The Advent of Modern Conservation

The ecological deterioration and decline in wildlife populations that occurred as a result of industrialization in the twentieth century presents a question: what happened to the early conservationists? Some authors have suggested that the initial flourish of interest in conservation at the turn of the twentieth century waned once societal attention shifted to economic growth in the 1920s (MacEachern 2003; MacDowell 2012). In reality, conservation efforts during this period did not diminish at all, they expanded and became institutionalized (Burnett 2003). However, they remained narrowly focused on species that were hunted or harvested; broader conservation concerns had yet to be meaningfully recognized.

Over the ensuing decades, we got more of everything—bureaucrats, game wardens, foresters, scientists, schools, and associations—greatly expanding management capacity. Our knowledge base also improved. By the 1930s, game management emerged as a distinct discipline and research was well underway into species distributions, population sizes, food and habitat requirements, predator-prey dynamics, disease, and many other topics. Silviculture likewise underwent substantial development and maturation.

As capacity increased and ecological knowledge accumulated, management efforts became increasingly sophisticated. The basic objective of sustainable use morphed into the concept of maximum sustained yield, which guided research and management efforts in wildlife and forestry for much of the century (Larkin 1977). Regulations to avoid overexploitation were fine-tuned, and steps were taken to increase the productivity and long-term sustainability of desired resources. Species with no direct utility were largely ignored, and those identified as having negative effects were often targeted for elimination.

The management of Wood Buffalo National Park during the first half of the twentieth century provides a window into the mindset of the time. The park was established in 1922 to support the recovery of bison. Initial management efforts simply involved a prohibition on hunting by local Indigenous communities and others. Once the herd began to recover, the park administration began a program of small-scale, seasonal bison hunts, in response to a request for bison meat from the local residential school (McCormack 1992).

From the early 1940s until well into the 1950s, wolves in the park were poisoned with strychnine and cyanide, and a wolf bounty was used to encourage trapping, all to increase the production of bison (Fuller and Novakowski 1955). In the early 1950s, infrastructure within the park was expanded, and the commercial slaughter of bison began in earnest, lasting until 1967. In total, several thousand buffalo were killed, along with an unknown number of wolves (McCormack 1992). Wood Buffalo National Park forests fared no better. Approximately 70% of the park’s riparian old-growth spruce was clearcut between 1951–1991, without concern for the species that depended on it (Timoney 1996).

The upshot is that modern concepts of biodiversity conservation did not arise through the progressive refinement of early twentieth-century conservation principles. Management capacity and knowledge certainly increased over the years, but the objectives of management remained wedded to a narrow, utilitarian view of conservation. For the most part, wildlife and forests were treated as commodities, even in parks, and progress was measured in terms of rising production.

To be fair, there were some individuals at the fringe who argued for a less utilitarian approach to resource management. They were unable to effect much change during their time, but they did help prepare the ground for the future. One of these individuals was Grey Owl, whose articles and books were popular in the 1930s (Loo 2006). Writing from a cabin in northern Saskatchewan, Grey Owl railed against the commodification of wildlife. He suggested that conservation was hampered by the view that nature was a basket of goods that could return an income if properly managed.

Another important figure was Aldo Leopold, considered to be the father of wildlife management. Leopold’s early career involved killing cougars, wolves, and bears in New Mexico. However, in his later years, he came to believe that these types of management activities were misguided. In his most influential work, the Sand County Almanac (1949), he outlined a biocentric approach for interacting with nature that he termed the “land ethic.” The non-consumptive values and holistic ecosystem-based management concepts he articulated presaged the future direction of conservation:

The land is one organism. … If the biota, in the course of aeons, has built something we like but do not understand, then who but a fool would discard seemingly useless parts? To keep every cog and wheel is the first precaution of intelligent tinkering. … The land ethic simply enlarges the boundaries of the community to include soils, waters, plants, and animals, or collectively: the land. A land ethic of course cannot prevent the alteration, management and use of these resources, but it does affirm their right to continued existence. (pp. 190, 239–240)

A notable Canadian figure of this period was Ian McTaggart-Cowan. He advanced a holistic approach to conservation through television, radio, writing, and lectures. Other individuals and groups promoted direct interaction with wildlife. Birdwatchers and field naturalist groups were in the forefront (e.g., establishing the Audubon Society of Canada in 1948). Low-level efforts to support species at risk of extinction also continued. These efforts expanded from their initial focus on overhunted game species to new species such as the whooping crane and trumpeter swan. At the international level, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) was established in 1948, with a primary focus on endangered species.

Origins of the Environmental Movement

Although Leopold and his compatriots influenced many people, they were too far ahead of their time to affect mainstream thinking. The real crucible of modern conservation was the environmental movement of the 1960s, which carried conservation along like a surfer on the crest of a wave.

The environmental movement arose as a collective response to the negative impacts that industrialization was having on the environment. But there is more to the story than simple cause and effect. Consider, for example, the Cuyahoga River which runs through Cleveland, Ohio. This river was so polluted with industrial waste that in 1969 it started on fire (Stradling and Stradling 2008). The fire attracted widespread media attention, including an article in Time magazine which reached millions of readers. It graphically illustrated just how bad the nation’s environmental problems had become and fuelled outrage and demands for action. It was followed, in 1972, by the US Clean Water Act.

The problem with this narrative, which suggests a direct relationship between environmental damage, public concern, and policy response, is that the Cuyahoga River had burned at least nine times before (Stradling and Stradling 2008). The 1969 fire was not even the worst. The picture used in the Time article was actually from a much more serious fire in 1952. If environmental degradation was the trigger for action, why then did it take until 1969 for the public to engage? The same disconnect exists for most of the other environmental issues that rose to prominence in the 1960s. Clearly, other factors were at play. And in the messy details lie the foundations of modern conservation.

The world did not suddenly fall apart in the 1960s. Instead, a tipping point was reached that led to a new way of looking at things. In short, we developed an environmental consciousness. The key players in the development of this new environmental awareness included researchers, the media, environmental groups, policymakers, the public … and the hippies.

Hippies are symbolic of the counter-culture revolution that took place in the 1960s. Their contribution was to question authority (Fig. 2.15). Such youthful rebellion was, of course, not new. But in this case, many of the issues being raised resonated with the broader public, including the deaths of young men in an unpopular war in Vietnam, the prospects of a nuclear Armageddon, and slow poisoning from environmental pollutants. Consequently, many began to reconsider the merits of the paternalistic system that controlled decision making.

The range of issues attracting attention quickly expanded and people from all walks of life became activists or supporters of change. It was a social awakening, and North American society was never the same afterward. In particular, elitist, closed-door decision making would no longer be accepted. Henceforth, the public would demand a say.

The development of environmental consciousness also involved a conceptual frame shift. Frames are mental constructs that shape the way we see the world (Lakoff 2004). They help us make sense of events and information by providing background context and default interpretations of cause and effect. They are also value-laden, which means that certain aspects of reality may be highlighted while others are marginalized or ignored (Reese 2001). Because they are mental constructs, frames can change over time, even if the underlying reality does not.

Prior to the 1960s, people did not think of the environment in the same way we do now. Most environmental deterioration occurred out of view, and relatively few individuals had any direct knowledge of what was happening. There were no government monitoring programs, no environmental reporters, no activist groups, and little scientific research on environmental problems. Incidents like the early Cuyahoga River fires were reported as isolated local events rather than symptoms of a broader problem. The existing frame, to the extent that one existed at all, was that environmental damage was the cost of progress (Sachsman 1996).

The initial change in perspective was led by individual scientists with a personal interest in the environment and by environmental activist groups, most of which were spawned by the broader counter-culture revolution. These individuals and groups gave voice to the environment, bringing firsthand accounts and analysis of what was happening to a public that was unable to witness the changes directly. The publication of Silent Spring in 1962, by Rachel Carson, was a seminal event. It drew attention to the effects that pesticides were having on birds and, more generally, to the powerful and often negative effects of humans on the natural world.

As the 1960s progressed, the media began to play a central role in facilitating the environmental dialog, linking information providers with the general public. Stories about the environment proliferated and journalists began to connect the dots, interpreting individual local events in the context of broader national-scale concerns. By the time the Cuyahoga River burned in 1969, it was a national story about industrial pollution out of control, not a minor article in the local paper about how much it would cost to repair the railway bridge.

The interactions between scientists, activist groups, the media, and the public were mutually reinforcing. Mass media sparked public interest, which produced more activists and stimulated more scientific research, resulting in more information for the media in a virtuous cycle. In addition, political figures began to understand that taking a stand against pollution and other forms of environmental degradation made for good public relations. Their pronouncements and actions helped to legitimize the issues. Environmental awareness rose quickly, and by the first Earth Day, in 1970, the transition to the modern framing of the environment was essentially complete.

Indigenous Influences

Indigenous perspectives on conservation first attracted public attention with the writings of Grey Owl, who gained a wide audience in the 1930s (Fig. 2.16). Grey Owl suggested that much could be learned from the way that Indigenous people interacted with nature (Loo 2006). Other writers, such as Henry Thoreau and John Muir, had presented conservationist ideas ahead of him, but Grey Owl was the first high-profile author to make a strong connection between conservation and Indigenous ways of life.

Although Grey Owl planted a seed, the time was not yet ripe for widespread uptake of Indigenous perspectives. This had to wait until the arrival of the environmental movement in the 1960s. In the search for alternative approaches, Indigenous worldviews re-emerged and found fertile ground.

The incorporation of Indigenous perspectives in this period centred on broad philosophical themes about stewardship and respect for nature that resonated with an increasingly environmentally aware public. These ideas were widely circulated, sometimes ending up on posters alongside Indigenous people and art (Fig. 2.17). Common themes included respect and reverence for wildlife and nature, the idea that resources are being held in trust for future generations, and the intrinsic interconnectedness and sacredness of animals, humans, and the land. Popularized quotes from a speech given by Chief Seattle in 1854 provide an example of how these ideas were presented:

We know that the white man does not understand our ways. One portion of the land is the same to him as the next, for he is a stranger who comes in the night and takes from the land whatever he needs. The earth is not his brother, but his enemy—and when he has conquered it, he moves on.

Humankind has not woven the web of life. We are but one thread within it. Whatever we do to the web, we do to ourselves. All things are bound together. All things connect.

Humans merely share the earth. We can only protect the land, not own it.

A defining feature of this period was that Indigenous worldviews were being interpreted and presented mainly by non-Indigenous commentators. Ironically, Indigenous people were themselves still marginalized at the time (e.g., the right to vote was not awarded until 1960). It was the harmony-with-nature ideal that Indigenous people represented, and the powerful symbolism they provided, that was most important to non-Indigenous conservationists. To some extent, this involved filtering, simplifying, and romanticizing Indigenous culture and worldviews.

There was also liberal use of artistic licence concerning attribution. For example, although Chief Seattle did give a speech in 1854, his popularized quotes were later attributed to a television scriptwriter named Ted Perry (Stekel 1995). And while Grey Owl did live with and learn from Indigenous people, he was later exposed as an Englishman. Despite the dubious morality of some of these tactics, their historical impact is clear. Indigenous perspectives on nature went from relative obscurity into the mainstream, affecting the thinking of Canadians at large and helping influence the changes in resource management that occurred during this period.

Later in the twentieth century, Indigenous communities found their own voice and began to engage directly in public discourse about resource use, especially at the local level (see Chapter 3). Moreover, conservation was often subsumed into broader discussions about treaty rights, self-determination, and control over resources.

An important feature of this later period was the development of place-based conservation campaigns involving formal alliances between Indigenous communities and conservation groups. Notable examples include campaigns against logging in Clayoquot Sound in British Columbia (Nuu-chah-nulth, 1993), Alberta’s boreal forest (Lubicon Cree, 1990), and the Temagami forest in Ontario (Teme-Augama Anishnabai, 1989). The objectives of conservationists and Indigenous communities aligned in the context of these campaigns and this provided the foundation for widespread gains in wilderness protection.

From Game to Biodiversity

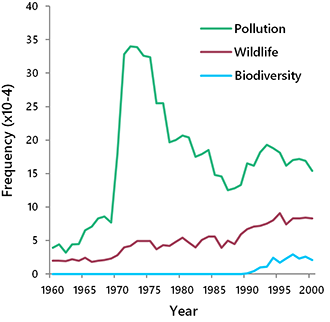

Although the primary concern of the early environmental movement was pollution, the plight of wildlife also received increased attention at this time (Fig. 2.18; Gregg and Posner 1990). The scope of concern expanded beyond overexploitation to include habitat degradation and the harm to wildlife arising from pesticides and pollutants. Public attitudes toward wildlife also changed, with increasing emphasis placed on non-consumptive values, the moral right of all species to exist, and general respect for nature.

Narrow utilitarian perspectives were faulted for failing to prevent the environmental declines that had occurred in preceding decades. From this point forward, resource management would be increasingly scrutinized and contentious, involving competing and conflicting values held by different segments of society. Utilitarian values continued to play an important role in decision making but they were no longer the default.

The changing status of the wolf is illustrative of the public’s evolving attitudes toward wildlife. Prior to the 1960s, wolves were considered dangerous and undesirable, a menace to human safety and livelihood. Extermination campaigns, such as those in Wood Buffalo National Park, were routinely conducted, and public opposition was basically nonexistent. In the 1960s, through writers such as Farley Mowat and filmmakers like Bill Mason, the public—especially the urban public—began to see wolves in a new light. In Mowat’s Never Cry Wolf, released in 1963, wolves were noble creatures whose commendable conduct highlighted the virtues of nature (Loo 2006). Mowat may have made liberal use of literary licence, but his story resonated with millions of readers. Mason was later hired by the Canadian Wildlife Service to provide some balance to Mowat’s writing, but his 1972 documentary film, Cry of the Wild, further advanced the preservationist perspective.

Never Cry Wolf and Cry of the Wild were not just arguments against predator control; they embodied a new conception of wildlife and conservation (Loo 2006). Rather than efficient use, they advocated an ethic of existence, similar to what had been proposed earlier by Leopold. However, rather than emphasizing ecological integrity, their arguments were based on the intrinsic value and rights of animals. These views may have found little support among farmers and hunters, but had great appeal to city dwellers, who sided with the wolves. For these people, utilitarian and scientific arguments were not critical factors. They were swayed by the ethical dimensions of the issues, viewed in the broader context of social change and progressive loss of wilderness. For many, saving the wolf was a proxy for saving the wild.

The shift in public attitudes toward wildlife led to a series of policy changes. The US was again first to respond. However, this time Canada did not simply follow the US lead. Our response was substantially slower and differed in several important aspects that set us on a distinctly different policy trajectory (VanNijnatten 1999).

In the US, the landmark change was the passage of the US Endangered Species Act, in 1973. This Act was heavily influenced by input from scientists in the Bureau of Sport Fish and Wildlife and members of the conservation community (Illical and Harrison 2007). Through their efforts, the Act included a broad definition of species, a scientifically based determination of endangerment, and mandatory prohibitions on harm to listed species.

Notably lacking in the Act were economic considerations, reflecting the virtual absence of input or opposition from the private sector (Illical and Harrison 2007). In hindsight, many of the Act’s provisions should have been red flags for the business and agricultural communities. However, lacking experience with such legislation, the private sector did not grasp the full import of the new Act as it related to their interests. In the absence of arguments to the contrary, the bill received near unanimous consent in the House and Senate.

A key feature of the US Endangered Species Act is the use of non-discretionary language, which reflects the separation of powers within the US system of government. Congress tends to be distrustful of the Executive Branch, which it must rely on to execute its instructions. Therefore, US environmental statutes have invariably employed non-discretionary language and firm deadlines to control the actions of administrative agencies, backed for good measure by “citizen suit” provisions that invite any individual to sue the executive should it fail to fulfill Congressional mandates (VanNijnatten 1999). The US system also contains many veto points which make it difficult to unwind laws once they are passed.

Once the practical implications of the Endangered Species Act began to be understood, developers sought to avoid them. This led to legal action, culminating in a Supreme Court challenge over the construction of a dam that posed a threat to a small endangered fish—the snail darter. The Supreme Court ruled that, despite the obscurity of the snail darter, the intent of the law was quite clear and non-discretionary: all species were to be protected, regardless of the cost. Amendments to the law were made in subsequent years, providing exceptions; however, there has never been enough support for the fundamental features of the Act to be repealed (Illical and Harrison 2007).

The trajectory of wildlife policy in Canada has been quite different from that of the US, for a variety of reasons (VanNijnatten 1999; Illical and Harrison 2007). In Canada, the legislative and executive branches of government are combined, so there is no incentive for creating non-discretionary laws. Our environmental statutes typically authorize, but do not compel, government actions. Second, because of decisions made at the time of Confederation, provinces have primary jurisdiction over natural resources, including wildlife. This has led to the uneven development of wildlife policy across the country and has hindered the coordination of conservation efforts. Finally, because Canada did not react as quickly as the US to the initial wave of environmentalism, there was an opportunity to learn from the US experience. The most important lessons were gleaned by the business community who, in contrast to their American counterparts, mounted a strong lobby to limit the scope and economic impact of Canadian wildlife legislation as it was being developed.

Initial efforts to update Canadian wildlife policies began in the mid-1960s, with efforts by the Canadian Wildlife Service, in cooperation with the provinces, to develop a national policy on wildlife. These efforts culminated in the passage of the Canada Wildlife Act in 1973—the same year as the US Endangered Species Act. The new Act expanded the definition of wildlife to include any non-domestic animal and also stated that any provisions respecting wildlife extended to wildlife habitat. The Act also included a provision for the protection of species at risk of extinction, expanding the scope of federal interest in wildlife beyond its traditional bounds. In contrast to the US law, there was no explanation of what the species recovery measures might entail, who would do them, or when they would be implemented. Instead, our Act simply stated, “The Minister may … take such measures as the Minister deems necessary for the protection of any species of wildlife in danger of extinction” (GOC 2015, Sec. 8).

Although a number of conservation groups and some members of Parliament were pressing for federal endangered species legislation, it was evident to Canadian Wildlife Service officials that such an approach would be anathema to the provinces (Burnett 2003). Therefore, national efforts were instead focused on a program to determine species status, without infringing on the legal prerogative of each province to manage wildlife within its boundaries. This led to the establishment of the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) in 1977.

During the 1980s, wildlife policy continued to evolve through regular conferences of federal and provincial wildlife ministers. One notable change was a further broadening of the definition of wildlife to include all wild organisms, including plants and invertebrates. In 1988, Canada’s wildlife ministers established the Recovery of Nationally Endangered Wildlife committee to coordinate the development and implementation of recovery plans for the growing list of species that were being listed by COSEWIC. The committee was also intended to prevent species from becoming threatened or endangered and to raise public awareness of species conservation.

In the late 1980s, Canadians went “green,” amid a renewed surge in global environmentalism. Polling in 1990 found that 82% of Canadians agreed with the statement “We must protect the environment even if it means increased government spending and higher taxes” (Lance et al. 2005). Also, Canadian Wildlife Service surveys demonstrated that wildlife-related activities, especially non-consumptive ones such as photography and birdwatching, were growing rapidly (Burnett 2003). Federal interest in conservation reached its high-water mark at this time. In 1990, the federal Progressive Conservatives unveiled their Green Plan, which provided funding for a range of environmental initiatives, including wildlife conservation. Canada was also an active participant in the development of the 1992 UN Convention on Biological Diversity, and we became the first industrialized country to ratify it. This was followed, in 1995, by the Canadian Biodiversity Strategy (EC 1995).

The Canadian Biodiversity Strategy marked the final stage in the conceptual evolution of conservation in Canada. In contrast to previous conservation policies, wildlife was now mentioned only in passing. The primary focus had shifted to biodiversity, a term that had only come into widespread use a few years earlier (Fig. 2.19). The Strategy defined biodiversity as “the variety of species and ecosystems on earth and the ecological processes of which they are a part” (EC 1995, p. 5). This was an important conceptual shift. Conservation was now about maintaining biodiversity, not the wise use of a few preferred species.

In the mid-1990s, efforts also finally got underway to develop federal species at risk legislation. In contrast to the 1973 US Endangered Species Act, which passed swiftly with minimal opposition, the development of Canada’s Species at Risk Act (SARA) was highly contentious. Conservation groups were guided by the US experience and sought comparable mandatory provisions for endangered species in Canada. However, business interests, also guided by the US experience, mounted a vigorous opposition. Further complicating the negotiations was the reluctance of the provinces to accede any further control over wildlife management to the federal government.

Given the widely divergent positions of conservation groups and scientists on one side of the debate, and the provinces and business interests on the other, it took until 2002 for SARA to finally be passed. The federal government sought a middle ground, and this meant that many compromises were made. SARA ended up substantially weaker than its US counterpart. We will examine the specific strengths and weaknesses of SARA in Chapter 6.

While SARA was being developed at the federal level, many of the provinces adopted endangered species legislation of their own. By the time SARA was passed in 2002, eight provinces and territories had species at risk legislation in place, and five did not (Boyd 2003). The provincial legislation was generally weaker than SARA and featured the same compromises (see Chapter 3).