4.1 Getting to Know Your Audience

[Author removed at request of original publisher]

Learning Objective

- Describe three ways to better understand and reach your audience.

Writing to your audience’s expectations is key to your success, but how do you get a sense of your readers? Research, time, and effort. At first glance, you may think you know your audience, but if you dig deeper, you will learn more about them and become a better speaker.

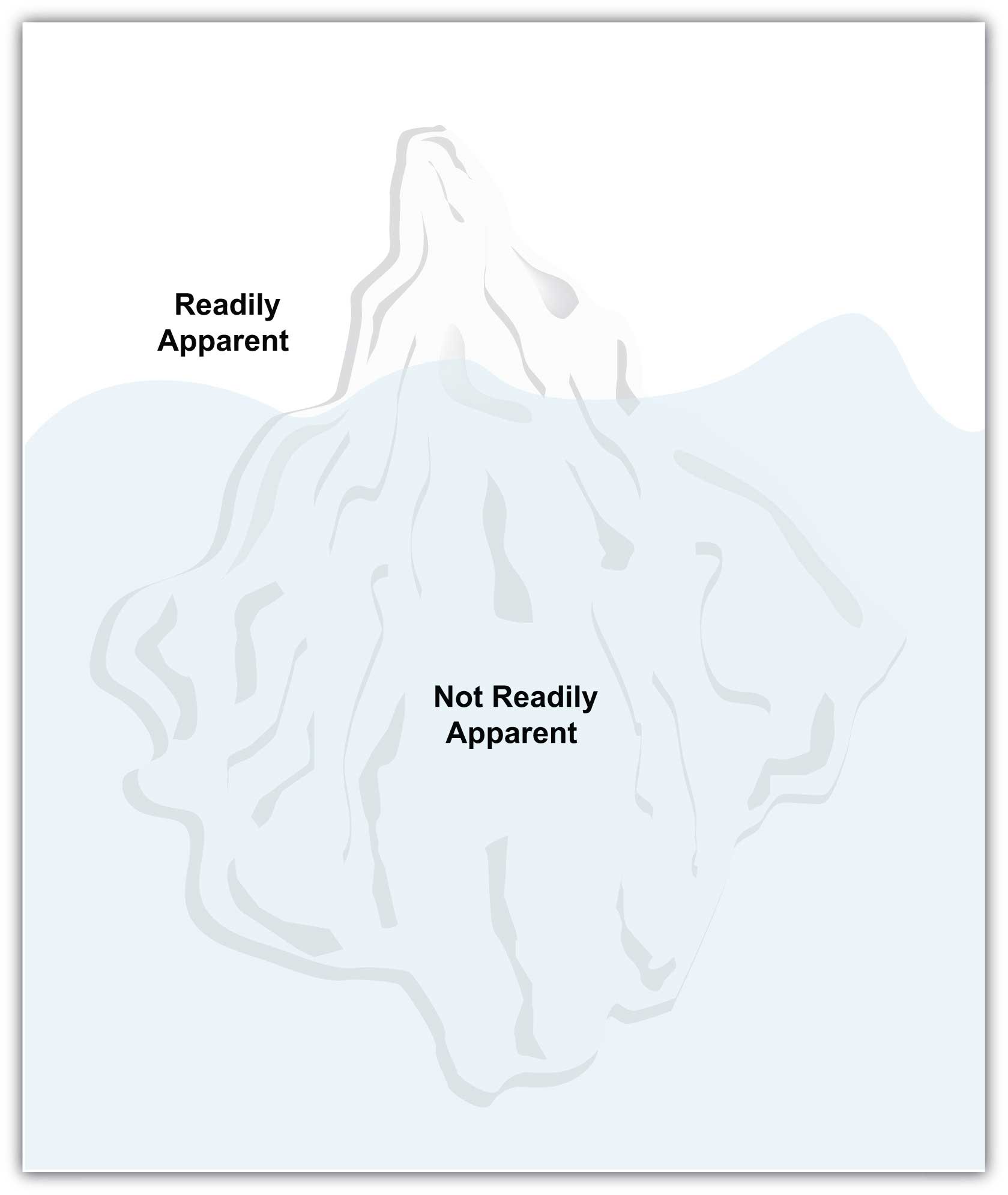

Examine Figure 4.1.1 “Iceberg Model”, often called the iceberg model. When you see an iceberg in the ocean, the majority of its size and depth lie below your level of awareness. When you write a document or give a presentation, each person in your reading or listening audience is like the tip of an iceberg. You may perceive people of different ages, races, ethnicities, and genders, but those are only surface characteristics. This is your challenge. When you communicate with a diverse audience, you are engaging in intercultural communication. The more you learn about the audience, the better you will be able to safely and effectively navigate the waters and your communication interactions.

Theodore Roosevelt pointed out that “the most important single ingredient in the formula of success is knowing how to get along with people.” Knowing your audience well before you speak is essential. Here are a few questions to help guide you in learning more about your audience:

- How big is the audience?

- What are their backgrounds, gender, age, jobs, education, and/or interests?

- Do they already know about your topic? If so, how much?

- Will other materials be presented or available? If so, what are they, what do they cover, and how do they relate to your message?

- How much time is allotted for your presentation, or how much space do you have for your written document? Will your document or presentation stand alone, or can you add visuals, audio-visual aids, or links?

Audience segments

One way to analyze your audience is to consider how they fit into larger groups or segments of society. Common segments to analyze include demographics, geographics, and psychographics.

Demographic traits refer to the characteristics that make someone an individual but that he or she has in common with others. For example, if you were born female, your view of the world may be different from that of a male and similar to that of many other females. Being female means that you share this “femaleness” trait with roughly half the world’s population.

How does this demographic trait of being female apply to communication? For example, we might find that women tend to be more aware than the typical male of what it means to get pregnant or go through menopause. If you were giving a presentation on nutrition to a female audience, you would likely include more information about nutrition during pregnancy and during menopause than you would if your audience were male.

We can explore other traits by considering your audience’s age, level of education, employment or career status, and other groups they may belong to. Imagine that you are writing a report on the health risks associated with smoking. To get your message across to an audience of twelve-year-olds, you would use different language and examples than what you would use for an audience of older adults. If you were writing for a highly educated audience—say, engineering school graduates—you would use much more scholarly language and rigorous research documentation than if you were writing for first-year college students.

Figure 4.1.2

Tailor your message to your audience.

Todd Lappin – David Byrne’s “PowerPoint as art” lecture – CC BY-NC 2.0.

Writing for readers in the insurance industry, you would likely choose examples of how insurance claims are affected by whether or not a policyholder smokes, whereas if you were writing for readers who are athletes, you would focus on how the human body reacts to tobacco. Similarly, if you were writing for a community newsletter, you would choose local examples, whereas if your venue was a Web site for parents, you might choose more universal examples.

Audiences tend to be interested in messages that relate to their interests, needs, goals, and motivations. Demographic traits can give us insight into our audience and allow for an audience-centred approach to your assignment, making you a more effective communicator (Beebe, 1997).

Improving Your Perceptions of Your Audience

The better you understand your audience, the better you tailor your communications to reach them. To understand them, a key step is to perceive clearly who they are, what they are interested in, what they need, and what motivates them. This ability to perceive is important for audience members from distinct groups, generations, and cultures. William Seiler and Melissa Beall offer six ways to improve our perceptions and communication, particularly in public speaking; they are listed in Table 3.1.3. “Perceptual Strategies for Success”.

Table 4.1.3. Perceptual Strategies for Success

| Perceptual Strategy | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Become an active perceiver | We need to actively seek out as much information as possible. Placing yourself in a new culture, group, or co-culture can often expand your understanding. |

| Recognize each person’s unique frame of reference | We all perceive the world differently. Recognize that even though you may interact with two people from the same culture, they are individuals with their own set of experiences, values, and interests. |

| Recognize that people, objects, and situations change | The world is changing, and so are we. Recognizing that people and cultures, like the communication process itself, are dynamic and ever-changing can improve intercultural communication. |

| Become aware of the role perceptions play in communication | Perception is an important aspect of the communication process. Understanding that our perceptions are not the only ones possible can limit ethnocentrism and improve intercultural communication. |

| Keep an open mind | The adage “A mind is like a parachute—it works best when open” holds true. Being open to differences can improve intercultural communication. |

| Check your perceptions | By learning to observe and acknowledge our own perceptions, we can avoid assumptions, expand our understanding, and improve our ability to communicate across cultures. |

Fairness in Communication

Finally, consider that your audience has several expectations of you. No doubt you have sat through a speech or classroom lecture where you asked yourself, “Why should I listen?” You have probably been assigned to read a document or chapter and found yourself wondering, “What does this have to do with me?” These questions are normal and natural for audiences, but people seldom actually state these questions in so many words or say them out loud.

In a report on intercultural communication, V. Lynn Tyler offers insight into these audience expectations, which can be summarized as the need to be fair to your audience. One key fairness principle is reciprocity– a relationship of mutual exchange and interdependence. Reciprocity has four main components: mutuality, nonjudgmentalism, honesty, and respect.

Mutuality means that the speaker searches for common ground and understanding with his or her audience, establishing this space and building on it throughout the speech. This involves examining viewpoints other than your own and taking steps to ensure the speech integrates an inclusive, accessible format rather than an ethnocentric one.

Being nonjudgmental involves a willingness to examine diverse ideas and viewpoints. A nonjudgmental communicator is open-minded and able to accept ideas that may strongly oppose his or her beliefs and values.

Another aspect of fairness in communication is honesty: stating the truth as you perceive it. When you communicate honestly, you provide supporting and clarifying information and give credit to the sources where you obtained the information. In addition, if significant evidence opposes your viewpoint, you acknowledge this and avoid concealing it from your audience.

Finally, fairness involves respect for the audience and individual members—recognizing that each person has basic rights and is worthy of courtesy. Consider these expectations of fairness when designing your message; you will more thoroughly engage your audience.

Key Takeaway

To better understand your audience, learn about their demographic traits, such as age, gender, and employment status, as these help determine their interests, needs, and goals. In addition, become aware of your perceptions and theirs, and practice fairness in your communications.

Exercises

- List at least three demographic traits that apply to you. How does belonging to these demographic groups influence your perceptions and priorities? Share your thoughts with your classmates.

- Think of two ways to learn more about your audience. Investigate them and share your findings with your classmates.

- Think of a new group you have joined or a new activity you have become involved in. Did the activity or group influence your perceptions? Explain the effects to your classmates.

- When you started a new job or joined a new group, you learned a new language to some extent. Please think of at least three words that outsiders would not know, share them with the class, and provide examples.

References

Beebe, S. [Steven], & Beebe, S. [Susan]. (1997). Public speaking: An audience-centered approach (3rd ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Seiler, W., & Beall, M. (2000). Communication: Making connections (4th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Tyler, V. (1978). Report of the working groups of the second SCA summer conference on intercultural communication. In N. C. Asuncio-Lande (Ed.), Ethical Perspectives and Critical Issues in Intercultural Communication (pp. 170–177). Falls Church, VA: SCA.