13.5 Working With Graphics

Melissa Ashman; Arley Cruthers; eCampusOntario; Ontario Business Faculty; and University of Minnesota

Graphics should never be for decoration. Instead, they should have a clear purpose and help the reader to understand something in the document that would be difficult to show with text alone. For that reason, you should take some extra steps to help your audience use the graphic effectively.

Pick The Right Graphic For Your Purpose

Different graphics have different functions, so you should choose one that meets your needs. For example, let’s say you have been asked to write a report recommending whether your company should voluntarily recall a product. You might insert a photo of the damaged product so that your readers can see proof that the damage is extensive. You might also include a diagram of the product to help the reader understand why the malfunction occurs. If you want your reader to understand that the product has been receiving a lot of customer complaints, you might create a bar chart that compares the number of complaints received by your product to those of similar products you sell.

When selecting a chart, graph or table, pick the one that fits the relationship you are trying to show. For example, if you wanted to show how something changed over time, you’d use a line graph. If you wanted to compare different numbers, you’d use a bar graph. If you wanted to show the percentages of a whole, you’d use a pie chart.

This collection of images will help you to see some popular types of charts and graphs. For a version that is accessible to print documents and screenreaders, the information is also repeated below.

Types of Charts

- Line Graph: Shows how something changed over time. Shows trends.

- Table: Shows a large amount of numerical data, especially when there are many variables.

- Bar Graph: Helps your audience to compare numbers, shows how items relate to one another.

- Pie chart: Shows the parts of a whole. Note: only use this when your data adds up to 100%. For example, if you did a survey and allowed participants to choose more than one option, a pie chart wouldn’t be appropriate.

- Checklist: Helps readers understand the steps in a process and keep track of what they have completed.

- Flowchart: Helps readers understand the steps in a process/procedure

- Infographic: Makes a lot of data accessible or entertaining to a general audience.

- Venn Diagram: Shows how different ideas or elements overlap.

- Organizational tree: Shows a hierarchy, such as the structure of an organization.

- Gantt Chart: Shows a project schedule, including what tasks must be completed and when.

Make Your Graphic

Once you understand your audience and the purpose of your graphic, it’s time to create it. Many people create charts in Excel, Word, Google Docs, or a free chart generator. Make sure that you label your chart clearly.

Integrate Your Graphic

You chose your graphic because it shows a relationship, but without additional help your readers might not see the same connections you see. Insert your graphic close to the text that discusses it, though you should make sure that your graphic fits on one page. For example, if you have written a paragraph explaining that the defective product has three times more customer complaints than similar products, you would put the bar graph that shows this data directly below.

The first mention of a graphic is called a lead-in statement. It’s also recommended to use a lead-out statement after the graphic. This is a statement that connects the figure to the material that follows.

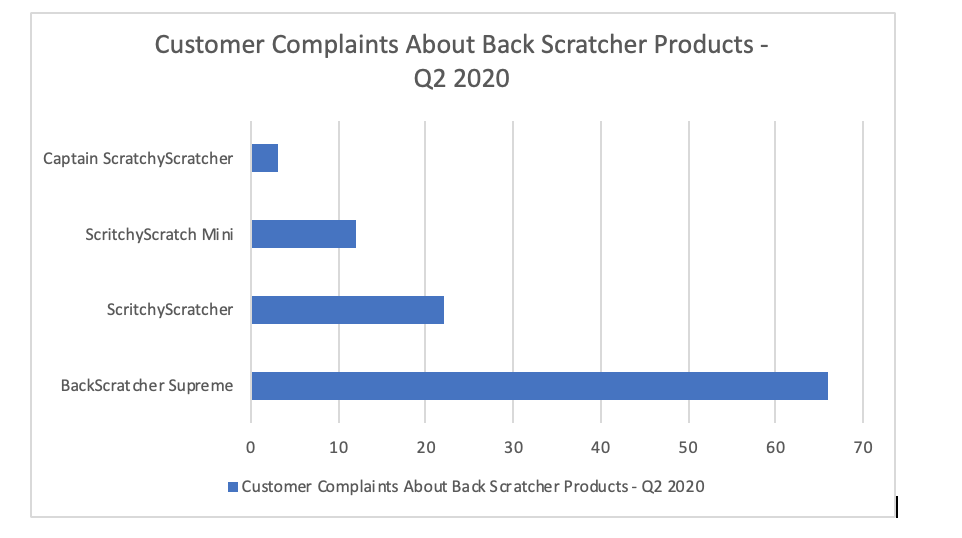

Our research shows that the BackScratcher Supreme received three times more complaints than our other backscratchers. This bar graph shows the number of customer complaints we received last quarter for each product.

Figure 13.5.1: Customer Complaints About Back Scratcher Products [Image Description]

As you can see, no other back scratcher comes close for the number of complaints. This suggests that the matter is systemic and that there haven’t been just a few isolated incidents.

Label The Graphic

Add Alt Text for the Graphic

Cite the Graphic

Just as you would cite and reference a paraphrase or a direct quote, you must also cite and reference any graphics that you use that were created by someone else or that were based on someone else’s data. Indicate the source of any graphic or data you have borrowed. Whenever you borrow a graphic or data from some other source, document that fact in the figure title using an in-text citation. You should also include the reference information in the reference list.

This reference guide from SFU tells you how to cite graphs, charts, photos and other images in a variety of settings.