Module 5: Working with the Online Learner (Light)

The light version of this module is designed to assist you in planning the supports you will put in place for your online learners.

Unless you specifically desire our feedback, you will not need to update us of your progress or share back results with the cohort.

This light module is estimated to take you between 2-3 hours to complete but can take (significantly) longer if you cannot base your pivot on previous online teaching experiences and resources.

If once the light version is completed, you still want to delve in deeper into the topic, you can access the complete module with additional activities and resources here.

Module Content

- Orientating Students to an Online Course

- Designing for Diverse Students

- Managing Student Behaviour and Conflict

Guiding Questions

- How can I communicate to my students the fundamentals of learning in my online course, including expectations and supports for navigation and academic success?

- How can I build success in my courses to support diverse online learners with their different forms of motivation and learning preferences, personalities, and cultural backgrounds, academic knowledge and study skills, independence, and disabilities?

- How can I facilitate opportunities for all of my online students to develop core undergraduate/ graduate attributes (e.g. critical thinking, collaboration, conflict resolution, problem-solving, reflection)?

Much like you the newly turned online educator, many of your students will not have made a conscious choice to take online classes during their time in university. It is therefore to be expected that your students, now being forced to learn online, will possess varying skill sets and experience relating to managing their studies in that delivery mode. As research investigating student success has shown, learner history is an important predictor of persistence in online programs. In other words, the less exposure students have previously had to online learning, the more support they will still need to build skills in time management, self-directed learning, and navigation of unfamiliar virtual environments and technology. (Hung et al, 2010; Li et al, 2016)

Four pillars have been identified as crucial to successful student performance in online courses or programs, including an orientation at the start, online-friendly academic resources, adequate technical scaffolding, health/ well-being support, and a sense of belonging to the fully online cohort. (Roddy et al, 2017)

Being in the midst of a global crisis puts unprecedented stress on you and your students. The pivot from campus-based to online delivery at such short notice will most likely be a novel and somewhat daunting experience for you and your students, especially considering the fact that unexpected responsibilities may arise and sudden shifts in priorities might impede with your ability and that of your students to produce consistent academic work.

Video [10 mins] Student Perspective: An Invitation and a Challenge: a Student Asks us to Reimagine.

Video [10 mins] Student Perspective: An Invitation and a Challenge: a Student Asks us to Reimagine.

Lily Rose Fitzmaurice has just graduated from the University of Warwick. She was a student at the Institute for Advanced Teaching and Learning (IATL). In the following video, you can hear her speak about her reflections on being a student in general and during the Covid pandemic especially. Listening to what she would like to say to a group of educators and learners gathered together in community, might have you re-consider your own perspective on higher education today and the your role you are playing within in it.

UDL: Alternatively to viewing the video, you can read the Youtube-generated Transcript Teaching and Learning Online (Fitzmaurice) (word document).

- What questions does this video raise for you?

- What ideas or possibilities does it present?

- What aspects mentioned would you like to address in your own online courses?

Optional: If you are in this course for the cohort experience, we’d like to invite you to share your responses to the student video in our Working with the Online Learner Module Forum [new tab].

Optional: If you are in this course for the cohort experience, we’d like to invite you to share your responses to the student video in our Working with the Online Learner Module Forum [new tab].

Designing and facilitating an equitable online course includes five primary areas of consideration, all of which are integral parts in the different modules of this course (Kelly, 2019):

| Aspect | Meaning |

| Academic | Students’ preparedness for learning and readiness for online learning |

| Pedagogical | Course Organisation and design, engagement and interaction, effective teaching methods, strategies and practices |

| Psychological | Student’s feelings of social belonging and ability to express stereotype threat, as well as perceptions of course relevance and instructor compassion |

| Social | Students’ perceptions of connection versus isolation related to the course |

| Technological | Students’ ability to access and use course technologies |

Extended Resources: The Peralta Rubrics developed by Stark and Kelly details the above items and provides descriptions for practices that demonstrate equity standards within an online course: https://web.peralta.edu/de/equity-initiative/equity/

Extended Resources: The Peralta Rubrics developed by Stark and Kelly details the above items and provides descriptions for practices that demonstrate equity standards within an online course: https://web.peralta.edu/de/equity-initiative/equity/

This module will engage you in the planning of the academic, pedagogical and technological aspects by walking you through the steps required to design/ revise:

- pedagogical scaffolds,

- a course orientation,

- and accessible teaching resources.

1. Orientating Students to an Online Course

1.1 Scaffolds to Support Student Learning Online

Teaching and learning online changes some of the ways in which learners interact with content and other participants in an online course. Well-designed and facilitated online courses can offer students rich and flexible learning experiences that will not only foster academic growth but also shape the impressions learners have of learning online.

Since online instructors work in the absence of physical cues such as facial expressions, raised hands or noisy chatter in their students, you will need to thoroughly plan out the following:

- how the resources of your choice will demonstrate your expectations for learning,

- how you want to deliver your content,

- and how you will guide your students through the learning and assessment activities you are designing before the start of the course.

Instead of trying to emulate “real” classroom interactions, you can direct your focus to the deliberate design of your online course to “help your students persist by orientating them to the course environment, helping them understand expectations, and providing them with resources throughout the course.” (Stavredes, 2011, p. 85)

Having fewer means as an online instructor to directly encourage your students requires careful selection and planning of resources, methods and tools to navigate students through your chosen online learning spaces. This planning will guide them in their engagement with the academic activities and equip them to meet the goals of the course. Below you will find examples for four forms of cognitive scaffolding in online pedagogy that can “help learners enhance, augment, and extend their thinking processes, which can result in improving learners’ thinking skills as they engage in the learning activities.” (Stavredes, 2011, p. 74).

Scaffolding here refers to the design of a course to include processes that support individual learning efforts through an appropriate structure and specific tools that guide your students in their decisions:

- Procedural Scaffold: how to utilize the learning environment and its functions,

- Metacognitive Scaffold: how to analyze and approach learning tasks or problems,

- Conceptual Scaffold: how to process new information or work with information that is difficult to understand,

- Strategic Scaffold: to find the appropriate pathway among several alternatives that can best meet the diverse needs for learning.

(Hannafin et al, 1999, p. 131)

1.2 Activity Guiding the Planning of an Orientation

If you are interested in designing an orientation for your online course, you can do the suggested steps in the following learning activity. Otherwise, feel free to skip the activity and move into the next section in this module.

Orientation to an Online Course

Orientation to an Online Course

This activity has 2 steps (outlined in the presentation below).

Purpose: This activity starts off with two students talking about their learning in their online courses. You will then access examples of course orientations from fellow university instructors and consider templates to help you build your own online course orientation.

Navigation:

You can move between the steps in the presentation by accessing the slides on the bottom of the presentation below (see them numbered 1 – 4).

You can enlarge the slides for a better viewing experience by hitting the arrows on the lower right. In Slide 3, you can access the examples by clicking on the active links.

You can also type your own notes at the bottom of the Slide 3 and finally export them together with the links for reference on Slide 4.

Technology:

The presentation was created with the OER tool H5P to allow for embedding of video and exportable text. An instructor tutorial for how to create H5P activities can be found here [new tab].

Watch the brief tutorial below to see how students work with an H5P presentation by clicking on this link.

Please find attached here the Youtube-generated transcript to the video in Slide 2: Transcript for Youtube Video Learning Online from Student Perspective

Extended Resources:

Extended Resources:

As discussed above, Stavredes (2011, p. 103) produced a scaffold planning tool for the different kinds of scaffolds. To inspire your own planning of scaffolds for your online course(s), the table below contains current examples and template resources that you can open in new tabs by clicking on the respective active links.

You are free to browse as many or as few examples you would like to get your course design juices flowing. There is no task attached other than to take a look at one or some of the resources that will help your students come into your online course better prepared and be well supported throughout its duration.

| Type of Scaffolding | Subtypes | Examples |

| Procedural: Support how to navigate learning environment and engage in learning activities | I want to provide an Orientation to my online course (e.g. use a Syllabus that includes an overview and/ or create an activity to orient learners to the most essential elements in the course) |

U of L Online Courses :

3 FLOf2019 Course Orientation 4 Dr. van Heyking’s Introductory Accounting Course [self enrolment as TA] |

| External Orientation Templates

U of T Education Course Outline Kwantlen Polytechnic: 1. CMNS Delivery Plan |

||

| Quality Standards Rubric to Develop your own Orientation | ||

| I want to communicate my Expectations to the students and share campus Support Resources with them. |

Template Learning and Teaching Expectations | |

| FitFOL2020 Expectation Document | ||

| Plagiarism Statement + Toolkit | ||

| U of L Campus-Specific Student Supports | ||

| Metacognitive: Support of Study Skills (Learning Management) | I want to help my students Plan their time participation in my course and understand how the activities tie into the greater course goals. |

Course Overview (Schedule) Examples: |

| Course Road Map | ||

| FLOd2019: Unit Overview

FLOd 2019 Course Road Map CMNS 1140 Course Map on page 7 |

||

| Online Textbook: Learning to Learn Online | ||

| I want to help my students in Monitoring and Documenting their progress. |

Templates, Worksheets, worked examples |

|

| Unit Checklist | ||

| Time logs (Managing Time and Motivation) | ||

| Note-taking tools (1 + 2) for lectures and readings | ||

| I want to involve my students in the processes of Evaluating their own learning and my online course. |

Grading rubrics, scoring guides with self-evaluation strategies | |

| Self-reflections | ||

| Student Feedback at specific points during term: FitFOL2020 Exit Feedback | ||

| Conceptual – Support for Information Literacy and Information Management | I want to support my students in the Processing and Application of the course information. | Definitions |

| Chunking Information/ Assessments | ||

| Study Guides | ||

| Outline | ||

| Advance Organizers

Graphic Organizers – diagrams, concept maps, etc. |

||

| Strategic – Create alternative learning pathways | I want to make sure all students in my course will Engage with the course content. | Alternative explanations |

| Probing Questions | ||

| Hints | ||

| Worked examples | ||

| Supplementary resources | ||

| Expert advise | ||

| Definitions | ||

| Chunking Information/ Assessments | ||

| Alternative explanations |

1. 3 Self-evaluate Your Understanding of Online Orientations and Learning Scaffolds

The following short quiz is a brief check for your readiness to provide your learners with assistance in specific place in your course to ensure they understand the expectations and can prepare for their success. There are 3 questions, the results of which are for your own reference and will not be recorded.

2. Designing for Diverse Students

2.1 Inclusive Course Design

To plan for a facilitation of engagement, equity and fairness, you will need to spend some time thinking about the individual learners in your courses to determine how to best match their learning needs with your teaching intentions and remove potential accessibility hurdles. To support the full range of human diversity with respect to ability, language, culture, gender, age, and other forms of human difference, you will need to pay special attention to the following aspects of inclusive course design for learning:

- the online learning environment,

- the diversity in and different formats for resources you will curate, adapt, and/or create,

- the choices you allow students to make relating to content, learning and assessment so they can stay invested and engaged,

- the various levels of challenge in tasks and content,

- your availability and willingness to respond to students’ question and ideas,

- the tips you deliver how to stay motivated,

- the connections you draw between the information and the real world applications,

- the feedback you provide on students’ progress.

Extended Resources: The BCcampus has recently funded an Equity in Education: Removing Barriers to Online Learning research research project conducted by Andrea Sator and Heather Williams, ABLE Research Consultants, which led to the production of the following series of infographs listing barriers to learning along with evidence-based strategies to overcome them:

Extended Resources: The BCcampus has recently funded an Equity in Education: Removing Barriers to Online Learning research research project conducted by Andrea Sator and Heather Williams, ABLE Research Consultants, which led to the production of the following series of infographs listing barriers to learning along with evidence-based strategies to overcome them:

2.2 Accessibility of Course Resources

When you choose or create teaching materials for your courses, you might want to ensure that all your students can easily access and use those resources. Accessible content meets the requirements of the Alberta Human Rights Act, which “has as its objective the amelioration of the conditions of disadvantaged persons or classes of disadvantaged persons, including those who are disadvantaged because of their race, religious beliefs, colour, gender, gender identity, gender expression, physical disability, mental disability, age, ancestry, place of origin, marital status, source of income, family status or sexual orientation.”

Content authors must ensure that their e-learning content is presented in multiple formats and, therefore, accessible through multiple senses. For people who are blind, visual materials require an alternative, typically in the form of text readable by screen readers. While an audio version of visual content (such as an MP3 audio file that describes a complex image) could be used as an alternative, chances are the audio will interfere with the screen reader output. Text alternatives, on the other hand, are easily adapted or even simplified, read aloud by a screen reader, turned into Braille to be output through a Braille display, or translated into other languages.

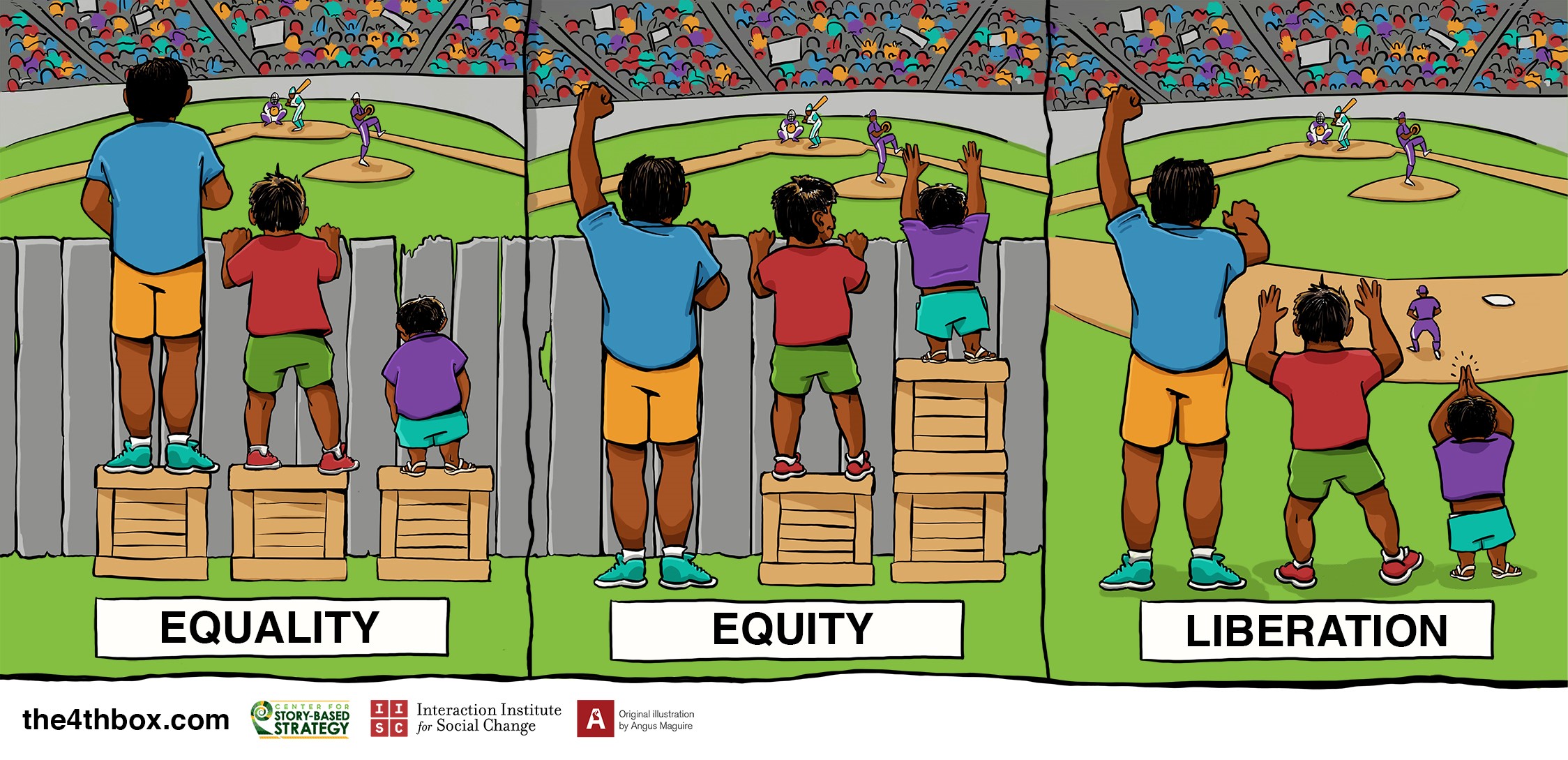

The graph above is used to show that there are multiple levels on which access to learning can be impeded, not only pertaining to the resources you create yourself. The online learning environments and content created by others come with their own in-built design features, which cannot easily be altered. However, there are a number of things that you can do ensure that the course resources you use are accessible or come with workarounds that allow all students equal learning opportunities. In the following activity, you will focus on learning challenges and ways to overcome those.

The graph above is used to show that there are multiple levels on which access to learning can be impeded, not only pertaining to the resources you create yourself. The online learning environments and content created by others come with their own in-built design features, which cannot easily be altered. However, there are a number of things that you can do ensure that the course resources you use are accessible or come with workarounds that allow all students equal learning opportunities. In the following activity, you will focus on learning challenges and ways to overcome those.

Activity 2: Personas – How to Meet Accessibility Standards

Activity 2: Personas – How to Meet Accessibility Standards

This activity has 5 steps (outlined below).

Purpose: This activity introduces specific (often undocumented) learning challenges students can face along with different types of hardware and software that they might use for accommodations.

Navigation: You can access the information in the BCcampus Open Ed Accessibility Toolkit by simply clicking on the link below next to Step 1.

Technology: The Accessibility Toolkit in Step 1 is an open textbook created with the Pressbooks Software. It is being hosted in the BC Campus Open Textbook repository, where it can be accessed freely in digital format or downloaded for offline use. The Persona Card in Step 2 is available for viewing and downloading from a Google Drive link.

STEP 1: Read the following sections in the Accessibility Toolkit:

| Sections | Links |

| Personas | https://opentextbc.ca/accessibilitytoolkit/chapter/using-personas/ |

| Best Practices | https://opentextbc.ca/accessibilitytoolkit/part/best-practices/ |

STEP 2: Do you now know which learner types need what format for resources? Briefly check your knowledge here by dragging the appropriate content type on to the matching persona below.

STEP 3: Open the following Persona Card Document by clicking on this link: http://goo.gl/m1Fp6

Now take a few minutes to think about 1-3 potential learners in your course. Fill in the missing blanks for a more holistic picture of the diversity of learners in your course.

Download a copy in a format of your choice (.doc; odt; txt, or other) if you would like to retain a document for future reference. Downloading is possible through the FILE tab on the upper left.

STEP 4: Based on the Best Practices introduced to you in STEP 1, you will now evaluate the accessibility of this Module Option 2 Page.

Take a closer look at all of the parts on this page with all its elements (headers, pictures, tables, links, etc.) before you answer the following five quiz questions:

Please note: Should you, contrary to the test results, encounter accessibility issues with this page, you can report them to us here [new tab directing you to UofL Qualtrics mask]

STEP 5: Implement accessibility recommendations into the design of your own online course.

Now refer to back to your online course in preparation to answer the following two questions:

- What proactive practices outlined in the STEPs 1-3 can you apply to make your course more accessible this first time round?

- Which practices are long-term projects and will have to wait for future iterations?

Additional Resources:

- Accessible Assessments: The Hitch-hiker’s Guide to Alternative Assessment [new tab] (Gordon, 2020, p. 4-10)

- U of L Accessibility Toolkit for Educators [new tab]

- Diversity and Equity in Learning created by Dr. Cheryl Richardson and Sophie le Blanc for the University of Delaware Center for Teaching and Assessment of Learning October 2015 [new tab]

2.3 Represent Diversity in Content and Practices

By choosing specific content and pedagogical approaches, you signal to your students what stance you are taking to teaching diverse groups of learners.

If you want to take a moment here to reflect on your course to be transformed for online delivery and ask yourself in how far your content and the teaching methods

The following excerpt from the ASCILITE technology-enhanced learning accreditation scheme (standard 7.3) provides quality markers for online courses at universities in higher ed courses in Australasian countries and may be a useful instrument guiding your content choices to reflect diversity:

There are a number of ways in which you as the online course instructor create safe, equitable and inclusive courses that are inviting to all your learners:

- Assume students are diverse in ways that you cannot see –that might be related to race, national origin, socioeconomic status, ethnicity, physical and neuro-disabilities, sexual orientation, spiritual beliefs, or many other possibilities.

- Be explicit about your assessment criteria and how they relate to learning goals, and share successful examples.

- Vary and offer rationale for assessment types.

- Examine and consider revising choices for scholarly articles and other resources, guest speakers, etc. to include a diverse range of information and representation.

3. Managing Student Behaviour and Conflict

No different from traditional on-campus classes, online courses welcome a broad range of individual learners who, with their unique set of personality traits, desires for learning, life-changing events in their biographies, and high hopes for future advancement, will inevitably shape the dynamics of your course(s) through the interactions with you and her/ his/ zer/ their peers.

You can place bets on the fact that there will be students who keep quiet and tend to only hesitatingly take part in the course conversations. At the same time, you can expect their exact opposites – the take-charge students or the ‘noisy’ ones as defined by Ko and Rossen (2010, p. 343). There will likely be students who disengage from your course for different reasons opposite to those who will challenge your knowledge or your authority. No doubt, these difficult student behaviours can make online teaching difficult at times.

It is therefore very important to know which specific factors cause or amplify difficult behaviours of students in online environments. An awareness for those factors is crucial as it guides your course design to include proactive strategies that can help prevent behavioural issues from arising. It also equips you with management methods that you can utilize to if you need resolve conflict with individual students or with dissonant student groups after all.

3.1 Managing Difficult Students

Students who demonstrate behavioural issues are often unclear about the course requirements or have not yet build proficient skill levels to learn independently online without some extra help coming from you. The difficulties students have and exhibit in their behaviour can thus take many forms – from an inability to adjust to new technologies, to domination or sidetracking of conversations, to a lack of participation and scapegoating others for the own lack in sufficient academic progress. As those difficulties might show up with a delay in an online environment, you will need to become able to read signs as early as they appear and know which strategies to apply for different types of behaviour issues, some of which we will examine with the following activity.

Activity 3: Management Strategies for Different Learner Types

Activity 3: Management Strategies for Different Learner Types

This activity has 2 steps (outlined below).

Purpose: This activity introduces different learner types, describes their impact on the course dynamics and provides strategies to effectively deal with difficult behaviour.

Navigation: You will navigate between this chapter and the spaces where you can access the necessary information and collaborate with your peers.

Technology: The technology used for this activity include Pressbooks and Youtube

STEP 1: Choose your preferred way to learn about specific learner types, behavioural issues and suggested strategies below. Both formats present the same information, but in different ways (viewing/ listening a video presentation versus reading a book chapter).

|

|

| Read the book chapter excerpt in Ko, S. & Rossen, S. (2010). Online Teaching. A Practical Guide. Taylor and Francis. Read Chapter 12. Classroom Management. Special Issues, pp. 339 – 356.

Available as a fair dealings copy on Moodle [new tab] |

Watch the video presentation by Mandernach, J. (2013, October 22). Dealing with Difficult Students in the Online Classroom. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1nTStCJBECw [new tab]

Pdf of powerpoint available from https://www.uttyler.edu/cetl/files/Difficultstudents.pdf [new tab] |

STEP 2: Direct your focus to answering the following two questions while accessing the necessary information.

- What are some common behavioural issues in specific types of online learners?

- What strategies can be applied to manage those behavioural problems?

3.2 Strategies for Working with Online Course Dynamics

Generally, experienced online instructors agree with the statement made by Ko and Rossen (2010) that:

[…] most problems can be averted by the skillful management of student expectations such as we have outlined in earlier chapters – the comprehensive syllabus, clearly written assignment instructions, protocols for communication, code of conduct and clearly stated policies and criteria for grading as well as instructor responsiveness, are all ways to ensure that students understand how to do their best in your online course. (p. 343)

Pratt and Palloff (2003, p. 185-6) have derived a series of tips out of stage theory and their own experience teaching online, which are listed in the accordion below. You can click on each of its titles to reveal further explanations for each of the points.

Note: For a more in-depth discussion of the topic as well as additional learning activities and resources, you can refer to the comprehensive chapter: Working with the Online Learner and the three distinct module options presented with it here.

In education, scaffolding refers to a variety of instructional techniques used to move students progressively toward stronger understanding and, ultimately, greater independence in the learning process.

Fit for Online Learning Course run 3 x in 2020

Facilitating Learning Online was a 10 weeks online course delivered for U of L faculty in the Fall of 2019.

Facilitating Learning Online: Design an Online Course was a 5-week online faculty development course run in the Spring of 2019.