What is Geology?

In its broadest sense, geology is the study of Earth—its interior and its exterior surface, the minerals, rocks and other materials that are around us, the processes that have resulted in the formation of those materials, the water that flows over the surface and through the ground, the changes that have taken place over the vastness of geological time, and the changes that we can anticipate will take place in the near future. Geology is a science, meaning that we use deductive reasoning and scientific methods to understand geological problems. It is, arguably, the most integrated of all of the sciences because it involves the understanding and application of all of the other sciences: physics, chemistry, biology, mathematics, astronomy, and others. But unlike most of the other sciences, geology has an extra dimension, that of time—deep time—billions of years of it. Geologists study the evidence that they see around them, but in most cases, they are observing the results of processes that happened thousands, millions, and even billions of years in the past. Those were processes that took place at incredibly slow rates—millimetres per year to centimetres per year—but because of the amount of time available, they produced massive results.

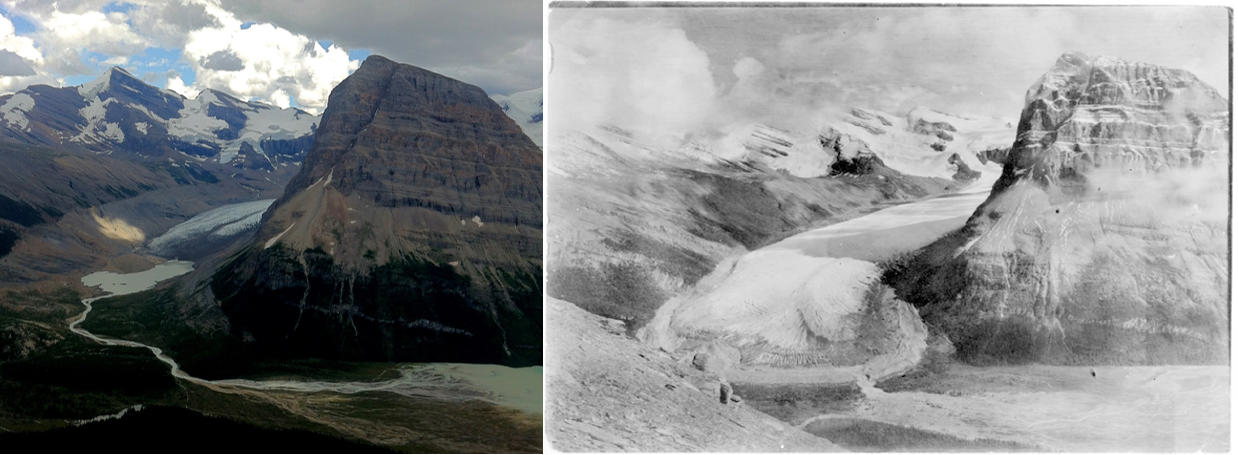

Geology is displayed on a grand scale in mountainous regions, perhaps nowhere better than the Rocky Mountains in Canada (Figure I1). The peak on the right is Rearguard Mountain, which is a few kilometres northeast of Mount Robson, the tallest peak in the Canadian Rockies (3,954 metres). The large glacier in the middle of the photo is the Robson Glacier. The river flowing from Robson Glacier drains into Berg Lake in the bottom right. There are many geological features portrayed here. The sedimentary rock that these mountains are made of formed in ocean water over 500 million years ago. A few hundred million years later, these beds were pushed east for tens to hundreds of kilometres by tectonic plate convergence and also pushed up to thousands of metres above sea level. Over the past two million years this area—like most of the rest of Canada—has been repeatedly glaciated, and the erosional effects of those glaciations are obvious.

The Robson Glacier is now only a small remnant of its size during the Little Ice Age of the 15th to 18th centuries, and even a lot smaller that it was just over a century ago in 1908. The distinctive line on the slope on the left side of both photos shows the elevation of the edge of the glacier a few hundred years ago. Like almost all other glaciers in the world, it receded after the 18th century because of natural climate change, is now receding even more rapidly because of human-caused climate change.

Geology is also about understanding the evolution of life on Earth; about discovering resources such as water, metals and energy; about recognizing and minimizing the environmental implications of our use of those resources; and about learning how to mitigate the hazards related to earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and slope failures. Many of these aspects of geology are covered in this textbook and will be discussed in the lab.

What are scientific methods?

There is no single method of inquiry that is specifically the “scientific method”; furthermore, scientific inquiry is not necessarily different from serious research in other disciplines. The most important thing that those involved in any type of inquiry must do is to be skeptical. As the physicist Richard Feynman once said: the first principle of science is that “you must not fool yourself—and you are the easiest person to fool.” A key feature of serious inquiry is the creation of a hypothesis (a tentative explanation) that could explain the observations that have been made, and then the formulation and testing (by experimentation) of one or more predictions that follow from that hypothesis.

For example, we might observe that most of the cobbles in a stream bed are well rounded, and then derive the hypothesis that the rocks are rounded by transportation along the stream bed. A prediction that follows from this hypothesis is that cobbles present in a stream will become increasingly rounded as they are transported downstream. An experiment to test this prediction would be to place some angular cobbles in a stream, label them so that we can be sure to find them again later, and then return at various time intervals (over a period of years) to carefully measure their locations and roundness.

A critical feature of a good hypothesis and any resulting predictions is that they must be testable. For example, an alternative hypothesis to the one above is that an extraterrestrial organization creates rounded cobbles and places them in streams when nobody is looking. This may indeed be the case, but there is no practical way to test this hypothesis. Most importantly, there is no way to prove that it is false, because if we aren’t able to catch the aliens at work, we still won’t know if they did it!

Media Attributions

- Figure I1 (left): © Steven Earle. CC-BY-4.0

- Figure I1 (right): A.P. Coleman. Public domain. Source: Arthur P. Coleman Collection at Victoria University Library.