Making a Difference

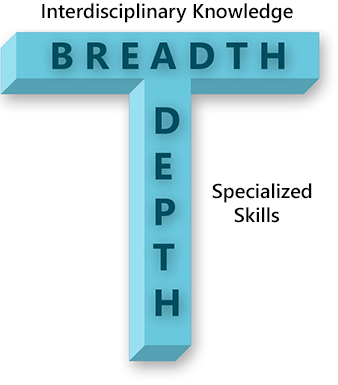

In this last section, we turn to effectiveness at the personal level. The practice of conservation requires a combination of broad and specialized knowledge—a so-called “T-shaped” skill set (Fig. 12.2; Schwartz et al. 2017). The stem of the T represents in-depth knowledge of a specific discipline. This knowledge is generally gained through formal study, typically in a subfield of biology but also in fields such as law, policy, social science, and economics.

The top bar of the T represents basic competence in a broad suite of ancillary fields relevant to working at the interface between science and policy (Jacobson and Duff 1998). Interdisciplinary knowledge and skills are typically acquired through self-directed study and work experience rather than university classes alone. This form of learning never really ends. The skills of greatest utility for advancing conservation include:

- Communication ability. Conservation invariably involves working with people, including colleagues, stakeholders, funders, elected officials, and the public. Therefore, the ability to communicate effectively, both orally and in written form, is a fundamental skill required by conservation practitioners. Effective communication also entails effective listening and a willingness to see the world from other points of view.

- Decision-making skills. Conservation practitioners should understand the principles of structured decision making and be able to apply them. Structured decision making should not be viewed as a rigid template, but as an effective way of thinking through problems that can be flexibly adapted to specific situations. Decision making also requires analytical skills for identifying problems, clarifying objectives, evaluating options, and so forth.

- Management skills. Besides making decisions, conservation practitioners need to oversee projects, facilitate groups, resolve conflicts, and accomplish various other tasks that fall under the general heading of management. Effective management requires good interpersonal and organizational skills as well as leadership ability.

- Interdisciplinary knowledge. To be effective, conservation practitioners need to understand the socio-political arena in which they are working. This includes institutional structures, relevant laws and policies, economic drivers, and the perspectives of the main stakeholders.

Effectiveness is also influenced by the way that personal resources, such as time, effort, and influence are allocated. Conservation practitioners should focus their efforts on initiatives that provide the greatest potential for advancing conservation, taking one’s abilities and terms of employment into account. Finding an organization that provides a good fit with one’s interests and abilities is part of this optimization process.

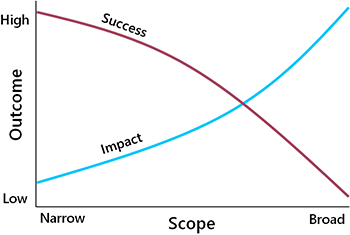

From our earlier discussion of the correlates of success, it may be tempting to conclude that it is best to focus on simple, well-contained conservation problems. But the calculus of effectiveness is deeper than that. The intractability of high-level initiatives is offset by their potential to benefit large numbers of species across wide spatial extents (Fig. 12.3). Even small conservation gains at this level can be important for maintaining overall biodiversity, and over the long term, these small gains can add up. Moreover, this is where the root causes of conservation problems are addressed. The upshot is that prioritization decisions are never easy, and they merit a thoughtful, structured process. Periodic reassessment is also important, because the parameters are constantly changing (e.g., conservation threats, conservation resources, knowledge gaps, and political windows of opportunity).

Effectiveness should also be maximized within individual projects. Problems should be approached holistically and with an outcome-oriented mindset. The idea is to begin with the end in mind and let the final objective guide the choice of actions. This approach avoids the trap of “busy work,” where much is being done but little is being accomplished.

With respect to specific practices, it is important to learn from the experience of others. Although the outcomes of conservation initiatives are not consistently reported, papers on conservation methods, tailored to specific species and problems, have slowly accumulated over the years. The collective body of knowledge is now quite large. A useful resource is the Conservation Evidence website, which provides a searchable database of conservation techniques based on over 5,000 published studies. This site provides a gateway to the literature.

In many cases, overcoming barriers to conservation requires innovative thinking and a willingness to be flexible. This can mean stepping out of one’s comfort zone. The biologists hired by Al-Pac never expected to be government lobbyists, and the biologists managing walleye never expected to be workshop facilitators. Yet these activities were essential to success. The point is not that individual conservation practitioners can or should do everything, but that adaptability and a laser focus on outcomes are central to effectiveness.

Based on his long career in fisheries management, Carl Walters (2007) offers additional insights into what contributes to successful project outcomes, focusing on the role of individual conservation practitioners:

The leaders have been people who (1) have a broad overview of the decision-making and implementation process, along with intimate knowledge of all the people and technical/administrative details involved in each step in the process; (2) are very well organized in terms of planning who, what, where, and when specific activities and actions are needed; (3) simply refuse to take no for an answer on the many occasions when contributors to the process offer excuses for inaction; and (4) are willing to devote their whole career, for extended periods of time (typically several years), to the implementation process. (p. 3)

Finally, it is important to recognize that conservation evolves slowly, in fits and starts. It is a long game that demands patience, persistence, and an optimistic “the glass is half full” outlook. Setbacks are many, and conservation practitioners need to be able to accept them, reassess, and move on. It is also important to recognize windows of opportunity when they arise and to act decisively when they do. In the final analysis, conservation practitioners cannot solve all of the world’s environmental problems, but we have an outsize effect relative to our numbers, and we can make a significant difference.