How Much Is Enough?

Determining the appropriate amount of protection is one of the most challenging aspects of conservation planning (Wiersma and Nudds 2006; Wiersma and Sleep 2018). It is not just a matter of assessing biological need. In real-world applications, trade-offs with competing land-use objectives also have to be considered. The protection of public lands never occurs without this step.

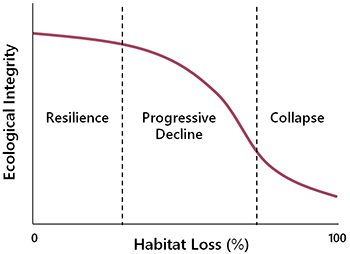

From a strictly biocentric perspective, the preferred solution is to protect the entire landscape. Thus, any protection target below 100% represents a compromise from a biocentric view. The ecological consequences of this compromise depend on how severely the unprotected habitat is ultimately degraded (Fig. 8.4).

Field studies suggest that the effects of habitat loss on biodiversity outcomes are nonlinear (Swift and Hannon 2010; Richmond et al. 2015). Pristine systems are inherently resilient and can withstand small amounts of habitat loss without significant consequences (Fig. 8.4). But as the degree of habitat loss increases, the abundance of sensitive species eventually begins to decline, and certain ecological functions become impaired. Once the majority of the original habitat is lost, a tipping point may be reached where widespread species extirpation occurs.

For planning purposes, it would be useful to know exactly where the tipping point for ecological integrity is, but this information is usually unavailable. Each system is unique, particularly with regard to the types of anthropogenic disturbances present on the working landscape (van der Hoek et al. 2015). It makes a big difference whether the disturbed areas experience complete habitat loss or just a reduction in habitat quality. For most real-world conservation planning, we only have simple qualitative curves, like Fig. 8.4, to work with (Lindenmayer et al. 2005).

Trade-offs with other land-use objectives are best handled through a structured decision-making process. The aim is to compare the benefits and costs of habitat protection across a range of reserve size possibilities using the best available information. From Fig. 8.4, we see that protection provides diminishing returns at high target levels (i.e., within the resilience zone). The inverse relationship holds for costs. Costs are magnified at high levels of protection because little flexibility remains for avoiding areas with high resource potential. The optimal balance between benefits and costs is ultimately a matter of social choice.

Unfortunately, structured, evidence-based approaches are the exception rather than the rule when it comes to setting protection targets. Informal approaches are much more common. Deliberations typically give little or no consideration to the specific biodiversity outcomes that protection is meant to achieve (Svancara et al. 2005). In such cases, it is impossible to determine whether the optimal balance between protection and development has been achieved because the trade-offs are never formally assessed.

Despite the weak foundation of many protection targets, it would be wrong to assume that these targets have been unhelpful. In fact, much has been accomplished. One of the most widely used targets originated with a 1987 report on sustainable development by the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED 1987). Without any justification beyond the general notion of balancing development and environmental protection, the Commission proposed that the world’s existing base of protected areas should be tripled from 4% to 12%.

The 12% target was imported to Canada through the World Wildlife Fund’s Endangered Spaces Campaign (1989–2000), which resulted in a doubling in the extent of Canada’s protected area network (WWF 2010). The 12% target was important because it provided a bold, yet achievable, goal that inspired and engaged diverse segments of Canadian society and motivated political action.

In 2010, the UN Convention on Biological Diversity set a new international protection target of 17% of terrestrial areas and 10% of marine areas (UN 2010). In 2016, the federal, provincial, and territorial deputy ministers responsible for protected areas established a working group committed to achieving the 17% target in Canada.

In 2022, the UN Convention of Biological Diversity again boosted its protection target, this time to 30% by 2030 for both terrestrial and marine areas (UN 2022). The federal government in Canada has likewise begun referencing the 30% target as its protection goal (GOC 2022b). However, behind this headline there has been a shift in the meaning of the term “protection.”

Henceforth, protection targets will include “other effective area-based conservation measures.” These sites are intended to “achieve long-term and effective conservation of biodiversity, even when the land is managed for different purposes” (GOC 2022b). There is as yet no clarity about how the management of these sites will differ from existing approaches, such as sustainable forest management (see Chapter 7). Time will tell whether this approach will lead to a meaningful gain in protection or whether it is simply a method for the spurious inflation of protection targets. Provincial involvement is also an open question at this time.

In summary, protected areas are one of the most effective tools for conserving biodiversity, but they present serious conflicts with other land-use objectives. Compromise is usually necessary. To date, most policy-based protection targets have been far below the level needed to forestall declines in biodiversity (Svancara et al. 2005). That said, protection targets have been trending upwards over time and could continue to do so. Much depends on public perceptions and support for protection. There is also a need for effective and transparent decision making.

Stretch Targets

In recent years, a variety of conservation organizations and academic researchers have been advancing a protection agenda under the tagline “nature needs half” (Noss et al. 2012; Locke 2014; Dinerstein et al. 2017). The 50% target is portrayed as “science based,” but strictly speaking, targets are informed by science, not based on science. From an ecological perspective, there is nothing special about the 50% mark. It is above the point of catastrophic change but well below the point at which ecological decline is detectable (Fig. 8.4).

The selection of 50% as a protection target is basically an expression of risk tolerance—a value judgment on the part of the conservationists involved. Their intent is to reframe the public discourse about protected areas by advancing the possibility of protecting much more than 12% or 17% of the landscape, where opportunities exist. Their general point is that we should not be fixated on averting catastrophic ecological loss—we should aspire to maintain a high level of ecological integrity. The appeal of the 50% target is that it is simple and clean, and the tagline “nature needs half” is compelling. As such, it is well suited for its role in conservation advocacy.