5 Chapter 3 – Jean-Léon Gérôme

Faith Marion

Audio recording of the full chapter can be found here: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1t83be0KUpNTuBNUQwYZzS3tq3r-SRZbF/view?usp=sharing

Jean-Léon Gérôme was a French painter and sculptor who produced countless enticing creations which have impacted many artists and has left an influence on the art world as we know it today. Gérôme was born in Vesoul France in May 1824.[1] He was the son of a goldsmith jeweler, and by the time he was 17 he had been accepted into school in Paris.[2] While in Paris, Gérôme studied under Paul Delaroche.[3] Briefly, Gérôme made a living as a Greek and Latin tutor before his artistic vision officially took off.[4] He was also very skilled at knowing just how much paint he was going to need for mixing and painting. American painter Cady Eaton, had the opportunity to observe Gérôme while he painted and later said he, “knew the exact amount of every pigment necessary for the production of any required color, tone, shadow. When the work was finished, his palette was clean.”[5]

Just like his palette, Gérôme believed in keeping a clean workspace, he would never leave any paint to dry on the floor.[6] Out in public he also preferred to keep a clean-cut appearance, and never look out of sorts. Gérôme became quite popular amongst collectors, and through his creations, and the practices he utilized, he earned a lifetime of awards and has left an impact on the world. This paper will dissect Gérôme’s career, art techniques, and social beliefs, to address his influence on movements of contemporary art and explore the inspiration his work has had on the art of pop culture.

In the early years when Gérôme started showing his work at the Salon, a select group of artists grew a large fascination for him. This school of artists was known as the Neo-Greeks and they decided to have Gérôme be their new leader.[7] During the height of his career, he was considered to be an academic artist and he held a leading position in the Salon for over two decades, his art was beautiful and precise but critics said it lacked emotion, they felt his work was an end, not a beginning.[8] Gérôme had an unpopular fascination with the blaireau, also known as the badger-brush. The blaireau was a tool made from the long thick hair of a badger which resembled a powder puff.[9] The purpose of this tool was to give the piece a nice finish; the artist starts with a clean brush and circles it along the painting to smooth it out.[10] When art critic Edmond wrote about this technique in Gérôme’s work, they called it “polie et blaireautee” or “polished and licked.”[11] The majority of the critics during this time did not appreciate the badger-brush in the same way that Gérôme had.[12] Although this brush was common for painters to possess, many if not most landscape artists would refuse to use it, claiming the tool took too much time and patience.[13] It was largely agreed upon that the only use for the badger-brush was assisting in the creation of cloudless skies or a calm pond.[14]

Throughout Gérôme’s life he had collected many medals from exhibiting his work. In 1855 he was chevalier de la Legion d’Honneur, and he was also a professor of painting at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, a position he held for over forty years.[15] As a professor, he cared very deeply about his teaching practices and in doing so, made many life-long bonds with his students who all highly respected and appreciated him.[16] In 1863 Gérôme married a woman named Marie Goupil whose father was very influential in the art community.[17] Marie’s father, Adolph Goupil was a worldwide dealer and publisher in reproducing art; he had the latest technology and many connections with the best critics.[18] Gérôme would get his paintings photographed, copied and printed regularly by Goupil which assisted in increasing Gérôme’s popularity.[19] In 1864 the Ecole des Beaux-Arts upgraded the curriculum being taught and in the following year Gérôme was elected to be a painter in the Académie des Beaux-Arts.[20] Later in 1876 he became a member of the council Superieur des Beaux-arts, along with many more titles and achievements.[21] In 1893 he made his first appearance in the Art Institute Museum, with a total of five pieces making up the collection – three paintings and two sculptures.[22]

His first painting displayed was Portrait of a Woman (1851), the woman being Rosine Faivre who was the wife of Gérôme’s life-long friend Etienne Marie Faivre.[23] Another of the paintings displayed in the museum was The Chariot Race (1876).[24] The Chariot Race is a great piece that shows the large interest that Jean-Léon Gérôme had with the classical past. This oil painting depicts ancient Rome which was a common theme amongst many of his pieces. Gérôme’s high interest for this theme has even influenced early Hollywood, as seen in the award-winning Gladiator.[25] Another painting that is noticeably similar to The Chariot Race, is Circus Maximus. The lucky collector who purchased Circus Maximus paid $29,000 for it.[26] Love Conquers All (1889) was the third addition to the collection.[27] After this piece was created, Gérôme showed it at the Salon, and critics were not in favour of it. The painting was displayed under the name, “Whoever You Be, Here is Your Master. He is, He Was, or He Should Be” a quotation that was thought to be from Voltaire, and considered to be an inscription on a cupid statue somewhere in his home.[28]

Another theme seen throughout Gérôme work is Anacreon which is presented in one of the sculptures shown at the museum, Anacreon with the Infants Bacchus and Cupid (1881).[29] Anacreon was a lyric poet who was born in Teos, a Greek City in c. 570 BC, but his poetry can only be found in scattered fragments.[30] The last piece to be included in the collection is Napoleon Entering Cario (1897).[31] This sculpture was one of Gerome’s most successful pieces. It was part of the equestrian series and shows the young Napoleon entering the Egyptian capital in 1798 after his victory in the Battle of the Pyramids.[32]

Gérôme did not start sculpting until after his painting career had already developed, and when he did, he found himself losing the high prestige he once had and was now competing with the young artists at the start of their careers.[33] Gérôme was considered a beginner within the sculpting community, however, he did not let that stop him from accumulating a multitude of awards and achievements for his sculptures.

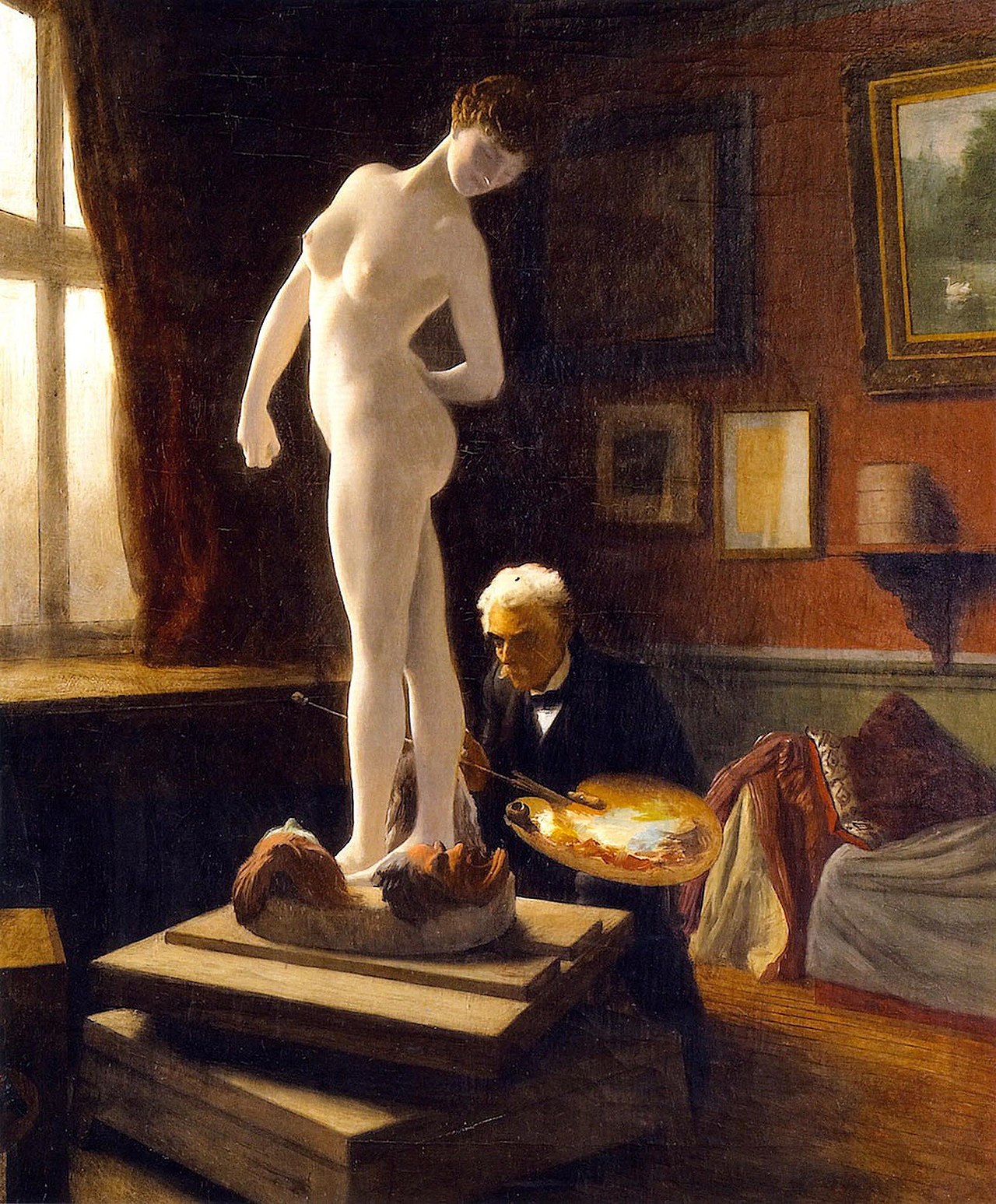

His first sculpture to be shown was The Gladiators in 1878 and the exhibition catalogue for the Universal Exposition listed him twice – as a painter and as a sculptor.[34] There were many honours and awards listed under painter, while for the sculpture’s description listed only that he was a student of Delaroche.[35] During this period where Gérôme was shifting into sculpting, he also painted many self-portraits depicting himself at work in his studio space. It is possible that the decision Gérôme made in creating these portraits was due to the noticeable change made in his status when he began exhibiting sculptures.[36]

Depicting himself hard at work while sculpting would show the critics his talent and personal investment regarding the new medium. In Gérôme’s self-portraits, he would show himself wearing his smock and apron, while using clay or plaster to sculpt a nude female figure.[37] Interestingly enough, he reserved his sculpting studio for these portraits, never showing himself in his painting studio.[38] The model would pose in an inviting way allowing the viewer to take in both her and the sculpture.[39] Gérôme understood the power a female nude had with the ‘male gaze’ and by painting himself neutral while in the presence of a naked woman, he hoped to bring more attention to his masculinity.

Gérôme did not believe that men and women should be working together in the same building; he felt that women were of best use as the model. Due to these beliefs, he found it very difficult when female artists were finally accepted to work at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. Although he did not stop the movement from happening, he managed to delay the acceptance for several years. Gérôme was part of the committee at the Ecole that was in charge of making the decision.[40] In 1889 the Union de Femmes Peintres et Sculpteurs at the Congres International des Oeuvres et Institutions Feminines at the Universal Exposition offered the proposal of allowing female artists into the Ecole.[41] The following year, the committee and the leaders of the Union gathered for a meeting regarding the issue. Most members of the committee were against the idea of working alongside women – they were worried it would be too ‘distracting’. Gérôme, who was also in favour of terminating the idea, brought up an issue regarding the budget, which ultimately resulted in a denied acceptance for women; female artists were not able to work freely in the Ecole until 1897.[42]

Just like in the way he presented himself and his studio to the public, Gérôme had a vision for his and everyone else’s art. Gérôme had hoped for a universal technique to producing art, he wanted young artists to follow his lead. He believed in “mathematical accuracy” within all creations, and had a strong opinion about the new artists who had different styles than he.[43] He even had strong feelings against Donatello and Michelangelo – he felt their work was inadequate, which was a very unpopular opinion compared to the public.[44] Although during his later years when Gerome struggled to adapt to the change happening with the preferred art style within the community, he was always persistent in creating what he believed was the best.

Bibliography

Arbós, Joan Mut. “Gallop to Feedom: On the Importance of the Classical Sources for Gérôme’s Circus Maximus.” Arion: A Journal of The Humanities and The Classics Trustees of Boston University Through It’s Publication 30, no.3 (2023): 5-73 https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/428/article/888629

Brown, Jack Perry. “The Return of The Salon: Jean- Léon Gérôme in The Art Institute.” The Art Institute of Chicago 15, no.2 (1989): 154-173 180-181 https://www.jstor.org/stable/4113019?origin=crossref&seq=16&x=124.01380583466289&y=42.460844730418934&w=884.0138058346625&h=574.4476770674559&index=13

Glessner, R. W. “The Passing of Jean- Léon Gérôme.” Brush and Pencil 14, no.1 (1904): 54-76. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25540492

Jones, Jonathan. “Jean-Léon Gérôme: Orientalist Fantasy Among the Impressionists.” The Guardian (2012) https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/jonathanjonesblog/2012/jul/03/jean-leon-gerome-orientalism-impressionists

Kruger, Matthias. “Jean- Léon Gérôme, His Badger and His Studio.” Hiding Making-Showing Creation the Studio from Turner to Tacita Dean (2013): 43-61. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt6wp7vb.7

Vors, Frédéric. “Jean- Léon Gérôme.” The Art Amateur 1, no. 4 (1879): 70-71. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25626860

Waller, Susan. “Fin de partie: A Group of Self Portraits by Jean-Léon Gérôme.” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 9, no. 1 (2010): https://www.19thcartworldwide.org/spring10/group-of-self-portraits-by-gerome

- Frederic Vors, “Jean-Léon Gérôme,” The Art Amateur 1, no.4 (1879): p.70, https://www.jstor.org/stable/25626860 ↵

- Jack Perry Brown, “The Return of the Salon; Jean- Léon Gérôme in the Art Institute,” The Art Institute of Chicago 15, no.2 (1989): p. 156, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4113019 ↵

- Frederic Vors, “Jean- Léon Gérôme,” The Art Amateur 1, no.4 (1879): p.70, https://www.jstor.org/stable/25626860 ↵

- Joan Mut Arbos, “Gallop to freedom: On the Importance of the Classical Sources for Gérôme’s Circus Maximus,” Arion: A Journal of the Humanities and the Classics 30, no.3 (2023) pp.55-73, https://doi.org/10.1353/arn.2023.0000 ↵

- Matthias Kruger, “Jean- Léon Gérôme, His Badger and His Studio,” Hiding Making - Showing Creation: The Studio from Turner to Tacita Dean no.2 (2013): p.48, https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt6wp7vb.7 ↵

- R. W. Glessner, “The Passing of Jean- Léon Gérôme,” Brush and Pencil 14, no.1 (1904): p.60, https://www.jstor.org/stable/25540492 ↵

- R. W. Glessner, “The Passing of Jean-Léon Gérôme,” p.66 ↵

- Jack Perry Brown, “The Return of the Salon; Jean-Léon Gérôme in the Art Institute,” The Art Institute of Chicago 15, no.2 (1989): p. 173, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4113019 ↵

- Matthias Kruger, “Jean- Léon Gérôme, His Badger and His Studio,” Hiding Making - Showing Creation: The Studio from Turner to Tacita Dean no.2 (2013): p.43, https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt6wp7vb.7 ↵

- Matthias Kruger, “Jean-Léon Gérôme, His Badger and His Studio,” p.43 ↵

- Matthias Kruger, “Jean-Léon Gérôme, His Badger and His Studio,” p.43 ↵

- Matthias Kruger, “Jean-Léon Gérôme, His Badger and His Studio,” p.44 ↵

- Matthias Kruger, “Jean-Léon Gérôme, His Badger and His Studio,” p.51 ↵

- Matthias Kruger, “Jean-Léon Gérôme, His Badger and His Studio,” p.52 ↵

- Jack Perry Brown, “The Return of the Salon; Jean Leon Gerome in the Art Institute,” The Art Institute of Chicago 15, no.2 (1989): p. 155, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4113019 ↵

- Jack Perry Brown, “The Return of the Salon,” p. 157 ↵

- Jack Perry Brown, “The Return of the Salon,” p. 156 ↵

- Susan Waller, “Fin de partie: A Group of Self-Portraits by Jean- Léon Gérôme,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 9, no.1 (2010): par.50, https://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/spring10/group-of-self-portraits-by-gerome ↵

- Susan Waller, “Fin de partie: A Group of Self-Portraits by Jean- Léon Gérôme,” par.50 ↵

- Jack Perry Brown, “The Return of the Salon; Jean- Léon Gérôme in the Art Institute,” The Art Institute of Chicago 15, no.2 (1989): p. 157, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4113019 ↵

- Jack Perry Brown, “The Return of the Salon,” p.156 ↵

- Jack Perry Brown, “The Return of the Salon,” p.155 ↵

- Jack Perry Brown, “The Return of the Salon,” p.156 157 ↵

- Jack Perry Brown, “The Return of the Salon,” p.156 ↵

- Jonathan Jones, “Jean- Léon Gérôme: Orientalist Fantasy Amongst the Impressionists,” The Guardian (2012): par.3, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/jonathanjonesblog/2012/jul/03/jean-leon-gerome-orientalism-impressionists ↵

- Joan Mut Arbos, “Gallop to freedom: On the Importance of the Classical Sources for Gérôme’s Circus Maximus,” Arion: A Journal of the Humanities and the Classics 30, no.3 (2023) pp.55-73, https://doi.org/10.1353/arn.2023.0000 ↵

- Jack Perry Brown, “The Return of the Salon; Jean- Léon Gérôme in the Art Institute,” The Art Institute of Chicago 15, no.2 (1989): p. 156, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4113019 ↵

- Jack Perry Brown, “The Return of the Salon,” p.165-167 ↵

- Jack Perry Brown, “The Return of the Salon,” p.156 ↵

- Jack Perry Brown, “The Return of the Salon,” p.170 ↵

- Jack Perry Brown, “The Return of the Salon,” p.155-156 ↵

- Jack Perry Brown, “The Return of the Salon,” p.172 ↵

- Susan Waller, “Fin de partie: A Group of Self-Portraits by Jean- Léon Gérôme,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 9, no.1 (2010): par.15, https://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/spring10/group-of-self-portraits-by-gerome ↵

- Susan Waller, “Fin de partie: A Group of Self-Portraits by Jean- Léon Gérôme,” par.14 ↵

- Susan Waller, “Fin de partie: A Group of Self-Portraits by Jean- Léon Gérôme,” par.14 ↵

- Susan Waller, “Fin de partie: A Group of Self-Portraits by Jean- Léon Gérôme,” par.2 ↵

- Susan Waller, “Fin de partie: A Group of Self-Portraits by Jean- Léon Gérôme,” par.1 ↵

- Susan Waller, “Fin de partie: A Group of Self-Portraits by Jean- Léon Gérôme,” par.2 ↵

- Susan Waller, “Fin de partie: A Group of Self-Portraits by Jean- Léon Gérôme,” par.2 ↵

- Susan Waller, “Fin de partie: A Group of Self-Portraits by Jean- Léon Gérôme,” par.18 ↵

- Susan Waller, “Fin de partie: A Group of Self-Portraits by Jean- Léon Gérôme,” par.18 ↵

- Susan Waller, “Fin de partie: A Group of Self-Portraits by Jean- Léon Gérôme,” par.44 ↵

- R. W. Glessner, “The Passing of Jean- Léon Gérôme,” Brush and Pencil 14, no.1 (1904): p.62, https://www.jstor.org/stable/25540492 ↵

- R. W. Glessner, “The Passing of Jean- Léon Gérôme,” p. 62 ↵