Chapter 1: The History of Settlement Services in Canada

Canada’s Immigration History: Milestones and Stories

Specific Learning Outcomes

By the end of this section, you will be able to

- Examine the historical evolution of government immigration policies and their influence on current settlement practices

- Analyze the historical settlement challenges experienced by groups of immigrants in Canada since the early 1900s

This section of the chapter explores Canadian history from a different lens. It will be explored from the perspective of immigration and settlement. The significant milestones in the history of immigration from the 1880s to 2019 will be reviewed in this section. The first historical milestone covers the period from 1885 to 1923.

| January 01, 1885 | Chinese workers were brought in to help construct the railway, but immigration was restricted by the $50 head tax that was later increased to $500. |

|---|---|

| January 01, 1897 | More than 5,000 South Asians, over 90% of them Sikhs, came to British Columbia before their immigration was banned in 1908. |

| January 20, 1899 | About 2,000 Doukhobors from Russia landed in Halifax en route to farms in the West.

Refugees from Russia, especially Jews, Mennonites, and Doukhobors, settled in Canada. |

| January 01, 1902 | The federal government concluded that the Asians were “unfit for full citizenship … obnoxious to a free community and dangerous to the state” (Canadian Encyclopedia, 2016, para. 5). |

| January 01, 1903 | The head tax for Chinese immigrants was increased to $500. |

| January 20, 1904 | The ban on Chinese immigration was disallowed. |

| October 01, 1906 | The Japanese vessel Suian Maru landed at Beecher Bay on Vancouver Island. The group of 80 men and three women subsequently settled on Don and Lion islands near Richmond, BC. |

| January 01, 1907 | An order-in-council banned immigration from India and South Asian countries. |

| September 07, 1907 | Several hundred people rioted through Vancouver’s Asian district to protest Asian immigration to Canada. |

| January 01, 1923 | The Chinese Immigration Act was replaced by legislation that virtually suspended Chinese immigration on the day known to the Canadian Chinese as “Humiliation Day” (Lee, 2017). |

Milestone 1: Immigrants Build the Foundation and Infrastructure of Canada

Those who settled in Canada as far back as the mid-1600s came from Anglo European (British, Scottish, Irish) and French backgrounds. They were drawn to Canada because of the fur trade and worked for the Hudson’s Bay Company. This group played a role in the development of the first social and economic structures of the newly-formed settler Canadian society.

From the mid-1800s to the early 1900s, labourers were recruited to build the railways and work in factories, and immigrants who had agricultural experience settled in the western and the central Prairies to develop farmland. Immigrants who were recruited for these purposes came from Europe.

From 1867 to 1914 was a period of high immigration. Around 1897, about 2,000 Doukhobors from Russia landed in Halifax, en route to farms in the West. Refugees from Russia, as well as Jews, Mennonites and Doukhobors, settled in Canada, primarily in regions such as the Prairies.

|

Did You Know? Saskatchewan’s population grew by 1124.77% between 1891 and 1911 because of immigration from regional parts of Russia (Widdis, 1992). Manitoba has the largest concentration of Icelanders outside Iceland’s capital city, Reykjavik (Brydon, 1999, p. 686). The Dutch, Germans, and Scandinavians were some of the most ethnically desirable and agriculturally skilled immigrants on the Canadian Prairies (Bicha, 1965, p. 428). |

Stories of Acceptance and Rejection

The social values and ideology of the mid-1800s to early 1900s influenced the creation of policies that blocked non-European immigration but opened the door to people with European backgrounds. A systematic effort to limit non-European immigration resulted in the implementation of the Chinese head tax from 1885 to 1903. Originally $50, the head tax eventually rose to $500, which limited the number of Chinese people who could afford to immigrate. Unfortunately, the head tax legislation continued well into the 1920s, when Chinese immigration was virtually suspended. As noted in the chart above, that legislation by the Canadian government is known by Chinese Canadians as “Humiliation Day”, July 1, 1923 (Lee, 2017), the date the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed. This Act served to exclude further immigration from China to Canada.

Dr. Henry Yu retells his grandfather’s story about how the Chinese head tax and the Chinese Exclusion Act affected his grandfather personally, as well as how it impacted the Chinese community in Vancouver where he had settled. Click here to read his story.

The Chinese head tax is an example of systemic racism. However, it was not considered racist to block immigration based on race at this time in Canadian history.

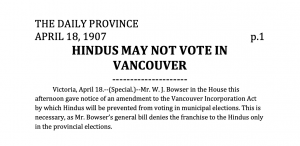

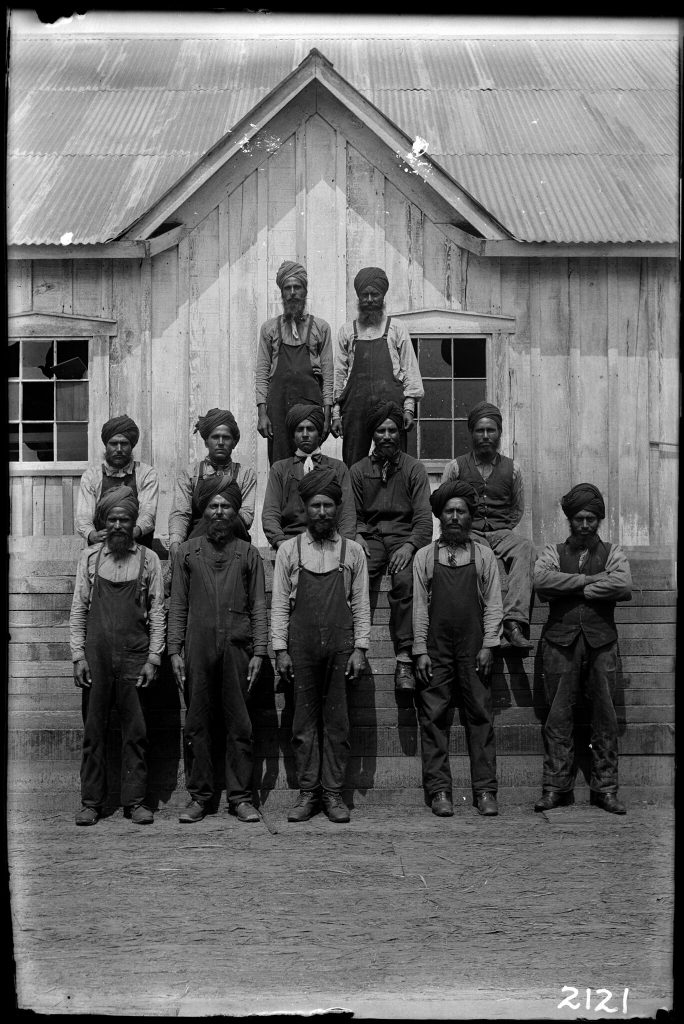

There were some notable exceptions of immigrants from non-European countries who broke through systemic barriers, put down roots in Canada, and left enduring legacies. On January 1, 1897, more than 5,000 South Asians, over 90% of them Sikhs, came to British Columbia. This group was part of a military troop from Hong Kong and Malaysia who were on their way back from London, England, via Atlantic Canada after celebrations for Queen Victoria’s Jubilee. About 45 men eventually came back to settle in the Lower Mainland of British Columbia and across the border in Bellingham, Washington. The number of South Asian men grew from 45 to 5,179 between 1904 and 1908 (University of the Fraser Valley, 2021). They settled in Canada before the immigration of Sikhs was banned in 1908. The newspaper article “Hindus May Not Vote in Vancouver” from 1907 (shown above) demonstrates the prevalence of systemic racism in the Canadian government policies of that time. Despite this effort to ban South Asians from Canada, there is a large community of Sikhs who have established roots in the Vancouver and southern regions of British Columbia.

The video below by Satpal Sidhu is an account of the challenges faced by the South Asian Sikhs and the events that led to the Bellingham riots in 1907. Although many Sikhs ended up in Bellingham, Washington, there was a group of migrants that crossed the American boarder into Canada. This part of Canadian and American history established not only the roots of South Asian Sikhs in Canada, but also the social ideology that influenced the immigration practices of that time.

Sidhu, S. (2014, September 16). We are not strangers documentary about 1907 Bellingham Riots [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mvn_LpXj694&t=306s

This ingrained racism still lingers in today’s society, though not as overtly as it was in the early 1900s. Canadians who may not be aware of this community’s history may still consider South Asians as a recent immigrant group instead of understanding their long history and influence on the development of Canada.

Another part of Canadian Sikh history is retold in a story about the first Sikh immigrant family in Canada. The story is retold in this video called An Act of Grace: UBC’s first Sikh Immigrant Family.

This story further establishes the influence of the Sikh community since the early 1900s.

University of British Columbia. (2016, June 15). An act of grace: UBC’s first Sikh immigrant family [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IUcn8oIejWs

A third group of Asians, the Japanese, have an impactful story that is recounted in a novel called Mikkôsen Suian Maru (The Stowaway Ship Suian Maru), written by Nitta Jiro (1979/1998). Although the novel is fictional, it is based on historical facts about a little-known piece of Canadian Japanese history. On January 01, 1906, a group of 82 Japanese men who were stowaways on the ship Suian Maru landed at Beecher Bay on Vancouver Island. David Kenneth Allan Shulz recounts this piece of history in his thesis Japanese “Entrepreneur” on the Fraser River: Oikawa Jinsaburo and the Illegal Immigrants of the Suian Maru (Sulz, 2003).

There is little documentation about this part of Canadian Japanese immigrant history. James D. Cameron (2005) writes in his article, “Canada’s Struggle with Illegal Entry on Its West Coast: The Case of Fred Yoshy and Japanese migrants before the Second World War,” that the Japanese stowaways were apprehended by the British Columbia RCMP but were eventually allowed to stay because they were considered a source of cheap labour. However, they were not given the same rights and freedoms afforded to Canadians and European immigrants.

The struggles of these two groups of immigrants are important to understand because they reflect the similarity of challenges among non-European immigrants in recent Canadian history. Racism continued to affect immigrants from non-European countries even after the Canadian government eliminated racist immigration policies in 1962. Racism also affects how segments of Canadian society have perceived people from the Middle East, South America, Asia, South East Asia, Africa, and the West Indies who have immigrated to Canada at various stages in Canadian history. Stereotypes and fear of the unfamiliar have influenced how immigrants are treated in Canadian society and subsequently how their needs have been addressed by settlement service providers over the past 140 years. Historically, settlement practitioners have been primarily from white, Christian backgrounds. However, the profile has changed over the last 30 to 40 years. More and more settlement practitioners now have cultural and ethnic backgrounds that better represent the cultures and ethnic backgrounds of the immigrants that they serve.

Milestone 2: Post-War Immigration Challenges

The next milestone covers an era of political strife in Europe that required Canada’s military support. After the Second World War, immigration increased significantly because of an influx of war brides. The large numbers of war brides that accompanied returning soldiers came through the famous Pier 21 port in Halifax.

| January 01, 1939 | After the war, when the soldiers came home to Canada through Pier 21, a tide of war brides returned with them. |

|---|---|

| January 01, 1945 | Labour demand for post-war economic recovery encouraged European immigration from the United Kingdom and Western Europe and eventually the rest of Europe as well. |

| January 01, 1946 | Four thousand Japanese Canadians, more than half of whom were Canadian citizens, were deported to Japan. |

| February 10, 1946 | War brides arrived from England. |

| October 23, 1956 | Hungarian refugees arrived in Vancouver. |

After the Second World War, the Canadian economy started to recover rapidly, and as a result, there was a great demand for labour. During this time, the government encouraged immigration from Europe, this time promoting immigration from the United Kingdom and Western Europe. At this time, the political climate in Eastern Europe created mistrust of communism by the West that became known as the Cold War, which essentially stopped open immigration from this region of Europe (Troper, 2021).

In post–World War II Canada, Japanese Canadians became the target of racism because of Canada’s support for America following the 1941 Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. The video below, Japanese deportations in Canada during WWII : Throwaway Citizens (1995) – The Fifth Estate, gives a personal insight into this difficult part of Japanese Canadian history. The documentary uses the term “ethnic cleansing” to describe this period of Canadian history.

Fifth Estate. (2017, August 25). Japanese deportations in Canada during WWII: Throwaway citizens (1995) – The Fifth Estate [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ggNYkFg6AjA

Internment Camps During World War I and World War II

World War II geopolitics brought the fight against communism, fascism, and Nazism into the Canadian social consciousness and affected two established Canadian ethnic groups—German and Italian Canadians. These two ethnic groups came from countries that were political enemies of Britain and its allies. This led to a deportation order under the War Measures Act. This Act took away the civil liberties of German and Italian Canadians and subjected them to deportation or imprisonment in one of 26 internment camps. Internment camps in Canada during World War II held 24,000 people, including 12,000 Japanese Canadians (Roy, 2020). Other Canadian ethnic groups who were interned were from other countries at war with Canada’s allies. Immigrants from the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires, as well as from Germany and Bulgaria (Roy, 2020) were required to register themselves with the Canadian government as “enemy aliens.” They were subsequently rounded up and sent to internment camps across Canada. The following video documents the stories of some individuals who were affected by these War Measures Act practices. This video is called The Surprising Story of Canada’s Enemy Aliens.

Storyhive. (2017, May 19). The surprising story of Canada’s enemy aliens [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UY4vTBQTpUA&t=20s

The following is a poem written in 1940 and translated from Italian that recounts the experience of Emilio Garlardo, who was in one of the 26 interment camps found throughout Canada. Emilio is writing from the camp in Petawa, Ontario (Columbus Centre, n.d., para. 1).

Emilio Galardo, internee, poem translated from Italian, 1940 |

Milestone 3: Canada’s Evolving Immigration Policy

| January 19, 1962 | The Canadian government eliminated racial discrimination in Canada’s immigration policy. Immigration Regulations, Order-in-Council PC 1962-86, 1962 |

|---|---|

| January 1, 1967 | The second wave of Japanese immigration began in 1967 because of the “points system.” |

| October 1, 1967 | Deputy Minister of Immigration Tom Kent established a points system, which assigned points in nine categories, to determine immigration eligibility. |

| 1967 | About 64,000 West Indians came to Canada. |

| January 01, 1971 | For the first time in Canadian history, most of those immigrating to Canada were of non-European ancestry. |

| Early 1970s | Latin American refugees and immigrants arrived. |

| 1973 | Chilean refugees came to Canada. |

| April 30, 1975 | By 1975, Canada had admitted more than 98,000 refugees from in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos. |

| January 1, 1978 | The admission of refugees was now part of Canadian immigration law and regulations. |

| January 1, 1980 | Southeast Asian refugees, particularly those from Vietnam, were often referred to as the “boat people.” |

| December 19, 1984 | Canada saw immigration from Hong Kong because of the Chinese-British Joint Declaration mandating the return of Hong Kong to China in 1997. |

| August 11, 1986 | Sri Lankan migrants were rescued off the coast of Newfoundland. |

| 1990s | African refugees came from Sudan during and after the civil war. |

| 1970s and 1991 | Eritrean refugees came to Canada during and after the war of independence in Eritrea. |

| 1981 to 1995 | Around 10,000 Afghans arrived as refugees and asylum seekers. |

| January 1, 1999 | Canada saw the arrival of 11,200 Kosovars, most of them airlifted during the Kosovo war. |

| June 22, 2006 | The federal government officially apologized for the Chinese head tax. |

| August 13, 2010 | Tamil refugees arrived in Victoria. |

| November 4, 2015 | Canada saw the arrival of 44,620 refugees from Syria. |

The next milestone in Canada’s immigration history is a welcome pivot of ideology influenced by a new era of social consciousness of the 1960s. Shannon Conway (2018) describes this in her journal article abstract, “From Britishness to Multiculturalism: Official Canadian Identity in the 1960s”:

“The 1960s was a tumultuous period that resulted in the reshaping of official Canadian identity from a predominately British-based identity to one that reflected Canada’s diversity. The change in constructions of official Canadian identity was due to pressures from an ongoing dialogue in Canadian society that reflected the larger geopolitical shifts taking place during the period. This dialogue helped shape the political discussion from one focused on maintaining an outdated national identity to one that was more representative of how many Canadians understood Canada to be. This change in political opinion accordingly transformed the official identity of the nation-state of Canada” (p. 9).

This “geopolitical shift” (Conway, 2018) influenced the Canadian government to implement a policy that eliminated racial discrimination in Canada’s immigration policy. This shift in political and social ideology led to the establishment of a point system. On October 1, 1967, Deputy Minister of Immigration Tom Kent established a system that determined eligibility by assigning points in nine categories. This system established a more fair and transparent set of criteria for immigration approval. The point system criteria gave points in categories related to education, profession, financial resources, family status, and English- or French-language proficiency. It eliminated bias based on race and religion.

|

Did you know? In 1967, Canada became the first country in the world to develop and implement a point system for immigration. |

For the first time in Canadian history, most immigrants accepted for entry into Canada were of non-European descent. The scope of immigration extended beyond the European landscape to include people who fit the point system criteria. Groups of non-European immigrants came from Asia, South Asia, Latin America, Africa, and the Caribbean (Whitaker, 1991).

The concept of multiculturalism grew out of the new social consciousness of that time. However, the high criteria standards excluded the unskilled labourers who had once been a priority when the country was building infrastructure and industry. The system was designed to assign higher points to applicants who had the education, training, and skills required by industries in demand. The White Paper on Immigration created in 1966 challenged

this systemic practice of restriction on immigration and offered recommendations for immigration regulations enacted in 1967.

Refugees and Asylum Policy

At the end of World War II, Canada accepted refugees who were displaced by the war. Displaced persons such as surviving Jewish people from Germany and Poland were encouraged to find refuge in Canada after the defeat of Germany and Italy. Refugees from war-torn countries such as Hungary (1956) and Czechoslovakia (1968) were invited on an ad hoc basis according to their individual circumstances. Eventually, a government refugee policy was established in 1976 to set guidelines for inviting refugees to Canada. These guidelines for accepting refugees were developed in response to humanitarian crises created by war or environmental disasters. The various waves of refugees are identified according to the timeline in the following chart:

| Early 1970s | Latin American refugees and immigrants arrived. |

|---|---|

| 1973 | Chilean refugees came to Canada. |

| April 30, 1975 | By 1975, Canada had admitted more than 98,000 refugees from in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos. |

| January 1, 1978 | Admission of refugees was now part of Canadian immigration law and regulations |

| January 1, 1980 | Southeast Asian refugees, particularly those from Vietnam, were often referred to as “boat people.” |

| December 19, 1984 | Canada saw immigration from Hong Kong because of the Chinese-British Joint Declaration mandating the return of Hong Kong to China in 1997. |

| August 11, 1986 | Sri Lankan migrants were rescued off the coast of Newfoundland. |

| 1990s | African refugees came from Sudan during and after the civil war. |

| 1970s and 1991 | Eritrean refugees came to Canada during and after the war of independence in Eritrea. |

| 1981 to 1995 | Around 10,000 Afghans arrived as refugees and asylum seekers. |

| January 1, 1999 | Canada saw the arrival of 11,200 Kosovars, most of them airlifted during the Kosovo war. |

| August 13, 2010 | Tamil refugees arrived in Victoria. |

| November 4, 2015 | Canada saw the arrival of 44,620 refugees from Syria. |

Image Credits (images are listed in order of appearance)

Timms, P. (190–). Asian loggers and steam donkey [Photograph]. Vancouver Public Library Historical Photograph Collections. VPL Accession Number: 78316. https://www.vpl.ca/historicalphotos

Hindus may not vote in Vancouver. (1907, April 18). Vancouver Daily Province. Vancouver, BC.

Timms, P. (190–). A group of Sikh sawmill workers for Northern Pacific Lumber Co. at Barnet pose for the camera [Photograph]. Vancouver Public Library Historical Photograph Collections. VPL Accession Number: 7641. https://www.vpl.ca/historicalphotos