The War in the Woods

The advancement of conservation in the late twentieth century was not limited to the recovery of species at risk; it also included the management of landscapes. Landscape-based efforts began when rising environmental awareness in the 1970s led to demands for better management of industrial activity on public lands, most of which are forested.

Federal and provincial governments initially responded through commitments to manage forests for multiple values (such as wildlife), and not just timber supply. However, in practice, managers generally interpreted this directive to mean that other values were to be accommodated only to the extent that they did not significantly impinge on resource extraction (Wilson 1998). This did allow for some conservation gains, such as the protection of sites with low resource value. But fundamental changes in forest management were not forthcoming. Consequently, individuals and groups concerned about forests became progressively disillusioned with the government and their trust was eroded.

South of the border, forest management was also evolving, but along a different trajectory (MacCleery 2008). By the mid-1970s, studies had revealed that late-successional forests in the Pacific Northwest provided essential habitats for a suite of animal and plant species, including the northern spotted owl (Fig. 2.19). In response, conservation-minded scientists began to develop and promote new ecologically based approaches to forestry. These developments, together with a growing wilderness preservation movement, fuelled intense debate about the management of US public forests, most of which were under federal jurisdiction.

The turning point came in March 1989, when federal district court judge William Dwyer issued an injunction on the harvest of virtually all national forest timber within the range of the northern spotted owl (i.e., most of the Pacific Northwest). He ordered the Forest Service to revise its standards and guidelines to ensure that the northern spotted owl remained viable, as required under the US Endangered Species Act.

When the dust finally settled, in the early 1990s, a new system of forest management, referred to as ecosystem management (see Chapter 7), had been adopted for all US national forests. Harvest volumes, which had been relatively consistent between 1960 and 1989, fell by over 80%, reflecting what the US Forest Service deemed necessary for maintaining the ecological integrity of national forests and the viability of species dependent on old-growth habitat (MacCleery 2008). These changes were backstopped by the US Endangered Species Act, which had no counterpart in Canada at the time. Nevertheless, Canadian conservationists were emboldened by the developments to the south and determined to see ecosystem management concepts applied here.

Another important development affecting the course of Canadian conservation was the release of Our Common Future (also known as the Brundtland Report) by the World Commission on Environment and Development in 1987 (WCED 1987). This high-profile report drew international attention to the importance of balancing economic and environmental objectives through sustainable development, which was defined as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (WCED 1987, p. 43). The report also called for a tripling of the world’s protected areas to achieve adequate representation of all ecosystems. This recommendation formed the basis of the 12% protection target that was popularized in many countries, including Canada (see Chapter 8).

Our Common Future and the old-growth forest controversy in the US were elements of the broad resurgence of global environmentalism in the late 1980s that we encountered earlier in our discussion of species at risk legislation. In this milieu of heightened environmental salience, simmering discontent with forest management across Canada reached a flashpoint, resulting in the so-called “War in the Woods.” During this period, the media once again displayed heightened sensitivity to environmental issues, and local stories that had previously lurked in obscurity were now cast onto the national and sometimes international stage.

Although the War in the Woods affected forests from coast to coast, BC was ground zero (Fig. 2.20). Most of the initial battles involved opposition to proposed harvesting in southern BC’s last pristine watersheds, including South Moresby Island, the Stein Valley, and Clayoquot Sound. These early campaigns were primarily based on a wilderness preservation agenda, rather than a forest management agenda.

Conservation groups advanced their forest protection objectives through broad networks of supporters and public outreach. The groups were adept at using symbolism and emotional appeal to win support for their cause, feeding into shifts in societal values. They were also highly effective in discrediting the forest industry’s old-growth liquidation program and out-of-date harvesting practices. In later stages, the groups also used international public opinion and boycotts as leverage. The forest industry, for its part, spent millions of dollars on advertising campaigns, but public perceptions of the industry continued to decline despite these efforts (Wilson 1998).

In terms of public profile, the high-point of the BC campaigns occurred in the summer of 1993 when over 800 people were arrested for blocking logging trucks in Clayoquot Sound—the largest act of civil disobedience in Canadian history to that point in time. Television sets across the country beamed images of hundreds of people, from students to raging grannies, being dragged off to jail in defiance of an industry that had been the lifeblood of the BC’s economy for almost a century. The protests did not result in immediate capitulation by the government, but most of the areas contested in the early campaigns were eventually protected.

The events in BC had ripple effects across the country, raising awareness and leading to forestry- related protests in many areas. The objectives and nature of the protests were different in each case. In Alberta, the trigger was the allocation, in 1987, of vast northern timberlands without public hearings, scientific study, or regional planning (Pratt and Urquhart 1994). In Ontario, the focal point was the proposed logging, in 1989, of the old-growth pine forest in the Temagami region, one the last of its kind in eastern North America. One of the protesters arrested in this case was Bob Rae, who would later serve as premier of Ontario. In Quebec, the film L’Erreur Boréale, directed by a popular folk singer, Richard Desjardins, generated public outrage over forestry practices in the province and demands for change. Forest protests even reached the east coast, as New Brunswickers battled to save the Christmas Mountains from harvest.

As the 1990s progressed, the place-based wilderness preservation agenda began to merge with the ecosystem management agenda imported from the US. A broad consensus emerged to protect 12% of Canada’s lands and waters in sites that provided representation of all of Canada’s natural regions. World Wildlife Fund Canada provided initial leadership through its ten-year Endangered Spaces campaign, launched in 1989 (Hummel 1989).

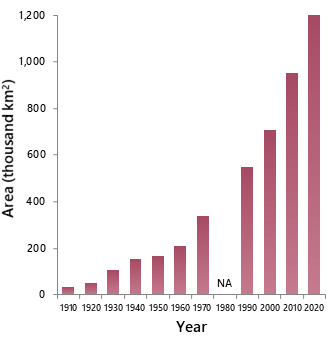

Several provinces initiated formal planning programs in the 1990s to complete or augment their parks systems, and efforts are still ongoing in some regions (Fig. 2.21). As of 2022, 12.6% of Canada’s terrestrial area (land and freshwater) was protected, along with 9.1% of Canada’s marine territory (ECCC 2022). Legislation governing parks was also strengthened during the late 1980s and 1990s. Of particular note was an amendment of the Canada National Parks Act, in 1988, which established that the first priority of national parks was to maintain or restore ecological integrity (GOC 2000).

The War in the Woods also led to changes in forest management which emphasized the maintenance of ecological integrity over the production of wood fibre. This shift was heralded by the Canada Forest Accord, signed by the Canadian Council of Forest Ministers in 1992 (CCFM 1992). As stated in the Accord, the goal of forest managers was to “maintain and enhance the long-term health of our forest ecosystems, for the benefit of all things both nationally and globally, while providing environmental, economic, social and cultural opportunities for the benefit of present and future generations” (CCFM 1992, p. 1).

Although federal, provincial, and territorial forestry ministers all signed the Accord, implementation was inconsistent across the country. The federal government could not enforce minimum standards or even ensure a coordinated response because authority over forest management rested with the provinces. The provinces blazed their own trails; some were progressive, and others were not.

BC and Ontario both passed legislation in 1994 that enshrined the goal of forest sustainability in law and set forth new requirements for forestry practices (GOBC 1994; GOO 1994). Both provinces also initiated land-use planning initiatives in the 1990s aimed at resolving broader conflicts related to land use. Forest legislation was also modernized during the 1990s in Saskatchewan, Quebec, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland. The approaches varied but all included a commitment to forest sustainability and provisions for public participation (Boyd 2003). In contrast, Alberta, Manitoba, and New Brunswick made no effort to update their forestry legislation during this period.

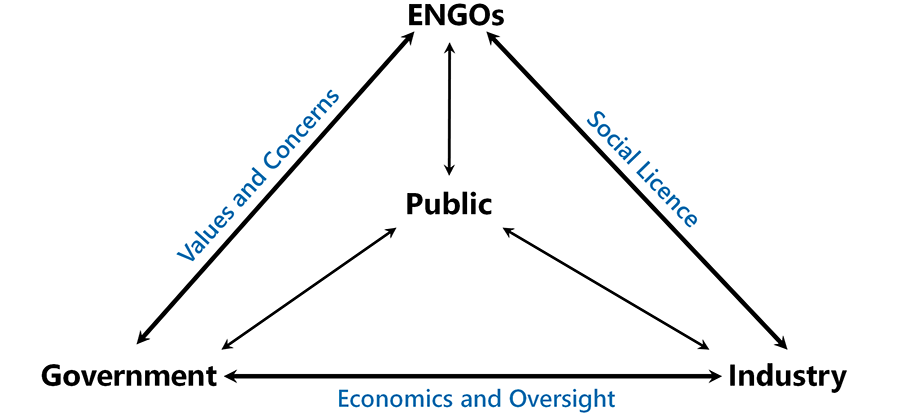

The War in the Woods also disrupted the monopoly on decision making long held by government and industry. A large majority of the public now favoured forest protection over development and these values could no longer be marginalized (Lance et al. 2005). Furthermore, forest management was no longer a quiet, private affair. Conservation groups had expanded tremendously in terms of the number of members, financial resources, technical knowledge, and experience in communications. They, together with other engaged stakeholders (including Indigenous groups), were now a permanent fixture of the policy landscape and could not be sidelined. Though it was still a David and Goliath scenario with respect to financial resources and technical capacity, it was understood by all that conservationists were representing the conservation-minded public—like the part of an iceberg you see above the water line.

A related development was that some conservation groups, dissatisfied with years of half-hearted government responses, began to engage directly with forestry companies under the rubric of social licence (see Chapter 3). These efforts included direct negotiations over practices, the development of product certification schemes, and boycotts of selected high-profile companies. In some cases, these efforts proved to be quite effective.

For example, in Alberta, Alberta-Pacific Forest Industries became a lightning rod for popular discontent over forestry expansion in the late 1980s, making it the target of protests. This newly formed company emerged from its trial by fire with heightened environmental sensitivity. It became an early adopter of ecosystem management concepts coming from the US and quickly evolved into a vocal champion of progressive forestry, serving in the role the provincial government had abdicated (see Case Study 1, p. 259).

Because of these changing political dynamics, land-use decision making by the late 1990s was far more complex than it ever had been in the past (Luckert et al. 2011). The simple government-industry axis of information flow and decision making had evolved into a tangled web of interactions (Fig. 2.22). Although the large protests eventually subsided, governments, companies, and conservation groups continued to compete for the hearts and minds of the voting and consuming public in a “cold war” of claims and counterclaims about management successes and failures.

Unfortunately, the on-the-ground changes arising from the War in the Woods were much less impressive than might be expected given the grand commitments to forest sustainability made by governments and industry. In the US Pacific Northwest, maintaining the integrity of national forests meant reducing harvest levels by 80% (MacCleery 2008). In Canada, harvesting rates in the 1980s and 1990s did not fall at all; they actually increased (Fig. 2.8). Furthermore, late-successional forests generally remained primary targets for harvesting.

These differences reflect the simple fact that, in Canada, mill requirements continued to serve as the primary determinant of how much wood was cut. Even in BC, a leader of forestry reform, the Minister of Forests decreed that the average reduction in annual allowable cut resulting from the province’s new forestry regulations would be no more than 6% (Wilson 1998). This defined, in no uncertain terms, the extent to which forestry reforms would be allowed to proceed. Harvest levels of forestry companies in other provinces were also maintained near their historical rates (Boyd 2003). As for lands taken out of production as protected areas, these were more than offset by new forestry allocations in other regions.

To be sure, several important changes did occur. Many ecologically important areas were protected during this period, including irreplaceable old-growth forests in southern BC. On the managed land base, though harvest rates did not decline, substantive improvements were made to harvesting practices. For example, progressive companies began varying the size and shape of cutblocks and leaving patches of live trees after harvest in an attempt to emulate natural disturbance processes (see Chapter 7). These efforts were guided by research undertaken by forestry companies, governments, and the academic community that sought to describe natural forest patterns and processes and to quantify the effects of human disturbances on forested ecosystems.

In summary, the War in the Woods was perhaps more evolutionary than revolutionary. But it did usher in a distinctly new era, featuring the actors, decision processes, and legacies that characterize forest management today.