17 Chapter 9 – Mary Cassatt

Hannah Martin

Audio recording of the full chapter can be found here: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1OERGIi2kqFSrUjbxzmo0lkP-M-0IozHX/view?usp=sharing

Mary Stevenson Cassatt was an American painter living in France for most of her adult life and up until her death in 1926 at age eighty-two. She was very involved in the Impressionist movement and one of only two women who officially showed art in the exhibits in France during the Impressionist era, and the only American in this group at the beginning.[1] She is famous for her uncommon art of the Impressionist era, focusing on portraits – mostly of mothers and their children – rather than the landscape and street scenes that were so common among Impressionists at the time. As she experimented with many different subjects, she most often depicted women without any of the men that were in their lives, but with their children instead. Many of her artworks only portrayed children or only women; rarely did she paint a portrait of a woman with her husband or a lover. Cassatt was never interested in the lovey-family-oriented kind of life she portrayed through her art but painted it to “not only elucidate but celebrate and pay tribute to the woman’s expected role during Cassatt’s lifetime.” [2] That being said, she still had love for her family, but she was never interested in having one of her own.

Once in France, she studied and copied the great works of art at the Louvre for practice and took private lessons from Ecole des Beaux-Arts because women still weren’t allowed to attend the school.[4] She trained under French artist Jean-Leon Gerome who greatly influenced her later style of painting. He was known for his “eastern influences in his art and his hyper-realistic style” [5] He used bold colours and interesting patterns in his work; many of Cassatt’s paintings had similar patterns, though her patterns were looser and more in the stroke of the brush rather than in the intricate patterns Gerome was painting. That being said, it was too early at this point to call her style “Impressionist” because it was about ten years too early.

In 1868, Mary Cassatt finally got a piece of art in the Paris Salon (one of the most influential events in the art of the Western world that ran from about 1748 to 1890). The painting was called A Mandolin Player but because of her father’s disappointment in her life choices, she signed it under the name Mary Stevenson [6] instead of Mary Cassatt. This is “one of only two paintings from the first decade of her career that can be documented today” according to the Mary Cassatt Biography on marycassatt.org.[7] This piece of art got her in with the famous artists of the Salon where she submitted work for many years until she quit working with the Salon. For one thing, she became bored from the strict guidelines for the artwork, but she also refused to flirt and sleep with the art jurors to get positive responses to her art, as this was a common practice for the women artists who weren’t related to the men by blood or marriage; unfortunately her lack of a man (or want for a man) in her life made it very difficult for her to move up in the Salon.

By the time the 1870s came around, Mary Cassatt had become successful with the Salon but wanted to do something with her art that was more colourful and interesting. One day, she walked past a window and saw the bright pastel works of Edgar Degas, and once wrote to her friend: “I used to go and flatten my nose against that window and absorb all I could of his art. It changed my life. I saw art then as I wanted to see it.” The work inspired her, and in 1877, Degas stopped by her studio to invite her to an exhibit with a group called the Impressionists. Shortly before this, she began to experiment with colour and accuracy that wasn’t quite flattering, which ultimately brought critique and the rejection of a few pieces in the Salon. This new way of art, later called Impressionism, fascinated Cassatt and the success of the group’s fourth exhibit pushed her status through the roof (as much as a woman’s status could elevate at this time). One of her most famous pieces at this time was called Little Girl in a Blue Armchair and was thought to have been worked on by Edgar Degas as well as Mary Cassatt. [8] In 1879, the Impressionists held an exhibit that ended up being their most successful one to date. She displayed eleven works but was criticized for “her colours being too bright” and her portraits were “too accurate to be flattering to the subjects”. [9] She continued to work on Impressionism until 1886 when she moved to a simpler approach and ultimately no longer associated with any art movement in particular.

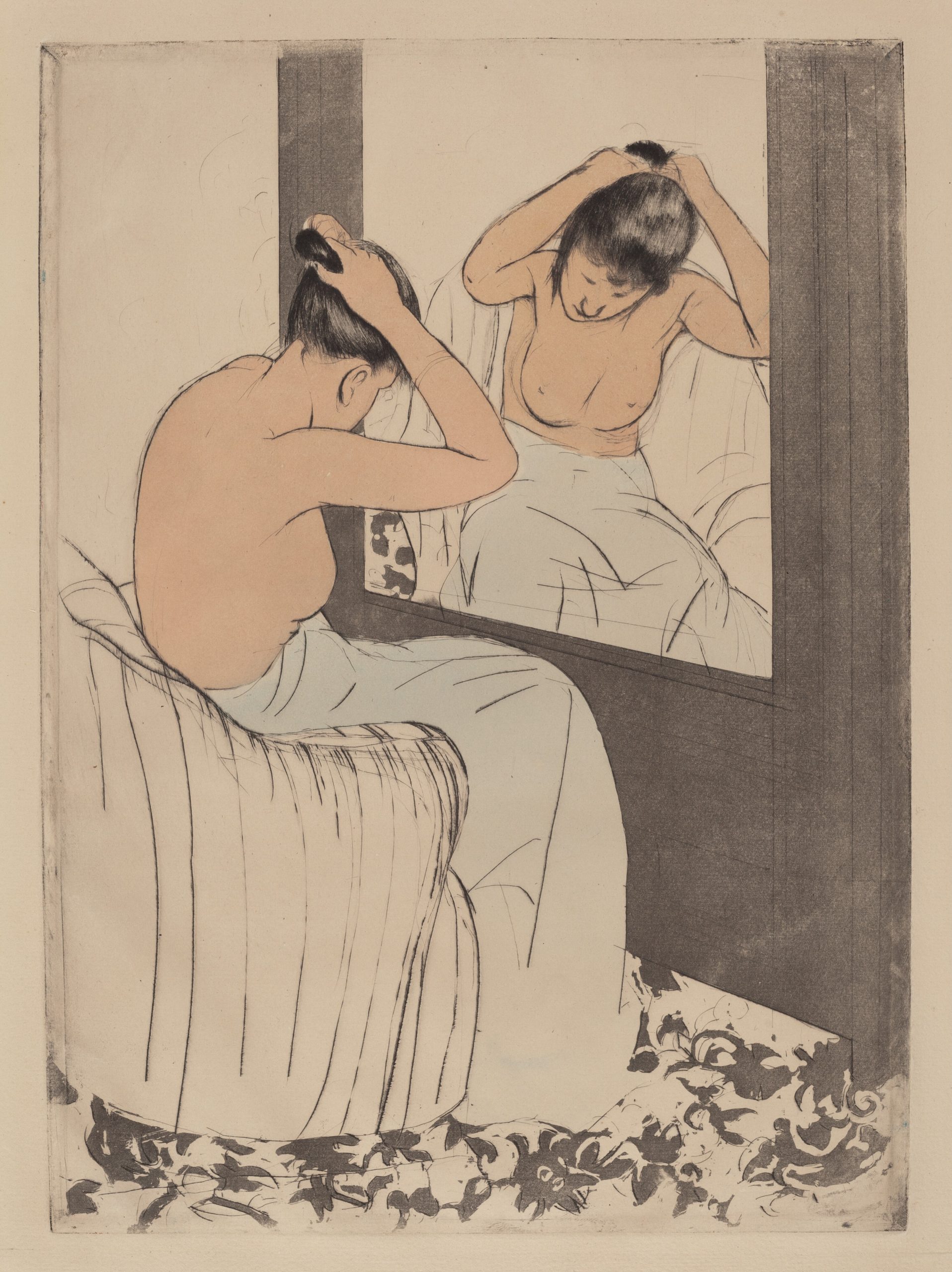

In 1891 after a few years of experimentation, she came across a form of art called Ukiyo-e, a popular form of Japanese printmaking from the Edo period of Japan, often portraying traditional Kabuki actors and other aspects of traditional Japanese culture. [10] It was relatively simple in its way of creation and its style; it is created by carving the design into a woodblock and then pressing it onto paper. Her two most famous Ukiyo-e works were Woman Bathing and The Coiffure. Mary’s most successful and productive time was during the 1890s. She kept in contact with a few of the old Impressionists she worked with in the past and supported them the best she could by buying their artwork and was an advisor to many major art collectors. Her fame rose very slowly in the United States, but she was always overshadowed by her older brother, the president of the Pennsylvania Railroad.

Even though she was pressured by many different parts of her society – like her unsupportive father and the pressure from male colleagues – she brought so many new ideas to the table and pushed back against the societal norms of the time period she grew up in. Her art reflected the life she was most interested in: one with no man present to control or take the spotlight from her. She inspired other artists to not stay stuck to the confines of one particular movement or style and has helped push the women’s suffrage movement forwards by donating her art funds to these organizations. Mary Cassatt was one of the most incredible artists in her time period but is still forgotten because of the lack of study of female artists; great art needs to be recognized and we should start with the incredible art of the women who were left out of history books.

- F. “Mary Cassatt.” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago (1907-1951)20, no. 9 (1926):125-26. Accessed October 16, 2020. https://www-jstor-org.ezproxy.ardc.talonline.ca/stable/4114190 ↵

- Charlotte Davis, “Mary Cassatt: An Iconic American Impressionist,” The Collector, April 21, 2020, https://www.thecollector.com/mary-cassatt/ ↵

- “Mary Cassatt Biography.” Biography, last modified June 19, 2020, https://www.biography.com/artist/mary-cassatt ↵

- “Mary Cassatt Biography.” Biography, last modified June 19, 2020, https://www.biography.com/artist/mary-cassatt ↵

- Charlotte Davis, “Mary Cassatt: An Iconic American Impressionist,” The Collector, April 21, 2020, https://www.thecollector.com/mary-cassatt/ ↵

- “A Mandolin Player.” The Famous Artists, Accessed October 12, 2020, http://www.thefamousartists.com/mary-cassatt/a-mandoline-player ↵

- “Mary Cassatt Biography.” Mary Cassatt, accessed October 12, 2020, https://www.marycassatt.org/biography.html ↵

- Abigail Yoder, “The Artistic Friendship of Mary Cassatt and Edgar Degas,” Saint Louis Art Museum, last modified April 20, 2017, https://www.slam.org/blog/the-artistic-friendship-of-mary-cassatt-and-edgar-degas ↵

- “A Mandolin Player.” The Famous Artists, Accessed October 12, 2020, http://www.thefamousartists.com/mary-cassatt/a-mandoline-player ↵

- “Art of the Pleasure Quarters and the Ukiyo-e Style,” Department of Asian Art, The Met, accessed October 13, 2020, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/plea/hd_plea.htm ↵

- “A Mandolin Player.” The Famous Artists, Accessed October 12, 2020, http://www.thefamousartists.com/mary-cassatt/a-mandoline-player ↵