4.3: Conflict Management Styles

Conflict Management Styles

Thomas Kilmann Conflict Styles Inventory

Would you describe yourself as someone who prefers to avoid conflict? Do you like to get your way? Are you good at working with someone to reach a solution that is mutually beneficial? Odds are that you have been in situations where you could answer yes to each of these questions, which underscores the important role context plays within conflict and conflict management styles. The way we view and deal with conflict is learned and contextual.

Is the way you handle conflict similar to the way your parents handle conflict? If you’re of a certain age, you are likely predisposed to answer this question with a certain “No!” However, research shows that there is an intergenerational transmission of traits related to conflict management. As children, we test out different conflict resolution styles we observe within our families, our parents and our siblings. Later, as we enter adolescence and begin developing platonic and romantic relationships outside the family, we begin testing what we’ve learned from our parents in other settings. If a child has observed and used negative conflict management styles with siblings or parents, he or she may exhibit those same behaviours with non–family members (Reese-Weber & Bartle-Haring, 1998).

There has been much research done on different types of conflict management styles, which are communication strategies that attempt to avoid, address, or resolve a conflict. Keep in mind that we don’t always consciously choose a style. We may instead be caught up in the emotion and become reactionary.

The strategies we explore in future chapters will illustrate effective conflict management processes that may allow you to slow down your own reaction process and turn your reaction into a thoughtful response instead.

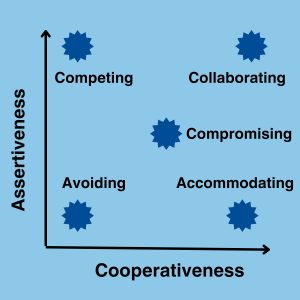

The five strategies for managing conflict are competing, avoiding, accommodating, compromising, and collaborating. Each of these conflict styles accounts for the importance we place on our goals and the importance we place on our relationships.

In order to better understand the elements of the five styles of conflict management, we will apply each to the following scenario: Rosa and George have been married for seventeen years. Rosa is growing frustrated because George continues to give money to their teenage daughter, Casey, even though they decided to keep their teenager on a fixed allowance to try to teach her about responsibility. While conflicts regarding money and child-rearing are very common, we will see the numerous ways that Rosa and George could address this problem.

Competing

The competing style of conflict management indicates a high importance for your goals and low importance for your relationship. In other words, one party attempts to win by gaining concessions or consent from another. When we compete, we are striving to “win” the conflict, potentially at the expense or “loss” of the relationship. One way we may gauge our win is by being granted or taking concessions from the other person. For example, if George gives Casey extra money behind Rosa’s back, he is taking an indirect competitive route resulting in a “win” for him because he got his way. The competing style also involves the use of power, which can be noncoercive or coercive (Sillars, 1980).

Noncoercive strategies include requesting and persuading. When requesting, we suggest the conflict partner change a behaviour. Requesting doesn’t require a high level of information exchange. When we persuade, however, we give our conflict partner reasons to support our request or suggestion, meaning there is more information exchange, which may make persuading more effective than requesting. Rosa could try to persuade George to stop giving Casey extra allowance money by bringing up their fixed budget or reminding him that they are saving for a summer vacation.

Coercive strategies violate standard guidelines for ethical communication and may include aggressive communication directed at rousing your partner’s emotions through insults, profanity, and yelling, or through threats of punishment if you do not get your way. If Rosa is the primary income earner in the family, she could use that power to threaten to take George’s ATM card away if he continues giving Casey money.

In all these scenarios, the “win” that could result is only short-term and can lead to conflict escalation. Interpersonal conflict is rarely isolated, meaning there can be ripple effects that connect the current conflict to previous and future conflicts. George’s behind-the-scenes actions or Rosa’s confiscation of the ATM card could lead to built-up negative emotions that could further test their relationship. It is important to note that there is a pattern of verbal escalation: requests, persuasion, demands, complaints, angry statements, threats, harassment, and verbal abuse (Johnson & Roloff, 2000).

The competing style of conflict management is not the same thing as having a competitive personality. Competition in relationships isn’t always negative, and people who enjoy engaging in competition may not always do so at the expense of another person’s goals. In fact, research has shown that some couples engage in competitive shared activities like sports or games to maintain and enrich their relationship (Dindia & Baxter, 1987).

Avoiding

The avoiding style of conflict management often indicates low importance of your goals and your relationship, and no direct communication about the conflict takes place. Of note, in some cultures that emphasize group harmony over individual interests, and even in some situations in the United States, avoiding a conflict can indicate attributing high importance to your relationship. In general, avoiding doesn’t mean that there is no communication about the conflict. You cannot not communicate.

Even when we try to avoid conflict, we may intentionally or unintentionally give our feelings away through our verbal and nonverbal communication. Rosa’s sarcastic tone as she tells George that he’s “Soooo good with money!” and his subsequent eye roll both bring the conflict to the surface without specifically addressing it.

The avoiding style is either passive or indirect, meaning there is little information exchange, which may make this strategy less effective than others. We may decide to avoid conflict for many different reasons, some of which are better than others. If you view the conflict as having little importance to you, it may be better to ignore it. If the person you’re having conflict with will only be working in your office for a week, you may perceive the conflict to be temporary and choose to avoid it and hope that it will solve itself. If you are not emotionally invested in the conflict, you may be able to reframe your perspective and see the situation in a different way, therefore resolving the issue. In all these cases, avoiding doesn’t really require an investment of time, emotion, or communication skills, so there is not much at stake to lose.

Avoidance is not always an easy conflict management choice, because sometimes the person we have conflict with isn’t a temp in our office or a weekend houseguest. While it may be easy to tolerate a problem when you’re not personally invested in it or view it as temporary, when faced with a situation like Rosa and George’s, avoidance would just make the problem worse. For example, avoidance could first manifest as changing the subject, then progress from avoiding the issue to avoiding the person altogether, intense resentment, and even ending the relationship.

Indirect strategies of hinting and joking also fall under the avoiding style. While these indirect avoidance strategies may lead to a buildup of frustration or even anger, they allow us to vent a little of our built-up steam and may make a conflict situation more bearable. When we hint and hope people “read between the lines”, we drop clues that we hope our partner will find and piece together to see the problem and hopefully change, thereby solving the problem without any direct communication. In almost all the cases of hinting that I have experienced or heard about, the person dropping the hints overestimates their partner’s detective abilities.

For example, when Rosa leaves the bank statement on the kitchen table in hopes that George will realize how much extra money he is giving Casey, George may simply ignore it or even get irritated with Rosa for not putting the statement with all the other mail. We also overestimate our partner’s ability to decode the jokes we make about a conflict situation. It is more likely that the receiver of the jokes will think you’re genuinely trying to be funny or feel provoked or insulted than realize the conflict situation that you are referencing. So more frustration may develop when they don’t “read between the lines”, which often leads to a more extreme form of hinting/joking.

Accommodating

The accommodating style of conflict management that may indicate low importance of your goals and high importance of your relationship, is often viewed as passive or submissive, in that someone complies with or obliges another without providing personal input. The context for and motivation behind accommodating play an important role in whether or not it is an appropriate strategy. Generally, we accommodate because we are being generous, we are obeying, or we are yielding (Bobot, 2010). If we are being generous, we accommodate because we genuinely want to; if we are obeying, we don’t have a choice but to accommodate (perhaps due to the potential for negative consequences or punishment); and if we yield, we may have our own views or goals but give up on them due to fatigue, time constraints, or because a better solution has been offered.

Accommodating can be appropriate when there is little chance that our own goals can be achieved, when we don’t have much to lose by accommodating, when we feel we are wrong, or when advocating for our own needs could negatively affect the relationship.(Warren & Spangle, 2000). The occasional accommodation can be useful in maintaining a relationship—remember earlier we discussed putting another’s needs before your own as a way to achieve relational goals. For example, Rosa may say, “It’s OK that you gave Casey some extra money; she did have to spend more on gas this week since the prices went up.” However, being a team player can slip into being a pushover, which people generally do not appreciate. If Rosa keeps telling George, “It’s OK this time,” they may find themselves short on spending money at the end of the month. At that point, Rosa and George’s conflict may escalate as they question each other’s motives, or the conflict may spread if they direct their frustration at Casey and blame it on her irresponsibility.

Research has shown that the accommodating style is more likely to occur when there are time restraints and less likely to occur when someone does not want to appear weak (Cai & Fink, 2002). If you’re standing outside the movie theatre and two movies are starting, you may say, “Let’s just have it your way,” so you don’t miss the beginning. If you’re a new manager at an electronics store and an employee wants to take Sunday off to watch a football game, you may say no to set an example for the other employees.

Compromising

The compromising style of conflict management shows moderate importance of your goals and your relationship and may indicate there is a low investment in the conflict and/or the relationship. Even though we often hear that the best way to handle a conflict is to compromise, the compromising style isn’t a win/win solution; it is a partial win/lose. In essence, when we compromise, we give up some or most of what we want. It’s true that the conflict gets resolved temporarily, but lingering thoughts of what you gave up could lead to a future conflict. Compromising may be a good strategy when there are time limitations or when prolonging a conflict may lead to relationship deterioration. Compromise may also be good when both parties have equal power or when other resolution strategies have not worked (Macintosh & Stevens, 2008).

A negative of compromising is that it may be used as an easy way out of a conflict. The compromising style is most effective when both parties find the solution agreeable. Rosa and George could decide that Casey’s allowance does need to be increased and could each give ten more dollars a week by committing to taking their lunch to work twice a week instead of eating out. They are both giving up something, and if neither of them has a problem with taking their lunch to work, then the compromise is equitable. If the couple agrees that the twenty extra dollars a week should come out of George’s golf budget, the compromise isn’t as equitable, and George, although he agreed to the compromise, may end up with feelings of resentment.

Collaborating

The collaborating styles of conflict management shows high importance of your goal and your relationship and usually indicates investment in the conflict and/or relationship. Although the collaborating style takes the most work in terms of communication competence, it ultimately leads to a win/win situation in which neither party has to make concessions because a mutually beneficial solution is discovered or created. The obvious advantage is that both parties are satisfied, which could lead to positive problem solving in the future and strengthen the overall relationship. For example, Rosa and George may agree that Casey’s allowance needs to be increased and may decide to give her twenty more dollars a week in exchange for her babysitting her little brother one night a week. In this case, they didn’t make the conflict personal but focused on the situation and came up with a solution that may end up saving them money. The disadvantage is that this style is often time-consuming, and only one person may be willing to use this approach while the other person is eager to compete to meet their goals or is willing to accommodate.

Here are some tips for collaborating and achieving a win/win outcome (Hargie, 2011)

- Do not view the conflict as a contest you are trying to win.

- Remain flexible and realize there are solutions yet to be discovered.

- Distinguish the people from the problem (don’t make it personal).

- Determine what the underlying needs are that drive the other person’s demands (needs can still be met through different demands).

- Identify areas of common ground or shared interests that you can work from to develop solutions.

- Ask questions for clarification and to help you understand their perspective.

- Listen carefully and provide verbal and nonverbal feedback.

The Conflict Styles framework supplies us with a way to analyze our, and others, behaviour in a conflict situation. Sometimes, a difference in conflict style is the conflict (someone with a competing style and someone with an avoiding style could be in conflict about the way to approach conflicts), or at the very least different conflict styles add a second layer to the actual conflict.

For example, If you are experiencing a process goal interference with a roommate about cleaning, that conflict could escalate based on a difference in conflict style if you are more compromising and the other person is more competitive. We will discuss how to handle this in more specifics in future chapters. If you currently find yourself in a conflict that is caused by or escalated by a difference in conflict styles, you can try highlighting those differences and discuss how you want to talk about the conflict you are experiencing, not the specifics of what conflict you are experiencing.

Another interesting part of the Conflict Styles framework is that there isn’t a “right” or “best” style. This isn’t about collaborating all the time. Rather, it is about learning when to use which style. Utilizing this tool, you can ask yourself, how important are my goals? And how important are my relationships? If you have low importance of goals and low importance of your relationship in a conflict situations, you should avoid the argument. If you have high importance of goals and high importance of your relationship, you should collaborate.

_________

Adaptation: Material in this chapter has been adapted from “A Primer on Communication Studies” is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA3.0