12 Chapter 9 – Japonisme

Asian Art Museum, “Looking east: how Japan inspired Monet, Van Gogh and other Western artists,” in Smarthistory, January 31, 2016, https://smarthistory.org/looking-east-how-japan-inspired-monet-van-gogh-and-other-western-artists/.

Audio recording of chapter opening segment:

Audio recording of the full chapter can be found here: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1RBlMfumneDT82Q975sWL8SFa8bG-IwL5/view?usp=sharing

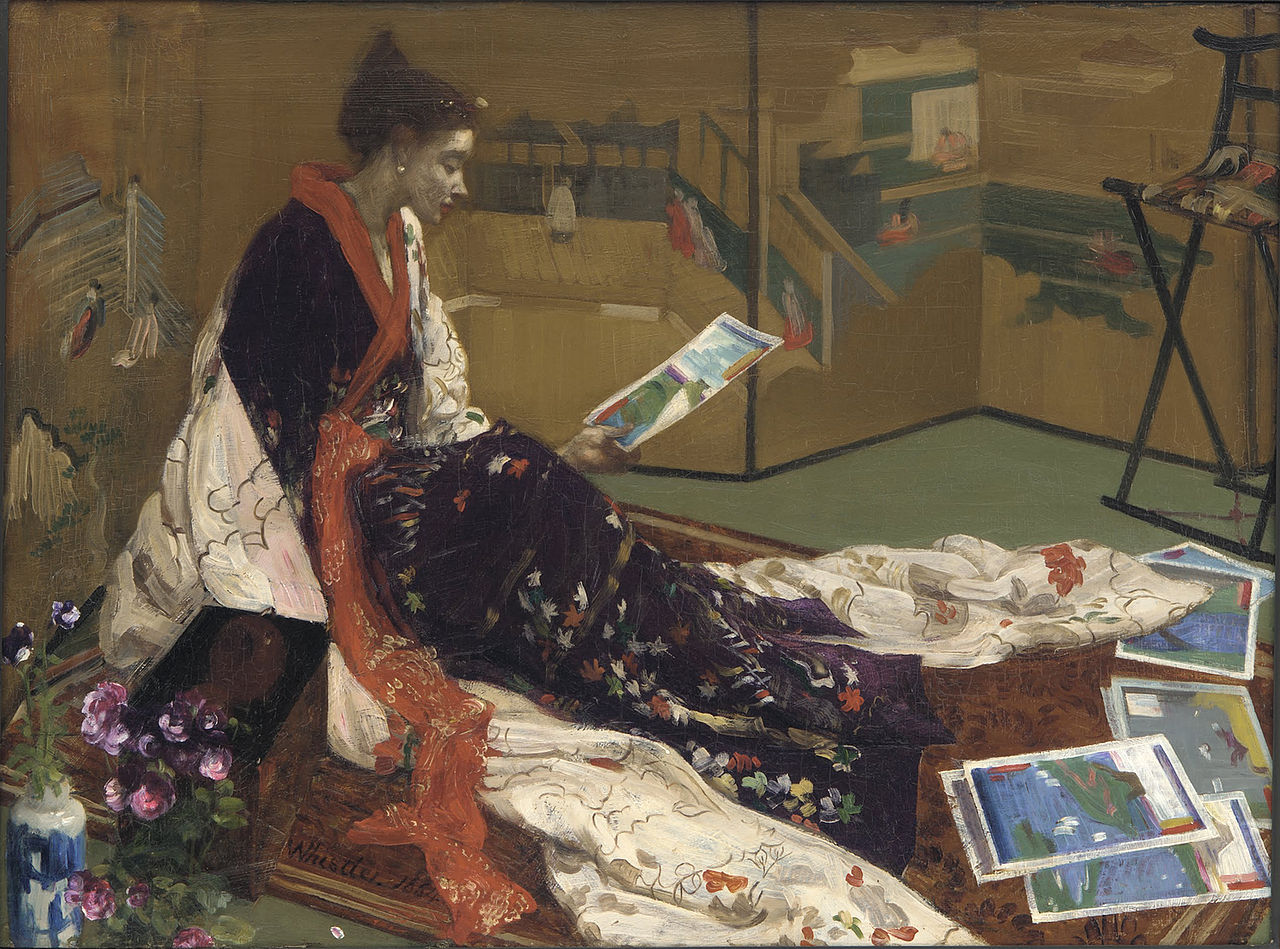

James McNeill Whistler’s Caprice in Purple and Gold is an early example of Japonisme, a term coined by the French art critic Philippe Burty in 1872. It refers to the fashion for Japanese art in the West and the Japanese influence on Western art and design following the opening of formerly isolated Japan to world trade in 1853. In Whistler’s painting, a European woman sits on the floor wearing richly embroidered silks like those of a Japanese courtesan while she studies a set of woodblock prints by the Japanese artist Hiroshige. Decorative objects from both Japan and China surround her, including a large gold Japanese folding screen.

The late-nineteenth century Western fascination with Japanese art directly followed earlier European fashions for Chinese and Middle Eastern decorative arts, known respectively as Chinoiserie and Turquerie. The art dealer Siegfried Bing was one of the earliest importers of Japanese decorative arts in Paris. He sold them in his shop La Porte Chinoise, as well as promoting them in his lavish magazine Le Japon Artistique, published from 1888-1891. Bing was also a major supporter of Art Nouveau, a fin-de-siècle (end of century) decorative style greatly influenced by Japonisme.

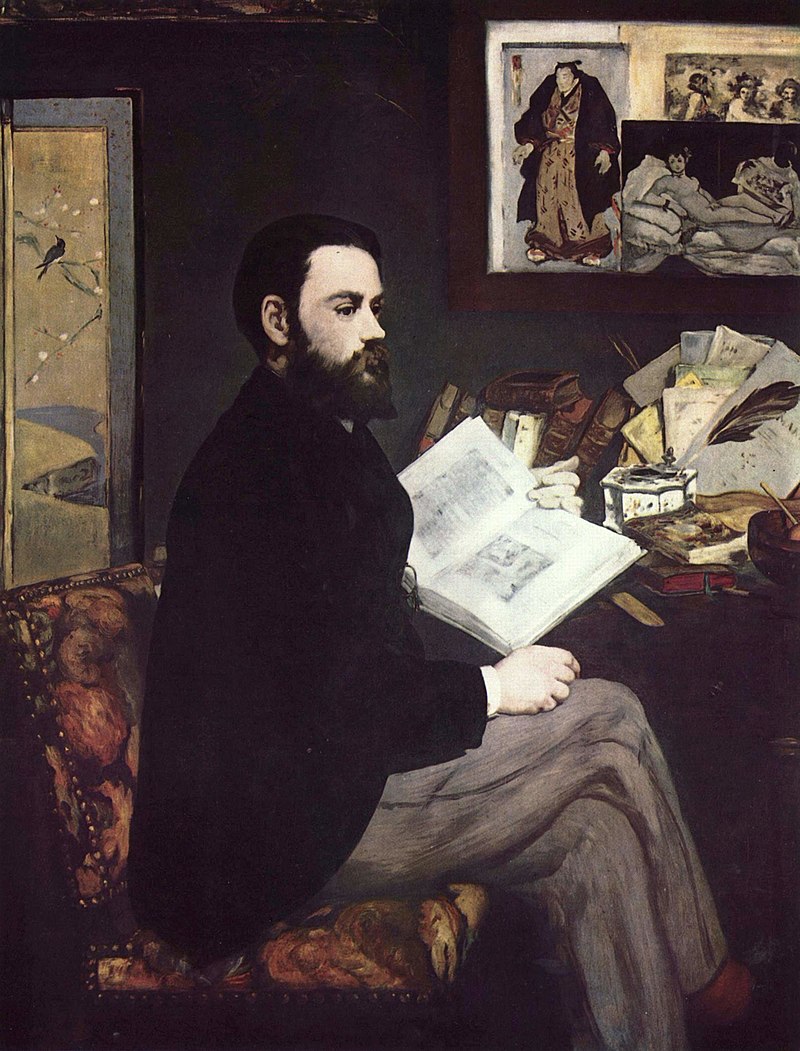

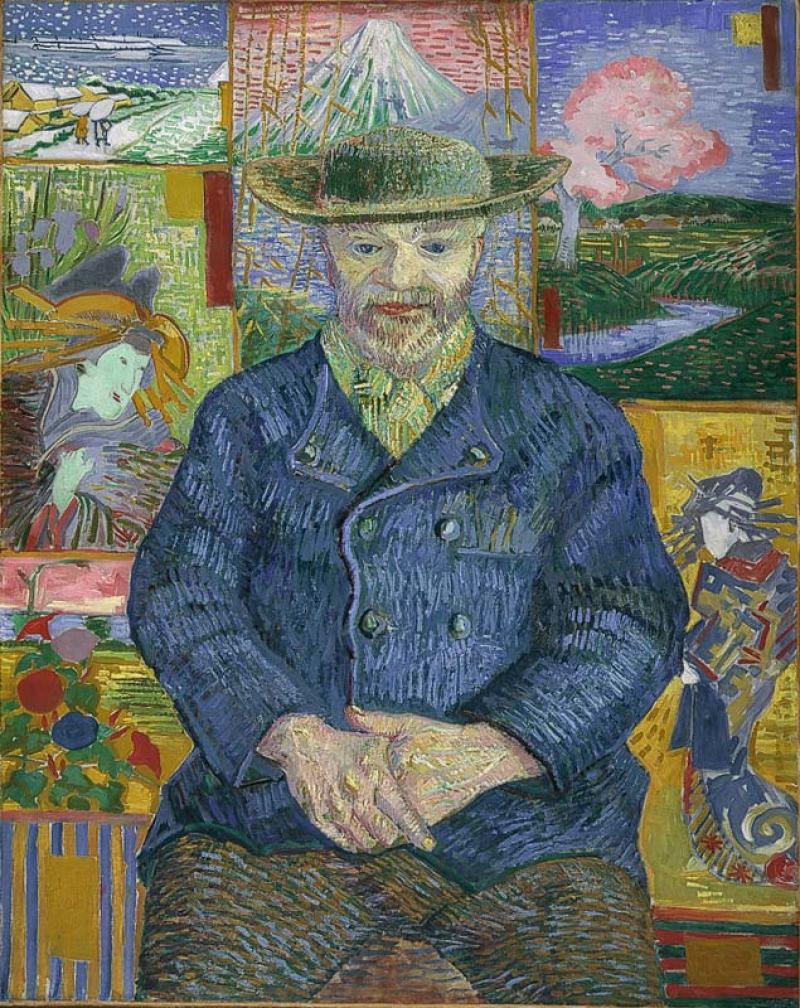

Works by prominent artists associated with Impressionism and Post-Impressionism bear witness to the late 19th-century fashion for Japanese art and decorative objects. In Manet’s portrait of Emile Zola the novelist and art critic sits at his overflowing desk. Immediately noticeable among the artworks surrounding him are a Japanese woodblock print of a wrestler and a Japanese gold screen. Monet portrayed his wife Camille dressed in a Japanese kimono surrounded by Japanese fans, and his water garden at Giverny was inspired by Japanese gardens depicted in prints and included a Japanese-style wooden bridge. In addition to painting copies of several Japanese woodblock prints, such as Bridge in the Rain (After Hiroshige), Vincent van Gogh depicted them in the background of several portraits.

![By Claude Monet - the-athenaeum.org [1], Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5749305](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/99/Water-Lilies-and-Japanese-Bridge-%281897-1899%29-Monet.jpg/1024px-Water-Lilies-and-Japanese-Bridge-%281897-1899%29-Monet.jpg)

Japonisme coincided with modern art’s radical upending of the Western artistic tradition and had significant effects on Western painting and printmaking. In this regard, Japanese art affected modern art in much the same way that encounters with African and Oceanic art and artifacts did a few decades later. Many late-19th century modern artists not only admired and collected Japanese prints, they derived and adopted both compositional and stylistic approaches from them.

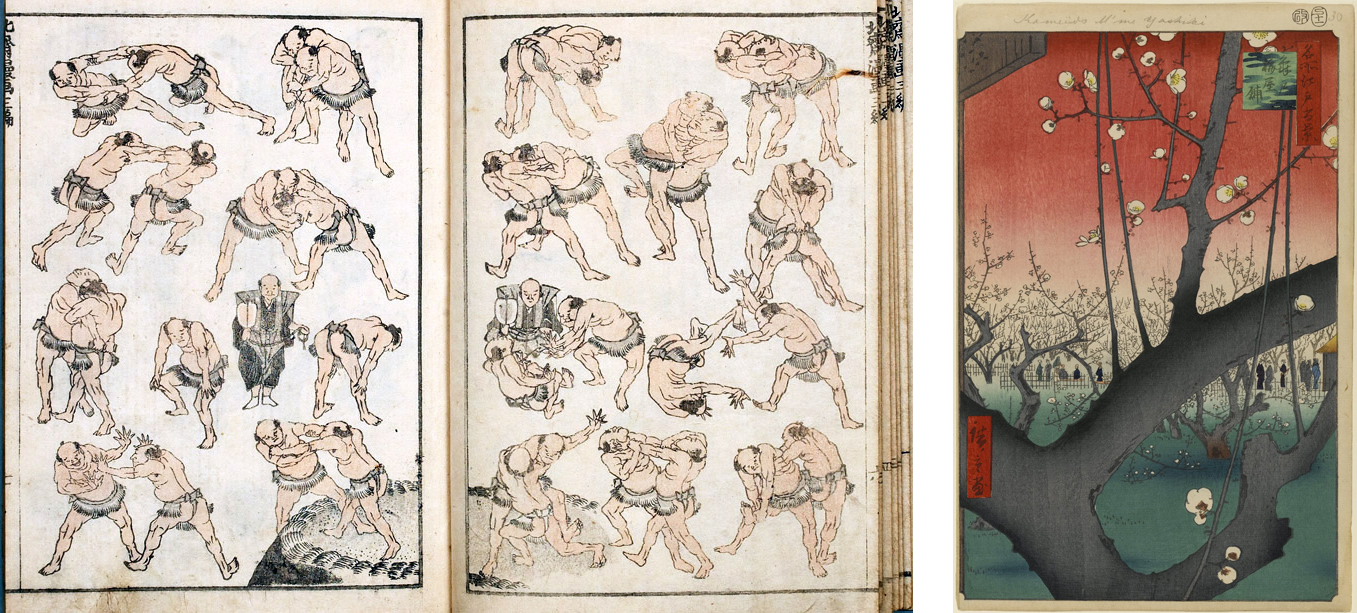

Japanese woodblock prints called ukiyo-e, or “pictures of the floating world,” were a cheap popular art form in Japan during the Edo Period (1615-1868). They were associated with urban entertainment districts (the so-called floating world) in Japan and typically portrayed famous actors, courtesans, and wrestlers, as well as landscape views of well-known sites. Ukiyo-e prints first appeared in Europe as packaging material used to protect valuable imported porcelain objects, but they attracted the interest of European artists and art collectors and were soon imported for their own sake.

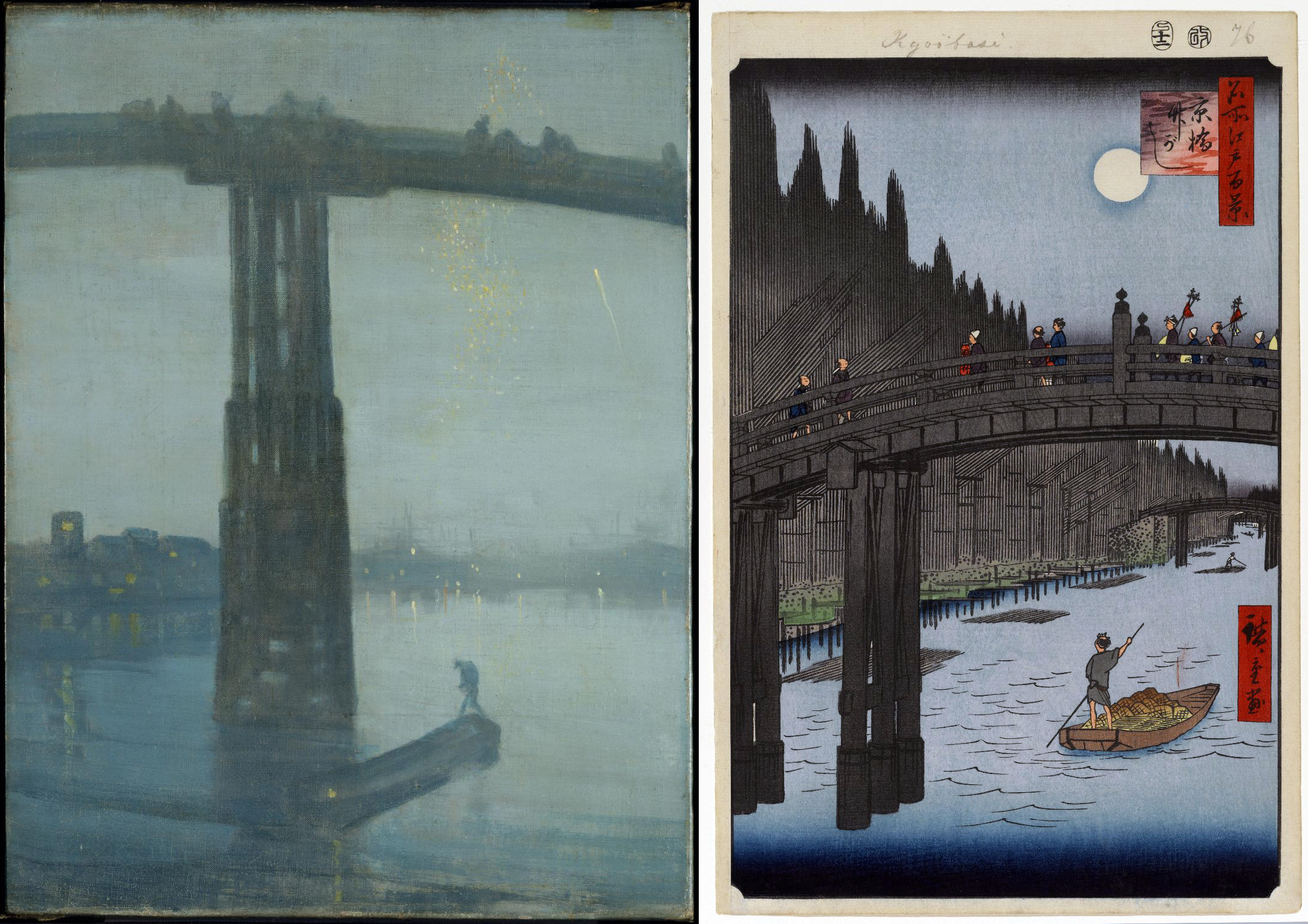

In addition to depicting Japanese decorative objects, Whistler used both subjects and compositional strategies derived from Hiroshige’s prints of notable views in Japan. One of his most innovative and well-known paintings, Nocturne in Blue and Gold: Battersea Bridge, echoes Hiroshige’s Kyobashi Bridge in both its nighttime subject and the abruptly cropped view of the bridge in the foreground. The large areas of flat colors typical of Japanese woodblock prints may also have influenced Whistler’s simplified forms and reduced color range.

The Impressionists were also interested in Japanese prints. After visiting an 1890 exhibition of ukiyo-e prints in Paris, Mary Cassatt employed similar decorative patterns, flattened spaces and simplified figures in a series of color etchings that includes The Letter. Cassatt’s favored subjects, women in domestic interiors playing with children or grooming themselves, were common in ukiyo-e prints, a fact that undoubtedly contributed to her interest in them.

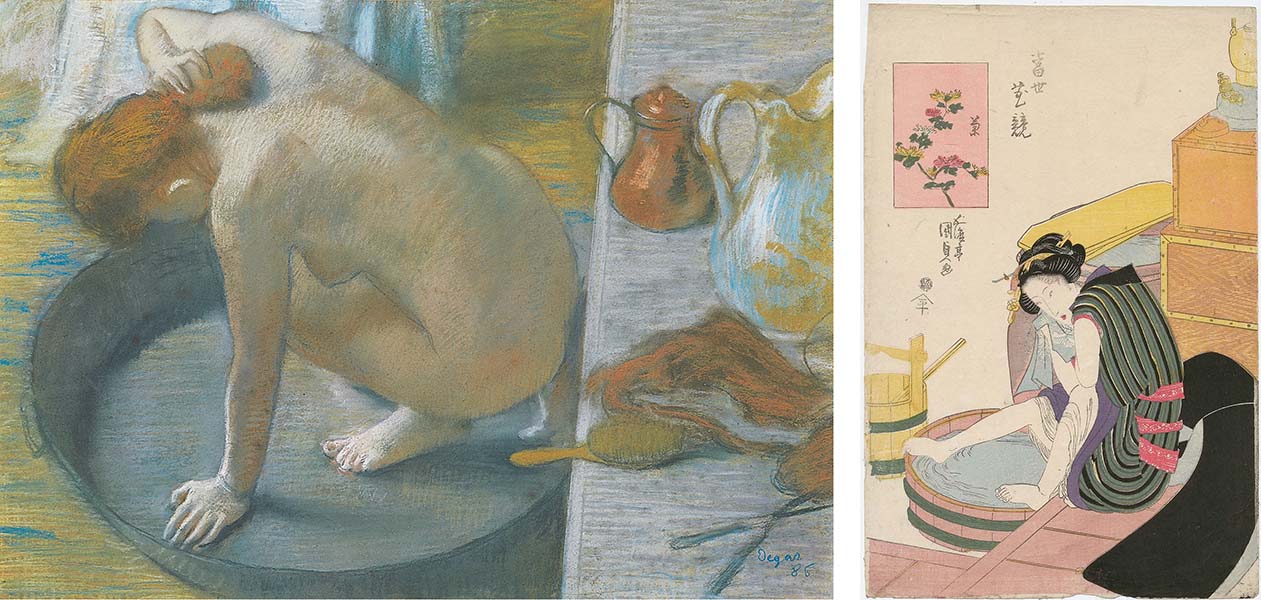

Cassatt’s friend Edgar Degas used Japanese compositional devices to depict women bathing. In The Tub a woman sponging her neck is shown from an elevated vantage point that emphasizes the flat shapes and patterns created by her body and the surrounding objects. The curve of the tub is continued in the woman’s back, while the vertical of her left arm parallels the edge of the shelf on the right side of the painting. Thus, although Degas uses traditional chiaroscuro shading to define three-dimensional forms, abstract pattern and surface design dominate the image, flattening the space and rendering it ambiguous.

Like Degas’ The Tub, Kunisada’s Chrysanthemum shows a bathing woman surrounded by ordinary household objects — note the water heater and scrub brush in the upper right corner. Although the viewing angle is not as high as that in Degas’ work, we see the woman from above, and Kunisada uses the space and objects surrounding her to construct a visual frame for the figure rather than clearly defining an interior space. The repetition of colors and simplified shapes creates a strong surface pattern, as does the lack of chiaroscuro shading.

Among the Post-Impressionists, van Gogh was especially passionate about Japanese art and traditions, although his understanding of Japanese culture was limited and often more personal fantasy than based on real knowledge. He amassed a collection of hundreds of Japanese prints, and they influenced the development of his style, notably his vivid colors, simplified planar forms, and use of decorative surface patterns. In 1888 he wrote his brother Theo, “All my work is based to some extent on Japanese art . . .”

Audio recording of Japonisme (con’t) segment:

Gauguin borrowed directly from Japanese art early in his eclectic and wide-ranging embrace of non-Western cultures and art forms. The bright colors and flat forms of his cloisonnist paintings were greatly indebted to Japanese prints. In Vision after the Sermon Gauguin used two specific Japanese sources. The figures of Jacob and the angel in the upper right are derived from Hokusai’s prints of sumo wrestlers, while the overall composition with its flat red ground and abruptly arcing tree branch echoes Hiroshige’s woodblock print of a blossoming plum tree, a print van Gogh also copied.

Like many artists associated with Art Nouveau, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec was greatly affected by Japanese art and design. His posters, such as the one for a café-concert club called Divan Japonais, show the strong influence of Japanese prints of Kabuki actors in their flat forms, powerful contour design, and dramatic use of black shapes. Unlike the paintings we have looked at thus far in this essay, Toulouse-Lautrec’s posters served a similar role to that of the Japanese woodblock prints; they were a cheap, mass-produced form of publicity for the entertainment industry.

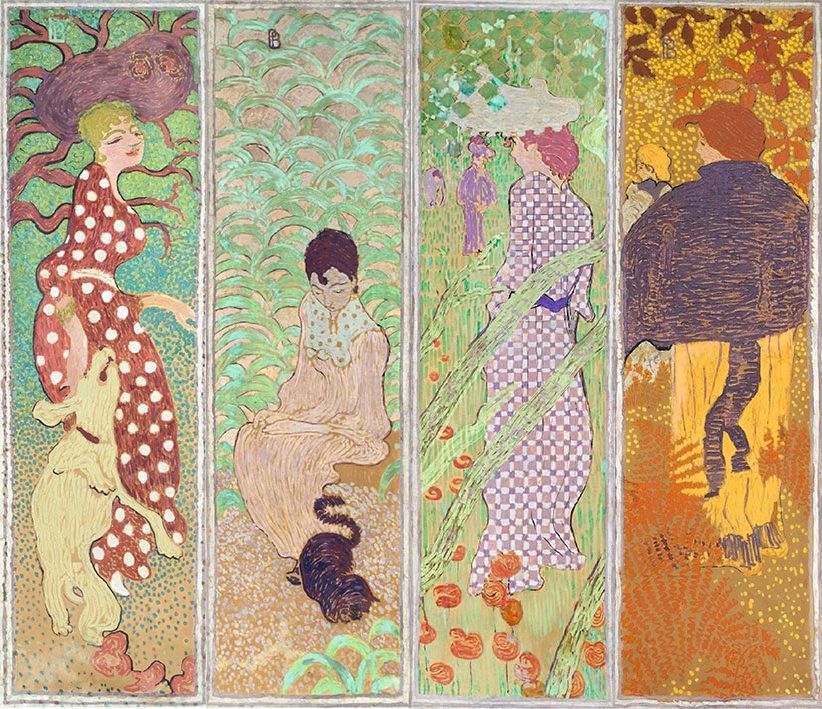

The Nabis, a group of French Post-Impressionist artists affiliated with both Pont-Aven and Symbolism, were great admirers of Japanese art. They were dedicated to the decorative arts and closely associated with Siegfried Bing’s gallery Maison de l’Art Nouveau. In addition to creating paintings, they designed many decorative objects including folding screens and stained glass windows.

Pierre Bonnard, the most Japanese-influenced of the group, painted a set of four narrow vertical panels, initially intended to be part of a Japanese-style folding screen, showing women in stylized garden settings. The subject as well as the detailed patterns and flat decorative forms were directly inspired by Japanese prints and painted screens. His later paper lithograph screen, Nannies’ Promenade, is even more noticeably influenced by Japanese design in its diagonal composition and its use of a restricted color range and patterned silhouettes on an expanse of white paper.

Japanese art had significant effects on both Western decorative arts and the evolution of new artistic styles associated with Modern art. The distinctive qualities of Japanese art — decorative use of color, surface patterning, and asymmetrical compositions — offered striking new approaches to modern artists developing alternatives to the Western tradition of naturalistic representation.

Excerpted and adapted from: Dr. Charles Cramer and Dr. Kim Grant, “Japonisme,” in Smarthistory, June 14, 2020, https://smarthistory.org/japonisme/.

All Smarthistory content is available for free at www.smarthistory.org

CC: BY-NC-SA