Environmentalists

Who are the Environmentalists?

To those who oppose their views, environmentalists are often characterized as “special interests,” somehow distinct from the rest of society. This simplistic characterization is at odds with what we know about public perspectives. Conservation worldviews exist along a continuum, and environmentalists are simply individuals drawn from the biocentric end of this spectrum (McFarlane and Boxall 2000b; McFarlane and Boxall 2003). There is no distinct “us” and “them.”

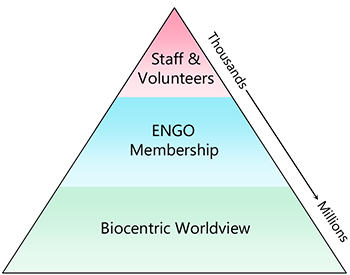

Environmentalists are themselves a heterogeneous group. The main differentiating factor is the level of engagement. Those on the cusp of environmentalism might come out to a nature-related event, donate some money, or sign a petition if asked. They may also make purchasing decisions based on their perception of environmental impact (CCRM 2014). Such individuals number in the millions in Canada.

The next level of engagement is typically membership in an environmental non-government organization (ENGO). These individuals gain greater awareness about issues through group newsletters and websites, and they support the aims of their organizations by providing funding and perhaps soft advocacy such as letter writing. Further engagement often involves volunteering. Some ENGOs depend on volunteers to help implement programs that are planned and organized by staff. Many smaller groups are entirely run by volunteers.

The highest level of engagement involves serving on the board of an ENGO or working as paid staff. Outside of Ducks Unlimited Canada and the land trusts, which have relatively large staffs, the full-time paid staff of conservation-oriented ENGOs in Canada is a small select group, collectively numbering in the hundreds (Grandy 2013). These are highly dedicated individuals, and for most of them, working for a conservation organization is as much a mission as it is a job.

Increased engagement is accompanied by increased knowledge about conservation issues and often involves a hardening of opinions concerning resource development (McFarlane and Boxall 2003). A new volunteer representing a local group at a decision-making forum may only be able to speak in terms of basic value sets. More experienced volunteers may have acquired considerable knowledge on issues they have worked on for many years. Paid staff are likely to have formal training in ecology, law, or management and will typically have a depth of technical expertise on issues under discussion that matches or exceeds that of government representatives and other stakeholders. This expertise is gained within the context of a strong biocentric worldview and will therefore be subject to certain filters. An environmentalist and a forester may both agree on the need for sustainability but hold completely different perspectives on what that looks like in practice.

From this description, it is apparent that the environmental community has a pyramidal structure (Fig. 3.2). A potential concern with this organizational structure is that decisions concerning objectives, tactics, and the allocation of effort are usually made by a small number of people, including paid staff and active board members (Brulle and Jenkins 2010). Critics have argued that because of this disconnect between group leaders and the organization’s membership, ENGOs really are a special interest after all.

What these critical views fail to consider is that membership and support of ENGOs is a voluntary process and there are many groups to choose from. If a group is ineffective or chooses to pursue a narrow or unpopular agenda, members vote with their feet, taking their support with them. This process ensures that ENGOs and their leaders remain aligned with the interests of their members. Without a strong membership, groups lose their core funding and, just as important, the political power that comes with representing the public interest.

Another potential concern is that many ENGOs receive a substantial proportion of their funding from large philanthropic foundations and the government (Tedesco 2015). Because of this, critics have charged that environmental groups may be more attuned to the interests of external funders—another special interest—than their members (Krause 2013).

Foundation and government funding certainly comes with strings attached; however, the relationship is not coercive. ENGOs seek external funding to execute programs they have developed on the basis of carefully crafted strategic plans. Strategic plans are in turn a reflection of a group’s mission and vision, which define what it stands for, what it does, and where it fits in the broader ENGO ecosystem. A group’s mission and reputation will not readily be jeopardized for individual funders, which come and go over the years. Nevertheless, external funding does change the opportunity landscape and can thereby influence which projects advance and which remain on hold.

Foundations are best characterized as investors seeking the highest rate of return. Smaller conservation groups working on local issues receive some attention, and the occasional long-shot is entertained. But the bulk of the funding is directed to programs likely to have a broad impact and to organizations with the size and technical expertise needed to make significant progress (Brulle and Jenkins 2010).

In summary, much goes on behind the scenes that determines what individual ENGOs do, and membership is rarely involved in making these decisions. In this respect, ENGOs are no different from most large member-based organizations and elected governments. ENGO members express their support by renewing their membership each year and providing ongoing financial support. This base of support is very broad in Canada. According to the 2012 Canadian Nature Survey, 4.8 million Canadians annually donate money to nature conservation organizations (CCRM 2014). Active membership in these organizations is collectively in the hundreds of thousands (Grandy 2013).

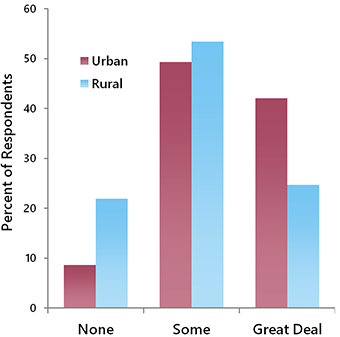

Support for ENGOs is also reflected in public opinion about who should be allowed to influence decision making related to resource management. The groups that typically receive the highest support are scientists, ENGOs, and local communities (Robson et al. 2000; Parkins et al. 2001; McFarlane et al. 2007). Support for ENGO inclusion is highest among urban dwellers, but even among rural residents, support is still substantial (Fig. 3.3).

The ENGO Ecosystem

Individual environmentalists are typically concerned about a wide range of issues, from biodiversity to pollution to global warming. Environmental groups, however, tend to specialize. In the following overview, we will explore the diversity that exists, focusing on groups that are active in biodiversity conservation to at least some degree.

The vast majority of conservation-oriented ENGOs are small volunteer-run organizations that work on local or regional issues (Hall et al. 2005). These include stewardship groups, watershed councils, naturalist clubs, and a host of “friends of …” societies. There are also many organizations that form in opposition to proposed developments. These groups are generally composed of local citizens that share an interest in some aspect of conservation and have joined together to do what they can to help. Collectively, these groups make a substantial contribution to conservation by raising awareness of local issues and influencing resource management at the local level. These are also the groups that regional and provincial-level planners turn to for obtaining local perspectives on land use.

On the other end of the spectrum are the large provincial and national conservation organizations. Though few in number, these groups have the largest memberships and receive most of the available funding (Hall et al. 2005). Because of regional overlap, these large ENGOs must compete for members, funding, and attention to their ideas. Consequently, they have differentiated to fill specific niches (Table 3.2). Some are confrontational; others are cooperative. Some are generalists, and others are specialists. Some are grassroots organizations with regional chapters, whereas others are run more like centralized corporations. At the most fundamental level, the groups can be divided into those that primarily conduct hands-on conservation and those that operate mainly in the public sphere, conveying information and ideas.

Table 3.2. Overview of national ENGOs that engage in conservation activities in Canada, ranked by annual revenue.1

| Organization | Revenue (millions) |

Staff2 | Origin | Focus |

| Nature Conservancy of Canada3 | 185.2 | 514 | 1962 | Land trust |

| Ducks Unlimited Canada3 | 104.6 | 486 | 1938 | Wetland protection |

| Greenpeace3 | 47.6 | 1971 | Multi-faceted | |

| Canadian Wildlife Federation | 33 | 65 | 1962 | Wildlife conservation |

| World Wildlife Fund Canada3 | 30.7 | 110 | 1967 | Wildlife conservation |

| David Suzuki Foundation | 14.7 | 83 | 1990 | Multi-faceted |

| Canadian Parks & Wilderness | 11.7 | 92 | 1963 | Wilderness preservation |

| Birds Canada | 8.8 | 119 | 1967 | Wildlife research |

| Ecojustice | 8.3 | 74 | 1990 | Environmental law |

| Nature Canada | 6.9 | 56 | 1939 | Naturalist clubs |

| Wildlife Conservation Society3 | 6.5 | 52 | 2004 | Wildlife research |

| Environmental Defence | 4.5 | 54 | 1984 | Multi-faceted |

| Stand.earth3 | 3.7 | 2000 | Multi-faceted | |

| Wilderness Committee | 3.3 | 26 | 1980 | Wilderness preservation |

| Wildlife Preservation Canada | 1.4 | 44 | 1985 | Wildlife conservation |

| Trout Unlimited | 1.3 | 16 | 1972 | Stream protection |

| Sierra Club Canada (national) | 1.2 | 59 | 1969 | Multi-faceted |

1Data obtained from Canada Revenue Agency charity listings, downloaded Jan. 2023 from https://www.canada.ca/en/services/taxes/charities.html?request_locale=en.

2Staff includes both full- and part-time employees.

3For international groups, the information provided here refers to Canadian operations only.

The groups that engage in hands-on conservation rarely generate news headlines, but they account for the lion’s share of Canadian conservation staff and expenditures (Table 3.2). Most of these groups are focused on habitat preservation and restoration, as exemplified by Ducks Unlimited Canada, the Nature Conservancy of Canada, and other land trusts. They work cooperatively with government and industry and derive a large portion of their funding from these sources.

These groups protect land mainly through partnerships with private landowners in agricultural regions. The priorities for protection are identified in strategic plans that reflect conservation need, opportunity, and the group’s main interests (e.g., wetlands). Once willing partners within priority areas are identified, lands are secured using three main approaches: land donations, land purchases, and conservation easements (see Chapter 8). These groups also promote conservation through their government and industry relationships and they often participate in government planning initiatives.

In addition to securing land for protection, some of these groups engage in ecological restoration. For example, they may re-establish natural vegetation on cultivated lands or restore the hydrological integrity of degraded wetlands (Fig. 3.4). Land trusts usually focus their restoration efforts on land parcels that they have protected; however, Ducks Unlimited conducts its wetland restoration projects on a much broader scale.

The other ENGOs—those that do not engage in hands-on conservation—operate in the public sphere, rather than with individual landowners. One of several methods they use to advance conservation is public education. Education raises the profile of biodiversity among the public and helps individuals maintain a connection to nature and its values. ENGOs organize nature walks, give public presentations, generate media stories, and prepare educational materials for use in schools among other activities.

ENGOs also serve in a watchdog role, providing eyes and ears for the public on issues related to conservation. ENGOs have extensive networks that connect them with what is happening on the land. They also draw heavily on research from the scientific community, with which they have a symbiotic relationship (see Chapter 4). Through this process, existing and emergent threats to biodiversity are identified, and priorities for action are brought to the public’s attention. In addition, ENGOs cast light into shadowy areas of policy, exposing the full costs and risks of development and forcing governments to defend their decisions. They also hold governments and industry to account when policies and regulations are not implemented or properly enforced.

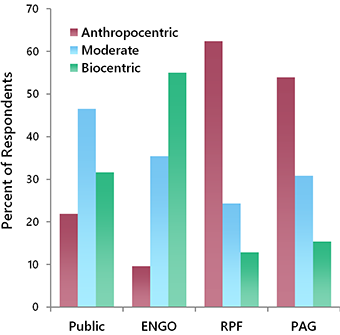

Lastly, ENGOs serve as advocates, providing a voice for nature and the conservation-minded public in decision-making forums. ENGOs also introduce new ideas into the public discourse and promote solutions to conservation problems in the form of alternative management approaches. These are critical functions because no other stakeholders effectively represent the biocentric views of Canadian society. For example, industry advisory groups tend to have more of an anthropocentric worldview (Fig. 3.5). So do resource professionals.

Advocacy can take many forms. It can be reactive, such as responding to proposed projects, policies, and legislation (Fig. 3.6). It can also involve proactive lobbying of politicians and government bureaucrats in support of ENGO programs and campaigns. Such lobbying has historically been highly constrained by tax laws, but these restrictions were loosened in 2018. Much advocacy also gets done through the creative use of educational materials and the support of volunteers. Finally, advocacy efforts are sometimes aimed directly at resource companies, using both carrot and stick approaches (discussed below).

Setting Priorities

Conservation-oriented ENGOs share a common interest in maintaining biodiversity. However, individual groups lack the capacity to address this goal in its entirety, so they concentrate their efforts on specific issues. In so doing, the groups play a major role in setting the conservation agenda within the entire public sphere.

Priority setting by conservation groups typically begins with a regional assessment of threats, often with an emphasis on human activities that disturb habitat. The level of threat is presumed to increase with the intensity of disturbance and its extent. Scientific information also feeds into the process. Reports about the effects of different types of human activities on ecological systems and species at risk are of particular interest.

The determination of conservation priorities also includes an assessment of opportunities, barriers, and the overall likelihood of a project’s success (Brulle and Jenkins 2010; Dart 2010). Given limited capacity, conservation groups need to focus their activities where they will do the most good. But this determination is far from easy given the basic paradox of conservation: protection is easiest to achieve where it is least needed. Groups must often choose between projects that address a critical conservation need, but come with high barriers to success, and projects of lower importance that are more achievable. Such determinations are all the more difficult because the likelihood of success is difficult to predict.

The main factors that ENGOs consider when judging the likelihood of success include:

- Political opportunities and barriers. Political receptivity to conservation waxes and wanes over time. Therefore, prioritization often includes an element of opportunism, as ENGOs make the most of opportunities that occasionally present themselves on specific issues. Conversely, conservation issues that face strong political opposition may be assigned a lower priority.

- Public support. ENGOs derive political influence from their claim to represent the biocentric views held by a broad segment of society. The more evidence there exists of this linkage, the more influence they have. This means that ENGOs must carefully consider projects in terms of their public appeal. All else being equal, it is much easier to generate broad public support for the protection of a majestic old-growth forest or a charismatic mammal than it is for a mosquito-infested peat bog or an endangered lichen. Despite ENGO aspirations of conserving biodiversity as a whole, such realities cannot be ignored.

- Allies. Profile, capacity, and influence in political decision making can be strengthened through alliances with other stakeholders. Therefore, effort may be channelled into projects that align with the interests of other organizations, such as other ENGOs, Indigenous communities, progressive resource companies, and funding foundations. Collaboration with other ENGOs works best when the groups involved have complementary approaches, but tends to be avoided when there is a potential for redundancy. For example, confrontational groups may use high-profile campaigns to raise awareness of issues, creating space for local policy-oriented groups to advance specific solutions.

- Opposing values. An important determinant of success is the degree of conflict with competing values. Species and ecosystems with the poor fortune of existing in areas of high resource value are difficult to protect. A modifying factor is the extent to which solutions exist for reducing or eliminating the main points of conflict, allowing for win-win outcomes.

- Strategic value. Though the likelihood of success in the short term is an important consideration, projects may also be undertaken for their strategic value in advancing conservation over longer timeframes. Favourable political environments do not arise spontaneously. They are usually the result of long-term efforts that may offer little apparent success in their early stages.

Priority is influenced not only by the likelihood of success but by the ability to measure success (Grandy 2013). This is one reason why habitat protection efforts tend to be favoured: the outcomes are clear and robust. Protected areas established through conservation campaigns in the twentieth century continue to protect habitat today. The same goes for private land that was purchased or deeded for the purpose of conservation. There is very little ambiguity about what was achieved or who achieved it.

Measuring success is much more challenging for projects related to conservation policies and practices. In the policy realm, many players are involved, and everything is interconnected, so it is difficult to have a decisive effect. And when change does occur, it is hard to know who was responsible for what. Moreover, experience has also shown that success in this area is often illusory. Hard-won policies may fail to be implemented, and commitments may be repealed with a change in government.

Lastly, priorities are influenced by institutional factors, such as a group’s primary mission, technical expertise, and contact networks. Spatial scope also plays a role. Provincial and regional groups often engage in local issues that national groups overlook or choose to avoid because better prospects can be found elsewhere.

In summary, the projects that ENGOs undertake, and by extension, the conservation issues that reach the public consciousness, are not simply a reflection of conservation need. ENGOs usually approach conservation from a highly practical perspective, blending ecological science and social factors when setting priorities. The process is messy and subject to various shortcomings, but it reveals important conservation realities. Conservation strategies and plans have no value if they are incapable of effecting change. There is a need for plans that offer solutions that are workable in a world of competing values and that resonate with the broad public. In Chapter 4, we will see that conservation practitioners working in scientific and management capacities face very similar challenges.