5.1 Principles of Verbal Communication

eCampusOntario

Learning Objectives

- Identify the rules and complexities of verbal communication.

- Comprehend the concept of abstraction in language and its implications on communication.

Verbal communication is based on several basic principles. In this section, you’ll examine each principle and explore how it influences everyday communication. Whether it’s a simple conversation with a coworker or a formal sales presentation to a board of directors, these principles apply to all contexts of communication.

Language Has Rules

As mentioned earlier in this chapter, language is a system of symbols, words, and/or gestures used to communicate meaning.

The words themselves have meaning within their specific context or language community. Words only carry meaning if you know the understood meaning and have a grasp of their context to interpret them correctly.

Three types of rules govern or control your use of words.

Syntactic Rules – govern the order of words in a sentence.

Semantic Rules – govern the meaning of words and how to interpret them (Martinich, 1996).

Contextual Rules – govern meaning and word choice according to context and social custom.

Consider the example of a traffic light as follows:

Semantics – Green means Go, and Red means Stop

Syntax – Green is on the bottom, yellow in the middle, and red on top.

Even when you follow these linguistic rules, miscommunication is possible. Your cultural context or community may hold different meanings for the words used – different from those intended by the source communicator. Words attempt to represent the ideas you want to communicate, but factors beyond your control sometimes limit them. Words often require you to negotiate meaning or to explain what you mean in more than one way in order to create a common vocabulary. You may need to state a word, define it, and provide an example in order to come to an understanding with your audience about the meaning of your message.

As discussed previously, words themselves do not have any inherent meaning. Humans give meaning to them, and their meanings change over time. The arbitrary symbols, including letters, numbers, and punctuation marks, stand for concepts in your experience. You have to negotiate the meaning of the word “home” and define it through visual images or dialogue in order to communicate with your audience.

Words have two types of meanings: denotative and connotative.

Denotative – The common meaning often found in the dictionary.

Connotative – Meaning not found in the dictionary but in the community of users itself. It can involve an emotional association with a word, positive or negative, and can be individual or collective but is not universal.

Effective communication becomes a more distinct possibility with a common vocabulary in both denotative and connotative terms. But what if you have to transfer meaning from one vocabulary to another? That is essentially what you are doing when you translate a message. For example, after bringing a U.S. campaign overseas, HSBC Bank was forced to rebrand its entire global private banking operations. In 2009, the worldwide bank spent millions of dollars to scrap its 5-year-old “Assume Nothing” campaign. Problems arose when the message was brought overseas, translated in many countries as “Do Nothing.” In the end, the bank spent $10 million to change its tagline to “The world’s private bank,” which has a much friendlier translation.

Read the following article for a few more examples of organizational messaging challenges: International Marketing Fails

Language is Abstract

Words represent aspects of our human environment and can play an important role in that environment. They may describe an important idea or concept, but labelling and invoking a word simplifies and distorts your concept of the thing itself. This ability to simplify concepts makes it easier to communicate but sometimes makes you lose track of the specific meaning you are trying to convey through abstraction.

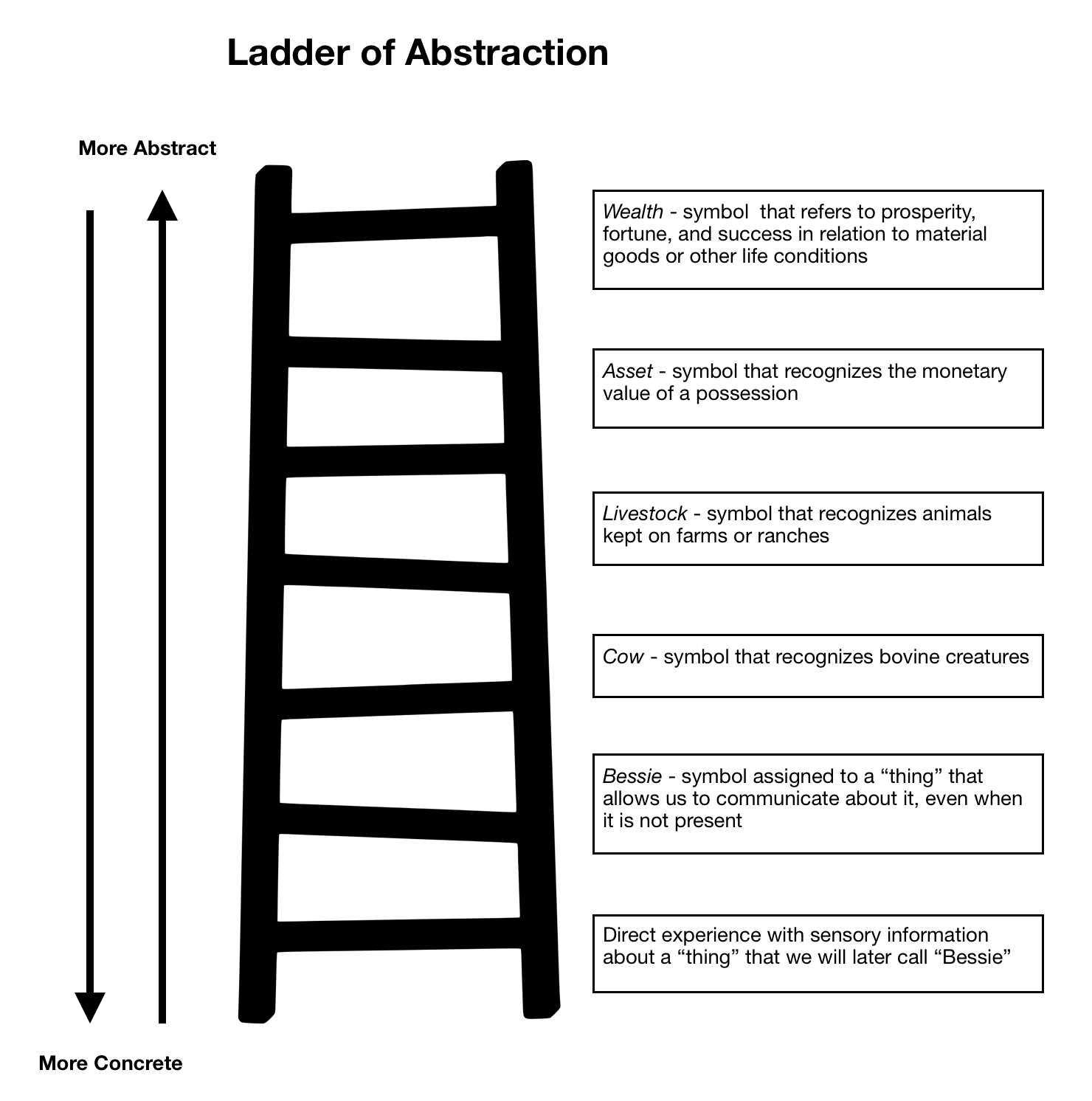

The ladder of abstraction is a model used to illustrate how language can range from concrete to abstract. If you follow a concept up the ladder of abstraction, more and more of the “essence” of the original object is lost or left out, which leaves more room for interpretation, which can lead to misunderstanding. This process of abstracting, of leaving things out, allows you to communicate more effectively because it serves as a shorthand that keeps you from having a completely unmanageable language filled with millions of words—each referring to one specific thing (Hayakawa & Hayakawa, 1990). But it requires you to use context and often other words to generate shared meaning.

Some words are more directly related to a concept or idea than others. If you were asked to go and take a picture of a book, it might seem like a simple task. If you were asked to go and take a picture of “work,” you’d be puzzled because work is an abstract word that was developed to refer to any number of possibilities from writing a book to repairing an air conditioner to fertilizing an organic garden. You could take a picture of any of those things, but you would be challenged to take a picture of “work.”

Consider the example of a cow.

If you were in a barn with this cow, you would be experiencing stimuli coming in through your senses. You would hear the cow, likely smell the cow, and be able to touch the cow. You would perceive the actual ‘thing,’ which is the ‘cow’ in front of you. This would be considered concrete; it would be unmediated, meaning it was the moment of experience. As represented in Figure 5.1.2 below, the ladder of abstraction begins to move away from experience to language and description.

Figure 5.1.2. The Ladder of Abstraction. A ladder depicting increasing abstraction of observation and language (Hayakawa & Hayakawa, 1990).

As you move up a level on the ladder of abstraction, you might give your experience a name — you are looking at ‘Bessie.’ So now, instead of the direct experience with the ‘thing’ in front of you, you have given the thing a name, which takes you one step away from the direct experience toward the use of a more abstract symbol. Now you can talk and think about Bessie even when you aren’t directly experiencing her.

At the next level, the word cow now lumps Bessie in with other bovine creatures that share similar characteristics. As you go up the ladder, the cow becomes livestock, livestock becomes an asset, and then an asset becomes wealth.

Note that it becomes increasingly difficult to define the meaning of the symbol as you go up the ladder and how with each step, you lose more of the characteristics of the original concrete experience.

Language Organizes and Classifies Reality

Humans use language to create and express a sense of order. You often group words that represent concepts by their physical proximity or their similarity to one another. For example, in biology, animals with similar traits are classified together. An ostrich may be said to be related to an emu and a nandu, but you wouldn’t group an ostrich with an elephant or a salamander. Your ability to organize is useful but artificial. The systems of organization you use are not part of the natural world but an expression of your views about the natural world.

What is a doctor? A nurse? A teacher? If a male came to mind in the case of the word ‘doctor’ and a female came to mind in reference to ‘nurse’ or ‘teacher’, then your habits of mind include a gender bias. In many cultures, there was a time when gender stereotypes were more than just stereotypes; they were the general rule, the social custom, the norm. But now, in many places, this is no longer true. More and more men are training to serve as nurses. In 2017, for example, data from the Canadian Medical Association (CMA) indicated that 41% of practising physicians in Canada were women (Canadian Medical Association, 2017).

You use systems of classification to help you navigate the world. Imagine how confusing life would be if you had no categories such as male/female, young/old, tall/short, doctor/nurse/teacher. While these categories are mentally useful, they can become problematic when you use them to uphold biases and ingrained assumptions that are no longer valid. You may assume, through your biases, that elements are related when they have no relationship at all. As a result, your thinking may become limited and your grasp of reality impaired. It is often easier to spot these biases in others, but it is important for an effective communicator to become aware of them. Holding biases unconsciously will limit your thinking, grasp of reality, and ability to communicate successfully.

Key Takeaways

- Language, while a powerful tool for communication, is governed by various rules (syntactic, semantic, and contextual) that determine the order, meaning, and contextual appropriateness of words. However, even with these rules in place, the potential for miscommunication exists due to cultural and individual differences in interpreting meanings.

- The ladder of abstraction demonstrates that language can simplify or distort our understanding of concepts, moving from concrete experiences to more generalized or abstract terms. While language helps humans organize and classify their understanding of the world, it can also perpetuate biases, stereotypes, and outdated assumptions, potentially hampering effective communication.