Worldview Threat

Our worldview protects us from our existential fear literally and symbolically. It is probably obvious how many religions comfort us in a literal sense: They explain how we live on after death (e.g., Hades, Heaven, Sheol, reincarnation, etc.). Secular worldviews can also alleviate death anxiety (e.g., such as taking comfort in our recycling of the atoms in our body according to the Law of Conservation of Matter and Energy). It is important to note TMT does not say that any one of these worldviews is correct—either a secular view or a particular religion. Rather, TMT points out how these beliefs function to provide us with a sense of immortality. Worldviews also provide us with symbolic immortality. When we are part of a culture, we are part of something larger than ourselves, something immortal—our community, our nation. In this sense, our worldview explains where we have come from, and what will endure after us, as well as what our place is in the world. We derive a lot of our self-esteem from being part of a like-minded group, whether that be a large-scale religious community or a small scale niche community (e.g., goths, hipsters).

Because all worldviews are to some extent arbitrary, fictional assemblages about the nature of reality, they require continual validation from others in order remain believable. Exposure to cultures of people with alternate worldviews, especially those that are diametrically opposed to one’s own, therefore, potentially undermines one’s faith in the dominant worldview and the psychological protection it provides. Thus, contact with others who define reality in different ways undermines an assumed consensus for people’s death-denying ideologies, and therefore (directly and/or indirectly) calls both one’s worldview and source of self-esteem into question.

Our worldview is like a winter jacket protecting us from the icy wind of existential terror; it provides us with a shared set of beliefs about the nature of reality to help us deal with our anxiety over death. Worldviews provide us a sense of meaning and purpose, a sense of security in an unsure world. If someone challenges our worldview, they tear a hole in our jacket, letting that icy existential dread in… and we react to that threat. Thus, as individuals we can be verbally or even physically violent, and as societies we can cause tremendous harm to cultures whose existence reminds us that our worldview is constructed and thus not as immortal as we might think.

Worldview threat occurs when the beliefs one creates to explain the nature of reality (i.e., cultural worldviews) to oneself are called into question, most often by a competing belief system of some Other. Because worldview threat weakens our psychological defenses against the awareness of our mortality, we often enact compensatory behaviours against competing worldviews, and TMT researchers have identified 4 forms of worldview defense to reinstate and reaffirm the validity of our worldview and thus protect us from death anxiety:

- Derogation: The belittling of others who espouse a different worldview. If we are able to dismiss an opposing view, we thereby dismiss the validity of their worldview in relation to our own, and so in classrooms different cultural perspectives can be mocked or insulted.

- Assimilation: Involves attempts towards converting worldview-opposing others to our own system of belief. Of course, the prototypical example of assimilation is missionary work, and in education this process can take the form of teachers (or fellow students) attempting to convert students to their perspective on historical or contemporary events, as we see with the idea of teaching as an immortality project.

- Accommodation: Modifying one’s own worldview to incorporate some aspects of the threatening worldview. More specifically, through accommodation one accepts some of the peripheral components of the threatening worldview into one’s own, which renders the alternate worldview less threatening and at the same time allows one’s core beliefs to remain intact. In teaching, for example, teachers might have students make dream catchers, but fail to address the thought and beliefs behind this Indigenous practice.

- Annihilation: The most extreme example of a defense against worldview threat, annihilation involves aggressive action aimed at killing or injuring members of the threatening worldview. If groups of people with opposing beliefs can be injured or killed, the implication is that their beliefs are truly inferior to our own. Further to this point, by eliminating large numbers of people with a different version of reality, the threatening worldview may cease to exist, and thus no longer pose a threat. Some of the most horrific human behaviors throughout history, namely war and genocide, are examples of annihilation as a form of worldview defense, and in the classroom students may express support for annihilation of certain groups.

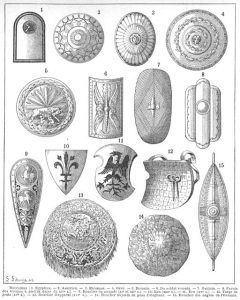

“As a teacher, I imagine everyone entering a classroom as carrying an invisible shield (worldview) with them. As with worldviews, each shield would be different, tailored to the individual holding it. As well, depending on the shield an individual holds, they may be more vulnerable to certain attacks (topics/opinions) than someone with a different shield. Early on, the type and style of shield may be heavily influenced by familial ties, maybe it has a family crest or other signifier. And like a worldview, a shield is not permanent. A different shield could be adapted as the holder evaluates the effectiveness, or lack of effectiveness, of their current shield. Some shields may be more robust than others, being able to put up with more before they yield. And perhaps most obviously, shields are typically meant for protection when they are deployed, similar to worldviews according to TMT.” (B. Bjornsson, 2019)

“As a teacher, I imagine everyone entering a classroom as carrying an invisible shield (worldview) with them. As with worldviews, each shield would be different, tailored to the individual holding it. As well, depending on the shield an individual holds, they may be more vulnerable to certain attacks (topics/opinions) than someone with a different shield. Early on, the type and style of shield may be heavily influenced by familial ties, maybe it has a family crest or other signifier. And like a worldview, a shield is not permanent. A different shield could be adapted as the holder evaluates the effectiveness, or lack of effectiveness, of their current shield. Some shields may be more robust than others, being able to put up with more before they yield. And perhaps most obviously, shields are typically meant for protection when they are deployed, similar to worldviews according to TMT.” (B. Bjornsson, 2019)Suggested Readings for further study:

Becker, E. (1973). The denial of death. Free Press.

Becker, E. (1975). Escape from evil. Free Press.

Burke, K., & van Kessel, C. (2021). Thinking educational controversies through evil and prophetic indictment: Conversation versus conversion. Educational Philosophy and Theory 53(1), 90–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2020.1767072

Hayes, J., Schimel, J., Williams, T. J., Howard, A. L., Webber, D., & Faucher, E. H. (2015). Modifying committed beliefs provides defense against worldview threat. Self and Identity, 14(5), 521–548. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2015.1036919

Jacobs, N., van Kessel, C., & Varga, B. A. (2021). Existential considerations to disrupt rigid thinking in social studies classrooms. Taboo: The Journal of Culture and Education, 20(1), 51–65. https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/taboo/vol20/iss1/4/

Schimel, J., Hayes, J., Williams, T. & Jahrig, J. (2007). Is death really the worm at the core? Converging evidence that worldview threat increases death-thought accessibility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92, 789-803. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.5.789

Solomon, S., Greenberg, J., & Pyszczynski, T. (2015). The worm at the core: On the role of death in life. Random House.

van Kessel, C. (2020). Teaching the climate crisis: Existential considerations. Journal of Curriculum Studies Research, 2(1), 129–145. https://doi.org/10.46303/jcsr.02.01.8

van Kessel, C., den Heyer, K., & Schimel, J. (2020). Terror management theory and the educational situation. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 52(3), 428–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2019.1659416

van Kessel, C., Jacobs, N., Catena, F., & Edmondson, K. (2022). Responding to worldview threats in the classroom: An exploratory study of preservice teachers. Journal of Teacher Education, 73(1), 97–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/00224871211051991

van Kessel, C., & Saleh, M. (2020). Fighting the plague: “Difficult” knowledge as sirens’ song in teacher education. Journal of Curriculum Studies Research, 2(2), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.46303/jcsr.2020.7

(Created by C. van Kessel, 2018-2021)

Is a subfield of social psychology that is derived from existentialism and the works of Ernest Becker. TMT posits that our awareness of death conflicts with our evolved desire to live and that this creates the potential for debilitating existential anxiety (i.e., “terror”). Furthermore, it proposes that humans have attempted to psychologically resolve the problem of death by inventing and sustaining self-esteem-yielding cultural worldviews that help to manage this anxiety. These cultural systems enable people to curtail death related anxiety by providing hope for immortality. According to TMT, immortality can be literal, such as a belief in an afterlife (e.g., heaven). However, we can also attain symbolic immortality through a cultural system (e.g., one’s country) which allows its adherents to construe themselves as valuable members whose memory and contributions will persist posthumously through the permanency of that culture or the objects that it fosters.

Most commonly these terms refer to the anxiety and fear that comes with knowing that we will eventually die. Existential anxiety can also refer more broadly to the unease that accompanies thinking about any potentially unpleasant aspect of our existence including meaninglessness, mortality, isolation, and freedom and responsibility.