How Were the Health Effects of the NiMe Diet Validated?

Design of NiMe meal plan for research study

In 2017, Jens’ research team at the University of Alberta started a project to test the effects of a microbiome restoration strategy by prescribing a diet that shared key characteristics of non-industrialized dietary patterns, as well as introducing a bacterium (Limosilactobacillus reuteri) that was detected in the fecal samples of rural Papua New Guineans but rarely found in industrialized microbiomes.

As a registered dietitian and avid foodie, Anissa Armet was already passionate about nutrition and how it affects the gut when she joined the Walter lab. Anissa’s personal experience using a plant-based diet to successfully manage her ulcerative colitis, a form of inflammatory bowel disease, sparked her cognizance of how diet can radically impact health. In the lab, she got creative in the kitchen, creating and testing recipes inspired by Jens’ research on rural Papua New Guineans that would appeal to a person used to typical Western dishes. These recipes would eventually form the meal plan of the NiMe diet intervention.

The NiMe diet intervention was designed to include certain foods either because (i) they were consumed by rural Papua New Guineans (e.g., beans, sweet potatoes, rice, cucumber, cabbage), or (ii) contained high amounts of raffinose and stachyose – fibres that promote the growth of L. reuteri in the gut (e.g., Jerusalem artichokes, peas, onions). Aligning with the four scientific principles introduced previously (evolution, ecology, mechanism, and nutrition), the NiMe diet intervention was primarily composed of vegetables, legumes, fruits, and other whole-plant foods, resulting in daily fibre intakes of 22 grams per 1,000 calories – a daily average of around 45 grams. It contained one small serving of animal protein per day (salmon, chicken, or pork) and avoided highly processed foods. Dairy, beef, and wheat were excluded from the intervention because they are neither part of a traditional rural Papua New Guinean diet nor many other traditional diets in non-industrialized settings. These criteria allowed us to develop a meal plan that could be tested in a strictly controlled human intervention study in healthy adult participants in Canada.

Conducting a strictly controlled nutritional trial

There are several different ways to study the impact of diet in nutrition research. Some trials collect self-reported information on what people eat, while others counsel participants to follow a specific diet; nevertheless, these trial designs can provide highly unreliable results based on how accurately participants record their food intake or follow the diet of interest.

Our goal instead was to conduct a strictly controlled feeding trial. This meant preparing the NiMe diet as precisely measured, standardized meals in a metabolic kitchen (Human Nutrition Research Unit at the University of Alberta) based on a four-day, rotating menu.

Anissa cooks NiMe meals in the metabolic kitchen (Human Nutrition Research Unit at the University of Alberta). Photo credit: University of Alberta.

We then provided participants with all of their meals and snacks for a three week period.

Anissa (middle) provides meals from the NiMe diet intervention to participants in the trial (Human Nutrition Research Unit at the University of Alberta). Photo credit: University of Alberta.

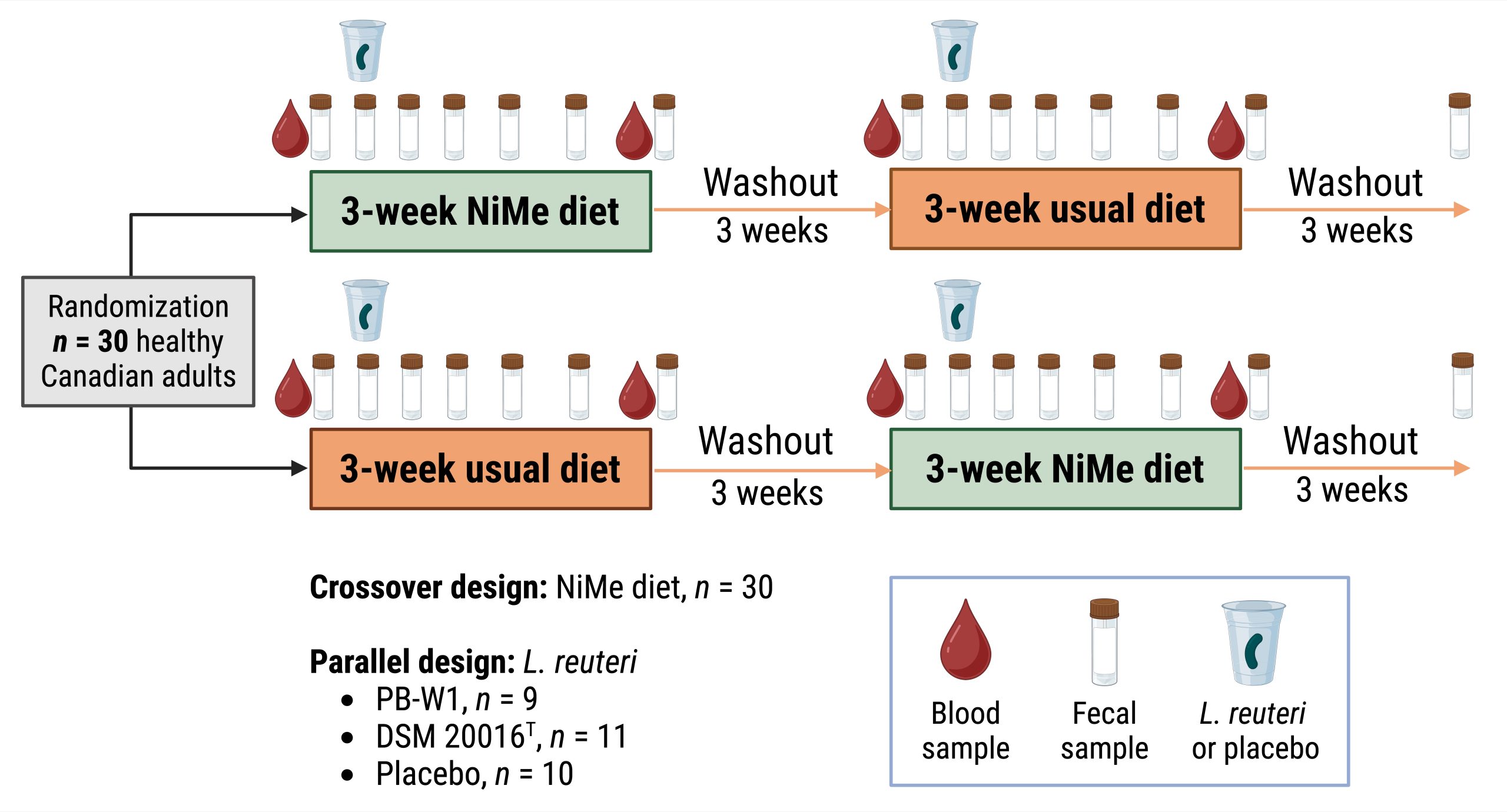

The diet intervention was conducted as a crossover trial, meaning subjects were randomized to either stay on their usual diet or consume the NiMe diet for three weeks. After a three-week washout (no intervention), subjects were crossed over to the other diet period for three weeks, followed by a final three-week washout. In a parallel-arm design, participants were also randomized to receive a single dose of either L. reuteri PB-W1™ (strain derived from rural Papua New Guinean microbiome), DSM 20016T (type strain derived from industrialized microbiome), or a placebo on the fourth day of each diet period. The two different strains of L. reuteri allowed us to test whether differences in their geographical origin impacted their ability to survive and be re-established in the gut.

Study design of the human trial that tested a microbiome restoration strategy, consisting of a ‘lost’ microbe rarely found in industrialized microbiomes – L. reuteri – alongside the NiMe diet that shared key characteristics of non-industrialized dietary patterns.

Effects of the NiMe diet on fecal microbiome

We studied the effects of the microbiome restoration strategy on the gut microbiome composition (which microbes are there) and function (what those microbes do). The NiMe diet increased persistence (how long it stayed in the gut) and survival of L. reuteri, yet the species still disappeared just two weeks after participants received it, in all but one participant. Thus, L. reuteri had no effects on any outcomes in the study.

Generally, microbial diversity is a hallmark of a healthy gut microbiome. Unexpectedly, microbiota diversity decreased when participants consumed the NiMe diet. This shift was likely driven by changes to the gut environment (e.g., making the gut more acidic through fermentation and increased production of short-chain fatty acids). Lower microbiome diversity has also been observed in vegans, suggesting that a plant-rich diet may reduce microbiome diversity, at least in the short-term.

Many of the detected changes in the fecal microbiome altered by the NiMe diet are considered beneficial. For example, the diet increased the abundance of fibre-degrading microbes that can benefit health, like Faecalibacterium, Lachnospira, and Bifidobacterium species. At the same time, it reduced pro-inflammatory microbes that can be detrimental to health, like Bilophila wadsworthia, Alistipes putredinis, and Ruminococcus torques. These decreases in pro-inflammatory microbes were likely due to reduced consumption of saturated animal fat during the NiMe diet intervention.

Effects of the NiMe diet on risk markers of chronic diseases and indicators of health

On a western diet low in dietary fibre, the gut microbiome degrades the mucus layer in the gut, which leads to inflammation. The NiMe diet prevented this pathological process, thus reducing inflammation. In addition, the diet increased beneficial bacterial metabolites in the blood, like indole-3-propionic acid, which has been shown to protect against type 2 diabetes and nerve damage.

Research also shows that low dietary fibre leads to gut microbes ramping up protein fermentation, which generates harmful byproducts that likely contribute to colon cancer. In fact, there is a worrying trend of increased colon cancer in younger people, which may be caused by recent trends toward high-protein diets. The NiMe diet increased carbohydrate fermentation at the expense of protein fermentation, and it reduced several metabolites linked to cancer, such as secondary bile acids and 8-hydroxyguanine.

We saw remarkable results, including weight loss (even though participants didn’t change their calorie intake), a drop in bad cholesterol (LDL) by 17%, decreased blood sugar by 6%, and a 14% reduction in C-reactive protein (a marker for inflammation and heart disease). Using machine learning (a form of AI), we found that these clinical benefits were linked to changes in the participants’ gut microbiomes, specifically microbiome features damaged by industrialization.

Summary of the results of the NiMe diet intervention trial:

The trial tested the effects of a microbiome restoration strategy – the NiMe diet combined with a lost microbe, Limosilactobacillus reuteri – on the gut microbiome and risk markers of chronic diseases. L. reuteri was not successfully reintroduced in all but one individual, and had no clinical effects from the one-time dose given. However, the NiMe diet significantly benefitted health (reducing body weight, blood glucose, cholesterol, and C-reactive protein), which was linked to improvements in several gut microbiome features negatively affected by industrialization. BCFAs, branched-chain fatty acids; CAZymes, carbohydrate-active enzymes; SCFAs, short-chain fatty acids.

Outlook

The findings from our research demonstrate that a dietary intervention targeted towards restoring the gut microbiome can improve indicators of health and reduce risk markers of chronic diseases. This information can help individuals improve their nutrition, as well as aid healthcare professionals and policy makers to improve dietary recommendations.

The NiMe diet offers a practical roadmap for anyone interested in improving their health with nutritious meals that feed both our human bodies and our gut microbiomes. This book includes all the recipes that were clinically validated in a human nutritional trial. We will continue to update on our research and provide additional recipes through our social media pages (Instagram, Facebook, LinkedIn, X, and TikTok).

Discover the full study here: https://www.cell.com/cell/fulltext/S0092-8674(24)01477-6