle the welfare state can be traced back to the 1970s in Canada, it was in the 1990s that neoliberalism emerged as the dominant paradigm in public policy circles.

At its core, this capitalist restructuring of the Canadian state aimed to transform the welfare state into a “lean” state that operated less wastefully and shifted responsibility for the social reproduction of society away from government-run social programs and towards the free market. In other words, the state facilitated the development of a new moral ethos for the responsible citizen—the self-reliant person who was responsible for leading a “lean” life and providing for themselves (Sears, 1999, p. 102).

Social services were privatized, and a new market discipline was imposed on service users and public sector workers alike. The ability to obtain desired services was thus completely dependent on a person’s ability to pay and nothing more. As such, it must be acknowledged that it was the state and its policies of deregulation and privatization that created new markets for neoliberalism to colonize, and not the “invisible hand” of the free market. (Sears, 1999, p. 104).

Neoliberalism’s impact on the settlement sector was profound. Although the economic compatibility between migrants and the Canadian economy has always been a driving factor of immigration policy, new categories of immigrants (such as the Business Class) were created by the government to better identify applicants who could more easily contribute to the local economy and require less support from the government upon arrival (Shields, Drolet, & Valenzuela, 2016, p. 13).

As a result, most settlement service providers now operate under a neoliberalized agency-based model, where workers are expected to provide individualized and/or group-based services. Preston, George, and Silver (2013) contend that this is done at the expense of developing a broader understanding of social issues and forces settlement workers to address the symptoms instead of the causes of marginalization (pp. 645–646).

Learning Activity 3: What Are My Common-Sense Understandings of the World?

Take about 10 minutes to think about some deeply-held “common-sense” assumptions about the world today. As you think about this, ask yourself the following questions:

- When did I develop these understandings?

- How or from whom did I learn these?

- How have these understandings impacted the actions and choices I have taken in life?

- How have I responded to challenges to my “common-sense” understandings of the world?

This activity lends itself best to an in-person small-group breakout or think-pair-share but could also work in a synchronous online learning environment or as an individual reflection.

Learning Activity 4: Disorientation of Common-Sense Knowledge

Take about 10 minutes to recall and reflect on a disorienting dilemma from some point in your life and how it challenged your “common-sense understandings” of the world as it is.

- What was disorienting about it?

- How did you respond to it?

- How did you and your understanding of the world move on from this dilemma?

This activity lends itself best to an in-person small-group breakout or think-pair-share but could also work in a synchronous online learning environment or as an individual reflection.

III. Anti-Oppressive Practice and Further “Disorientations”

Central to successful challenges of common-sense understanding in a neoliberalized settlement sector is a thorough understanding of oppression. Deutch (2009) defines oppression as the experience of widespread, systemic injustice (p. 7). It is embedded in the underlying assumptions of institutions and rules, and the collective consequences of following those rules. Oppression is often a consequence of unconscious assumptions and biases and the reactions of well-meaning people in ordinary interactions (Khan, 2018). It can manifest itself in the following ways:

| Ableism | Oppression that assumes that differently abled people require “fixing” and that their personhood is defined by their disability (Eisenmenger, 2019) |

|---|---|

| Ageism | Oppression based on negative attitudes about a person based on their age (or perceived age), and the default orientation of access to public services towards people who are younger (Ontario Human Rights Commission, n.d.a) |

| Classism | Oppression that discriminates based on a person’s socio-economic class or caste (or perceived socio-economic class or caste) (Class Action, 2021) |

| Homophobia | Systemic discrimination against individuals based on their sexual identity or preference (Planned Parenthood, 2021a) |

| Racism | Systemic discrimination against individuals as a result of their real or perceived ethnicity (Ontario Human Rights Commission, n.d.b) |

| Sexism | Oppression that occurs via through expression of the idea that certain individuals are inferior solely because of their gender (Council of Europe, 2020); it is similar to the concept of misogyny (the systemic hatred of women) (Illing, 2020) |

| Sizeism | Oppression based on a person’s body size and shape (Bergland, 2017) |

| Transphobia | Widespread antagonistic and systemic practices that target transgender individuals (people whose biological sex does not match the gender identity they have assumed) (Planned Parenthood, 2021b) |

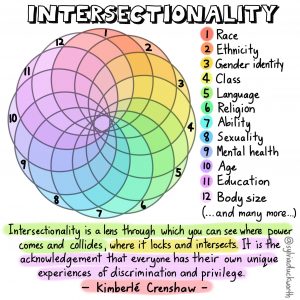

An important concept in the discussion of oppression is intersectionality. Crenshaw (1989) pioneered the term “intersectionality” to refer to instances in which individuals simultaneously experience many intersecting forms of oppression (pp. 139–140). Shannon and Rogue (2009) further elaborated on this definition to describe intersectionality as social identities in terms of race, class, gender, sexuality, nation of origin, ability, age, and so on that are not easily separated from one another. These identities intersect in complex ways as people don’t exist solely as “women,” “men,” “white,” or “working class,” among others. Their identities are determined by a set of interlocked social hierarchies.

All struggles against oppression are therefore necessary components for the creation of a liberatory society (Love, 2010, p. 603). This means it is unnecessary to create a “ranking” of importance out of social struggles and suggest that some are “primary” whereas others are “secondary” or “peripheral” because of the complex ways that they intersect and inform one another. This method of ranking oppressions is divisive and unnecessary and undermines solidarity (the willingness of different individuals or communities to work together to achieve common goals).

Furthermore, intersectionality rejects the idea of a central or primary oppression because all oppressions overlap and simultaneously develop. In an intersectional analysis, a person’s identity is layered, and the presence (or absence) of oppression is context-specific. The same person could feasibly be oppressed in one situation, and the oppressor in another (for example, a black man who is the victim of racism in the workplace but is domestically abusive). What is important is to look at the social forces that are at play and to always remember that the personal is always political (Behrent, 2014).

As a result, it would be difficult to discuss the importance of understanding oppression without understanding privilege. Garcia (2018) describes privilege as unearned social benefits or advantages that a person receives by virtue of who they are, not what they have done. Much like oppression, privilege can also be intersectional; however, because privilege is unearned, it is often invisible because those who benefit from it have been conditioned to not even be aware of its existence. Privilege is thus a very important concept because the relationship that settlement workers have with their clients is of a privileged standing. Settlement workers have the ability to deny people service and access to resources, and as a result, they have power over the lives of the service users they work with.

A thorough understanding of power, privilege, and oppression can help a settlement worker develop an anti-oppressive approach to their professional practice. In short, Clifford defines anti-oppressive practice (a concept pioneered in social work) as the following:

“Looking at the use and abuse of power not only in relation to individual or organizational behaviour, which may be overtly, covertly, or indirectly racist, classist, sexist and so on, but also in relation to broader social structures; for example, the health, educational, political and economic, media, and cultural systems, and their routine provision of services and rewards for powerful groups at local as well as national and international levels” (1995, p. 65, as cited in Burke & Harrison, 2002, p. 132).

Being able to engage in anti-oppressive practice requires settlement workers to be able to deconstruct and challenge the Great Canadian Myth and expressions of Canadian exceptionalism, and to be able to discuss the often-complicated role played by human service professionals in the perpetuation and execution of harmful government policies towards racialized communities (Clarke, 2016, p. 119). As such, an anti-oppressive approach requires settlement workers to reflect on their work with service users and to interrogate the status of expert that has been given to them in their profession (Clarke, 2011).

Furthermore, conventional approaches taken by the helping professions have used deficit-based approaches to providing support to service users. As the name suggests, a deficit-based approach focuses on what a person lacks or needs, and how such needs prevent them from reaching their full potential (Hammond & Zimmerman, 2012, p. 2). By focusing on areas of weakness, human service professionals view a person’s problems as a core part of their identity. These problems mark them as different from people who do not have these problems; as a result, under a deficit-based approach, “problem solving” relies heavily on the expertise of trained professionals.

In contrast, anti-oppressive practice is a strengths-based approach in that the starting point of a conversation with a services user is what they can do, not what they cannot do or are lacking. Strengths-based approaches separate people from their problems and focus more on the circumstances that prevent a person from leading the life they want to lead (Hammond & Zimmerman, 2012, p. 3).

An anti-oppressive approach also takes into account the process of newcomer acculturation into their host countries. Sakamoto (2007) refers to acculturation as the evolution of an immigrant’s cultural belief and value systems towards an orientation that is more in line with their new communities (p. 519). Although the process of acculturation does not occur in a straight line, Sakamoto outlines four different outcomes of the acculturation process (Sakamoto, 2007, p. 519):

| Assimilation | Occurs when newcomers reject their “homeland” culture and accept the “new” culture |

|---|---|

| Integration | Occurs when newcomers accept both their “homeland” and “new” cultures |

| Marginalization | Occurs when newcomers reject both their “homeland” and “new” cultures |

| Separation | Occurs when newcomers accept their “homeland” culture but reject the “new” culture |

Unfortunately, the acculturation hypothesis is insufficient. When applied to a settlement work context, acculturation often takes the form assimilation, as newcomers learn how to become more “Canadianized.” Such dynamics are often practised uncritically in the delivery of settlement services, and when that happens, the responsibility for successful integration completely shifts to the newcomers (Clarke, 2016, p. 215).

However, it is important to note that the successful integration of newcomers to Canada is a two-way process that requires host communities to change and adapt to the cultural differences of newcomers (Canadian Council for Refugees, 1998). In other words, integration is a dialectical relationship in which both parties benefit from an ability to adjust to changing circumstances and work together (Lusk, 2008, p. 3).

If settlement workers are to successfully employ an anti-oppressive approach, it is of vital importance that the perspectives of service users are central to any supports that are offered and that any goals that are set are achieved collaboratively with them. Such collaboration allows the worker–service user relationship to fully utilize not only the professional expertise of settlement workers, but also the expertise that service users have of the circumstances surrounding their leaves and the knowledge gained from their lived experiences (Clarke, 2016, p. 125).

As a result, a core principle of anti-oppressive practice is intersectionality, with settlement workers being required to understand the multiple identities and oppressions encountered by service users (Sakamoto, 2007, p. 528). This stands in stark contrast to efforts aimed at increasing the cultural competence of settlement workers because the journey to cultural competency is individualized and contingent on the understanding of culture through a narrower, more superficial lens (Clarke, 2016, p. 127).

A thorough understanding of how power, privilege, and oppression intersect in the lives of service users can help further destabilize “common-sense understandings” of life in Canada through the linking of personal troubles with larger public issues. When service users are viewed through the lens of partnership in the worker–service user relationship, both the user and worker can utilize their respective strengths to engage in advocacy and social actions designed to advance social justice and bring about systemic change.

Learning Activity 5: Anti-Oppressive Practice Case Studies

Develop an anti-oppressive strategy for working with each of the scenarios below. Identify what challenges your personal experiences and identities may pose and how you would overcome these challenges.

Case Study A: Adaeze

- Adaeze is a 22-year-old woman who was born in Canada to a mother who originally moved to Canada from Nigeria and a father who is “full status” Cree.

- Her relationship to her parents has been strained for much of her life, and it was not uncommon for either of her parents to use physical force to “discipline” her when they saw fit to do so.

- At age 16, she dropped out of high school and moved out of her parents’ home. Although she still interacts with them from time to time, they are not central figures in her life.

- Adaeze is fluent in English but has an incomplete understanding of the Igbo and Cree languages and cultures. She has endured discrimination from members on both sides of her family for her biracial status.

- At age 20, she had a daughter of her own (father unknown), but she didn’t feel ready to take care of the child and put it up for adoption. She has had no further contact with the baby.

- At age 21, she lost her job as a cashier at Superstore for being late too many times, and she has been struggling to stay sober and off the streets since then.

- She has a couple of friends to lean on for support, but when they get together, they indulge in hard partying, which she sometimes regrets.

- She wants to get her life back on track and has come to your office for help.

Case Study B: Min-Jun

- Min-Jun is a 43-year-old man who moved to Edmonton from South Korea three years ago.

- He completed a master’s degree in English literature from a university “back home” but decided that it would be easier for him to earn money in his field if he taught in an English-immersion environment.

- He brought Eun-Kyung (his spouse, age 42) and children (Si-Woo, son, age 15, and Bon-Hwa, daughter, age 12) with him—they immigrated to Edmonton as a family.

- Min-Jun is fluent in English and is a very outgoing person. He has already made connections with Edmonton’s Korean diaspora community. However, he finds the dialect of English spoken in Canada difficult to understand.

- Despite his high level of education, Min-Jun has had a hard time finding meaningful work and has had to resort to taking several survival jobs to pay the bills.

- Recently, he has been having conflict with other members of his family because his spouse is unhappy with their decreased social status and his children are missing their friends back home (and were never in favour of moving to Canada in the first place).

- Min-Jun has no other family in Canada, and although he has a few new friends in Edmonton, he feels intense pressure to show outsiders that the family is “doing well.”

- He feels like his life is starting to spiral out of control and finds himself getting angrier with his family than he wants to be.

These case studies are best worked through as in-class small-group work in synchronous learning environments but can be modified to facilitate individualized learning, and groups can share their plans with their peers.

When the instructor introduces the activity, students should be prompted to identify systemic barriers encountered by service users, what “strengths” and “expertise” service users may have, and how settlement workers can work collaboratively with service users (and thus resist the urge to play the role of “expert” who is helping fill gaps in their lives).

IV. Allyship and Social Justice

Among the most important roles that can be played by a settlement worker is that of an ally. Allyship occurs when a person with privilege attempts to work and live in solidarity with marginalized peoples and communities (British Columbia Teachers’ Federation, 2016). Allies take responsibility for their own education on the lived realities of oppressed individuals and communities and are willing to openly acknowledge and discuss their privileges and the biases they produce (Lamont, n.d.).

Such work can often result in pointed criticisms levelled at allies from the communities they are working in solidarity with, and there is a danger that despite their good intentions, allies can replicate the same systems of marginalization that they are hoping to dismantle. This is especially true of efforts to challenge systemic racism that are lead by BIPOC (Black and Indigenous People of Colour) individuals, but as the following two activities demonstrate, struggles led by members of historically marginalized communities can result in very powerful outcomes in the pursuit of social justice.

Learning Activity 6: Anti-Oppression, Allyship, and Me

When faced with the enormity of responsibly adopting an anti-oppressive perspective towards newcomer supports in Canada, it can feel very overwhelming.

Write down up to three takeaways (or key ideas) that you have learned in this chapter that have pushed you towards a more anti-oppressive perspective.

How have these takeaways shaped your understanding of effective settlement work practice?

This activity would be optimal as a face-to-face “think-pair-share” activity but could be effective as a topic in an online discussion forum as well.

Learning Activity 7: Idle No More → Reconciling Anti-Oppression

Watch the following videos and take notes on key points made.

Discuss the relevance of the Idle No More (INM) movement to our understandings of social justice, anti-oppressive practice, and allyship. What are the implications for settlement workers?

Woodward, S. (2013, January 10). Idle No More documentary – Grounded News [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/IzXI7aznBtc

CBC News: The National. (2012, December 19). Idle No More [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/SpBdZtwH_xc

CBC News. (2017, December 10). How Idle No More sparked an uprising of Indigenous people [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/TYf75dKON6k

APTN News. (2020, January 23). The legacy of Idle No More put Infocus [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/V1DFyCG86ic

NOTE: For more information on the Idle No More movement, click here and here.

This activity would be optimal as a face-to-face “think-pair-share” activity but could be effective as a topic in an online discussion forum as well.

Learning Activity 8: Why Black Lives Matter

Watch the following videos and take notes on key points made.

Discuss the relevance of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement to our understanding of social justice, anti-oppressive practice, and allyship. What are the implications for settlement workers?

Channel 4 News. (2020, June 15). Black Lives Matter explained: The history of a movement [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/YG8GjlLbbvs

TEDx Talks. (2018, April 25). #BlackLivesMatter | Kennedy Cook | TEDxYouth@Dayton [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/Sd-VUOgS3rE

NOTE: For more information on the Black Lives Matter movement, click here, here, and here.

Image Credit

[Intersectionality Venn diagram] by sylviaduckworth, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 Generic licence