What is the NiMe diet?

Non-industrialized dietary patterns are complex and differ among populations and throughout human history. However, most share certain characteristics: they are low in energy-dense processed foods (high in added sugar, fat, and chemicals that damage the microbiome) and rich in vegetables, fruits, legumes, nuts, and seeds that provide dietary fibre in amounts that exceed what is currently recommended in dietary guidelines. Most non-industrialized human populations consume animal proteins, but often in lower amounts than plant-based foods.

Leveraging the microbiome research described above, we were determined to create a diet that mimics non-industrialized dietary habits to restore gut microbiomes, and that everyone could use to benefit their health: The Non-industrialized Microbiome restore diet, or NiMe™ (pronounced Nee-Mee).

The scientific framework of the NiMe diet

The diet is based on a scientific framework informed by four pillars:

- Evolution: Humans and their microbiomes evolved together over millennia in a nutritional environment completely different than that of today. We considered the structural and compositional characteristics of food to create recipes that align more closely with the diet humans and their microbiomes consumed over the course of evolution, before the onset of industrialization.

- Ecology: The human gut microbiome is a diverse community of bacteria, fungi, viruses, and other microbes that interact with each other and produce compounds that are sensed throughout the human body. We consider how foods impact this complex ecosystem and its metabolic output, and how the industrialization and processing of foods have altered these interactions and disrupted the microbiome.

- Mechanisms: We consider the mechanisms by which (i) food components and (ii) gut microbes and the compounds they produce in response to diet influence metabolic and immunological processes in the human body. We focus specifically on how changes in the structure and composition of food through industrialization alter the effects of diet on human biology and host-microbe interactions that underpin chronic pathologies.

- Nutrition: Large observational studies have determined the long-term effects of diet on health, which, together with well-controlled intervention studies, have informed national food-based dietary guidelines. We draw on this well-established evidence base to inform the principles of the diet, as well as its recipes.

Here we provide examples on how to apply these four pillars to inform dietary recommendations, specifically for the cases of dietary fibre and dairy.

For dietary fibre, we can conclude that:

- Humans evolved, for the most part, consuming much higher amounts of dietary fibre than what is currently recommended (evolution)

- Fibre acts as growth substrates for gut microbes, and its fermentation influences microbiome function in ways that are likely beneficial (ecology)

- Fibre improves host-microbiome interactions, for example through immune-modulatory metabolites and reduced mucus degradation (mechanisms)

- The beneficial effects of fibre are well-established in the nutrition literature, with evidence suggesting that levels higher than 40 grams/day provide greater benefits to health (nutrition)

Thus, we recommend that the majority of one’s diet is comprised of whole-plant foods to achieve dietary fibre levels of >40 grams per day.

For dairy, which has been a controversial topic in nutrition research and the history of dietary guidelines, we can conclude that:

- Humans did not consume milk, other than human milk, until a few thousand years ago. There is still a sizable portion of the global human population that does not consume dairy, and many people remain lactose intolerant. That being said, dairy was an important factor in human evolution in regions such as Europe and led to the emergence of lactase persistence as a genetic trait. There are, therefore, arguments for and against the consumption of dairy based on human evolution (evolution)

- Milk fat enriches for the genus Bilophila, a pro-inflammatory bacterium, via the induction of bile acids. This has been observed in both animal and human studies (ecology)

- Bile acids, levels of which are increased with higher levels of saturated fat intake from high-fat dairy, are transformed by the microbiome to secondary bile acids. These compounds are linked to inflammation and dysplasia (mechanisms)

- There is much research on the nutritional value of dairy, with both positive and negative effects reported. High-fat dairy is consistently discouraged in nutritional guidelines, while low- and normal-fat dairy are encouraged due to their healthier nutritive profiles (e.g., providing calcium, vitamin D, and protein) (nutrition)

Thus, we recommend a moderate intake of low- and normal-fat dairy (e.g., yogurt) while limiting high-fat dairy products such as butter, cream, and most cheeses.

The NiMe Diet Principles

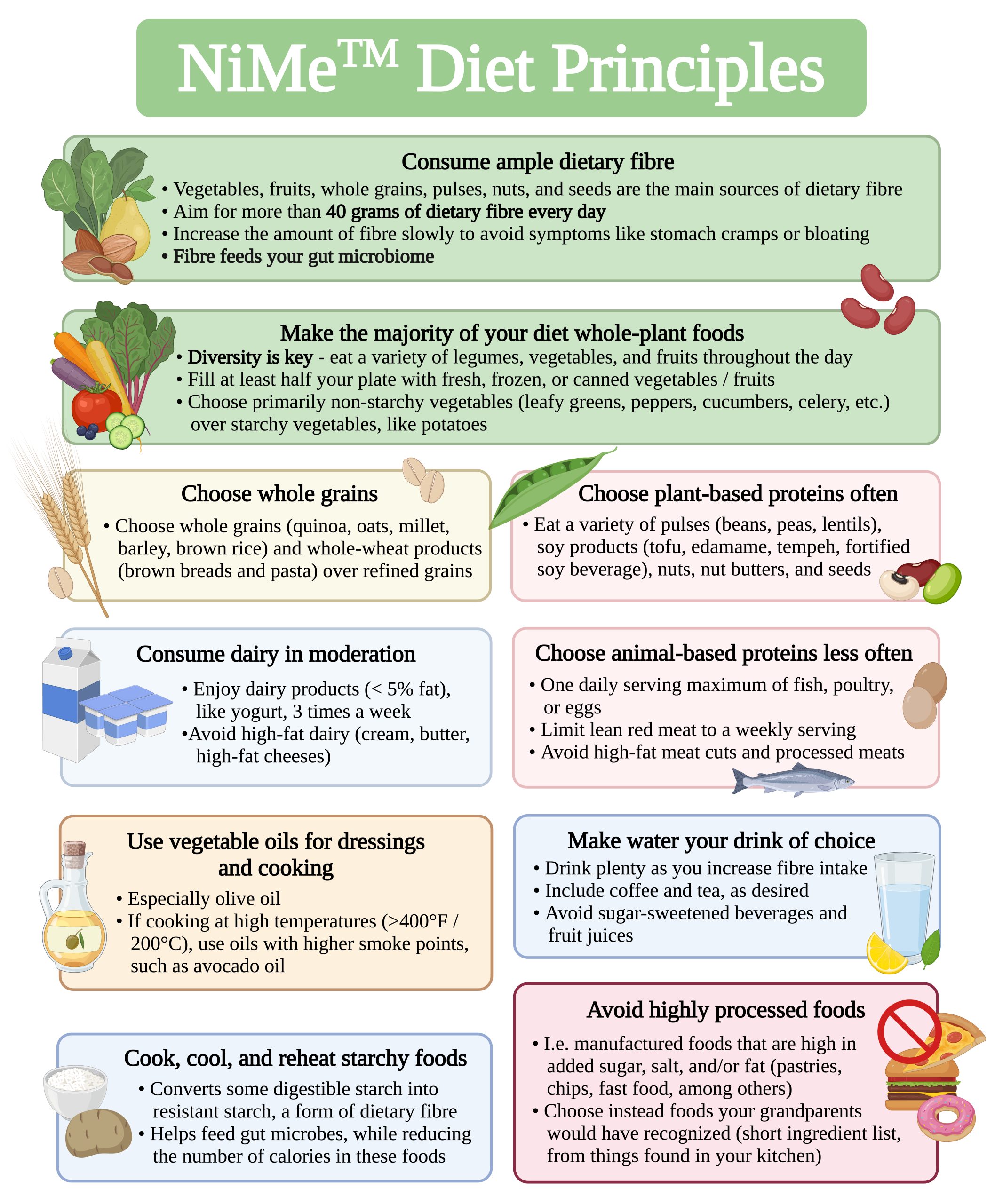

The NiMe diet is a dietary pattern, which means that it is more important to think about all the different foods one eats and how they work together holistically to benefit health, rather than focusing on specific foods or nutrients in isolation. On the infographic below, we present the plate of the NiMe diet, as well as the key principles. The focus is on what foods should be included, rather than excluded – in doing this, foods that are detrimental to health in high amounts will naturally be limited. We recommend following the principles of the NiMe diet (represented below as a plate with detailed recommendations beside it) as much as possible, recognizing that it is difficult, and likely not necessary, to do this 100% of the time.

In addition to the principles listed on the next two pages, we suggest enjoying fermented foods as desired. They are often a component of non-industrialized dietary patterns, and may provide additional health benefits due to the provision of live microbes, microbially-derived metabolites, and microbially-transformed nutrients. However, nutrition research on the health benefits of fermented foods, especially with well-controlled human intervention trials, is in its infancy, and fermented foods were not included in the clinical validation of the NiMe diet (described later on in this book). Further, the NiMe diet principles also apply to fermented foods: avoid those with high amounts of added sugar, salt, or fat, as well as fermented processed meats or fermented high-fat dairy products.

Finally, we encourage you to seek out social connection with meals (eating with family and friends). As humans, we evolved to need social connection, and food within social gatherings and cultural events represents an integral part of non-industrialized lifestyles. Daily physical activity is as well – hunter-gatherers were (and still are) active for a large portion of the day. Not only does exercise provide benefits to cardiometabolic health, muscle health, and the microbiome, but it also improves our mental health.

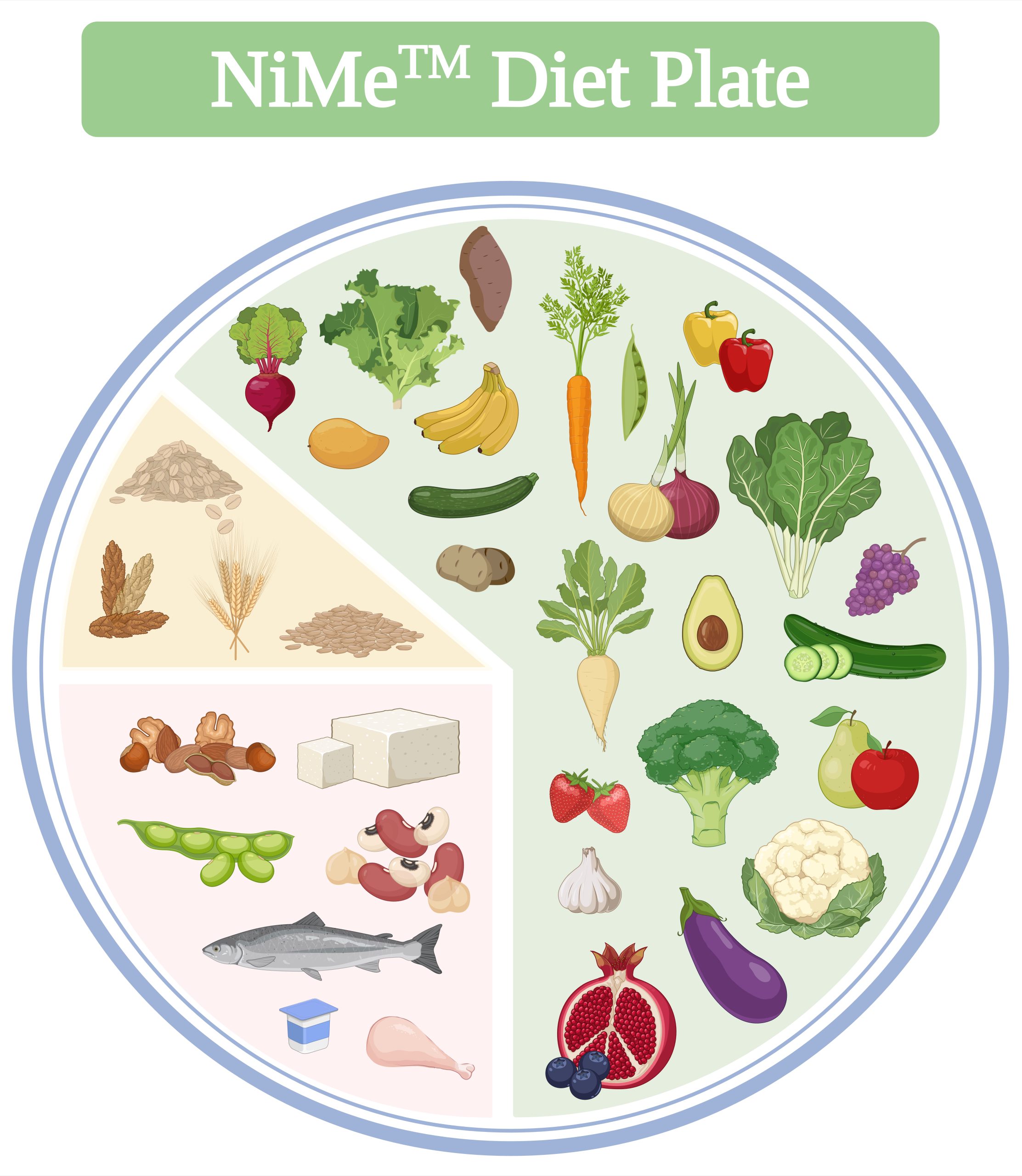

The proportions of different food groups, depicted on a plate, according to the NiMe diet. Vegetables and fruits (light green) make up the majority of one’s diet, with smaller portions included of protein foods (light red; prioritizing plant-based proteins like legumes, nuts, and seeds, with smaller amounts of animal-based proteins like fish, poultry, and yogurt) and whole grains (light yellow).

The NiMe diet principles: recommendations for which foods should be included and which should be limited or avoided.

The NiMe diet compared to other dietary patterns

There are several dietary patterns with well-established health benefits. It is important to emphasize that we are not trying to do something radically different or revolutionary with the NiMe diet. The NiMe diet agrees in large part with several contemporary dietary guidelines (e.g., Canada’s Food Guide and the Healthy Eating Plate by the Harvard School of Public Health) and dietary patterns such as the Mediterranean, Nordic, and DASH diets and, to a lesser degree, the Paleo diet. NiMe also draws inspiration from the NOVA classification of processed foods and the Planetary Health Diet. We consider such consensus in what constitutes healthy eating an advantage, as it allows individuals to choose among healthy dietary patterns which works best for them.

Nevertheless, the NiMe diet expands on other dietary frameworks, and places different points of emphasis based on the four scientific concepts described earlier. Compared to almost all dietary guidelines and other dietary patterns, the NiMe diet recommends higher fibre intakes, which can be achieved by making the majority of one’s diet vegetables, fruits, and legumes, with smaller portions of animal proteins and whole grains. This differs, for example, from the Mediterranean, Nordic, and DASH diets, which all recommend whole grains as the basis of one’s diet (i.e., several daily portions). The NiMe diet further discourages cheese (e.g., with high fat percentages), which is a constituent of a Mediterranean diet and recommended in some dietary guidelines. The NiMe diet is also distinct from the Paleo diet, which suggests avoiding grains, legumes, dairy products, and starchy vegetables altogether, and which generally encourages much higher intakes of animal proteins.