8 Chapter 6 – French Realism

France

Megan Bylsma

By the end of this chapter you will be able to:

- Explain the concept of Realism

- List Realism’s principle schools and artists (Barbizon, Daumier, Courbet, Bonheur,

Millet, etc.) - Identify the work of Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot

- Discuss Landscape painting in France in the mid-1800s

- Identify the works and philosophy of Honoré Daumier

- Identify the works of Gustave Courbet

Audio recording of chapter opening:

Audio recording of the full chapter can be found here: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1SrFaITPpraZrRTnVWNtJo2ObOT5g5DBt/view?usp=sharing

Remember how before Disney’s remake of The Lion King came out in 2019, so many people were saying it was a ‘live action’ remake?

It was a pretty common statement and because of the realism in the movie trailers and the film stills, a lot of people didn’t question the phrase. But they should have, because was The Lion King filmed with real lions and hyenas and warthogs? Of course not. Therefore, it really wasn’t a ‘live action’ film – it was a film that was meant to look like real animals created through a variety of computer, CGI, and Artificial Intelligence animation. No live animals were used in the film, which means that while it was meant to look like it was real (although it may have spent more time in the Uncanny Valley than at Pride Rock in that regard) it wasn’t reality. It, like its 1994 traditionally animated predecessor, was simply the creation of the filmmakers (with a little extra help from AI this time around).

Art History also had its troubles with reality falsely so called. Consider this painting by Eugene Delacroix – Women of Algiers in Their Apartment from 1834:

Delacroix told everyone who would listen when they came to see it at the 1834 Paris Salon that it was a depiction of reality; that he had gone into a harem during his trip to Algeria and had painted this based on the sketches he had created while there. The Salon attendees were enthralled by this vision of the real experiences of those in the Orient and his painting was a real favorite. A painter who would later turn the art of painting on its head, Paul Cezanne, was intoxicated by the intense colours, while other viewers were enraptured by the exotic theme and intimate scene.[1] To have all their Orientalising desires fulfilled and proven true by this documentation of a harem was like finding treasure. The image of non-European women – sexually passive, indolent, un-industriously passing the time rather than working or reading or otherwise filling their day with activity – is how those in the Occident (Europe) viewed those in the Orient (Asia, India and Africa) and to have it laid out in such a beautiful composition was highly satisfying. It was like being told that French culture and society was the positive to the North African negative. And everyone likes it when their secret suspicions of superiority seem to proven to be correct. Obviously, it could be argued, this showed reality because it confirmed their biases.

However, just like The Lion King from 2019 wasn’t actually real, even though people said it was and it looked like it was, so Delacroix’s painting isn’t Realism, even though people might say it is and it looks like it might be. First, there is the issue with Delacroix’s story. He said he was given permission to enter an Algerian man’s private harem. The term ‘harem,’ although highly sexualized and used to express both sexuality and a kind of ownership-like dominance in Western culture, was in reality quite simply a word to denote a place set aside for the women of an Islamic household. Usually only women were in that part of the house, and if men were allowed it would have only been male members of that household. In Islamic architecture the entry-ways and windows were frequently designed to maximize light and air-flow but block out prying eyes, as the act of looking could be considered intrusive, ill-advised, or even malicious. It would have been considered quite improper for a man, who was not related to the women in Delacroix’s painting, to see these women in such an intimate setting and state of dress. Because Islamic culture has such strongly held beliefs about seeing and being seen it casts doubt on Delacroix’s story that he was given permission by the man of the house to enter the women’s quarters to sketch them. It is unlikely that his story is entirely true, but his fellow Salon-goers back in Paris didn’t know that and saw his painting as a reality.

Which brings us to the question of what is Realism? Listening to Delacroix’s story, one might be tempted to say his painting of these Algerian women is Realism. It looks like its true and the artist said it was real. And one might be tempted to say that The Lion King is Realism too. But both of those temptations would lead you down the wrong path.

Realism, with a capital ‘R’, is something very specific. Just like Romanticism with a capital ‘R’ is something very specific. A painting that is a Realist painting might not look ‘real’ to the photo-trained eyes of a 21st century viewer – it might look like a painting and therefore be labelled something else. (And, while we’re on the topic – a painting that looks like it could be a photograph might seem to be something that could be called Realism (because it looks ‘real’) but that’s not capital-‘R’-Realism; that’s just a painting aesthetic that recreates what a camera can do.) But Realism wasn’t about recreated reality on a canvas with the only goal for things to look like a replica of the original objects. Realism-with-a-capital-‘R’ was about capturing reality of existence. Realism paintings look like paintings, but they don’t Romanticize their subject – making them more dramatic and emotionally impactful than they really are. Realism looked to faithfully reproduce the subject as a piece of a larger social picture.

Audio recording of Realism segment (con’t):

Whereas Romanticism was about emotion, Realism was about logic. Consider the sitcom The Big Bang Theory – two characters, for much of the show’s run, live in the same apartment. One is logical and makes decisions based on eliminating as much emotion as possible. The other is emotional and makes decisions based less on logic and more on how he feels about things. Sheldon, the logical one, tends to react to Leonard, the emotional one, and in many ways Leonard serves as the impetus for Sheldon’s growth and interaction with new ideas or concepts beyond his narrower focus of interest. In many ways this could be a crude illustration of the relationship between Romanticism and Realism. Whereas Romanticism was an emotional reaction to the non-reality based logic and duty of the Neo-Classical (not unlike Leonard’s emotional response to his analytical mother), once Romanticism gained momentum the emotional indulgence of the genre was seen as too decadent or self-serving for some artists. In reaction to the emotional play of Romanticism that seemed to increasingly turn inward, the Realists rejected the inward gaze and made a declaration to depict the reality of life without the dynamic and manipulative use of emotion. The Realists believed it was their duty to mirror the world back to the viewer and to not allow the viewer to hide in an exotic and escapist fantasy. The Realists were not interested in diving into metaphors of the Classical Era to express grandiose philosophies of noble simplicity and calm grandeur. Nor were they interested in theatrics and self-satisfaction. The Realists wanted viewers to be presented with a social reality that they could not ignore. They wanted to smack the public in the face with the plight and existence of others. However, these two art movements were roommates, so to speak, in the same house at the same time, and were the opposites needed to balance the whole; they occurred at the same time in France and reacted to each other in the Salons. It could be argued that Leonard, from The Big Bang Theory, could have functioned relatively fine and would have lived a fairly full and normal life without Sheldon; however, the same might not be so successfully argued regarding Sheldon in the absence of Leonard. The aggravation of Leonard’s perpetually emotional existence aggravated Sheldon enough to create impetus for change, however reluctantly, especially in the beginning. Thus it was with Romanticism and Realism – Romanticism existed before Realism and could have continued to flourish without Realism, but Realism was aggravated into development by the emotional and dramatic existence of Romanticism, eventually eclipsing it’s emotional counterpart in popularity and evolution.

There is a genre of painting that can sometimes be mistaken for Realism, mostly because its artists always say their work show reality but really its not Realism because then it would be have been rejected from the very institution that created it because it believed the present moment was not heroic enough to demand valued attention. The genre is Academic Painting and it’s a genre that is rarely talked about too in depth in art history texts. At least, if it is talked about it, they don’t mention its as Academic because…Academic painting and its privileged artists just isn’t where it’s at these days. Art History tends to tell the story of the spunky, if not at least slightly dysfunctional, underdogs of art. But in telling these stories it often makes them big and showy and attention grabbing by virtue of their conflict-driven storylines. Academic Art has less conflict, at least on the surface. The Academic artists’ fight weren’t against mainstream art culture, so their conflicts seem petty and individualistic by comparison. And the artists of the Academy didn’t seem to function on the outskirts of societal norm so at first glance they were not plagued by the same foibles as the anti-establishment artists of the day. I say at first glance, because almost anyone, upon closer inspection, shows sign of dysfunction and drama. But don’t let the present-day silence around the Academic art of the 1800s fool you – they were the big dogs of their time.

An Academic painter who would swear he only painted historical reality – in fact he said accuracy was of the highest importance to him – was Paul Delaroche. Closer scrutiny of Delaroche shows two things: fact maybe wasn’t as important to him as he may have stated and he had his own secrets.

Let’s start with the secrets (that probably weren’t so secret). “Paul Delaroche” was not the name Delaroche was born with. His original name was Hippolyte De La Roche. If you have recently read or watched Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream or if you are up on your Greek mythology you may recognize the name Hippolyte, also called Hippolyta. She features in Greek myth as the Queen of the Amazons, and also made her way to the big screen in 2017 in Wonder Woman. Hippolyte, while a female name in Greek myth and in the DC Comics universe, was an acceptable male name in France at this time and Hippolyte De La Roche shared the moniker, at least partially, with his father. However, Hippolyte De La Roche didn’t seem to like it all that much and changed his name to the diminutive ‘Paul’. He also changed the arrangement of his last name from De La Roche to Delaroche. Which may or may not have been a good idea, because de la roche means ‘The Rock’ in French.

Paul “The Rock” Delaroche, became an Academic painter fairly early in his artistic career, exhibiting his historical paintings in the yearly Salon and eventually scoring a coveted life-time membership in the Academy. He felt that accuracy was his highest calling and prided himself on researching details of fashion and environment for his paintings. However, the critical eye of history has come to see that Delaroche took artistic liberties in ways that have no excuse if the artist is sworn to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, so help them.

Audio recording of Delaroche segment (con’t):

One of his most cited examples of artistic liberty winning out over honest representation is in his painting, The Execution of Lady Jane Grey. Decisions were made in this painting that created a more dramatic feeling, and here, as in many of his other works, he was guilty of basing his paintings on superstitions and urban legends, rather than careful research into the truth. In this execution scene a young, blindfolded woman in a kind of dungeon interior space and on a platform is being guided to an execution block. It is important to know that this is a painting depicting the beheading of Lady Jane Grey. But what is the story really? We may know Lady Grey as a flavour variation of Earl Grey tea, but Lady Grey was actually a real person. She was a English noblewoman and was put to death for treason in the 1500s. She is also known as the Nine Day Queen of England. She was the cousin of the fifteen year old king of England, King Edward VI. As the young king lay dying, he declared Lady Jane Grey his successor and new Queen of England because he knew his half-sisters Mary and Elizabeth were scheming for the throne. One, a Roman Catholic, wanted the throne to take the now Protestant country back for the Catholic faith and both were illegitimate children of Edward VI’s father. Edward knew that Lady Jane Grey, a year older than himself, was considered to be one of the best educated women in the country, was a devoted Protestant, and was a woman who lead his country in a way he would appreciate. Lady Grey was declared de facto queen. But the sisters kept their scheming up and Mary used popular opinion to help her secure her desires. With the popular voice seeming to side with Mary, the Council decided to crown Mary and arrested Jane for treason. First her husband, and then she was executed. She was barely 17.

Looking at the painting, we might ask, “Where’s the lie?” In this case, as is often the way, its the details that reveal the truth of things. While the French traditionally used raised platforms to stage executions of noblepersons, especially during and after the French Revolution, the British did not – they used the bare grass of the Tower Green outside the Tower of London. As well, the French would perform beheadings in indoor spaces like dungeons, but the British tended to do it outside and in the open (obviously, as they preferred that specific grassy space for executions). However, there may be some truth to the depiction of Lady Jane Grey groping with her hand for the block and being guided by another – this event is said to have occurred after she blindfolded herself and then cried out in a panic unable to find the block. However, even with its truthful elements this historical painting is not a depiction of reality. It is the retelling of a historical story. Realism never shows history as it was believed to have happen; Realism depicted the present moment as it was observed to be.

The Royal Academy supported the age-old belief that art should be instructive, morally uplifting, refined, inspired by the classical tradition, a good reflection of the national culture, and, above all, about beauty.

But trying to keep young nineteenth-century artists’ eyes on the past became an issue!

The world was changing rapidly and some artists wanted their work to be about their contemporary environment—about themselves and their own perceptions of life. In short, they believed that the modern era deserved to have a modern art.

The Modern Era begins with the Industrial Revolution in the late eighteenth century. Clothing, food, heat, light and sanitation are a few of the basic areas that “modernized” the nineteenth century. Transportation was faster, getting things done got easier, shopping in the new department stores became an adventure, and people developed a sense of “leisure time”—thus the entertainment businesses grew.

In Paris, the city was transformed from a medieval warren of streets to a grand urban center with wide boulevards, parks, shopping districts and multi-class dwellings (so that the division of class might be from floor to floor—the rich on the lower floors and the poor on the upper floors in one building—instead by neighborhood).

Therefore, modern life was about social mixing, social mobility, frequent journeys from the city to the country and back, and a generally faster pace which has accelerated ever since.

How could paintings and sculptures about classical gods and biblical stories relate to a population enchanted with this progress?

In the middle of the nineteenth century, the young artists decided that it couldn’t and shouldn’t. In 1863 the poet and art critic Charles Baudelaire published an essay entitled “The Painter of Modern Life,” which declared that the artist must be of his/her own time.

Excerpted and adapted from: Dr. Beth Gersh-Nesic, “A beginner’s guide to Realism,” in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, https://smarthistory.org/a-beginners-guide-to-realism/.

All Smarthistory content is available for free at www.smarthistory.org

CC: BY-NC-SA

By the early 1800s, the Academy was fully re-established as the center of the mainstream art world in France. However, they began to recognize that their obsessive focus on Neo-Classicism to the exclusion of all new art genres was starting to damage their reputation as the purveyors and trainers of the best and most innovative artists and so they began to shake things up a bit. But keep in mind they were an institution built on now-hallowed traditions, so their shake up was subtle. Basically, landscape painting was moved up the hierarchy and a special category in the yearly art show was created specifically for landscape pieces. This might have been a radical move, if it wasn’t for the fact that the Academy had done this to shore up interest in the Neo-Classical style. The new category was the paysage historique (historic landscape) and made landscapes eligible for consideration in the Prix de Rome awards – awards given to the artist of the best painting in a genre category in the show. The prize came, complete with a gold medal, with a paid stay in Rome at the French Academy there. As the most prestigious award the Academy could give out, the creation of the paysage historique category created a new competition field and young artists flocked to the Louvre to look at the Dutch and Flemish landscapes (the Dutch and Flemish had been into landscape centuries before the Parisian art scene gave them any serious thought) and to learn about this previously undervalued genre of painting. It also meant that viewers flocked to the Salon to view the newly created landscapes. By 1835 landscape paintings made up over a quarter of the art displayed at the Salon. Suddenly landscapes were cool and everybody was talking about them.

Historical Landscapes as an Academy genre paved the way for interesting developments in the art world. As landscape paintings took the Salon walls by storm (pun intended), the focus on including historical elements remained necessary. But as artists began to become more and more skilled at rendering the landscape in pleasing ways, and became more and more influenced by the Dutch, Flemish, and British landscape artists, the paysage historique began to slowly give way to another kind of landscape – a landscape of the present without much, or any, historical significance. Neo-Classicism may have been the the clinging goal for the Academy to change its mind about landscape painting, but it may have been a final nail in the coffin of the aging art style.

Audio recording of Corot part 1 segment:

Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot

Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot was a quiet young man who didn’t seem to excel at much of anything. Apprenticed to a draper after his schooling came to an end, he was bored and hated the business end of the job. But to please his father he continued in the job until he was ready to seek permission to pursue art as a career. Receiving that permission and a small yearly allowance, the artist, now in his mid-twenties, set up a studio and began to paint landscapes.

During the period when Corot acquired the means to devote himself to art, landscape painting was on the upswing and generally divided into two camps: one―historical landscape by Neoclassicists in Southern Europe representing idealized views of real and fancied sites peopled with ancient, mythological, and biblical figures; and two―realistic landscape, more common in Northern Europe, which was largely faithful to actual topography, architecture, and flora, and which often showed figures of peasants. In both approaches, landscape artists would typically begin with outdoor sketching and preliminary painting, with finishing work done indoors. Highly influential upon French landscape artists in the early 19th century was the work of Englishmen John Constable and J. M. W. Turner, who reinforced the trend in favor of Realism and away from Neoclassicism.[2]

For a short period between 1821 and 1822, Corot studied with Achille Etna Michallon, a landscape painter of Corot’s age who was a protégé of the painter Jacques-Louis David and who was already a well-respected teacher. Michallon had a great influence on Corot’s career. Corot’s drawing lessons included tracing lithographs, copying three-dimensional forms, and making landscape sketches and paintings outdoors, especially in the forests of Fontainebleau, the seaports along Normandy, and the villages west of Paris such as Ville-d’Avray (where his parents had a country house).[3] Michallon also exposed him to the principles of the French Neoclassic tradition, as espoused in the famous treatise of theorist Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes, and exemplified in the works of French Neoclassicists Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin, whose major aim was the representation of ideal Beauty in nature, linked with events in ancient times.

Though this school was declining in public popularity, it still held sway in the Salon, the foremost art exhibition in France attended by thousands at each event. Corot later stated, “I made my first landscape from nature…under the eye of this painter, whose only advice was to render with the greatest scrupulousness everything I saw before me. The lesson worked; since then I have always treasured precision.”[4] After Michallon’s early death in 1822, Corot studied with Michallon’s teacher, Jean-Victor Bertin, among the best known Neoclassic landscape painters in France, who had Corot draw copies of lithographs of botanical subjects to learn precise organic forms. Though holding Neoclassicists in the highest regard, Corot did not limit his training to their tradition of allegory set in imagined nature. His notebooks reveal precise renderings of tree trunks, rocks, and plants which show the influence of Northern realism. Throughout his career, Corot demonstrated an inclination to apply both traditions in his work, sometimes combining the two.[5]

With his parents’ support, Corot followed the well-established pattern of French painters who went to Italy to study the masters of the Italian Renaissance and to draw the crumbling monuments of Roman antiquity. A condition by his parents before leaving was that he paint a self-portrait for them, his first. Corot’s stay in Italy from 1825 to 1828 was a highly formative and productive one, during which he completed over 200 drawings and 150 paintings.[6] He worked and traveled with several young French painters also studying abroad who painted together and socialized at night in the cafes, critiquing each other and gossiping. Corot learned little from the Renaissance masters (though later he cited Leonardo da Vinci as his favorite painter) and spent most of his time around Rome and in the Italian countryside.[7] The Farnese Gardens with its splendid views of the ancient ruins was a frequent destination, and he painted it at three different times of the day.[8] The training was particularly valuable in gaining an understanding of the challenges of both the mid-range and panoramic perspective, and in effectively placing man-made structures in a natural setting.[9] He also learned how to give buildings and rocks the effect of volume and solidity with proper light and shadow, while using a smooth and thin technique. Furthermore, placing suitable figures in a secular setting was a necessity of good landscape painting, to add human context and scale, and it was even more important in allegorical landscapes. To that end Corot worked on figure studies in native garb as well as nude.[10] During winter, he spent time in a studio but returned to work outside as quickly as weather permitted.[11] The intense light of Italy posed considerable challenges, “This sun gives off a light that makes me despair. It makes me feel the utter powerlessness of my palette.”[12] He learned to master the light and to paint the stones and sky in subtle and dramatic variation.

During his two return trips to Italy, he visited Northern Italy, Venice, and again the Roman countryside. In 1835, Corot created a sensation at the Salon with his biblical painting Agar dans le desert (Hagar in the Wilderness), which depicted Hagar, Sarah’s handmaiden, and the child Ishmael, dying of thirst in the desert until saved by an angel. The background was likely derived from an Italian study.[13] This time, Corot’s unanticipated bold, fresh statement of the Neoclassical ideal succeeded with the critics by demonstrating “the harmony between the setting and the passion or suffering that the painter chooses to depict in it.”[14]

Historians have divided Corot’s work into periods, but the points of division are often vague, as he often completed a picture years after he began it. In his early period, he painted traditionally and “tight”—with minute exactness, clear outlines, thin brush work, and with absolute definition of objects throughout, with a monochromatic underpainting or ébauche.[15] After he reached his 50th year, his methods changed to focus on breadth of tone and an approach to poetic power conveyed with thicker application of paint; and about 20 years later, from about 1865 onwards, his manner of painting became more lyrical, affected with a more impressionistic touch. In part, this evolution in expression can be seen as marking the transition from the plein-air paintings of his youth, shot through with warm natural light, to the studio-created landscapes of his late maturity, enveloped in uniform tones of silver. In his final 10 years he became the “Père (Father) Corot” of Parisian artistic circles, where he was regarded with personal affection, and acknowledged as one of the five or six greatest landscape painters the world had seen, along with Meindert Hobbema, Claude Lorrain, J.M.W. Turner and John Constable. In his long and productive life, he painted over 3,000 paintings.[16]

Audio recording of Corot part 2 segment:

Though often credited as a precursor of Impressionist movement art practices, Corot approached his landscapes more traditionally than is usually believed. Compared to the Impressionists who came later, Corot’s palette is restrained, dominated with browns and blacks (“forbidden colors” among the Impressionists), along with dark and silvery green. Though appearing at times to be rapid and spontaneous, usually his strokes were controlled and careful, and his compositions well-thought out and generally rendered as simply and concisely as possible, heightening the poetic effect of the imagery. As he stated, “I noticed that everything that was done correctly on the first attempt was more true, and the forms more beautiful.”[17]

Excerpted and adapted from: Wikipedia, (October 6 2020), s.v. “Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-Baptiste-Camille_Corot

Corot was neither a Realist nor a Neo-Classicist. Having trained in Italy and learned to paint en plein air (in the open air) his landscapes looked more real than other French landscape artists’ works had. He was a painter who had a fraught relationship with the Academy due to his love of the landscape. He is sometimes said to be the link between Realism and Impressionism but using Corot as the link between the two is not completely true. He was never a Realist – one who wanted to capture the heroism of his own time; he just wanted to paint landscapes. His focus on landscape painting and his generous spirit with his students pushed landscape painting forward, even as the Academy attempted to hold it back. His later works, influenced by the camera, by practice, and by the good sales of a brushier style, were very silver-y and influenced the next two generations of artists. He used to get into arguments with a young artist named Claude Monet, who also loved the landscape, about the colour to prime one’s canvas. Corot had stopped using the Academy’s traditional dark brownish red grounding and had begun to paint his canvas a silvery grey before he applied his gentle colours. Claude Monet swore by the new synthetic pigment zinc white as a brighter and more effect ground for a colourful painting. The outcome of this argument came years later, when seeing how his own canvases quickly faded to the midtones but Monet’s stayed bright and powerful, he said, “Monet was right.” Of course, as is the way with rivaling friends, he never told Monet so. Besides, Corot never wanted to paint brightly coloured paintings, he just wanted to paint the land.

Audio recording of Barbizon School segment:

The Barbizon School

Calling something a ‘school’ makes it seem like there was an institutionalized and codified training program in a single place. But in the case of the Barbizon School, the word ‘school’ is more in keeping with a paradigm or ‘school of thought’. Barbizon was a small town on the edge of the forest and as landscape painting grew in public popularity and as intermittent plagues broke out in the cities and because new train tracks made travel around France easier, people flocked to small towns like Barbizon to enjoy the landscape. Barbizon is located on the edge of what had previously been the king’s private hunting forest – Fontainebleau – and its unique weather made it a place of dense growth and beautiful scenery. As early as the 1820s artists began to journey to Barbizon to paint the landscape, some moving there permanently as living conditions in Paris worsened. Those who became known as the Barbizon School were most active from around 1830-1870, but saw the most interaction during the Revolution of 1848 – when they left Paris for safety, and then during the cholera outbreak in Paris right after the Revolution of 1848. The artists who frequented Barbizon became known as artists of the Barbizon School, and this is why Corot is sometimes lumped in with the artists of the Barbizon School. He went there occasionally too and was friends with many of the artist we’re about to discuss. But keep in mind, this is not what they would have called themselves. To themselves they were just a loosely grouped bunch of artists who were interested in investigating the same thing – the landscape and the reality of existence.

So what makes a Barbizon landscape different from, say, the Caspar David Friedrich paintings in the previous chapter?

Barbizon paintings don’t have ruins. They aren’t picturesque (strictly speaking). They show quiet corners of rustic France. Not far-flung places in Italy. Or place that look like Italy. Eventually they would also come to be known for their portrayal of simple people living simple lives in the simple landscape. But for the most part, the Barbizon School was all about the landscape.

All landscape all the time.

Théodore Rousseau

Théodore Rousseau was the loudest voice for the call to artists to the outdoors. Some say the forest possessed him. He eventually purchased property in Barbizon and lived there in the later part of his life – but at first he just visited. He and his wife moved into the cottage he purchased in Barbizon and there he lived for most of the rest of his life between trips to Paris for art sales and shows and one disastrous trip to the Alps. Rousseau met with many artists who came to Barbizon and helped them find good painting spots in the woods, taught them how to paint trees, and had in-depth discussions with them about the importance of painting the land. But despite his reputation as a devout landscape painter, he had a serious run of bad luck later in his life. His wife became severely mentally ill and required serious care. His father became destitute and relied on his son for monetary aid. While he and his wife were away from home in search of medical treatment for her mental illness, a young friend of the family who had been staying with them caused his own death in their cottage. Then, during that trip to the Alps, Rousseau caught pneumonia and the consequent weakening of his lungs plagued him the rest of his life. When he returned home he suffered insomnia and the lack of sleep weakened him. Possibly in response to being rejected (yet again) from receiving awards for his work, Rousseau had an undiagnosed but much debated attack of health and became paralyzed. Although he recovered he then suffered a relapse later that year and died, leaving his ill wife in the care of his fellow painter and friend Jean-François Millet.

Melancholy is the over arching theme in his painting, although he sought to paint the landscape as it was.

All his landscapes were rejected from the Academy until after the 1848 Revolution – but under the monarchy? Nothin’. So he quit trying. The lack of publicity at the Salon actually worked to his advantage – he became a legend.

Audio recording of Millet segment:

Jean-François Millet

Jean-François Millet is one of the “founders” of the Barbizon School in rural France. (Although, as a “founder” he was simply one of the artists who spent time in Barbizon and was friends with the other artists there.) Millet is noted for his scenes of peasant farmers and can be categorized as part of the Realism art movement.

One of the most well known of Millet’s paintings is The Gleaners. While Millet was walking the fields around Barbizon, one theme returned to his pencil and brush for seven years—gleaning—the centuries-old right of poor women and children to remove the bits of grain left in the fields following the harvest. He found the theme an eternal one, linked to stories from the Old Testament. In 1857, he submitted the painting The Gleaners to the Salon to an unenthusiastic, even hostile, public.

One of his most controversial, this painting by Millet depicts gleaners collecting grain in the fields near his home. The depiction of the realities of the lower class was considered shocking to the public at the time, even as Realism gained momentum with many artists.

Excerpted and Adapted from: Curation and Revision. Provided by: Boundless.com. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-arthistory/chapter/realism/

License: CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker provide analysis and historical perspective on Jean-François Millet’s The Gleaners.

Retrieved from: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, “Jean-François Millet, L’Angélus,” in Smarthistory, November 27, 2015, accessed October 13, 2020, https://smarthistory.org/jean-francois-millet-langelus/.

All Smarthistory content is available for free at www.smarthistory.org

CC: BY-NC-SA

Millet painted The Sower a year after he moved with his wife to Barbizon. They had moved to escape the cholera epidemics in Paris following the 1848 Revolution and had purchased a tiny cottage at Barbizon. (They lived in that tiny cottage with their nine children.) The Sower is indicative of his early style – loose, rough, and blunt. His work, even when it became more refined, always showed a very unpolished reality. Not a cruel reality, like other artists would, but reality as it existed without any romanticizing of the subject or hiding the plight of the modern peasant in narrative.

This painting has influenced many of the painters in the late nineteenth and twentieth century. Van Gogh especially loved it and did his own version of it.

In The Gleaners, some people see beauty, some see the need for social reform, others see the pain in the bodies of the women’s posture.

All of which was the point. Millet didn’t create his work to show pretty pictures of indolent peasants living a pretty peasant life. Millet was not a “cottagecore aesthetic” artist (obviously, since that term is a strictly 21st century thing, but the concept does need to be stated). His work depicted the poorest of the poor – scraping up the leftovers after the crews have harvested and taken away the bulk. For the women in The Gleaners, if they don’t gather the scraps their families will starve.

The Angelus was originally titled Prayer for the Potato Crop but the American that commissioned never picked it up, so Millet added the steeple and changed the name to The Angelus – which are the first word of the The Angelus prayer – said by Catholics during the Angelus bell (6pm usually, but it can be other times too). The prayer was an evolution of the traditional three Hail Marys said at the 6pm bell. The prayer begins in Latin with Angelus Domini nuntiavit Mariæ – which means the “The Angel told Mary” and is said to remember the Annunciation.

The thing about this painting is that during his lifetime it was simply a good example of his style, but after Millet’s death the value of it went up so dramatically that it caused an uproar.

Even stranger, Salvador Dali, the Surrealist artist who rose to fame at the end of the 1800s and beginning of the 1900s, eccentric man that he was, always felt there was something traumatic about this painting. He felt this so strongly that eventually he used his artistic clout to get the painting x-rayed. He was sure there was something horrible under the paint and that they were not praying over a basket of potatoes, but rather the corpse of a child. (He also said this painting was about sexual repression. But Dali also thought women were secretly praying mantises and that the pose of the praying woman in the painting was evidence of that so it really can’t be put to too many people’s blame if they didn’t take him seriously about the painting needing to be x-rayed right away. He was prone to wildly unusual perspectives about things.)

Here’s the kicker though, as strange as Dali might have been – when they did the x-ray they found that the potato basket was a recent addition. Originally there had been a square/rectangular thing between the couple! Some thought perhaps Dali was correct and it was a baby’s coffin, others felt maybe not so much.

So that is one of the unexplained things regarding this painting. And one of the many unexplained things about Salvador Dali…

Audio recording of Bonheur segment:

Rosa Bonheur

Rosa Bonheur is often lumped in with the Barbizon School artists, but this is simply because she doesn’t fit with the Parisian artists of her time. She unapologetically painted the reality of animals without romanticizing them or loading her paintings with narrative. But she was not a Barbizon painter in any way.

Rosa Bonheur is an interesting figure in art history and an harbinger of changes happening in Parisian society. Raised in an unusual family, Bonheur was educated and given the same opportunities as her male siblings. Her father supported the idea that women could do anything they wanted and should be given the tools to be able to do so. As a child she was unruly and active with little patience for most activities that required sitting still. Subsequently she had a hard time learning to read. Her mother encouraged her to learn by asking her to draw an animal for every letter of the alphabet and Bonheur later said that this was when she began to learn how to draw animals. She could sit still and draw for hours. Later, she was sent to school with her brothers but was expelled a number of times. Then she was apprenticed to a seamstress; which for obvious reasons didn’t go so well. Eventually she had a painter take her on as a pupil and she discovered her great passion in creating art at the age of twelve.

This photo is of Rosa Bonheur from later in the 1800s. Notice her choice of clothing. In the 1800s it was relatively unorthodox for women to wear trousers. In fact, a woman needed a special license to wear things that were considered to be men’s clothing, like trousers, or they could be accused or arrested for cross-dressing (which was a punishable offense in Paris at this time). Bonheur argued that for her work painting, sketching and observing at stockyards and horse fairs and cattle sales, she couldn’t be dragged down in the mud by petticoats, skirts, and bustles. Those types of clothing could create dangerous situations in the event that she needed to move quickly and freely out of the way of an uncontrolled animal. Often the history books make it sound like Bonheur broke the law and created a big scandal with her clothing, but in reality it was simply a matter of applying to the Parisian police for a permit which she was granted. And while her clothing choices would have definitely turned heads in Paris, it is not likely that they ’caused an uproar.’

However, if you look at her photograph again, you will see that she is wearing trousers in a garden – not at a livestock exhibition. Bonheur wore what she wanted, when she wanted to wear it. Obviously, she was a spit-fire throughout her life and while biographical elements of an artist’s life are often not important to relay when discussing their art, in the case of Bonheur a discussion about her private life is in order because of the road she would pave for later female artists.

Women were often only reluctantly educated as artists in Bonheur’s day, and by becoming such a successful artist she helped to open doors to the women artists that followed her.[18]

Bonheur can be viewed as a “New Woman” of the 19th century – her choice of dress only part of that. In her romantic life, she never explicitly stated that she was a lesbian but she is accepted to have been a lesbian; she lived with her first partner, Nathalie Micas, for over 40 years until Micas’ death, and later began a relationship with the American painter Anna Elizabeth Klumpke.[19]

In a world where gender expression was policed, Rosa Bonheur broke boundaries by deciding to wear pants, shirts and ties.[20] She did not do this because she wanted to be a man, though she occasionally referred to herself as a grandson or brother when talking about her family; rather, Bonheur identified with the power and freedom reserved for men.[21] Wearing men’s clothing gave Bonheur a sense of identity in that it allowed her to openly show that she refused to conform to societies’ construction of the gender binary. It also broadcast her sexuality at a time where the lesbian stereotype consisted of women who cut their hair short, wore pants, and chain-smoked. Rosa Bonheur did all three. Bonheur, while taking pleasure in activities usually reserved for men (such as hunting and smoking), viewed her womanhood as something far superior to anything a man could offer or experience. She viewed men as stupid and mentioned that the only males she had time or attention for were the bulls she painted.[22]

Having chosen to never become an adjunct or appendage to a man in terms of painting, she decided that she would lean on herself and her female partners instead. Her partners focussed on the home life while she took on the role of breadwinner by focusing on her painting. Bonheur’s legacy paved the way for other lesbian artists who didn’t favour the life society had laid out for them.[23]

Along with other realist painters of the 19th century, for much of the 20th century Bonheur fell from fashion, and in 1978 a critic described Ploughing in the Nivernais as “entirely forgotten and rarely dragged out from oblivion”; however, that same year it was part of a series of paintings sent to China by the French government for an exhibition titled “The French Landscape and Peasant, 1820–1905”.[24] Since then her reputation has revived and interest in the art and life of this gifted artist grows each year.

Excerpted and adapted from: Wikipedia, (September 19 2020), s.v. “Rosa Bonheur.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rosa_Bonheur

Even without taking her personal life into consideration, she was considered a very odd painter. Most artists, especially female artists, paid attention to the people (especially the Realists) or the landscape. Very few focused on animals in such a realistic way. Unromantically. There’s no double meaning in her painting The Ploughing in the Nivernais. There’s no lion attacking a horse as a metaphor for the monarchy causing violence to the people here. There’s no meaning imbued on these oxen. They’re just really realistic oxen doing a really realistic job. There are people in this painting, but they are really, really not the point. Even their rendering is different than the animals – the humans are painted in a way that makes them look like paintings, whereas the oxen look incredibly real and important.

It’s for this reason that Bonheur is considered a Realist. She painted the present day reality as it existed. However, she doesn’t really fit with the Realists because she’s not actively seeking to portray the everyday hero or the contemporary strength of the day. She is simply painting animals as they are.

The horses in The Horse Fair are pretty nearly lifesize. Which makes for a kind of an overwhelming experience when you see it. Each horse is just a little smaller than reality – which means the canvas is HUGE. It was paintings like this that made her get the license to wear pants.

This painting, and those like it, was also her rebellious spirit regarding societal norms showing through. Major thinkers of the day figured that the weaker sex, women, – so susceptible to hysteria – couldn’t possibly be capable of the bravura (technical skill) or creative genius necessary for them to compete with men in any circuit, never mind art. She kind of had a bone to pick with that concept.

But mostly she just really liked painting animals and I don’t think she really cared all that much what people thought about her.

Audio recording of Courbet part 1 segment:

Gustave Courbet – The First Realist

Gustave Courbet was the first real Realist. We know this because he’s the one who literally wrote the Manifesto of Realism and created the guidelines for the movement.

His story follows an unusual arc, in that he started out wealthy, handsome, and well liked but died poor and notorious. He was egotistical and cantankerous, but he had a vision for art.

Not that you would have known that he was going to be the artist to set the art-world on its ear. His early paintings sort of wander around in regards to subject matter. Wandering through ideas that are landscape based, then beauty based, then genre based. But nothing distinct seems to develop at first. But then, alongside all the scandalously raunchy nudes and suffering self portraits he was painting, he began to paint things like this:

And eventually he began saying things like this:

“I am fifty years old and I have always lived in freedom. Let me end my life as a free man. When I am dead, they must be able to say of me, ‘That one never belonged to any church, to any institution, to any academy, and above all to any regime except the regime of liberty’.” [25]

Which means we need to talk about Socialism because he is tied to that political position (not movement).

During Courbet’s time “Socialism” was a social consciousness regarding the poor. The realization that those in the lower classes lived a different experience than those in the higher classes. The idea that those who were in the lower classes didn’t have access to as much opportunity as others might have. At this point it was a realization of difference, but eventually it would grow to an understanding that something could be done by the better off to change the situation of others, and eventually it became a movement that suggested that the better off should do things for the less fortunate. However, even then “Socialism” as it was understood then, was not as it is understood now.

Socialism as a movement and more along the lines of how it might be framed today:

– Wasn’t formally invented until the 1860s, and

– Didn’t become a real political force until after WWI

In Courbet’s The Stone Breakers, he is making a real commentary on the lives of the unfortunate – the crushing existence of the lowest classes of French society. “As one begins, in this class, so one ends,” is his statement.

If we look closely at Courbet’s painting The Stonebreakers of 1849 (painted only one year after Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels wrote their influential pamphlet, The Communist Manifesto) the artist’s concern for the plight of the poor is evident. Here, two figures labor to break and remove stone from a road that is being built. In our age of powerful jackhammers and bulldozers, such work is reserved as punishment for chain-gangs.

Unlike Millet, who, in paintings like The Gleaners, was known for depicting hard-working, but somewhat idealized peasants, Courbet depicts figures who wear ripped and tattered clothing. And unlike the aerial perspective Millet used in The Gleaners to bring our eye deep into the French countryside during the harvest, the two stone breakers in Courbet’s painting are set against a low hill of the sort common in the rural French town of Ornans, where the artist had been raised and continued to spend a much of his time. The hill reaches to the top of the canvas everywhere but the upper right corner, where a tiny patch of bright blue sky appears. The effect is to isolate these laborers, and to suggest that they are physically and economically trapped. In Millet’s painting, the gleaners’ rounded backs echo one another, creating a composition that feels unified, where Courbet’s figures seem disjointed. Millet’s painting, for all its sympathy for these poor figures, could still be read as “art” by viewers at an exhibition in Paris.

Courbet wanted to show what is “real,” and so he has depicted a man that seems too old and a boy that seems still too young for such back-breaking labor. This is not meant to be heroic: it is meant to be an accurate account of the abuse and deprivation that was a common feature of mid-century French rural life. And as with so many great works of art, there is a close affiliation between the narrative and the formal choices made by the painter, meaning elements such as brushwork, composition, line, and color.

Like the stones themselves, Courbet’s brushwork is rough—more so than might be expected during the mid-nineteenth century. This suggests that the way the artist painted his canvas was in part a conscious rejection of the highly polished, refined Neoclassicist style that still dominated French art in 1848.

Perhaps most characteristic of Courbet’s style is his refusal to focus on the parts of the image that would usually receive the most attention. Traditionally, an artist would spend the most time on the hands, faces, and foregrounds. Not Courbet. If you look carefully, you will notice that he attempts to be even-handed, attending to faces and rock equally. In these ways, The Stonebreakers seems to lack the basics of art (things like a composition that selects and organizes, aerial perspective and finish) and as a result, it feels more “real.”

Excepted and adapted from: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, “Gustave Courbet, The Stonebreakers,” in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, https://smarthistory.org/courbet-the-stonebreakers/.

All Smarthistory content is available for free at www.smarthistory.org

CC: BY-NC-SA

Which isn’t to say with all of his good will toward the poor, that he stopped painting absolutely scandalous nudes and completely devoted himself to social change. On more than one occasion he created stirs with his nude paintings. One of which used the girlfriend of fellow artist and friend James Abbott MacNeil Whistler as a model. Whistler’s girlfriend, Jo, (depicted in Courbet’s Portrait of Jo (La belle Irlandaise) was Courbet’s model for a while. And Whistler was Courbet’s close friend until a particularly pornographic painting – one that was scandalous enough to cause people to file police reports once it was exhibited – was painted by Courbet while Whistler’s girlfriend was his main model. That was when Whistler, who had been very close with Courbet, suddenly went back to London to stay and never spoke to Courbet again.

Awkward.

And that wasn’t even his most scandalous piece ever. His most scandalous nude was one the public never even knew about. It was a private commission (for the same man who had commissioned Ingres’ Turkish Bath from chapter 3) that didn’t see public exhibition until the 1980s – over one hundred years after its completion!

For reasons that may never be fully explained, Courbet managed to have some influential and controversial paintings included in the Academy’s Salon of 1850-51; his Stone Breakers and Burial at Ornans were both included.

Audio recording of Burial at Ornans segment:

Burial at Ornans is one of Courbet’s most important works. It records the funeral of his grand uncle which he attended in September of 1848.[26] People who attended the funeral were the models for the painting. Previously, models had been used as actors in historical narratives, but in Burial at Ornans Courbet said he “painted the very people who had been present at the interment, all the townspeople”. The result is a realistic presentation of them, and of life in Ornans.

The vast painting—it measures 10 by 22 feet (3.0 by 6.7 meters) — drew both praise and fierce denunciations from critics and the public, in part because it upset convention by depicting a prosaic ritual on a scale which would previously have been reserved for a religious or royal subject.

According to art historian Sarah Faunce, “In Paris the Burial was judged as a work that had thrust itself into the grand tradition of history painting, like an upstart in dirty boots crashing a genteel party, and in terms of that tradition it was of course found wanting.”[27] The painting lacks the sentimental rhetoric that was expected in a genre work: Courbet’s mourners make no theatrical gestures of grief, and their faces seemed more caricatured than ennobled. The critics accused Courbet of a deliberate pursuit of ugliness.[28]

Eventually, the public grew more interested in the new Realist approach, and the lavish, decadent fantasy of Romanticism lost popularity. Courbet well understood the importance of the painting, and said of it, “The Burial at Ornans was in reality the burial of Romanticism.”

Courbet became a celebrity, and was spoken of as a genius, a “terrible socialist” and a “savage”.[29] He actively encouraged the public’s perception of him as an unschooled peasant, while his ambition, his bold pronouncements to journalists, and his insistence on depicting his own life in his art gave him a reputation for unbridled vanity.[30]

Excerpted and adapted from: Wikipedia, (October 6, 2020), s.v. “Gustave Courbet.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gustave_Courbet

One of the reasons Courbet’s Burial at Ornans was met with such derision in Paris, is because of political unrest in the country. Ornans was not in Paris, and it depicted a crowd of non-Parisian French peasants. The way voting worked in France at this time had just been changed, giving more voting sway to the provinces than they had previously had. Life outside of Paris and its districts was nothing like life in Paris and its districts and Parisians feared that those outside the city would be convinced to vote for parties that did not have the best interests at heart. (The best interests of Parisians at heart, of course.) Specifically the Parisians feared that the new voting system could give power to those who would reinstate the monarchy. Burial at Ornans reminded the people of Paris that their future was no longer completely in their own hands, but in the hands of the provincial people they declared to be ‘ugly’. (As it turned out, the Parisian fear of the voting power of the rest of the country was well-founded with the rise of Louis Napoleon and his questionable tactics to gain voters in the provinces.)

As is clear, Courbet managed to create a spectacle at every opportunity. So why should the International Art Exhibition of 1855 be an exception? It was at this Exhibition (or because of this Exhibition?) that Courbet became the name most associated with Realism. What’s the story? Well hold onto your hats!

The International Art Exhibition of 1855 was a huge undertaking and in an effort to portray France as the best in the world, the exhibition planners had things figured out. They carefully orchestrated a show with retrospectives of Delacroix, Ingres and Vernet – some of the biggest names in French art in the 1800s that far. Other artists were invited to join the show by submitting work to the jury.

Courbet, like most other Parisian artists, jumped at the chance, but he made few interesting choices. First interesting choice: he submitted fourteen paintings! No one but the deceased artists in the showcased retrospectives would have that many on display. As could have been predicted, a few of his fourteen pieces were selected but not his incredibly huge painting like The Artists’ Studio and Burial at Ornans. Second interesting choice: he decided to get huffy about the rejection of so many of his works. Pitching a Jim-Carrey-in-the-Grinch level fit at being excluded from an event he made sure he would be excluded from, he created a plan to retaliate. Third interesting choice: To retaliate and prove the deep abuses he had suffered at the hands of the jury, he built his own pavilion on the actual exhibition grounds off the Champs-Elysées next to the official exhibition. This required that he dip deeply into his personal funds and utilize favours among his friends and allies. Fourth interesting choice: he charged admission. To charge admission to an event might not seem like that big of a deal to a North American in the 21st century, but to the French in the 1800s this was almost offensive. Art had been democratized during the Revolution and art was seen as the peoples’ possession. To charge the people to see their own art was robbery! Once people paid their admission to see his exhibition of forty paintings, he presented them with copies of his Realism Manifesto and catalogue. The Realism Manifesto was the introduction to his catalogue and echoed the political manifestos of the age. In it he said:

The title of Realist was thrust upon me just as the title of Romantic was imposed upon the men of 1830. Titles have never given a true idea of things: if it were otherwise, the works would be unnecessary.

Without expanding on the greater or lesser accuracy of a name which nobody, I should hope, can really be expected to understand, I will limit myself to a few words of elucidation in order to cut short the misunderstandings.

I have studied the art of the ancients and the art of the moderns, avoiding any preconceived system and without prejudice. I no longer wanted to imitate the one than to copy the other; nor, furthermore, was it my intention to attain the trivial goal of “art for art’s sake”. No! I simply wanted to draw forth, from a complete acquaintance with tradition, the reasoned and independent consciousness of my own individuality.

To know in order to do, that was my idea. To be in a position to translate the customs, the ideas, the appearance of my time, according to my own estimation; to be not only a painter, but a man as well; in short, to create living art – this is my goal. (Gustave Courbet, 1855)[31]

Audio recording of The Artist’s Studio segment:

The result of these four choices was not an exhibition that could be called a success on any front. It was pretty much a laughing stock to the public and a complete financial failure. While it did endear Courbet to the other Avant-Garde artists and established him as an inspiration to the next generation of artists, it did prove, in some small way that an individual artist with enough spunk and guts could compete with even the grandeur of King Louis Napoleon’s seven years of reign! Which leads us one of the pieces of art he featured in his Realism Pavilion: a painting that contrasted seven years of his life (1848 to 1855) with the seven years of Louis Napoleon’s reign.

That painting was The Artist’s Studio: A Real Allegory Summing Up Seven Years of My Life as an Artist.

The title of Courbet’s painting contains a contradiction: the words “real” and “allegory” have opposing meanings. In Courbet’s earlier work, “real” could be seen as a rejection of the heroic and ideal in favor of the actual. Courbet’s “real” might also be a coarse and unpleasant truth, tied to economic injustice. The “real” might also point to shifting notions of morality.

In contrast, an “allegory” is a story or an idea expressed with symbols. Is it possible that Courbet is using his title to alert the viewer to contradictions and double meanings in the image? Look, for instance, at the dim paintings that hangs on the rear wall of his Paris studio. These large landscapes seem to form a continuous horizon line from panel to panel. They dissolve enough so that we are not sure if they are paintings, or if they are perhaps windows that frame the landscape beyond. Is it “real” or is it a representation? Courbet seems to muddy the distinction and allow for both possibilities.

The artist is immediately recognizable in the center of the canvas. His head is cocked back and his absurd beard is thrust forward at the same haughty angle seen in Bonjour Monsieur Courbet. But here he is assessing and just possibly admiring the landscape that he is in the process of painting. The central composition is a trinity of figures (four, if you count the cat).

To Courbet’s right stands a nude model. Note that her dress is strewn at her feet. There is nothing exceptional here; after all, this is an artist’s studio, and models are often nude. However, Courbet does not look in her direction, as he would if she were actually posing for him. He doesn’t need to. He is, after all, painting an unpopulated landscape. Oddly, the direction of the gaze is reversed. The model directs her attention to align with Courbet’s, not vice-versa. She gazes at the landscape he paints. In the realm of the “real,” she functions as the model, but as “allegory,” she may be truth or liberty according to the political readings of some scholars and she may be the muse of ancient Greek myth, a symbol of Courbet’s inspiration.

The boy to the left of the artist is also a reference. The smallest of the three central figures, he looks up (literally) to Courbet’s creation with admiration. The boy is unsullied by the illusions of adulthood—he sees the truth of the world—and he represented an important goal for Courbet—to un-learn the lessons of the art academy. The sophistication of urban industrial life, he believed, distanced artists from the truth of nature. Above all, Courbet sought to return to the pure, direct sight of a child. The cat, by the way, is often read as a reference to independence or liberty.

The entire, rather crowded canvas, is divided into two large groups of people. In the group on the left, we see fairly rough types described. They are a cast of stock characters: a woodsman, the village idiot, a Jew, and others. There are several other allusions, such as the inclusion of the current ruler of France, Louis-Napoléon, but let’s focus on the larger theme at hand. Here then, are the country folk whom Courbet faces.

On the opposite side of the canvas are, in contrast, a far more handsome and well-dressed party. Gathered at the right lower corner of the painting are Courbet’s wealthy private collectors and his urbane friends. At the canvas’s extreme right sits Charles Baudelaire, the influential poet who was a close friend of the painter.

Is this composition familiar? Courbet is engaged in the act of painting, or as we might say, he is creating a landscape. Could the reference be to God the creator? The composition seems directly related to the traditional composition of the New Testament story, the Last Judgment. Think of Giotto’s Last Judgment fresco on the back wall of the Arena Chapel in Padua (1305-06), or Michelanglo’s Last Judgment painted on the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel (1534-42). In those paintings, the blessed (those that were on their way to heaven) were on the right side of Christ (our left), and the damned (those on their way to Hell) were shown on Christ’s left (our right).

Courbet has placed himself in the position of creator. But does he want us to use a capital “C”? What then of the model/muse? In the place of the blessed on the left are the country folk, a reference to the morality of nature? On the right side in place of the damned are the urban sophisticates—the notion of the corruption of the city. And in the bottom right corner, where Michelangelo placed Satan himself, we find, amusingly, Courbet’s close friend, the poet Baudelaire, author of The Flowers of Evil.

Finally, note the crucified figure partly hidden behind the easel. Indeed, Courbet referred to himself as a kind of martyr (such paintings as Self-portrait as Wounded Man). He created these satirical portrayals of himself as a martyred saint perhaps because of his metaphorical “suffering” at the hands of the French art critics.

Excerpted and adapted from: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, “Gustave Courbet, The Painter’s Studio: A Real Allegory Summing Up Seven Years of My Life as an Artist,” in Smarthistory, August 9, 2015, https://smarthistory.org/courbet-the-artists-studio/.

All Smarthistory content is available for free at www.smarthistory.org

CC: BY-NC-SA

Audio recording of Daumier segment:

Honoré Daumier

Charles Baudelaire was a French philosopher. He challenged artists to paint the ordinary aspects of contemporary life and to find in them some grand and epic quality.

He said, “There are such things as modern beauty and modern heroism!”

Courbet’s big modern works were an answer to the challenge Baudelaire had put out in 1846 for large, heroic, modern life depictions but, out of all the artists he knew, loved, and supported, Baudelaire considered Honoré Daumier one of the most important figures of modern art.

Daumier made a living some of the time, especially earlier in his career as a satirical cartoonist. With biting wit and castigating charm, he frequented the pages of the newspaper Le Charivari and La Caricature with political cartoons commenting on the politics of the day. With Les Poires (French for pear, but also French slang for idiot), Daumier makes some pointed comments about King Louis-Philippe (a Bourbon King of the July Monarchy) as his portrait gradually turns into a pear. Everybody who read the caricature in the Le Charivari or La Caricature understood exactly what it meant and it wouldn’t have made the king or his supporters too happy. The director of La Caricature, Charles Philipon felt the cartoon was a success. He stated: “What I had foreseen happened. The people, seized by a mocking image, an image simple in design and very simple in form, began to imitate this image wherever they found a way to charcoal, smear, to scratch a pear. Pears soon covered all the walls of Paris and spread over all sections of the walls of France.”[32]

Apparently, Daumier had quite a bit to say about the Bourbon king Louis-Phillipe.

Daumier’s Gargantua, also published in La Caricature landed both Daumier and Philipon in prison and caused a ban on every publication in which it was printed.

Gargantua was a medieval character in French Literature, but here he’s been given the pear-shaped face of King Louis-Phillipe and has been placed on a nineteenth century toilet chair. He devours gold from the poor and expels paper documents – the inscriptions say that they are letters of nomination and appointment to special individuals and court honors. But this isn’t an illustration of taxes being used to help everyone, they were taxes being taken from the poorest and then used to fatten the already fat wallets of the rich.

After six months in prison and banning of the publication it was printed in, Daumier knew the risks associated with directly satirizing the king. He also recognized that censorship laws in France were about to get tough.

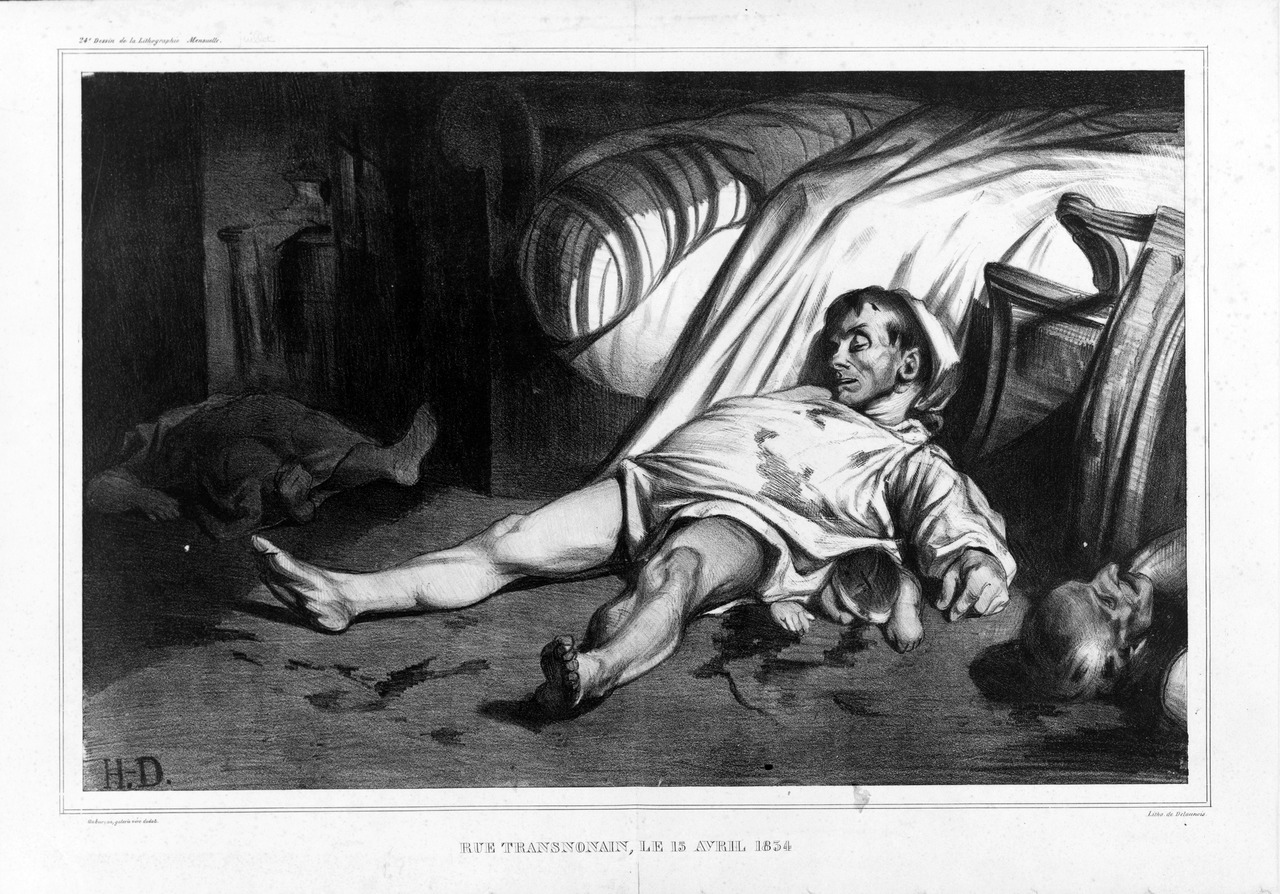

Everyone in Paris knew what had happened in the apartment building. It was on the corner of two streets—rue Transnonain and rue de Montmorency. On the night of April 13, 1834, soldiers of the civil guard entered the building going from apartment to apartment. Workers in the neighborhood had protested against the repression of a silk workers’ revolt in the city of Lyon. The soldiers then entered the apartment building in response to shots fired from the top floor during the protest. Years later, survivors recalled hearing pounding on the apartment doors as the soldiers made their way in shooting, bayonetting, and clubbing the hapless residents.

Monsieur Thierry was killed while still in his bedclothes, Monsieur Guettard and Monsieur Robichet met the same fate. A recipient of the French Legion of Honor, Monsieur Bon was killed while trying to hide under a table. They killed Monsieur Daubigny, a paralyzed man, in his bed and left his wife and child for dead. Monsieur Bréfort was killed as soon as he opened his door and Monsieur Hue and his four-year old child met the same fate. The conservative papers talked of a nest of assassins firing on soldiers, the more liberal papers offered detailed accounts of the victims.

Parisians had lived with political repression enforced by the police and civil guard for years and street battles were nothing new. The Revolution of 1830, inspiration for Delacroix’s painting Liberty Leading the People, had overthrown the repressive monarchy that followed Napoleon’s rule. The new ruler, Louis-Philippe called himself the King of the French and was supposed to be more liberal. Instead, he clamped down on public dissent and the press much like his predecessors. Those who wanted the freedoms promised by the French Revolution of 1789 attempted another rebellion in June 1832. The writer, Victor Hugo, memorialized that insurrection which left over 100 dead on the streets of central Paris, in his book Les Miserables. Somehow, what happened on rue Transnonain was different.

Today, such an event would still be covered by newspapers, but also on social media and on cell phone cameras, but in 1834 it fell to Paris’s renowned printmaker, Honoré Daumier, to show the Parisians just what had happened. But how? How do you show a massacre? And what would be the risk of publishing a print that challenged the government so directly?

Honoré Daumier came to Paris as a child when his father, a glazier and frame maker, moved his family to pursue his literary ambitions. The family was never well-off and Daumier worked from the age of twelve for booksellers and as an errand boy for a law firm to help support them. A friend of the family, the antiquarian and archeologist Alexandre Lenoir, gave young Daumier informal drawing lessons because the family could not afford any formal training for the gifted young artist.

Daumier continued to draw and study on his own, visiting the Louvre to draw sculpture and the Académie Suisse, an inexpensive studio without an instructor, where he could draw from the nude. Although he became a widely respected artist in Paris, Daumier never stepped away from his working-class origins, and perhaps this gave him the immense empathy found in his portrayal of those who perished on rue Transnonain.

The print is a lithograph—it used limestone and oil-based inks to create light and shadow similar to drawing or painting. Daumier experimented with this technique as a young teenager and later held a job working for a printmaker. By 1834, he had established himself as a caricaturist and political cartoonist, working for the publisher Charles Philipon by creating lithographs for his satirical, illustrated journals La Caricature and, after 1835, Le Charivari. Over his career, Daumier published well over 3,000 lithographs.

Among these many lithographs, Rue Transnonain stands alone for its brutal tone and unflinching commentary on what had only recently occurred. Daumier brings together a group of four bodies in one space, and extreme areas of light and darkness, to give the viewer one image that summed up the violence of that night.

Audio recording of Rue Transnonain part 2 segment:

A dead man in his bloody nightshirt, just roused out of the rumpled bed, lies prone across the composition with his body resting atop a bludgeoned child. The child’s head and chubby hands just emerge from beneath the man. Perhaps these bodies, foreshortened and moving toward the viewer, allude to Monsieur Hue and his child. To the left of the man and the child, an older man’s head enters the scene from the edge of the paper, in front of a toppled chair. These bodies, lit with a dramatic light, complement the darker portion of the composition on the other side of the sheet where a woman’s dead body moves away from the viewer into the darkness at the back of the apartment. Dark marks, likely smears of blood, litter the floor. The print is not a documentary image but one designed to evoke the brutality of the event in the starkest terms. There is no action or drama here; instead, Daumier leaves the viewer with only the stillness and silence of death.

In the years surrounding the publication of Rue Transnonain, journalists, publishers, and printmakers could face criminal charges, fines, and even imprisonment for their publications. In 1831, Daumier had created a print titled Gargantua depicting Louis-Philippe, the King of the French, as a corpulent blob with an oversized conveyor belt tongue consuming money provided by the laborers of France (Gargantua is also the name of a giant in a series of novels written in the 16th century by Rabelais). For this work, Daumier and his publisher Philipon were charged, tried, and sentenced to six months in prison. As he began work on the print, Rue Transnonain, Daumier understood the risk he was taking.

Daumier created Rue Transnonain for the print subscription, L’Association Mensuelle Lithographique and published it in August 1834. Founded by Philipon, while he was serving time in prison for the publication of Gargantua, L’Association Mensuelle distributed caricatures to subscribers on a monthly basis and the funds raised supported freedom of the press and helped to pay off Philipon’s government fines.

Rue Transnonain was the last lithograph published in that series. Although government censors had approved the print, when it was exhibited in the window of a print seller, the police took note and quickly attempted to track down as many copies as they could. The police also confiscated the lithographic stone so that no more prints could be made. The remaining original prints of Daumier’s Rue Transnonain are among the most valued of Daumier’s works. After they published Rue Transnonain, Daumier and Philipon avoided prosecution but the ultimate cost was high. The government passed a new law restricting freedom of the press and proscribed political caricature. As a result, Daumier changed his subject matter, turning his eye away from direct political critique and toward social commentary.

Excepted and Adapted from: Dr. Claire Black McCoy, “Daumier, Rue Transnonain,” in Smarthistory, October 8, 2020, https://smarthistory.org/daumier-rue-transnonain/.

All Smarthistory content is available for free at www.smarthistory.org

CC: BY-NC-SA

When the July Monarchy came to an end during the 1848 revolutions, you would think Daumier would have been ecstatic, but he quickly realize that the Louis Napoleon – elected leader of the government – was up to no good.

The Revolution of 1848 again brought a few brief years of press freedom and political caricature. To be signalized among Daumier’s work of this period is the creation of Ratapoil, the Bonapartist agent. Ratapoil is the personification of the agent-provocateur, the bully boy, a section leader of the Society of December 10, President Louis Bonaparte’s private army of adventurers and lumpen-proletariat – a seventy-year anticipation of Benito Mussolini’s first fasci. It was the Society of December 10 that Bonaparte shipped ahead when he toured France so they could impersonate the masses at each railroad station, shout, “Vive l’Empereur!“ and beat up any opponents. Daumier shows Ratapoil as a sinister, seedy, middle-aged but wiry adventurer, with an imperial beard and mustache, carrying a half-concealed club up his sleeve. This figure incarnated all of Daumier’s hate and contempt for Napoleon the Little, by whom, to his credit, he had never been taken in as had such men of the left as Proudhon and Victor Hugo.[33]

Images like Daumier’s cartoons point to how Louis Napoleon got into power in the first place – elected by the peasant majority and by manipulating the crowds.

But when Louis Napoleon declared the Second Empire, Daumier had to retreat to less direct commentary and just comment about society at large.

Daumier’s The Third Class Carriage represents early railroad travelers seated in a carriage. In this painting, Daumier did not choose to represent the wealthy bourgeois traveling in first class, but the poorer people in the third class, in order to denounce the misery that reigned in a large part of French society at that time. For the artist, it is the reflection of a reality that some preferred to hide.

This representation of reality is disturbing, not so much by what is shown, the characters, the clothes, these miserable children, as by the force of the glances. The dark eyes of the woman with the basket, in the foreground, fixing the viewer of the work, seem terribly accusing and reflect the deep disarray that inhabits these poor people, in their lives of suffering and misery. In the foreground we also have a woman with her child and a young boy. In the background we can see other people also living in suffering misery.

Excerpted and adapted from: Wikipedia, (June 28, 2019), s.v. “Le Wagon de troisième classe.” https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Le_Wagon_de_troisddi%C3%A8me_classe