Industry

Resource development is associated with utilitarian values and has several distinct forms of support. The resource industry is a provider of necessary goods and an important contributor to employment and the general health of the economy. This generates support across a broad swath of society, including individuals with a moderately biocentric worldview. Such support is generally accompanied by an expectation of sound environmental management.

Another form of support resides in rural communities that rely on resource companies for employment, tax revenue, and opportunities for local businesses. Support is typically highest among company staff; however, working for a company does not translate into unconditional support for what the company does. Individuals may work for a company simply because it offers a high wage or because few alternatives for employment exist in small communities.

A third group of supporters, and arguably the most important from a company’s perspective, are shareholders. Resource companies may be valued by the public for the raw materials, jobs, and taxes they provide, but this is not why they exist. Companies are business enterprises that exist to generate a financial return on capital provided by their owners. This distinction is important because the underlying profit motive directs and constrains company decision making. Company directors have a fiduciary duty to their shareholders to use the company’s assets efficiently and effectively, which in practice means optimizing production and minimizing costs. Biodiversity conservation generally enters this equation as a cost, so decisions supporting protection measures must be justified by a business case, such as risk management related to social licence (discussed below).

In land-use decision making, resource companies no longer enjoy a monopoly on government attention, but they still retain important structural advantages (Wood et al. 2010). In many cases, they are the only stakeholder that contributes significantly to the local and regional economy. This affords them considerable influence with government decision makers, who are responsible for both land management and fiscal management. Governments must also honour the rights that companies have been awarded under tenure and licence agreements. The alignment of resource companies with the interests of local communities further boosts their influence. Finally, resource companies have a high level of government access through personal networks that are built, in part, on the reciprocal flow of staff between government and industry (Meghani and Kuzma 2011). Through these processes, industry is able to exert considerable concentrated political power at the local level, whereas the power of ENGOs is mostly urban based and less focused.

Industry and the Environment

Approvals for industrial projects normally come with environmental constraints. Companies must also respect the laws and policies of the jurisdiction in which they operate. Although companies are occasionally caught breaking the rules, they generally accept the imposed environmental constraints as one of the costs of doing business.

A challenge companies face is that environmental constraints are not fixed. Sometimes new information comes to light, such as better understanding of the ecological effects of an industrial practice. Or it may be that long-term cumulative impacts have pushed a local ecosystem or species to a critical state. In many cases, the impetus for change comes from evolving social concerns and priorities. As we saw in Chapter 2, public values and environmental awareness underwent a seismic shift in the late twentieth century, leading to demands for higher standards of environmental protection. Canada’s resource sector responded with broad commitments to environmental sustainability (Fig. 3.7; Hilson and Murck 2000; Lazar 2003).

Environmental sustainability has implied tests and standards that often exceed government regulations. This extra-governmental standard has been called the “social licence to operate,” and presents an ongoing vulnerability (Boutilier 2014). Industry has done much in recent years to improve its practices and can point to many success stories, but the undeniable reality is that Canada’s biodiversity is in a worse state today than when the resource industry’s commitments to sustainability were made (CCRM 2010; EC 2012a). In the context of sustainability, doing better is not the same as doing enough.

One approach companies use to reduce their environmental risk profile is continuous improvement of their practices. In some cases, innovative solutions can be found that support biodiversity without being disruptive or costly to implement. For example, in forested areas, seismic exploration for oil and gas used to require 6–8 m-wide linear corridors created by bulldozers, and a large proportion of these lines failed to regenerate in subsequent decades (Lee and Boutin 2006). Today, equipment is available for conducting seismic exploration on lines that are only 2.5 m wide, and the cost of the new equipment is offset by reduced penalties for timber damage.

In most cases, new conservation measures impact company profits to some degree. A natural tendency is for companies to implement the least costly practices first and to delay or avoid implementing more costly practices. For example, in the forestry sector, efforts to maintain natural forest structure have focused on varying the size and shape of harvest blocks. Some cost is involved because planning is more complicated and staff must be retrained, but these costs are manageable. Other, more costly measures, such as retaining old-growth forest, have typically been resisted (see Chapter 7).

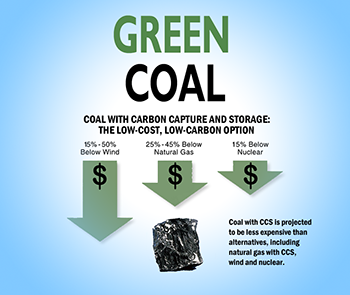

Companies also reduce their environmental risk profile through public outreach. Their aim is to convince people that their operations are ecologically sustainable and further protection measures are unnecessary (Fig. 3.8). In this, companies have several factors operating in their favour. Their efforts over the years to improve practices legitimately bolster their claim of sustainability. This is a message that resonates well with a large segment of the public because people would like to believe that their use of natural resources is not contributing to the deterioration of the environment. Less constructively, companies may use obfuscation as a tool for masking problematic issues. The complexity of conservation issues makes this an effective tactic (Jacques et al. 2008). Finally, resource companies have operating budgets that can support large, sustained public relations efforts that reach a wide audience. Money is also often used to buy goodwill; for example, by funding the purchase of land for conservation and by supporting local community initiatives.

Working against the resource companies is a low level of public trust (Fig. 3.1). In an international survey, the four industrial sectors with the lowest trust ratings were mining, chemical, oil, and tobacco (Boutilier 2014). Mistrust arises from periodic high-profile disasters that undermine industry claims of reliable management, such as the catastrophic tailings pond failure at the Mount Polley mine in BC in 2014 (GOBC 2014). Trust is further eroded by the all-too-common exposure of fraudulent claims. If a highly reputable company like Volkswagen is willing to manipulate their emissions data in a multi-billion-dollar gamble to improve sales (Neil 2015), it makes people wonder what other companies may be hiding.

The other major challenge industry has in defending its environmental claims comes from ENGOs. In contrast to the public, ENGOs have the technical capacity to sort truth from fiction when it comes to claims about sustainability. Thus, industry efforts to simply relabel old practices with new terminology are usually unmasked. ENGOs do not have the budgets to match industry’s public relations efforts, but they do enjoy a high level of public trust, which works in their favour. For its part, industry is often able to successfully counter ENGO demands for change with arguments based on scientific uncertainty and the need for more research. In some cases, additional study is indeed the most appropriate course of action. But all too often, protracted debate and concerns about uncertainty are used simply as tactics to delay action (Aklin and Urpelainen 2014).

Market Forces

The extent to which companies will implement progressive environmental practices, in excess of legal requirements, boils down to a business decision. In some cases, the logic is to avoid having even more restrictive regulations imposed by governments seeking to address unresolved environmental concerns. In many other cases, the costs and benefits of progressive practices are framed in terms of market access, which is another way of expressing social licence. According to the Canadian Nature Survey (CCRM 2014, p. 1), 57% of Canadians purchase “products and services that are more environmentally friendly than their competitors.” For companies, the potential gains and losses associated with such purchasing decisions must be weighed against the costs involved in raising the bar of sustainability.

In practice, the linkage between consumers and resource companies is highly convoluted. Consumers generally do not buy raw materials like crude oil and copper ore; they buy manufactured goods like gasoline and extension cords. Therefore, to establish a business case for conservation, there must be a way of tracking the supply chain, so that customers can identify end products made from sustainably derived raw materials. Also, claims concerning sustainability must be substantiated through an objective and impartial assessment of operating practices against meaningful standards. Without this step, companies that implement progressive practices cannot differentiate themselves from competitors that pay only lip service to sustainability. Established standards also help protect consumers from being misled.

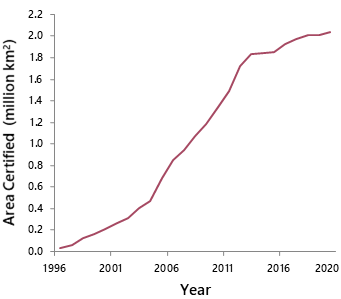

Tracking the chain of custody is very difficult within the oil and gas and mining sectors, with the notable exception of diamonds. Therefore, the most progress in product certification and tracking has occurred in the forestry sector. Forest certification was pioneered by the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) in the 1990s, and to date, more than 2 million km2 of forest have been certified under this system, in 86 countries (Fig. 3.9). In Canada, 22% of managed forests are now FSC certified (FSC 2020).

The way FSC certification works is that companies request (and pay for) an audit of their operations by an accredited certifier. To gain certification, companies must meet FSC’s environmental and social standards, developed by a group of ENGOs, retailers, unions, and Indigenous peoples (FSC 2020). FSC also runs a chain-of-custody system that tracks fibre from certified forests through the supply chain all the way to the customer. Thus, the overall network comprises not only the FSC organization, but industry, ENGOs, certification agencies, wood product manufacturers, and retailers.

In practice, most of the demand for FSC-certified products comes from manufacturers and retailers, rather than directly from consumers (Schepers 2010). Like primary producers, manufacturers and retailers seek to differentiate themselves in the marketplace, and many choose to do so by becoming “green.” A good example is IKEA, which has established itself as a leader in sustainability. It has developed a sustainability plan that includes criteria and targets across the full breadth of its business enterprise. For its wood products, the company’s objective is to purchase at least 50% of its supplies from FSC-certified or recycled wood sources (IKEA 2014).

Another certification system in widespread use is run by the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC 2017). Like FSC, the Marine Stewardship Council has established sustainability standards, in this case for marine fisheries. It also oversees producer certification, runs a chain-of-custody system, and tracks the effects of certification. A key difference with Marine Stewardship Council certification is that it is less dependent on intermediaries. The main target is the purchase of fish at the grocery store by individual consumers.

Certification is also in place for the producers of organic agricultural products. In this case, the system, dubbed the Canada Organic Regime, is overseen by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency and is regulated under federal law. The federal government’s involvement was largely driven by European requirements related to agricultural imports. Provinces have their own systems for organic food produced and sold in the same province. Organic food standards are focused on pesticide use and soil health and make no direct mention of maintaining native biodiversity; however, they do benefit biodiversity indirectly (GOC 2018).

Although product certification does lead to improved practices (Moore et al. 2012), it is not a panacea. A fundamental limitation is that the criteria for sustainability must be achievable (Schepers 2010). If the bar is set too high, the cost of implementation will exceed the reward of certification, and producers will not participate. Therefore, certification is not awarded for achieving ecological sustainability per se, but for demonstrable progress toward that goal. The hope is that, as companies make progress, and as certification gains profile and generates market demand, it will be possible to gradually raise the standards.

Another problem is that ENGO-led certification systems like FSC face competition from industry-led schemes that have arisen in their wake. The industry-led standards tend to be easier to achieve, but this is not obvious to average consumers who lack the technical knowledge needed to discern the differences (Schepers 2010). To counter this problem, several of the larger ENGOs work behind the scenes to promote FSC in the marketplace.

One of the main organizations promoting product certification is the World Wildlife Fund (WWF). Recognizing the overwhelming challenge of educating millions of individual customers, WWF has focused its efforts on developing partnerships with strategically selected companies. The aim is to help these companies “achieve positive and measurable benefits for their businesses, while creating conservation impacts where they matter most” (WWF 2018). Part of WWF’s efforts include promoting the use of certified products, though it also works with companies on other aspects of their business.

Other groups, such as Greenpeace, also interact with businesses but tend to use a more coercive approach. A favoured tactic is to generate demand for certified products through selective targeting of high-profile retailers, which represent points of leverage. Consumers have a low tolerance for poor environmental performance and will readily punish retailers for such failings, even more than they will reward companies for positive performance (O’Rourke 2005). In addition, corporate brand and reputation are highly valued, so the involvement of even a relatively small percentage of customers can have substantial influence. Finally, the changes needed for achieving sustainability are less onerous for retailers than they are for resource companies, which means there is less resistance to change.

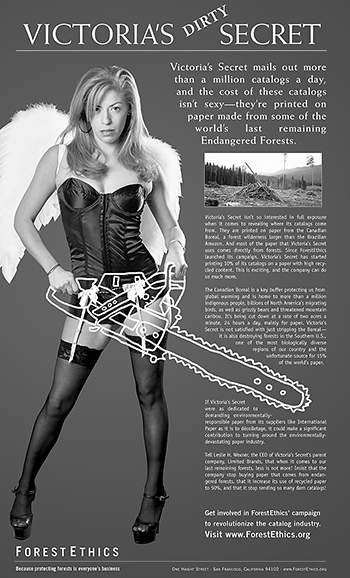

An illustrative example is the market action campaign against Victoria’s Secret by ForestEthics (now called Stand.earth) and its partners in the early 2000s. Targeting a company that sells sexy underwear may seem like an odd choice for a forest conservation initiative, but it was actually highly strategic. Victoria’s Secret is a business that sells not only underwear but an image and a lifestyle. In the 2000s, its well-known catalogue was a key component of its marketing strategy, reaching over 350 million customers each year (Merrick 2006). Producing a catalogue run of this magnitude involved killing a lot of trees—an image that did not square well with the company’s brand or its customer base, once the connection was made. These factors made the company an ideal target within a broader campaign to convert the entire catalogue industry to FSC-certified paper. After two years of campaigning, including store-front demonstrations and provocative ads (Fig. 3.10), Victoria’s Secret agreed to increase the recycled content of its paper and to give preference to FSC-certified sources. Three years later, an independent audit determined that 88% of paper purchased by Victoria’s Secret was either FSC-certified or post-consumer waste paper (Merrick 2006).

A campaign like the one against Victoria’s Secret has ripple effects that extend well beyond the company itself. Other companies, realizing that they may be next in line, often begin adjusting their practices proactively, resulting in the evolution of normative standards. The rise in demand for certified wood products, in turn, helps to create a business case for sustainable practices and certification among resource companies.

Promoting sustainability through market action is more challenging in the mining and oil and gas sectors because it is difficult to certify and trace these types of raw materials. Market-based campaigns are still utilized but in a more limited context. One approach has been to punish perceived laggards, again hoping for broader ripple effects. An example is the 2002–2004 market campaign by Greenpeace against ExxonMobil over its resistance to climate change mitigation efforts (Gueterbock 2004).

As with Victoria’s Secret, the choice of ExxonMobil was strategic. Not only was the company a perceived laggard, it had a large retail presence through its Esso gas stations that created a point of vulnerability (Gueterbock 2004). In this case, ExxonMobil did not capitulate, even though the campaign was supported by many motorists. This outcome is perhaps not surprising. The costs of sustainability are much higher for resource companies than they are for retailers like Victoria’s Secret, which only had to switch suppliers. So there is more incentive to resist. Nevertheless, the campaign did damage ExxonMobil’s brand, and affected sales to some (unknown) degree, sending a message to other companies that ignoring environmental concerns comes with tangible risks.

One further avenue of market influence on environmental protection is sustainable investing, also known as socially responsible investing (Glac 2009). Sustainable investing has been growing rapidly, and according to the US Sustainable Investment Forum, over $8 trillion is now invested in US funds that incorporate sustainability criteria (SIF 2022).

The scope of sustainable investing is broad and generally includes environmental, social, and corporate governance criteria. Companies are differentiated by these criteria and those with the best score within each industrial sector are rewarded with increased investment demand. In contrast to product certification systems, the assessment criteria for sustainability are not standardized and no attempt is made to determine whether a company’s practices are in fact sustainable. Companies are simply rewarded for doing better than their peers, and this provides the business case for improving environmental practices (Glac 2009).

Little information currently exists as to how effective sustainable investing has been in terms of actually changing company practices. Moreover, over the past few years there has been a growing backlash against the perceived misrepresentation of investment products by fund managers who stand accused of simply washing everything in green (SIF 2022). As a result, regulators and sustainability advocates are now placing increasing pressure on fund mangers to improve transparency and accountability with respect to the sale of sustainable investing products. Consider it a work in progress.

Variability in Company Attitudes and Approaches

Resource companies vary widely in their commitment to sustainability and the conservation of biodiversity. Some are progressive and willing to undertake meaningful actions, whereas others are quite recalcitrant, refusing to do more than is absolutely required.

An important determinant of environmental attitudes is company size (Hillary 2004). Small resource companies tend not to attract much public attention, largely because ENGOs usually focus their limited capacity on large companies, which make a more efficient target (Hillary 2004). Individually, large companies have more environmental impact than small companies, and they are more vulnerable to market action. Public tolerance for the environmental failings of large multinational corporations tends to be quite low, whereas the transgressions of small locally owned companies may be forgiven. Finally, small companies have less technical capacity and flexibility than large companies for implementing new approaches. Consequently, leadership in environmental practices is most often found among large resource companies (which is not to say that all large companies are progressive). Conversely, small resource companies generally prefer doing things the old way as long as possible, though there are exceptions.

Environmental attitudes are also affected by company-specific factors. For example, a forestry company with ample wood supply is more likely to embrace progressive practices than a company facing a shortfall. Senior management is another important factor. These individuals make the key decisions that set a company’s direction, so individual personalities can make a big difference. Decisions are influenced by the experience, risk tolerance, and personal biases of those involved. Thus, two companies faced with similar circumstances may come up with quite different conclusions about the best course of action.

Company attitudes and approaches toward conservation are also shaped by industry associations. Associations can have a positive effect by articulating industry norms and facilitating the dissemination of new ideas to their member companies. However, externally, industry associations can be a regressive force. The positions they present as the voice of industry in public policy debates often gravitate to the lowest common denominator among the companies they represent.

Significant differences also exist among industrial sectors. These will be discussed in Chapter 7 in association with our examination of sector-specific approaches to biodiversity conservation.