5.4 Principles of Nonverbal Communication

eCampusOntario

Learning Outcomes

- Give examples of nonverbal communication and describe its role in the communication process.

- Explain the principles of nonverbal communication.

- Describe the similarities and differences among eight general types of nonverbal communication.

- Demonstrate how to use movement to increase the effectiveness of your message.

- Demonstrate three ways to improve nonverbal communication.

Dhavit is getting some feedback from his team that facilitation participants think he is angry or upset during question and answer sessions. One of his colleague has noticed that Dhavit’s arms are often crossed when concerns are being raised, and his facial expression sometimes indicates that he feels threatened by criticisms of organizational systems. As you read through this chapter, consider what might be happening and how Dhavit might adjust his facial expressions and body language as part of dialogue with staff members.

Dhavit is getting some feedback from his team that facilitation participants think he is angry or upset during question and answer sessions. One of his colleague has noticed that Dhavit’s arms are often crossed when concerns are being raised, and his facial expression sometimes indicates that he feels threatened by criticisms of organizational systems. As you read through this chapter, consider what might be happening and how Dhavit might adjust his facial expressions and body language as part of dialogue with staff members.

Nonverbal communication has a distinct history and serves separate evolutionary functions from verbal communication. For example, nonverbal communication is primarily biologically based while verbal communication is primarily culturally based. This is evidenced by the fact that some nonverbal communication has the same meaning across cultures while no verbal communication systems share that same universal recognizability (Andersen, 1999). Nonverbal communication also evolved earlier than verbal communication and served an early and important survival function that helped humans later develop verbal communication. While some of our nonverbal communication abilities, like our sense of smell, lost strength as our verbal capacities increased, other abilities like paralanguage and movement have grown alongside verbal complexity. The fact that nonverbal communication is processed by an older part of our brain makes it more instinctual and involuntary than verbal communication.

Consider the Impact of Body Language

Begin this chapter by watching the following 3 minute video from body language expert Mark Bowden to extend your learning about nonverbal communication.

Body Language

Nonverbal Communication Is Fluid

Chances are you have had many experiences where words were misunderstood, or where the meaning of words was unclear. When it comes to nonverbal communication, meaning is even harder to discern. You can sometimes tell what people are communicating through their nonverbal communication, but there is no foolproof “dictionary” of how to interpret nonverbal messages.

Nonverbal communication is the process of conveying a message without the use of words. It can include gestures and facial expressions, tone of voice, timing, posture and where you stand as you communicate. It can help or hinder the clear understanding of your message, but it doesn’t reveal (and can even mask) what you are really thinking. Nonverbal communication is far from simple, and its complexity makes your study and your understanding a worthy but challenging goal.

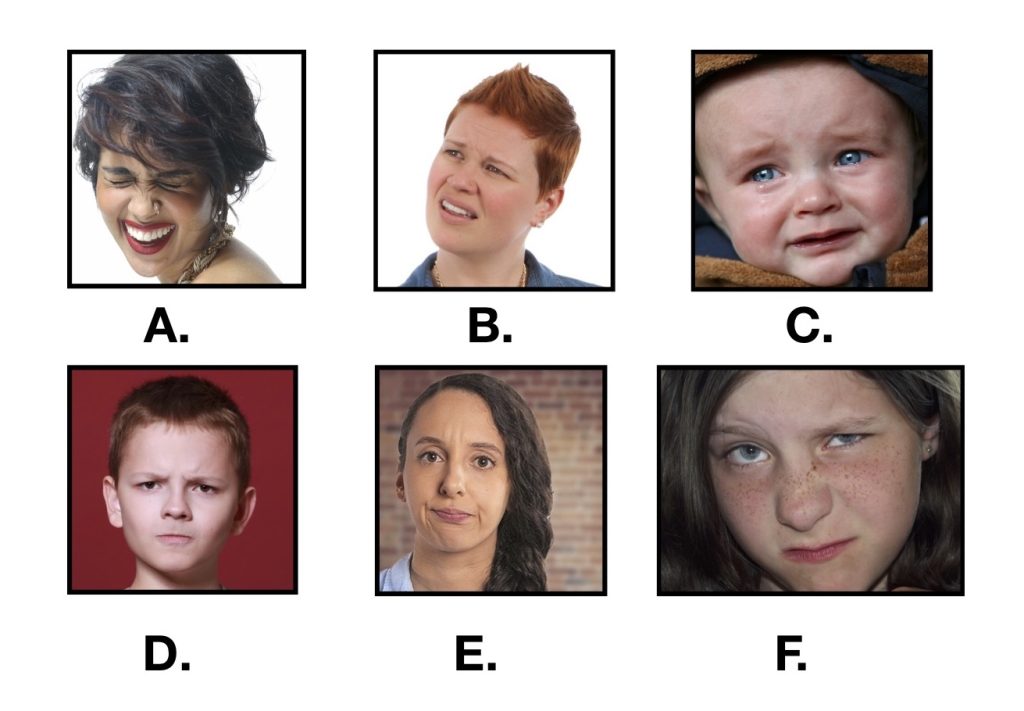

Nonverbal communication involves the entire body, the space it occupies and dominates, the time it interacts, and not only what is not said, but how it is not said. Confused? Try to focus on just one element of nonverbal communication and it will soon get lost among all the other stimuli. Consider one element, facial expressions. What do they mean without the extra context of chin position, or eyebrows to flag interest or signal a threat? Nonverbal action flows almost seamlessly from one movement to the next, making it a challenge to interpret one element, or even a series of elements. How well can you correctly identify the feelings behind facial expressions?

The following series of images show people with a variety of facial expressions, what does each one represent?

Images source: Pixabay, Public Domain – the answer key is at the end of this section.

You may perceive time as linear, flowing along in a straight line. You do one task, you’re doing another task now, and you are planning on doing something else all the time. Sometimes you place more emphasis on the future, or the past, forgetting that you are actually living in the present moment whether you focus on “the now” or not. Nonverbal communication is always in motion, as long as you are, and is never the same twice.

Nonverbal communication is irreversible. In written communication, you can write a clarification, correction, or retraction. While it never makes the original statement go completely away, it does allow for correction. Unlike written communication, oral communication may allow “do-overs” on the spot: you can explain and restate, hoping to clarify your point. In your experience, you’ve likely said something you would give anything to take back, and you’ve learned the hard way that you can’t. Oral communication, like written communication, allows for some correction, but it still doesn’t erase the original message or its impact. Nonverbal communication takes it one step further. You can’t separate one nonverbal action from the context of all the other verbal and nonverbal communication acts, and you can’t take it back.

In a speech, nonverbal communication is continuous in the sense that it is always occurring, and because it is so fluid, it can be hard to determine where one nonverbal message starts and another stops. Words can be easily identified and isolated, but if you try to single out a speaker’s gestures, smile, or stance without looking at how they all come together in context, you may miss the point and draw the wrong conclusion. You need to be conscious of this aspect of public speaking because, to quote an old saying, “Actions speak louder than words.” This is true in the sense that people often pay more attention to your nonverbal expressions more than your words. As a result, nonverbal communication is a powerful way to contribute to (or detract from) your success in communicating your message to the audience.

Answer Key for Facial Recognition Activity – F: Disgusted; E: Annoyed; D: Angry; C: Sad; B: Confused; A: Joyful

Nonverbal Communication Is Fast

Nonverbal communication gives your thoughts and feelings away before you are even aware of what you are thinking or how you feel. People may see and hear more than you ever anticipated. Your nonverbal communication includes both intentional and unintentional messages, but since it all happens so fast, the unintentional ones can contradict what you know you are supposed to say or how you are supposed to react.

Nonverbal Communication Can Add to or Replace Verbal Communication

People tend to pay more attention to how you say something rather than what you actually say. You communicate nonverbally more than you engage in verbal communication, and often use nonverbal expressions to add to, or even replace, words you might otherwise say.

You use a nonverbal gesture called an illustrator to communicate your message effectively and reinforce your point. For example, you might use hand gestures to indicate the size or shape of an object to someone. Think about how you gesture when having a phone conversation, even though the other person can’t see you, there’s an important unconscious element to nonverbal communication.

Unlike gestures, emblems are gestures that have a specific agreed-on meaning, like when someone raises their thumb to indicate agreement. Many cultures have a variety of different nonverbal emblems.

In addition to illustrators or emblematic nonverbal communication, you also use regulators. “Regulators are nonverbal messages which control, maintain or discourage interaction” (McLean, 2003). For example, if someone is telling you a message that is confusing or upsetting, you may hold up your hand, a commonly recognized regulator that asks the speaker to stop talking.

Let’s say you are in a meeting presenting a speech that introduces your company’s latest product. If your audience members nod their heads in agreement on important points and maintain good eye contact, it is a good sign. Nonverbally, they are using regulators encouraging you to continue with your presentation. In contrast, if they look away, tap their feet, and begin drawing in the margins of their notebook, these are regulators suggesting that you better think of a way to regain their interest or else wrap up your presentation quickly.

“Affect displays are nonverbal communication that express emotions or feelings” (McLean, 2003). An affect display that might accompany holding up your hand for silence would be to frown and shake your head from side to side. When you and a colleague are at a restaurant, smiling and waving at coworkers as they arrive lets them know where you are seated and welcomes them.

Figure 5.4.1. Matthew – I Hate Bad Hair Days – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

“Adaptors are displays of nonverbal communication that help you adapt to your environment and each context, helping you feel comfortable and secure” (McLean, 2003). A self-adaptor involves you meeting your need for security, by playing with your hair for example, by adapting something about yourself in way for which it was not designed or for no apparent purpose. Combing your hair would be an example of a purposeful action, unlike a self-adaptive behavior.

An object-adaptor involves the use of an object in a way for which it was not designed. You may see audience members tapping their pencils, chewing on them, or playing with them, while ignoring you and your presentation. This is an example of an object-adaptor that communicates a lack of engagement or enthusiasm for your speech.

Intentional nonverbal communication can complement, repeat, replace, mask, or contradict what we say. When a friend invites you to join them for a meal, you may say “Yeah” and nod, complementing and repeating the message. You could have simply nodded, effectively replacing the “yes” with a nonverbal response. You could also have decided to say no, but did not want to hurt your friend’s feelings. Shaking your head “no” while pointing to your watch, communicating work and time issues, may mask your real thoughts or feelings. Masking involves the substitution of appropriate nonverbal communication for potentially negative nonverbal communication you may want to display (McLean, 2003).

Finally, nonverbal messages that conflict with verbal communication can confuse the listener. Table 5.4.2 below summarizes these concepts.

Table 5.4.2 – Some Nonverbal Expressions

|

Term |

Definition |

|

Adaptors |

Help us feel comfortable or indicate emotions or moods |

|

Affect Displays |

Express emotions or feelings |

|

Complementing |

Reinforcing verbal communication |

|

Contradicting |

Contradicting verbal communication |

|

Emblems |

Nonverbal gestures that carry a specific meaning, and can replace or reinforce words |

|

Illustrators |

Reinforce a verbal message |

|

Masking |

Substituting more appropriate displays for less appropriate displays |

|

Object-adaptors |

Using an object for a purpose other than its intended design |

|

Regulators |

Control, encourage or discourage interaction |

|

Repeating |

Repeating verbal communication |

|

Replacing |

Replacing verbal communication |

|

Self-adaptors |

Adapting something about yourself in a way for which it was not designed or for no apparent purpose |

Nonverbal Communication Is Universal

Consider the many contexts in which interaction occurs during your day. In the morning, at work, after work, at home, with friends, or with family. Now consider the differences in nonverbal communication across these many contexts. When you are at work, do you jump up and down and say whatever you want? Why or why not? You may not engage in that behavior because of expectations at work, but the fact remains that from the moment you wake until you sleep, you are surrounded by nonverbal communication.

If you had been born in a different country, to different parents, and perhaps as a member of the opposite sex, your whole world would be quite different. Yet nonverbal communication would remain fairly consistent. It may not look exactly the same, or get used in exactly the same way, but it will still be nonverbal with all of its many functions and displays.

Nonverbal Communication Is Confusing and Contextual

Nonverbal communication can be confusing. You need contextual clues to help you understand, or begin to understand, what a movement, gesture (or lack of gestures) means. Then you have to figure it all out based on your prior knowledge (or lack thereof) of the person and hope to get it right. Talk about a challenge! Nonverbal communication is everywhere, and you and everyone else uses it, but that doesn’t make it simple or independent of when, where, why, or how you communicate.

Nonverbal Communication Can Be Intentional or Unintentional

Suppose you are working as a salesclerk in a retail store, and a customer communicates frustration to you. Will the nonverbal aspects of your response be intentional or unintentional? Your job is to be pleasant and courteous at all times, yet your wrinkled eyebrows or wide eyes may have been unintentional. They clearly communicate your negative feelings at that moment. Restating your wish to be helpful and displaying nonverbal gestures may communicate “no big deal,” but the stress of the moment is still “written” on your face.

Can you tell when people are intentionally or unintentionally communicating nonverbally? Ask ten people this question and compare their responses. You may be surprised. It is clearly a challenge to understand nonverbal communication in action. You may assign intentional motives to nonverbal communication when in fact their display is unintentional, and often hard to interpret.

Nonverbal Messages Communicate Feelings and Attitudes

Albert Mehrabian asserts that we rarely communicate emotional messages through the spoken word. According to Mehrabian, 93 percent of the time we communicate our emotions nonverbally, with at least 55 percent of these nonverbal cues associated with facial gestures. Vocal cues, body position and movement, and normative space between speaker and receiver can also be clues to feelings and attitudes (Mehrabian, 1972).

Is your first emotional response always an accurate and true representation of your feelings and attitudes, or does your emotional response change across time? You are changing all the time, and sometimes a moment of frustration or a flash of anger can signal to the receiver a feeling or emotion that existed for a moment, but has since passed. Their response to your communication will be based on that perception, even though you might already be over the issue.

Nonverbal Communication Is Key in the Speaker/Audience Relationship

When you first see another person, before either of you says a word, you are already reading nonverbal signals. Within the first few seconds you have made judgments about the other based on what they wear, their physical characteristics, even their posture. Are these judgments accurate? That is hard to know without context, but it is clear that nonverbal communication affects first impressions, for better or worse.

When a speaker and an audience first meet, nonverbal communication in terms of space, dress, and even personal characteristics can contribute to assumed expectations. The expectations might not be accurate or even fair, but it is important to recognize that they will be present. There is truth in the saying, “You never get a second chance to make a first impression.” Since first impressions are quick and fragile, your attention to aspects you can control, both verbal and nonverbal, will help contribute to the first step of forming a relationship with your audience. Your eye contact with audience members, use of space, and degree of formality will continue to contribute to that relationship.

As a speaker, your nonverbal communication is part of the message and can contribute to, or detract from, your overall goals. By being aware of that physical communication, and practicing with a live audience, you can learn to be more aware and in control.

Read the following 4-page PDF on how to dress for success “First Impressions: A Study of Nonverbal Communication” (Latha, 2014)

To summarize, nonverbal communication is the process of conveying a message without the use of words; it relates to the dynamic process of communication, the perception process and listening, and verbal communication.

Nonverbal communication is fluid and fast, universal, confusing, and contextual. It can add to or replace verbal communication and can be intentional or unintentional. Nonverbal communication communicates feelings and attitudes, and people tend to believe nonverbal messages more than verbal ones.