Chapter 11: A Relational Approach to Settlement Work Relational Spaces and Practices for Anti-Oppression and Well-Being

Introduction to Reflection and Dialogue Practice

Reflection plays a crucial role in the work of any practitioner. In this chapter, you will find reflection questions designed to help you connect the content to your life experiences, fostering a deeper understanding. Additionally, we introduce the concept of intercultural dialogue as a vital process and practice for settlement practitioners. While reflection centres on your relationship with yourself, dialogue focuses on deepening self-understanding through connecting with others through deep listening. If you are reading this chapter with a group, we recommend taking turns facilitating a dialogue circle using the provided prompts to develop this capacity.

Although a detailed examination of intercultural dialogue is not covered in this chapter, A Manual for Developing Intercultural Competencies: Story [Dialogue] Circles (Deardorff, 2020) is included in the resources at the end. This manual offers practical guidance on the dialogue process, addressing challenges, and using dialogue circles to cultivate intercultural competencies.

Dialogue circles operate on two presuppositions:

- We are all interconnected through human rights.

- Each person has inherent dignity and worth.

(Deardorff, 2020, pp. 17–18)

In addition to the two presuppositions, it is important to remember the following:

- Every person has personal experience that can be shared.

- We all have something to learn from others.

- Listening for understanding (compared to listening to respond) is transformational.

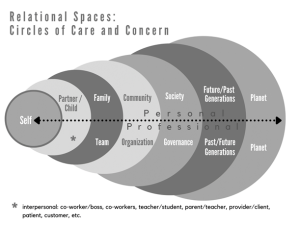

Relational Spaces: Circles of Care and Concern

To initiate our exploration of a relational approach, we begin with the concept of relational space. Relational space is defined here as the co-created, intersubjective space encompassing physical, energetic, psychological, emotional, cultural, and spiritual dimensions, where the dynamics of relationships and identities are held and negotiated.

This model (Mackenzie & Apedaile, 2021), shown in Figure 1, is a visual representation of relational space inspired by Riane Eisler’s (2003) seven partnership relationships, Nell Noddings’ (2013) ethic of care and relational ethics and wahkohtowin, a Cree word that expresses our interrelatedness. This model lays out multiple dimensions of relationships in a nested way that invites systems thinking and calls on us to recognize our interconnectedness. We will use this relational map to reflect on the relational approach throughout the chapter.

Reflection and Dialogue

Notice how the nature and quality of relationships, your identity, and your somatic, body-felt experience shift as you move through the circles. How does your sense of care and concern shift across different relationships, from self to others? What factors generate or weaken that sense?

Pay attention to how the narratives (stories) linked to your identity in different circles, along with communication norms, and the systems and processes that govern these interactions also shift. Consider the relational capacities you need to connect and repair disconnection in different spaces. Now consider how your role as a settlement worker is to support newcomers in connecting and repairing disconnection in a new social, cultural, and political context.

Write an intention or questions you have about a relational approach to settlement work in Canada. Share these with your classmates, then return to them at the end of the chapter.

Image Credit

Apedaile, S. (n.d.). Relational spaces model [Diagram]. Used with permission.