1 Physical or Digital: The Fundamental Challenge of Modern Collection Development

Julia Sieben and Winston Pei

Introduction

With the emergence of digital book and information technologies in the last several decades, libraries are increasingly having to make decisions not only about the content that will constitute their collections, but also about the format in which they will acquire this content.

Both academic and public libraries are working more and more on developing digital collections in an effort to keep up with this changing environment. As noted by the National Information Standards Organization as far back as 2007, the development of digital collections has moved from being “an ad hoc ‘extra’ activity” to a core service in many libraries and other cultural institutions (NISO, 2007, p.1). However, it is also worth acknowledging that reader preferences remain diverse despite the adoption of newer formats. Ebooks, print books, audiobooks, and combinations of all these forms are preferred by different readers, at different times, and in different situations, and it is the job of libraries to support all of these preferences and formats (Romano, 2015). Both print and digital materials have persuasive arguments for their adoption, as well as diverse and difficult challenges surrounding their acquisition, use, and retention. These new formats make necessary a reassessment of collection use, user preferences, and collections policy and practices to enable effective collection development for both the short and long term.

This chapter seeks to give an overview of current trends and important considerations of collection development in the context of the physical vs. digital debate by investigating the benefits and limitations of both forms as well as aspects of their assessment, followed by a discussion of potential responses of libraries and scholars towards these challenges and issues, presenting both real-world examples and more general recommendations for best practices in our efforts to build balanced, effective, and sustainable collections.

Background and Current Context

The ‘technology’ for physical books has existed in some form for over 5000 years, with the earliest versions of libraries appearing soon after. That literal grounding in the physical has set the parameters for much of the traditions and practices of librarianship, with the specific development of the ‘modern’ western system of academic and public libraries taking place over the past two hundred years. But the much more recent development and widespread adoption of digital media – especially in the last two decades – has disrupted many of those practices and introduced the need for new ones designed for the digital age.

The Shift to Digital

A survey of the literature does suggest a general trend of movement towards more digital collections in libraries, both academic and public. Reviews of mid 2000’s collection management and development literature describe “the shift from print resources to electronic resources” (Xie & Matusiak, 2016, p.40) as a main characteristic of changing local collections, and this shift has continued. The academic literature is teeming with case studies of academic libraries’ processes of moving to create more digitally focused collections and pare down physical ones (Haugh, 2016; Glazier & Spratt, 2016; Demoville & Wood, 2016; Boice et al., 2017; Rao et al., 2016; Goodwin, 2014), and a study done in regards to ebook collections in public libraries across the U.S. saw 94% of respondent libraries reporting that they offered ebooks to users in 2015 (Romano, 2015), suggesting a comparable emergence of digital materials in public libraries. Although trends of digitization exist across material types, this chapter speaks more largely to the collection of monographs, with an in depth examination of digital serials and other media and materials being beyond the scope of this chapter.

Regardless of type, digital collections are growing, and further evidence of this can be seen through examining library budgets. A recent study by the Institute of Museum and Library Services found that in public libraries in the U.S. between 2014 and 2018 “per person spending on physical materials decreased by six percent, while median per person spending on electronic materials increased 31 percent” (The Institute of Museum and Library Services, 2021, p.4). Other studies show that budgets for ebooks in U.S. academic libraries increased from 7.4% to 9.3% of total budgets between 2010 and 2016, with a “similar trend [apparent in] U.S. public libraries, with increased budget share from 1.7% in 2010 to 6.3% in 2015” (Maleki, 2021a, p.993-5). In some cases, budget changes are quite drastic. For example, the Australian Curtin University Library’s ebook budget went from 52% to 90% of all monographs over a period of four years (Maleki, 2021a), and the Graduate School of Education in New York has seen ebook acquisitions take over 40-60% of the college’s book budget (Haugh, 2016).

As apparent from the above discussion, there has certainly been an increase in acquisition of electronic materials, and in some cases this very well could be at the expense of print. A 2016 study of U.S. academic libraries “showed that money spent on ebooks in about half of the libraries is likely to detriment print book budget (61%) more than any other area” (Maleki, 2021a, p.995), while a quarter of U.S. public libraries reported buying fewer print books, and 60% of U.S. public libraries reporting reallocating funding from other areas of their material budgets to purchase ebooks (Romano, 2015).

Maleki argues that “financial reasons are central to the substantial increase of ebooks and reduction in print books in academic libraries” (2021a, p.993), and cost and limited financial resources are a concern and unfortunate reality for all types of libraries. Conflicting conclusions can be seen throughout discussions of whether print or digital materials are actually more expensive, however. Some sources argue that print versions are often cheaper (Bailey et al., 2015; Rao et al., 2016), while some promote digital as the more cost effective option (Bunkell, 2009). Changing priorities in libraries, such as a shift to allocation of space to programming over shelving and storage, are also contributing to a new focus on digital over physical (Showers, 2015; Laerkes, 2016). However, cost and value should be considered with more complexity than solely dollar amounts, and consideration of immediate, long term, and peripheral costs such as storage, upkeep, and access all contribute to determining which format is most cost effective in a given library’s context.

Reader Preference, Use, and Policies

The real question is whether this reallocation towards digital is actually reflective of user preferences and therefore warranted. Rose-Wiles et al. note a 25 year trend of declining print book circulation, with their study results aligning with other reports of trends in academic libraries towards a decrease in print book circulation (2020). Other authors argue that the “decline in circulation is not universal” (Tanackovic et al., 2016, p.95) and that previous studies show mixed results on whether physical or digital books are more used (Goodwin, 2014). It is also worthwhile to note that Rose-Wiles et al.’s study continues on to suggest that “the declining use of print books is not due to increasing use of ebooks, since ebook use has declined at a similar rate” (2020, p.8), which somewhat muddles the conclusions that can be drawn on user preference. These uncertain conclusions are further complicated by developments in service delivery caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. Significant spikes in ebook and electronic resource use (Goddard, 2020) due to restrictions on physical borrowing have made digital collections an even more unignorable consideration for libraries, although whether this trend will continue past the early years of the pandemic remains to be seen.

There is also evidence that material type and subject matter correlate with format preference. For example, digital journals are being embraced more widely than scholarly monographs, which are still generally preferred in print (Showers, 2015). While print is still used for some reading and research in almost any discipline (Tanackovic et al., 2016), some areas show a higher reliance on print materials, such as social sciences and liberal arts (McCombs, G. & Moran, A., 2016), art subjects (Downey et al., 2014), as well as children’s and young adult materials (Romano, 2015).

Despite the growing prominence of digital materials, their ubiquity is not yet extensive enough to reasonably justify the abandonment of print materials. Some studies have found that significant numbers of print books lack electronic counterparts, while other studies report various levels of overlap between print and electronic duplicates, seeing ranges between about 17% to around 58% (Boice et al., 2017). These numbers also vary widely by subject matter and discipline of materials, but no subject area or discipline was found to have more than 70% of books also available in digital form (Rao et al., 2016), suggesting significant limitations in moving to entirely digital collections. Another factor Rao et al. mention that creates different considerations and opportunities across collection areas, and between public and academic library contexts, is the tendency of publishers to focus on popular titles rather than academic materials, with “academic titles [constituting] just one tenth of all e-books available in the marketplace” (Rao et al., 2016, p.448).

One last noteworthy aspect of these trends to consider is the effect they have on institutional policies. Much like for physical collections, “[d]igital library collection development policy in general consists of goals/purposes, scope/types of content, priorities, and selection criteria” (Xie & Matusiak, 2016, p.41), and traditional collection development criteria – quality, relevancy, aesthetic and usability aspects, cost, currency, value, demand, etc. – are still largely applicable to digital materials. While the foundational principles and collection development criteria are similar, they can manifest in different ways when working with digital materials. Currency concerns may be more about updating frequency (Xie & Matusiak, 2016) or issues surrounding the delay in release of ebooks versus their print counterparts, which is noted to usually be between three to eighteen months (Rao et al., 2016). Usability concerns may require new considerations like technological literacy and access to devices, and cost may need to factor in new dimensions like contract and licensing agreements and costs over time like perpetual access or archiving ability (Xie & Matusiak, 2016).

In attempts to present a clear stance on these issues, libraries have made various modifications to collections policies. For example, the University of Texas Libraries has separate collection development policies for digital materials obtained or produced in various ways, dividing purchased or licensed materials, materials digitized by the University Library or the University, and collections of links and pointers (Xie & Matusiak, 2016). Other libraries, such as the Graduate School of Education (GSE) in New York have reworked policies to specify a preference for digital materials as much as possible (Haugh, 2016).

The Debate over the “Pros” and “Cons” of Physical “Versus” Digital

A final critical piece of background and current context that needs mentioning is the ongoing debate over the supposed “pros” and “cons” of both physical and digital formats, both in librarianship and academia as well as popular media. The wide ranging views and lack of consensus speak to the ongoing adjustment to these new formats.

The key advantages to the newer digital options include ease of access, ease of storage, and the availability of additional usability features such as links to additional information and personalization of the interface. A modern e-reader device can provide access to thousands of books through an object the same size and footprint as a traditional print book, if not smaller. Advocates also tout benefits such as ease of use (i.e. in-text searching, only accessing the parts needed) and personalization (changing layouts and appearance) (Haugh, 2016), and “24/7 access when visiting the library is inconvenient or impossible, as is the case with the growing number of distance learners” (Miller & Ward, 2022, p.43). Even advocates for print acknowledge benefits to digital:

You can take thousands of digital texts on vacation without weighing down your suitcase. Electronic texts offer instant definitions or translations of words via dictionary software embedded in the reader. Digital texts often come with hyperlinks, videos, and websites embedded in the text. Plus, you don’t have to kill trees to produce a digital text, making them far more sustainable than printed books (Brand, 2016, p.44).

That said, in the time since Brand made this pronouncement, there has also been an increasing awareness of the environmental costs of digital, such as the carbon footprint of running server farms and the mining of materials needed for the manufacture of electronic products. In an article on sustainability and e-waste in InformationWeek, a U.S. west coast utility manager was quoted as saying “I can tell when a new data center comes online… The energy consumption in the system immediately spikes” (Shacklett, 2022). From energy to equipment, in his book World Wide Waste, Gerry McGovern points out how a single e-reader requires “50 times the minerals and 40 times the amount of water to manufacture than a print book” (2020), and how many print books one such device arguably ‘replaces’ is up for debate. So between the impacts from both manufacturing and ongoing usage, the sustainability advantage of digital is increasingly less clear, if it exists at all.

Meanwhile supporters of print highlight other features unique to the material physical objects, including being “human-readable,” the issue already raised earlier in this chapter that not all materials exist in digital form (Huff, 2003), a sense of reliability and authority to a print copy, the browsability in physical stacks (Rose-Wiles, 2020), and the value of a tactile experience of reading (Brand, 2016). Recent research also continues to find a preference for reading in print, despite improvements in actual reading performance using digital platforms, as well as less cognitive load with reading in print formats (Clinton, 2019; Jeong, 2021).

And in perhaps the most important indicator in the battle of print versus digital formats, a 2021 Pew Research Center survey showed that, at least in the U.S., print still dominates reader preferences, with only three in ten Americans having read an ebook in the previous year (Favario, 2022).

Challenges

In discussing the challenges raised by the topic of balancing physical and digital materials, the elephant in the library is the fact that digital materials, platforms, and tools are still so new and also still constantly changing. This introduces a level of complexity and uncertainty to which the profession will need time to adapt, and for which it will need to collect much more data with which to make better decisions. But even given this backdrop, already three key and interrelated challenges have emerged in addressing balanced collections development and management: storage, access, and preservation.

Storage

Whether addressing physical or electronic resources, storage of materials continues to present a fundamental challenge. On the physical side, there is a dual impact of not only natural limits to storage space for physical objects, but also a repurposing of existing space for uses other than stacks and storage. Showers raises the issue of the changing expectations of libraries, the result of which is that “large physical collections need to be rethought and space has to be reconfigured to meet the changing demands of users” (2015, p.24). Laerkes is even more direct, saying that simply housing collections and hosting fixed programming are “yesterday’s needs. Modern libraries are less about books and more about people and community factors” (2016, p.90). At the University of Alberta, a Canadian top five university and medical school, the design of the new replacement Health Sciences Library will include onsite storage for only 80,000 of the library’s current 200,000 titles, with the balance to be moved to the university’s Research and Collections Resource Facility (RCRF), a closed stack storage facility located on a separate campus from which less frequently used items can be requested as needed (Miller, 2020). This raises the additional wrinkle that, even as libraries transform to address questions of patron need and space utilization, the displaced physical materials still need to go somewhere, whether that means moving them to dedicated – and in some cases even more specialized – storage space elsewhere, or disposal, with or without conversion to digital forms.

Meanwhile on the digital side, while digital materials do save on traditional physical storage requirements, content being held ‘virtually’ or ‘in the cloud’ is not in reality without the need of physical infrastructure and their associated costs, such as the energy expenditures mentioned above. Furthermore, Erin Passehl-Stoddart, Head of Special Collections and Archives at the University of Idaho, rightly points out that “[d]igital storage space faces its own challenges of people thinking there is no cost to server space, or just throw everything into the cloud for cheap” (Preservation and the Future in the Northwest, 2017, p. 15). The physical infrastructure is simply more hidden now, existing as massive server farms and digital storage facilities out of the sight of patrons and librarians, a condition that actually applies equally to off site, high density physical facilities. But even if we restrict the discussion to the digital realm, digital materials still take up “space” in the form of bits and bytes of data. For libraries maintaining their own digital resources and archives, that involves maintaining extensive in-house IT infrastructure. For subscription-based digital services, that cost is once again hidden outside/behind the contractual descriptions of the services being offered. In effect, the move to digital does not ‘solve’ storage challenges, merely adds options and complexity to a fundamental problem that must still be addressed.

So while the basic question of prioritization and weeding remains the same, the increased options in format add a new layer of complexity to questions of storage. And in either case, the question of where it is stored leads directly to the question of how we then access it. Whether in a physical or digital format, library materials will serve no one if they cannot be found and used.

Access

On the physical side, the redeployment of space away from stacks directly accessible by patrons (and also librarians) means that the browsability of the physical collection becomes reduced, or at least changed. Carr provides an excellent summary of this debate in his 2015 article “Serendipity in the Stacks”, saying serendipity is “in the eyes of many, an imperiled phenomenon,” (p.832) although he concludes by saying that “librarians today will benefit from an understanding of the problematic processes and perceptions that may underlie this form of discovery” (p.840). In framing access in this way, Carr highlights not only that physical stacks may not be the only way to deliver serendipity, but that serendipity itself may in fact be a symptom rather than a solution. In particular, Carr identifies two issues with serendipity: “serendipity is problematic because it is an indicator of a potential misalignment between user intention and process outcome. And, from a perception-based standpoint, serendipity is problematic because it can encourage user-constructed meanings for libraries that are rooted in opposition to change rather than in users’ immediate and evolving information needs” (2015, p.840). That said, in their later study of the use of print books, Rose-Wiles et al. argue that even with the spread of digital information, still “many authors stress the value of browsing physical collections, especially the serendipitous discovery of material” (Rose-Wiles, 2020, p.3). But regardless of whether serendipity is a symptom or a feature, the options introduced by digital materials, as well as digital cataloguing and searching, do cast the qualities of physical materials in a new light, with other basic characteristics of physical materials now potentially reframed as limitations. For example, the fact that access to physical materials requires physical presence and potentially travel, either by the patron or the object, creates a friction that has always been a limitation to access, but now heightened by the relative ease in the distribution of digital resources.

And yet access to digital resources is not without its own limitations. On one level, the fact that digital materials are not directly human-readable creates an immediate digital divide, where access to the materials also requires access to an extensive additional infrastructure that includes computers or computing devices, electrical power generation, and the internet. This is compounded by a skills divide, where not only is basic literacy required for access to these materials, but an accompanying level of digital literacy is necessary now as well.

The required, and ironically very physical, ‘digital’ infrastructure is also a contributing factor in the reallocation of physical space in libraries, where the square footage formerly used for storage of physical materials is often being replaced, at least in part, with the computer workstations needed to access materials or for patrons to bring in and use their own equipment to do the same. To return to the example of the new University of Alberta Health Sciences Library, Chief Librarian Dale Askey describes how “[s]tudy spaces, group study rooms, more technology, and possible quasi-lab spaces are all part of the vision for the modernized Health Sciences Library space” (Miller, 2020).

Just as access to physical resources was limited by the control of the materials, for example the chaining of physical books to lecterns or the literal gatekeeping at the doors of monasteries and private libraries, digital materials bring with them similar challenges, again made more complex by the new options and dynamics they introduce. For example, the new digital subscription models, with their unique storage issues mentioned previously, also introduce the digital equivalents of chains and gatekeepers in the form of Digital Rights Management (DRM) and membership-only access, whether granted to individuals or institutions. The way these new digital gates and chains operate also represents a more fundamental shift in power in terms of control over information resources. The concern around such limitations is such that in 2019 the Canadian Federation of Library Associations released their “Position Statement on E-Books and Licensed Digital Content in Public Libraries,” raising the issue that:

Many publishers withhold ebooks from public libraries, or use excessive pricing and restrictive licensing to make purchasing functionally impossible for some libraries. This situation will deteriorate if the Canadian government does not take action by identifying policy solutions that prevent restrictive licensing and pricing practices and encourage fair commercial practice (CFLA, 2019, p.1).

They conclude by arguing that the Government of Canada needs to develop policy solutions that ensure access to digital content through libraries, thus also highlighting the new legal complexities that digital materials have introduced to librarianship. While the underlying principles of copyright are certainly not new, their application in relation to new digital technologies and distribution models very much is. In discussing digital-native concepts like perpetual access, Polchow rightly identifies that “[i]n the process of exploring perpetual access, knowledge of licensing and the legal framework is important, as well as understanding copyright and fair use… perpetual access to e-resources encompasses a complex ecosystem of licensing agreements and copyright law, technological infrastructure, and staff expertise” (2021, p.111). And this is only one of many implementations of digital access.

Digital resources introduce a challenging new landscape for librarians to navigate, and place new responsibilities onto librarians’ shoulders to be aware of the legal ramifications of the collection, access, and use of their materials.

Then even as questions of storage and access are being addressed, the question that immediately follows is “for how long?” And once again, both physical and digital realms share challenges, this time with preservation.

Preservation

This preservation question is two-fold: 1) For how long should we keep the materials in question? And, especially relevant to digital materials, 2) for how long can we keep the materials in question?

For physical materials, the question of preservation is on one level closely tied to that of storage. Since the first clay tablets, of which some remain but certainly not all, physical materials have been at risk from the “Ten Agents of Deterioration”: dissociation, theft, physical forces, fire, water, incorrect temperature, incorrect humidity, exposure to light, pests, and pollutants (Canadian Conservation Institute, 2017). Especially if the goal is preservation, storage facilities need to be designed to address all ten of these factors, which contributes to the cost of storage, not to mention ongoing maintenance and care by professionals. But with proper care, physical materials have proven to be long lasting, with known parameters for preservation. That said, the costs and investment required are also well known.

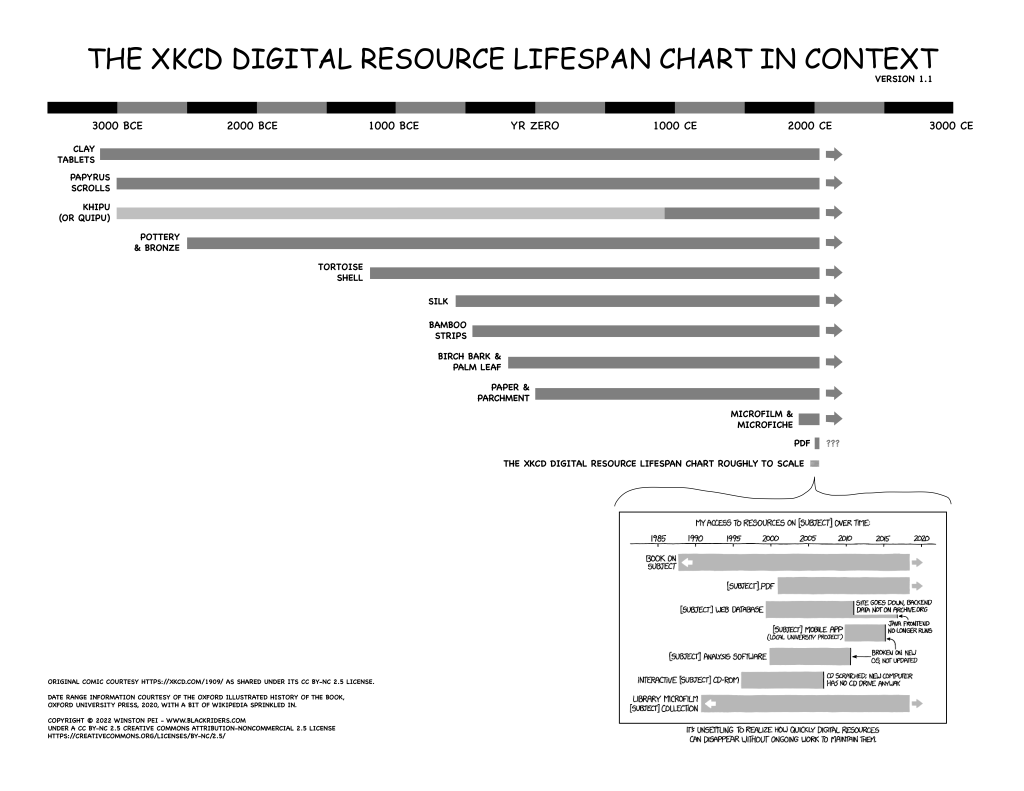

In contrast, the question of digital preservation again takes on an added level of complexity impacted not only by traditional deterioration issues, but also by issues of technology and business models. One basic challenge is the notably short lifespans of digital media and technologies, especially in contrast to traditional physical ones, as highlighted in Figure 1 below.

As mentioned previously, digital infrastructure still lives on physical infrastructure and that infrastructure remains vulnerable to flood and fire, physical forces, theft/vandalism, temperature, and the like, albeit in different ways. But then other uniquely digital challenges also come into play. Already there are materials that are no longer usable because of the obsolescence of the mediating technology layer, such as materials stored on Zip disks, in an expired file format, or the expiry of the original hosting website. In their introduction to Government Information in Canada, Wakaruk and Li (2019) outline numerous examples of this kind of issue within the Government of Canada, from a collection of research reports and transcripts submitted to the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples being available only through a now obsolete software application and operating system, to whole websites and web content removed without official documentation, for policy reasons that fail to take into account the importance of preservation. And returning to their article outlining perpetual access to digital materials, Polchow makes clear the complexity of digital preservation of e-resources, including “navigating intellectual property, social contracts, and technology access issues, and finding methods to handle an increase in the number of Open Access resources” (2021, p.107). They continue by outlining issues with link rot, content retrieval issues with open access materials, and the continuing expansion of e-resource formats. In their Digital Preservation Handbook, the Digital Preservation Coalition also outlines several other threats to digital materials, including the phenomenon known as ‘bit rot’ where “streams of bits need to be captured and retained over time, without loss or damage, to ensure the survival of digital materials… bits [that] may be ignored, abandoned, accidentally deleted or maliciously destroyed” (2022).

This added complexity and contrast in lifespan and history is perhaps the biggest differentiator when comparing physical with digital resources.

In short, the major issues of collection management, such as storage, access, and preservation, have not been “solved” by the development of digital alternatives. Both physical and digital materials provide unique benefits that serve differing needs for patrons and librarians alike, but the challenges remain, and if anything have been made more complex by the introduction of new technological options. And unlike the underlying code of our digital options, the answer is not binary.

Ultimately, it is simply that most basic of librarianship questions – what do we keep?

Responses

In responding to these challenges, a handful of approaches stand out as important considerations for future collection development and management: collective collections, “rightsizing” and conscious selection, and appropriate tools for access and assessment.

Collective Collections

The idea of collective collections speaks to a more holistic approach to collection management. In effect it is an extension of the ‘E’ in the MUSTIE methodology for collection maintenance and weeding, where materials might be removed based on being (M)isleading, (U)gly, (S)uperseded, (T)rivial, (I)rrelevant, or available (E)lsewhere (American Library Association, 2018). As Miller and Ward rightly warn, if libraries all weed their collections individually and with little or no coordination, what will remain will be an uncoordinated, piecemeal collection of what is left (2022). The idea of the collective collection then is to work together in order to make more efficient use of space and resources, and applies to both physical and digital collections.

In regards to physical materials, collective collections or “shared print programs” are initiatives largely borne in the academic library sphere that see libraries “collaborating to retain, develop, and provide access to their physical collections” (Miller & Ward, 2022, p.42). Various sources also cite examples and promote collaboration at institutional or organizational, regional, or national levels that involves coordinating preservation and storage efforts, and by extension de-duplication and withdrawal activities (Showers, 2015; Schmidt, 2016).

These approaches can save money and space, both physical and digital, for many libraries. Linares & Ferrer explain that currently many libraries already share storage facilities, albeit with little collaborative management between collections (2016). They go on to say that “cooperative storage is seen as the most practical and effective solution to the efficient supply of low-use print materials which also solves the problems of limited space in libraries” (Linares & Ferrer, 2016, p.171). By coordinating their storage activities, all parties could benefit. While all of Schmidt’s mentioned examples of collective collection efforts did report savings on capital expenditures by not having to build new local storage facilities and in reduced maintenance costs enabled by economies of scale (2016), it is important to remember that these benefits come with their share of potential challenges. Shared vision, agreements on service models and ownership of materials, coordination of different databases and library systems, development of shared principles and practices, especially in approaches to metadata, and determination of appropriate collection arrangements can all become potential obstacles in efforts to build and maintain collective collections (Schmidt, 2016).

Collaborative collection management in the digital context is often implemented in closer relation to the selection process, as opposed to a greater focus on retention, deselection, and withdrawal in regards to print materials. In order to address current challenges such as financial constraints and widely varying user needs and preferences, it is suggested that “a collaborative digital collection should be the direction of libraries” (Xie & Matusiak, 2016, p.41). Collective collection development can reduce costs and lead to increased access. Partnership between institutions can bring access to resources that would be otherwise unaffordable individually, and institutional coalitions can lead to increased bargaining power during vendor negotiations, enabling libraries to advocate for more favourable terms of use for the digital resources in question (Xie & Matusiak, 2016). These aspects of terms and licensing can also create potential challenges in a cooperative context, however, for example fair allocation of access between consortial group member institutions of different sizes in situations where licensing is based upon a certain number of uses. Beyond complex issues of licensing and terms of use, as with shared print collections, collaborative digital collections also come with their own list of other caveats. They can lead to reduction of local autonomy and collection diversity, create issues when it comes to trying to keep institutional user data separate, and limit member libraries’ ability to build collections to satisfy their unique needs (Xie & Matusiak, 2016).

A closely related branch of collective digital collections is the concept of ebook interlibrary loans (ILL), a phenomenon closely researched by Zhu in 2018. Zhu describes two main views on ebook ILL among library scholars: 1) the pessimistic perspective that licensing issues have “deadlocked [ebook] usage through ILL” (Zhu, 2018, p.344) and that it would require an unrealistic amount of work to try and change these existing practices and structures, and 2) a more optimistic perspective that sees space for ILL librarians to work to reduce restrictions and obstacles through local license negotiations to facilitate increased resource sharing and ebook ILL. Zhu’s study found that although the majority of libraries rejected ILL requests for complete ebooks, they were slightly more likely to fill chapter requests. Zhu also notes that it is not uncommon for libraries to simply have policies that they do not practice ebook ILL as a matter of convenience in order to avoid messy licensing and legal concerns. This comes at the potential cost of “opportunities to maintain and advocate for a sharing culture and tradition” (Zhu, 2018, p.349). Zhu draws from their findings that “[t]he future of [ebook] ILL may depend on the evolution of larger issues, such as open access, scholarly communication methods, adoption of new purchasing/access models, and the continuing negotiation between libraries and the publishers/vendors regarding the use rights of electronic resources” (Zhu, 2018, p.350), and appears to align more closely with the optimistic viewpoint, promoting library advocacy towards greater opportunities for sharing digital resources.

“Rightsizing” and Conscious Selection

As discussed throughout this chapter, there are many reasons why libraries may not want to focus solely on either physical or digital collections, and from the evidence presented, in general a best practice would appear to be finding a balance between print and electronic materials. One example of an approach to this issue is the practice of “rightsizing,” which is an “ongoing process that maintains a collection’s optimal physical size” (Miller & Ward, 2022, p.42). While “rightsizing” is the specific and named approach largely developed by Ward, the literature does lend further support to the underlying concepts, with others such as Rose-Wiles et al. similarly promoting balanced collections and “working from the premise that print books still have value in an academic library, [suggesting] that a better solution will be to improve the content, design and promotion of print collections in ways that complement rather than compete with electronic resources and physical workspaces” (2020, p.10). As mentioned earlier, some subject areas are characterized by low preference for and availability of electronic resources, making a complete shift to digital collections unrealistic. Disciplines like the social sciences and liberal arts have shown greater preference for print materials (McCombs & Moran, 2016), while in subject areas like visual arts it is unclear whether low penetration of electronic resources is due to preference or low availability of digital materials (Yao, 2014). In any case, authors such as Boice et al. echo sentiments like that of Rose-Wiles et al., agreeing that both effective management of physical collections as well as incorporation of alternative formats are important (Boice et al., 2017).

While these approaches often do favour electronic over print materials where possible, they do so with an eye to sustainability, stressing both the importance of stability in electronic access, and the retention and preservation of important and unique print resources, drawing on practices of collective collections and shared print programs to optimize the efficiency of these activities (Ward & Miller, 2022).

Emerging practices such as controlled digital lending can also be potential solutions to concerns about preserving physical materials safely in the context of the legal complexities surrounding digitization. Conscious attention in selection efforts can also play a big role in optimizing balance and efficacy of collections. Joint suggests that issues that arise in digital collection preservation can in some cases be mitigated by choosing appropriate collections to acquire in the digital form. For example, resources such as exam guides or practice tests that are quickly outdated and not retained for long periods of time would not necessitate the same attention to worrying about being lost or inaccessible years down the road in the case of system or software updates (Joint, 2006). Beyond content of the collections, different selection models and practices can also assist in maximizing balance and usefulness of collections. Methods like data- or patron-driven acquisitions and selective title purchasing over mass electronic package deals can often lead to higher use, closer alignment with user needs and preferences, and lower costs (Haugh, 2016), although these approaches come with their own pitfalls of potentially limiting diversity and the long-term research value of academic collections (Blume, 2019).

Accurate assessment of usage and need

As with almost every other dimension of collection management, the fundamental issues facing both physical and digital collection assessment and evaluation are again similar between formats. In both cases it is essential to reflect on whether our assessment and evaluation tools are giving an accurate picture of the ways and amounts that resources are being used in order to determine if collections are effectively serving users and worth the money and resources libraries expend to acquire and maintain them. White raises an important point in their claim that “the term ‘use’ as utilised by library scientists, is often vague, general, and can mean any interaction involving a library” (White, 2021, p.110). While the basic goal – an accurate depiction of use – is the same, once again the considerations and approaches taken to print and digital materials need to be slightly different.

Increasingly important as justification for retention of print materials and browsable in-house stack space, especially in the face of increasingly digital collections and increasingly diverse physical library spaces, a large focus of print collection assessment is on assessing use beyond just circulation statistics or check-outs, which can be deceptively misrepresentational of actual use of materials. Rose-Wiles et al. describe methods to attempt to measure in-house use, including counts for re-shelving and methods like monitoring papers that would be disturbed when an item was taken off the shelf or moved. They also note that surveys assessing user re-shelving of materials suggest that even these methods most likely significantly underestimate actual in house usage levels (Rose-Wiles et al., 2020). But even accounting for the level of estimation, these methods can give libraries a more quantitative argument for retaining print materials in the physical library.

Similarly, the most obvious measurements for digital materials, such as ebook circulations and views, can also give incomplete insight into the usage and value of electronic resources. Citations, downloads, and altmetrics are suggested as supplementary assessment dimensions to give a more holistic picture. Citations are seen as a more telling measure of impact for scholarly work, while downloads can suggest use for less scholarly or academic purposes. Alternative metrics, or altmetrics, is a “type of crowd-sourced peer-review or practice” and can help identify use in less conventional spheres and applications (White, 2021, p.110). Turnaway rates, or the number of times users try to view a single use ebook that is already currently being used, are yet another metric that can be helpful for libraries in making selection decisions and for justifying certain access terms or models for electronic resources (Haugh, 2016).

In a slightly different but related way, holdings data has also traditionally been used to measure impact of materials, and can factor into collection development decisions. Maleki has done considerable work in holdings and impact assessment, and suggests that print holdings “indicate a more stable distribution pattern” (Maleki, 2021a, p.1017), while differences in acquisition methods (most notably package purchasing/licensing of e-resources) can lead to deceptive appearances in digital and ebook holdings (Maleki, 2021b). Thus it is recommended to use total holdings data more carefully, and further speaks to the importance of having a close and critical eye to the methodology and analysis involved in evaluation of collections.

Multiple methods of access

Yet another aspect factoring into the use and efficacy of collections is usability and ways in which resources can be accessed. Print materials obviously benefit from being kept in prominent physical locations where they can be easily seen and browsed, however presentation must be considered in regards to digital collections, too. Some illustrations of this are Perrin’s examples of a yearbook digitization project at Texas Tech University, and digitization of materials in the Lubbock City Planning Project. The yearbook project was an incredibly time and effort intensive project that spent two years producing metadata for digitized objects in order to deliver features that in the end were not particularly valued or important to the user base, while the Lubbock City Planning Project is a cautionary tale of incomplete planning and lack of communication in a multi-phased digitization of the City Planning Department’s documents, with differences in document types and related metadata capabilities between phases resulting in a rather dysfunctional overall collection. Unfortunately, often the presentation of digital collections is based more on “what the project team thinks would be good than what patrons actually need” (Perrin, 2016, p.241) and leads to a lot of wasted time and effort. Libraries are encouraged to learn from these mistakes and put conscious effort into the display and accessibility of collections.

In regards to access and use of collections, there have also been some innovative and interesting approaches that attempt to reduce the differences between physical and digital materials. Enis (2014) describes instances of physical libraries endeavouring to match the convenient anytime- and anywhere-accessible nature inherent in digital resources with their physical collections. Although they have reportedly had varying levels of success and have come with their own challenges, ideas like library vending machines – automated units with small collections that can facilitate checkouts, returns, membership registrations, and holds pickups – and smartlockers that make hold pickups available across a wider range of times and locations (Enis, 2014) are a few examples of libraries bringing physical collections further outside their doors and making them more conveniently accessible in ways that could potentially put them on closer footing with digital resources.

In the other direction, there have also been efforts to make using electronic materials more similar to the experience of reading a physical book. Many of the more anecdotal pieces arguing for retention of print books mention the feeling of holding a book, turning the pages, the smell of an old volume, or on a slightly more ‘scientific’ level, the value of using physical elements to aid in memory or information retrieval (Brand, 2016). Display platforms have addressed these preferences by allowing readers options to use page turning graphics and sounds, by retaining original pagination or layouts in digital formats (Brand, 2016), or in one case by offering scratch and sniff stickers that can be placed on the hardware used to access digital materials to emulate the musty smell of old books (Sweeney, 2009).

Approaches such as these attest to the value of being in tune with user needs and preferences. Through close attention and awareness of what users actually want, and with a little bit of effort and innovation, libraries can make significant strides to offset both the objective and the more subjective disadvantages of both print and digital collections. At the end of the day, it is unlikely that everyone will be 100% satisfied all the time no matter what libraries do, but there are certainly many realistic solutions to many of the challenges of delivering balanced and useful overall collections to users.

Conclusion

The balancing of collections between physical and digital materials arguably underpins and complicates all other aspects of collection management in contemporary librarianship. And yet the solutions remain as fundamental as the challenges. The major themes in response – collective collections, “rightsizing” and conscious selection, accurate assessment of usage and need, multiple methods of access – would apply even if digital materials were not at issue and the profession of librarianship had only to adjust to the growth in volume in print materials. Although there may be unprecedented complexity and pace of change associated with digital materials, the process and rationale for that change will simply be a continuation of the work librarians have been doing since the inception of the profession.

That said, we can conclude one thing: our ultimate response will be physical AND digital, not one or the other, just as librarians have adapted our methods and approaches to the change from clay to papyrus and fabric, to paper and parchment, to microfiche and tape, taking full advantage of the unique qualities of each new medium. Provided we continue to keep our ultimate purpose and goals in mind even as we focus and specialize on particular aspects of librarianship, the issues of media and format will continue to resolve themselves in their time.

Sources for Further Reading

Brand, C. (2016). In defense of the printed book. RBM: A Journal of Rare Books, Manuscripts, & Cultural Heritage, 17(1), 44–46. https://doi.org/10.5860/rbm.17.1.457

Recommended as a reminder that there is more to the experience of reading than simply information-seeking, such as Brand’s description of “the pinch,” that moment when a reader knows they are near the end of the book because there are so few pages left between the fingers of one hand, “the physical manifestation of the emotion a reader experiences near the end of a good book” (p. 45).

Darnton, R. (2010). The case for books: Past, present, and future. Public Affairs. https://archive.org/details/caseforbookspast0000darn

Written by former Director of the Harvard University Library and a pioneer in the history of the book, The Case for Books is a collection of essays, lectures, and other writings by Robert Darnton discussing the place of physical books in the digital world. Of particular interest would be the chapter titled “The Future of Libraries” in which Darnton concludes with a call to “[d]igitize and democratize” (p. 58).

Goodwin, C. (2014). The e-Duke scholarly collection: E-book v. print use. Collection Building, 33(4), 101-105–105. https://doi.org/10.1108/CB-05-2014-0024

An interesting case study of the Kimbel Library at Coastal Carolina University comparing print and e-book use between identical titles with the goal of determining format preference. While there are some limitations and it is a fairly specific case study, it is relatively rare for studies to compare format preferences between entirely identical titles.

NISO Framework Working Group. (2007). A framework of guidance for building good digital collections. https://www.niso.org/sites/default/files/2017-08/framework3.pdf

A guide of best practices from the National Information Standards Organization with support from the Institute of Museum and Library Services in regards to digital collection development of cultural institutions. It aims to provide an overview of components and processes, identify and collect further resources, and encourage community participation and conversation surrounding the management and development of digital collections.

Romano, R. (2015). Sixth annual survey of ebook usage in U.S. public libraries. Library Journal. https://s3.amazonaws.com/WebVault/ebooks/LJSLJ_EbookUsage_PublicLibraries_2015.pdf

A relatively recent resource presenting the findings of an extensive survey on ebook usage in U.S. public libraries. Interesting quantitative and more generalizable data on ebook usage in the public library context.

Smith, P. (2021, April 16). The viability of E‐Books and the survivability of print. Publishing Research Quarterly (2021) 37. (pp. 264–277). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12109-021-09800-1

A useful analysis of the “complex relationship between publishing and the digital sphere” comparing ebooks and traditional publishing. Explores issues including the differing business models between Apple and Amazon for ebooks, digital rights management, privacy and consumer data, and the enduring appeal of print books.

Ward, S. M. (2015). Rightsizing the academic library collection. ALA Editions, an imprint of the American Library Association.

Gives a detailed guide to ‘rightsizing’ or optimizing of physical collections to best serve users, with a focus on academic libraries specifically. The book aims to help librarians approach evaluation and deselection, and to offer practical advice.

References

American Library Association. (2018). Collection maintenance and weeding. http://www.ala.org/tools/challengesupport/selectionpolicytoolkit/weeding

Bailey, T., Scott, A., & Best, R. (2015). Cost differentials between e-books and print in academic libraries. College & Research Libraries, 76(1), 6–18. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.76.1.6

Blume, R. (2019). Balance in demand driven acquisitions: The importance of mindfulness and moderation when utilizing just in time collection development. Collection Management, 44(2-4), 105-116. https://doi.org/10.1080/01462679.2019.1593908

Boice, J., Draper, D., Lunde, D., & Schwalm, A. (2017). Preservation for circulating monographs: Assessing and adapting practices for a changing information environment. Technical Services Quarterly, 34(4), 369-387. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317131.2017.1360640

Brand, C. (2016). In defense of the printed book. RBM: A Journal of Rare Books, Manuscripts, & Cultural Heritage, 17(1), 44–46. https://doi.org/10.5860/rbm.17.1.457

Bunkell J. (2009). E-books vs. print: Which is the better value?…Taking the sting out of serials! NASIG 2008. Proceedings of the North American Serials Interest Group, Inc. 23rd Annual Conference, June 5-8, 2008, Phoenix, Arizona. Serials Librarian, 56(1–4), 215–219.

Canadian Conservation Institute. (2017, September 26.) Agents of deterioration. https://www.canada.ca/en/conservation-institute/services/agents-deterioration.html

Carr, P. L. (2015). Serendipity in the Stacks: Libraries, Information Architecture, and the Problems of Accidental Discovery. College & Research Libraries, 76(6), 831–842. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.76.6.831

Canadian Federation of Library Associations [CFLA]. (2019, Jan). Position statement on e-books and licensed digital content in public libraries. http://cfla-fcab.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/CFLA-FCAB_position_statement_ebooks.pdf

Clinton, V. (2019). Reading from paper compared to screens: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Research in Reading, 42(2), 288–325. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9817.12269

Darnton, R. (2010). The case for books: Past, present, and future. Public Affairs. https://archive.org/details/caseforbookspast0000darn

Demoville, N. & Wood, A. (2016). Get ‘em in, get ‘em out: Finding a road from turnaway data to repurposed space. Serials Librarian, 70(1–4), 266-271. https://doi.org/10.1080/0361526X.2016.1159424

Digital Preservation Coalition. (2022). Preservation issues. Digital Preservation Handbook [website]. https://www.dpconline.org/handbook/digital-preservation/preservation-issues

Downey, K., Zhang, Y., Urbano, C. & Klinger, T. (2014). A comparative study of print book and DDA ebook acquisition and use. Technical Services Quarterly, 31(2), 139-160. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317131.2014.875379

Enis, M. (2014). Remotely convenient: From vending machines to lockers, innovative solutions take the physical library collection outside the building, where it can be accessed 24-7, just like the digital one. Library Journal, 139(10), 46.

Favario, M. & Perrin, A. (2022, January 6). Three-in-ten Americans now read e-books. Pew Research Center [website]. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2022/01/06/three-in-ten-americans-now-read-e-books/

Glazier, R., & Spratt, S. (2016). Space case: Moving from a physical to a virtual journal collection. Serials Librarian, 70(1–4), 325–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/0361526X.2016.1157011

Goodwin, C. (2014). The e-Duke scholarly collection: E-book v. print use. Collection Building, 33(4), 101-105. https://doi.org/10.1108/CB-05-2014-0024

Haugh, D. (2016). How do you like your books: Print or digital? An analysis on print and e-book usage at the Graduate School of Education. Journal of Electronic Resources Librarianship, 28(4), 254-268. https://doi.org/10.1080/1941126X.2016.1243868

The Institute of Museum and Library Services. (2021). The use and cost of public library materials: Trends before the COVID-19 pandemic. Institute of Museum and Library Services.

Jeong, Y. J. & Gweon, G. (2021, October 21). Advantages of Print Reading over Screen Reading: A Comparison of Visual Patterns, Reading Performance, and Reading Attitudes across Paper, Computers, and Tablets. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 37(17), 1674-1684. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2021.1908668

Joint, N. (2006). Digital library futures: Collection development or collection preservation? Library Review, 55(5), 285-290. https://doi.org/10.1108/00242530610667549

Laerkes, J. (2016). Building public libraries for tomorrow. In J. Hafner & D. Koen. (Eds.) Space and collections earning their keep : Transformation, technologies, retooling. (pp.81-91) De Gruyter Saur.

Linares, S. & Ferrer, L. (2016). From room for books to room for users: An old infantry barracks meets the challenge. In J. Hafner & D. Koen. (Eds.) Space and collections earning their keep : Transformation, technologies, retooling. (pp.170-179) De Gruyter Saur.

Maleki, A. (2021a). OCLC library holdings: Assessing availability of academic books in libraries in print and electronic compared to citations and altmetrics. Scientometrics 127, 991–1020.

Maleki, A. (2021b). Why does library holding format really matter for book impact assessment?: Modelling the relationship between citations and altmetrics with print and electronic holdings. Scientometrics 127, 1129–1160.

McCombs, G. & Moran, A. (2016). The die is not yet cast: The value of keeping an open mind and being agile throughout all phases of the renovation planning cycle. In J. Hafner & D. Koen. (Eds.) Space and collections earning their keep : Transformation, technologies, retooling. (pp.120-136) De Gruyter Saur.

McGovern, G. (2020, April). World wide waste. Gerry McGovern [website]. https://gerrymcgovern.com/ books/world-wide-waste/introduction-why-digital-is-killing-our-planet/

Miller, M. & Ward, S. (2022). Rightsizing your collection. American Libraries Magazine. https://americanlibrariesmagazine.org/2022/05/02/rightsizing-your-collection/

Miller, P. (2020, Dec 3). Gift to health sciences library kickstarts library modernization project. The Gateway. https://thegatewayonline.ca/2020/12/gift-to-john-w-scott-health-sciences-library-kickstarts-library-modernization-project/

NISO Framework Working Group. (2007). A framework of guidance for building good digital collections. https://www.niso.org/sites/default/files/2017-08/framework3.pdf

Pei, W. (2022, March 17). The XKCD digital resource lifespan chart in context [diagram]. https://www.blackriders.com/mental-mulch/XKCD-digital-lifespan-chart-in-context

Perrin, J. (2016). Lessons learned: A case study in digital collection missteps and recovery. In B. Eden (Ed.), Envisioning our preferred future: New services, jobs, and directions. (pp.93-120). Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Polchow, M. (2021). Exploring Perpetual Access. Serials Librarian, 80(1–4), 107–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/0361526X.2021.1883206

Rao, K., Tripathi, M., & Kumar, S. (2016). Cost of print and digital books: A comparative study. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 42(4), 445–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2016.04.003

Romano, R. (2015). Sixth annual survey of ebook usage in U.S. public libraries. Library Journal. https://s3.amazonaws.com/WebVault/ebooks/LJSLJ_EbookUsage_PublicLibraries_2015.pdf

Rose-Wiles, L., Shea, G., & Kehnemuyi, K. (2020). Read in or check out: A four-year analysis of circulation and in-house use of print books. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 46(4). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2020.102157

Schmidt, J. (2016). Panel discussion on collaborative storage: A global perspective. In J. Hafner & D. Koen. (Eds.) Space and collections earning their keep : Transformation, technologies, retooling. (pp.195-205). De Gruyter Saur.

Shacklett, M. E. (2022, November 29). IT’s role in sustainability and e-waste. InformationWeek. https://www.informationweek.com/sustainability/it-s-role-in-sustainability-and-e-waste

Showers, B. (Ed.). (2015). Library analytics and metrics : Using data to drive decisions and services. Facet Publishing.

Smith, P. (2021, April 16). The viability of e‐books and the survivability of print. Publishing Research Quarterly (2021) 37. (pp. 264–277). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12109-021-09800-1

Sweeney, S. (2009). In defense of books: library director Robert Darnton says the form will survive. The Harvard Gazette. https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2009/12/in-defense-of-books/

Tanackovic, S., Badurina, B., & Balog, K. (2016). Physical library spaces and services: The uses and perceptions of humanities and social sciences undergraduate students. In B. Eden (Ed.), Envisioning our preferred future: New services, jobs, and directions. (pp.93-120). Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Wakaruk, A., & Li, S. (2019). The Evolution of Government Information Services and Stewardship In Canada. Government Information in Canada. (pp.XII-XXXI). University of Alberta Press. https://doi.org/10.7939/r3-21ja-gd03

Ward, S. M. (2015). Rightsizing the academic library collection. ALA Editions, an imprint of the American Library Association.

White, H. (2021). Moving beyond downloads and views when assessing digital repositories. In G. Haddow & H. White (Eds.). Assessment as information practice: Evaluating collections and services. (pp. 107-117). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003083993

Xie, I. & Matusiak, K. (2016). Discover digital libraries: Theory and practice. Elsevier.

Yao, J. O. (2014). Art e-books for academic libraries: A snapshot. Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America, 33(1), 27–40. https://doi.org/10.1086/675704

Zhu, X. (2018). E-book ILL in academic libraries: A three-year trend report. Journal of Academic Librarianship, 44(3), 343–351.

Appendix A: Long Description of Figure 1 – The XKCD Digital Resource Lifespan Chart in Context

This figure consists of a horizontal bar-style chart showing a comparative timeline of different book technologies.

Under the title of The XKCD Digital Resource Lifespan Chart in Context, version 1.1, there is an alternating bar of black and grey rectangles representing a 6000-year scale of time in 500-year increments, labelled every 1000 years from 3000 BCE to 3000 CE.

Below the timescale are twelve bars representing different book technologies, with the bars 1 to 4 spanning most of the width of the figure, bars 5 to 9 spanning approximately half the width, and bars 10 to 12, which represent technologies that require additional equipment in order to read the book, spanning less than 1/100th of the width:

- Clay Tablets – a dark grey bar from approximately 3200 BCE to 2000 CE, with an arrow indicating a continuation into the future

- Papyrus Scrolls – a dark grey bar from approximately 3000 BCE to 2000 CE, with an arrow indicating a continuation into the future

- Khibu (or Quipu) – a light grey from approximately 3000 BCE to 900 CE, then a dark grey bar from 900 CE to 2000 CE, with an arrow indicating a continuation into the future

- Pottery & Bronze – a dark grey bar from approximately 2500 BCE to 2000 CE, with an arrow indicating a continuation into the future

- Tortoise Shell – a dark grey bar from approximately 1200 BCE to 2000 CE, with an arrow indicating a continuation into the future

- Silk – a dark grey bar from approximately 600 BCE to 2000 CE, with an arrow indicating a continuation into the future

- Bamboo Strips – a dark grey bar from approximately 400 BCE to 2000 CE, with an arrow indicating a continuation into the future

- Birch Bark & Palm Leaf – a dark grey bar from approximately 200 BCE to 2000 CE, with an arrow indicating a continuation into the future

- Paper & Parchment – a dark grey bar from approximately Year 0 to 2000 CE, with an arrow indicating a continuation into the future

- Microfilm & Microfiche – a short dark grey bar from approximately 1800 CE to 2000 CE, with an arrow indicating a continuation into the future

- PDF – a tiny narrow grey bar spanning approximately 20 years, from 2000 to 2020, with three question marks after indicating an uncertain future

- The XKCD Digital Resource Lifespan Chart Roughly to Scale – a tiny light grey rectangle spanning approximately 40 years, from 1980 to 2020

In the bottom right hand quadrant of the chart, the original XKCD comic, titled My Access to Resources on [Subject] Over Time, is reproduced as a zoomed in detail of the grey rectangle in row 12 above. It shows a time scale in five-year increments from 1985 to 2020, with seven bars below it:

- Book on Subject – full width grey bar with arrows on both ends indicating extension beyond the timescale

- [Subject].pdf – a grey bar running from 2003 to the left edge, with an arrow on the right indicating extension beyond the timescale

- [Subject] Web Database – a grey bar running from approximately 1999, with part of the bar ending at 2011 with the label “Site goes down, backend data not on Archive.org” and the rest ending at 2017 with the label “Java frontend no longer runs”

- [Subject] Mobile App (Local University Project) – a grey bar running from 2010 to 2015, ending with the label “Broken on new OS, not updated” pointing to it with an arrow

- [Subject] Analysis Software – a grey bar running from 2000 to 2010, ending with an arrow pointing to it from the same label as above, “Broken on new OS, not updated”

- Interactive [Subject] CD-ROM – a grey bar running from approximately 1995 to 2007, ending with the label “CD scratched, new computer has no CD drive anyway.”

- Library Microfilm [Subject] Collection – full width grey bar with arrows on both ends indicating extension beyond the timescale

Below the image is a caption that reads “It’s unsettling to realize how quickly digital resources can disappear without ongoing work to maintain them.”

In the bottom left quadrant of the figure, the small print reads “Original comic courtesy https://xkcd.com/1909/ as shared under its CC BY-NC 2.5 license. Date range information courtesy of the Oxford Illustrated History of the Book, Oxford University Press, 2020, with a bit of wikipedia sprinkled in. Copyright © 2022 Winston Pei – www.blackriders.com – under a CC BY-NC 2.5 Attribution-NonCommercial 2.5 license https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.5/