2 Chapter 2 – French Revolution through to the End of Napoleon

France

Megan Bylsma

By the end of this chapter you will be able to:

- Identify art of the French Revolution by Jacques Louis David and Pierre Paul Prud’hon

- Recognize Prud’hon’s and David’s Napoleon era work and compare it to their Enlightenment era and Revolution era pieces

- List the main chronological events that took place to cause the Revolution and the important developments during the

Revolution - Recount basic high fashion changes in French court fashion from the Rococo through to the Revolution

- Explain the events that allowed Napoleon to take over the Empire

- Identify Directoire Style and Napoleon’s Empire Style

Opening of chapter in audio:

What is it that Chip says at the end of Disney’s animated Beauty and the Beast?

“Are they gonna live happily ever after, Momma?”

And we have to ask, do they?

We have to ask, because the traditional story of Beauty and the Beast is usually set somewhere in the mid to late 1700s, in Rococo France. Which, as a side note, means that Belle’s iconic, deeply shoulder-less, canary yellow ball gown in the animated feature just might be a bit anachronistic considering how fashionable wide side cage panniers on skirts were and how impossible it was to create such bright and clear yellow fabric in that era. Side panniers were cages worn under the clothing and attached to the body of the woman on a belt at the waist and were used to create a wider-than-she-is-flat silhouette. Bright, clear colour only became possible with the invention of synthetic fabric dyes later in the 1800 and even 1900s. This painting of Princess Louise Marie by François-Hubert Drouais may be a closer approximation of what Belle’s dress would have looked like, complete with side panniers. The setting of Princess Louise Marie’s portrait is fitting of Belle though – it’s a library. Belle’s animated dress departs from fashion norms of its time in many ways, but one of the most startling, beyond the bell-shaped silhouette more fitting of styles to come one hundred years later in Victorian England, is the neckline. Plunging necklines, like the one on Princes Louise Marie’s dress, were very common, but combining a low front with a very off the shoulder neckline and a barely there slip of sleeve would have been bordering on unacceptably scandalous in Rococo France. While the lowest of fronts was only for the most adventurous dresser, and a smidge of shoulder showing was quite flirtatious, to show the full shoulder and arm would have been beyond acceptable standards for even the most rule-flouting of women. Even though Rococo fashion was adaptable to an individual’s personal tastes in many ways, the majority of dresses had a just-past-the-elbow sleeve and the upper arm was rarely bared. While Belle wears long gloves in the animated feature to counteract the amount of skin shown by her bare shoulders and arms, gloves were not common (although they did make an occasional appearance) in Rococo France and wouldn’t have distracted from her alarmingly unclothed appearance. With this in mind, if you’re wondering, after looking at Princess Louise Marie’s dress, how a woman’s, ahem, chest stayed in her clothing when the bodice was cut so low and was only bordered by lace, well the answer is that it usually didn’t. French fashion of the period was greatly varied, but extremely low-cut bodices were frequent and the accidental (but inevitable) wardrobe malfunction was often simply part of the price of high fashion and was not considered as utterly reputation ruining as a fully bare arm and shoulder.

But returning to Chip’s question regarding Belle’s future happiness; approximately five to twenty years after the close of the movie, some things in France begin to change. Changes began to creep in, even in a provincial town that used to be “a quiet village, every day, like the one before.”[1] While Belle’s ideologies and values align fairly well with the beliefs of the philosopher’s of the Enlightenment and she would have definitely supported them, she had the misfortune of marrying into the aristocracy. In the events that followed that last happy closing scene of Beauty and the Beast, being part of the aristocracy was bad for ones health. Perhaps even worse? Chip himself would have grown up and either have been called up or joined voluntarily to fight as a soldier or he would have been exiled back to England, as he and his mother were obviously British.

What is the event that would have so disrupted the lives of Belle and her prince?

The French Revolution

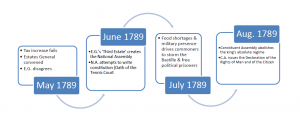

The French Revolution is a complicated series of events and it can be easy to become bogged down in the details of what happened first and then what happened next while not forgetting what came in the between time. For art history the French Revolution is a dramatic and devastating series of events. Essentially, it ran from 1789 to 1795 although some say it went right up to 1815, while others say it went to 1799. The date range of the Revolution depends on where you decide the Revolution ends, as everyone agrees on the date that it started. Some sources will say it ended with Napoleon’s first exile, for others it ended with the rise of the Bourbon Monarchy, others posit it ended with the final exile of Napoleon and the final democracy. Art history tends to label the end of the Revolution with the rise of Napoleon as he ushered in his own changes to the art and culture of France. This isn’t to say that French politics were completely stabilized by the rise of an emperor, but rather that the revolutionary aspect of the period gave way to a new approach and the art and material culture of the time reflects that.

The French Revolution irrevocably changed the face of French culture. As an agent of cultural change, the Revolution tends to often be talked about in bright and celebratory terms. However, to uncritically celebrate the French Revolution means to ignore the incredible violence and loss of life the Revolution brought to France.

In some ways the French Revolution brought about some good things. Slavery, long abolished in main-land France, was, in 1794, declared illegal in the French colonies.[2] In 1791 the new radical government opened the Salon to all artists, including women, regardless of political affiliation.[3] The Revolution also gave birth to the public art museum, in 1793, when revolutionary forces sought to democratize access to art and the cultural power it holds by removing the monarchy from the Louvre and opening the government’s art holdings to the public.[4]

Regardless of the good changes wrought by the French Revolution and the good intentions of the revolutionaries in the early days of the upheavals, things very quickly turned into brutal violence, deaths, and fighting between factions in the revolutionary forces.

Next section in audio:

Unrest in France was long growing, but things were brought to a point by the end of the American Revolution. The French had watched the American Revolution with interest, wondering if it was possible for the ideas of the Enlightenment to create the spark necessary to dislodge the weight of a ruling power. When the colonists defeated their British rulers, the French found encouragement that perhaps they too could shrug off the weight of their rulers, at least in part. What began as bureaucratic changes related to budgetary concerns earlier in 1789, then became full on rebellion against the monarchy when the Estates General (an assembly representing all three levels of society – the First Estate representing the clergy, the Second Estate representing the nobility, and the Third Estate representing the common class), led by the Third Estate, due to their large size, declared themselves a National Assembly. Later in the same month, the National Assembly wrote the first of many constitutions that created a new government with the monarchy as a figurehead, instead of an absolute ruler.

Jacques-Louis David’s Oath of the Tennis Court represents the moment, on June 20, 1789 that the National Assembly found themselves locked out of the chambers they had been using, and they subsequently gathered at a nearby tennis court fearing that they would be attacked by the king’s troops. Once gathered, they collectively swore to not leave the place until they had established a constitution. David’s drawing shows all three Estates – the clergy, the nobility, and the common class – agreeing together in the middle of this image. Within the same year the abolition of feudalism and the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen would be written. The oath of the tennis court was an important moment as it was the first time the French people had significantly stood in opposition of the king.

However, as the monarchy resisted change the king ordered the military to move into the city of Paris. The king wanted the military close in the event that there was a political uprising (more than what had already happened in the previous month) but the city of Paris was in the middle of food shortages due to an agricultural crisis gripping the nation. As soldiers and Parisians began to aggravate each other unrest grew until July 14, 1789. On that day the people of Paris stormed the Bastille – the medieval fortress that housed political prisoners and an arsenal for the military. While the Bastille was not an important or much used prison, it was seen as a symbol of the absolute authority of the monarchy and the wasteful spending habits of the government. The storming of the Bastille is usually seen as the moment that the violence of the Revolution began.

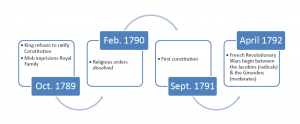

Not surprisingly the king refused to ratify the constitution that removed him from authority and in the same month an angry mob descended on the palace and imprisoned the Royal Family. By February of the next year the Catholic Church was told to remove all of its personnel from French soil and forfeit their land and assets in France to the new revolutionary government or risk the death of their clergy. Later the revolutionary government passed their first constitution, but it was a hotly debated topic and over the course of the winter relations sour between the factions in the revolutionary groups and the Revolutionary Wars begin in the Spring of 1792. The three major factions of the revolutionary forces by this time were the Jacobins, the Montagnards (or the Mountain), and the Girondins. Of the three sects, the Girondins were the most moderate and the Montagnards the most radical. In a general sense, the Montagnards agreed more often with the Jacobins – who were also quite radical, and least often with the the Girondins – who were considered moderate (for revolutionaries). However, not all Jacobins agreed with the Mountain’s approach to things and not all Jacobins were Montagnards (although many Montagnards had at one point politically identified as Jacobins). While this may sound like a Dr. Seuss riddle from our nightmares, understanding the surface of this political landscape is necessary to be able to read the art that comes from this time period, especially the pieces created by a Jacobin-Montagnard artist we’ve touched on before – Jacques-Louis David.

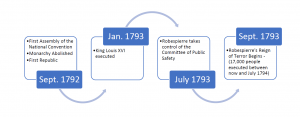

As the year 1792 turned int 1793, the Girondins began to lose their footing in the revolutionary government and were out voted in the matter of what to do with the royal family. The Montagnard call for the execution of the king came to pass at the beginning of 1793 and by the summer of that year Maximilien Robespierre, now a firm leader of the Montagnards, took control of what was essentially the functioning government of France by this point – the Committee of Public Safety. By Fall of 1793 Robespierre and government started to resort to terror, harsh sentences, and frequent executions to squelch any dissent. Death was the sentence for anyone of a different opinion to the Committee of Public Safety, anyone of suspiciously aristocratic birth, or for failing to lead a military win in a battle those not on the front thought should have been win-able. The Reign of Terror would swallow up 17,000 souls on the guillotine, including that of the former Queen of France, Marie Antoinette.

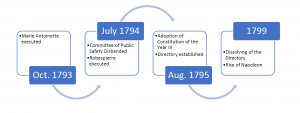

With the people sick of the bloodshed and tired of living in fear of a new and violent tyrant, Robespierre was arrested and convicted, and executed on the guillotine he had sentenced so many to die on. In the aftermath of the Reign of Terror a new constitution is adopted and a new governing body, called the Directory, was established. After years of little stability and an abundance of weak governing, the Directory in turn, was dissolved (because it was unable to do its job due to petty arguments, in-fighting, and disagreements within its own ranks). Seeing the weakness of the Directory as an opportunity, Napoleon returned from military campaigns in Egypt and rose to power. With the rise of Napoleon, France entered a new era no less tumultuous and interesting – the era of France as an Empire.

Next section in audio:

Jacques-Louis David – Revolutionary Artist

Jacques-Louis David was a well established artist in France by the beginning of the Revolution. He was a popular and respected Neo-Classicist and his art was felt to show the important aspects of the Enlightenment. In his personal life David was a highly politically active figure and his values aligned with those who called for the absolute destruction of the nobility, the monarchy, and the king. He was part of the council that had direct vote over what happened to the king and his family, including the decision to behead the king. He was a member of the Committee for Public Instruction (Propaganda) and eventually became head of the Interrogation Division. Interrogation (a term used loosely to describe interviewing people while sometimes subjecting them to pain) was used for those who either had information or were thought to have information and had been brought up on charges against the government. A Jacobin and Montagnard, Jacques-Louis David had friends in high places and influence far beyond the reaches of the art world.

Jean-Paul Marat was a personal friend of David and a rabid writer for the Montagnards. Before the Revolution Marat was a theorist, philosopher, and scientist but once the Revolution took hold of France he became more active as a politician and journalist. However, by the time the Reign of Terror began Marat had begun to be less active in the government due, in part, to his skin condition and also in part due to the fact that his vehement support of the Montagnards was not as necessary to their political aspirations after the removal of the Girondins from the government. Working from home in a medicinal bath for his worsening skin, Marat’s lessening influence in the government did not lessen his writing volume.

Jacques-Louis David, while rising in the new government, maintained his friendship with Marat; in fact, he had visited Marat the day before Marat’s death. In the painting, Death of Marat, David created a tribute to his friend that doubled as an artistic propaganda piece for the Montagnards. Marat is depicted in a pose familiar to the Roman Catholic-raised French and the meaning of that pose would not have been lost on French viewers. The scene? The Pietà. A uniquely Catholic scene, it showed the twisted and peaceful body of the crucified Christ as depicted after being removed from the cross; whose peaceful face, shows that Christ had accepted death as a necessary element for the salvation of others and therefore did not fight or resist that death. David had also place Marat in a deep contemplative space surrounded only by the darkness of the space and bathed in the warm light of noble sacrifice. The writing on Marat’s box-desk at the bottom of the painting means ‘To Marat – David’ and with this tribute to the Montagnard’s death David elevated Marat to the position of a secular martyr for the revolutionary cause.

Charlotte Corday was a Girondin whose family blamed Marat for the September Massacre. She convinced Marat to meet with her with the letter depicted in Marat’s hand, that said according to David (roughly) “I am unhappy and therefore have a right to your help.” She claimed to have information regarding a conspiracy and was offering that information to Marat along with the names of important Girondins. However, her true motive was she had planned to kill him. Eager to hear her information, Marat invited her into his room where he was soaking. After some conversation, Corday stabbed Marat once in the chest with a knife she had hidden in her dress. Once she had done what she had come to do, she did not flee the scene of the murder, but waited to be arrested. Within four days she was tried and executed. Corday had murdered Marat in hope of weakening the Montagnards and bringing an end to the Reign of Terror but the death of Marat became a pivotal propaganda and rallying point for the group as they gained momentum.

However, times change and when the threat of terror and death is no longer there people’s opinions sway. Someone considered a champion and non-religious martry for a cause after a time can be seen as a beast and problem-causer. Consider this painting of the same event by Paul-Jacques-Aimé Baudry. Painted in the mid-1800s, by this time Marat was seen as a blood-thirsty monster whose writing incited violence. Titled Charlotte Corday, it focuses on Corday, and reduces Marat to a monstrous figure who, in the end, fell short of the stoic ideals of the Enlightenment. In Beaudry’s painting Marat’s figure is twisted, not into a peaceful Pietà scene reminiscent of sculptures of the death of Christ, like David’s piece, but instead twisted as one who fought death and resisted it. He did not peacefully and nobly accept his fate and calling, but tried to get away, knocking his writing table into his bath and the chair over in his futile attempt. In Baudry’s painting the knife remains in Marat’s chest as evidence of his violent death. In David’s it has slipped quietly to the floor, more an artifact of a great man’s passing than an implement of death. Here Marat’s face has formed a mask of fear and pain; in David’s it is quiet and glows with divine light. In David’s painting, Marat’s apartment has been transformed into a dark and contemplative space but Baudry depicts Marat’s apartment much like it probably would have been – a lived in space with the accoutrements of a life lived within its walls.

In David’s painting the role of Charlotte Corday has been completely ignored. Her existence has been erased except for the consequences of her actions. The subject of David’s story is Marat and the cause both he and David had fought so hard for. In Baudry’s painting the focus and hero is Corday herself. Here it is the killer, not the killed, that exhibits the calm and noble sense of spirit. Her face relays resolve as she waits to be arrested, while her hands twist in turmoil over the violence of her act and the judgement she knows will come. She is a representation of duty; she is one who has done what they knew had to be done and who is willing to deal with the consequences of those actions. In the course of just over sixty-five years the story of Marat had shifted to being the story of Corday, a hero of her cause.

Next section in audio:

Traditionally, art history texts don’t mention Baudry’s painting or Charlotte Corday, instead they spend the time heroizing Jacques-Louis David, Jean-Paul Marat, and the French Revolution as a whole. Jacques-Louis David was a gifted artist and his ability to take a scene and elevate it to quietly sublime propaganda is not to be undermined. However, does the beautiful and skilful production of objects alleviate a historical figure from their role in violence and harm? As an artist, David is unparalleled during his time. As a human-being, David may leave a lot to be desired. David’s reputation as a skilled artist has largely overshadowed his involvement in the more bloody parts of the French Revolution and history has been remarkably kind to David’s memory and his artistic endeavours before, during, and after the Revolution. However, not everyone has the privilege of having their shortcomings forgotten in the light of their accomplishments…

Marie Antoinette

If you are asked to think about Marie Antoinette, what would come to mind?

A sexy Marie Antoinette Halloween costume? Images of cake? Scandalous liaisons, infidelity, and lavish parties? Powdered wigs and French debt? A bored and spoiled princess out of touch with life beyond her palace walls?

In the 2004 film Mean Girls the titular girls of the movie have a book in which they write down rumours and facts about the people they dislike. They call it the “Burn Book” and it contains all the socially questionable decisions, snipe, and gossip of an entire microcosm as seen through the eyes of North Shore High School’s most powerful queen bees. It could be hoped that the concept of writing down inflammatory things and creating reputations for people that simply were not true or were just one representation of a single event is something that only shows up in the fiction-based entertainment of the early 2000s, but that would be wishful thinking.

For most of us, Marie Antoinette lives in our popular collective understanding as caricature of grotesque and taboo traits, rather than as a human being that existed in the same world in which we live. Much of what we popularly believe we know is based on rumours that were never true but were perpetuated by a 1700s version of a burn book – actual books and cheap sensationalized newspapers (what we would call tabloids today). Marie Antoinette, like Jacques-Louis David, was a multi-dimensional and complicated human being. Her story is one that has been told and retold, but much of what is told about her is a repeating of her flaws (unlike the kindness history has shown David’s flaws) and the retelling of the lies that were spread during her life. Her life was the result of a cataclysmic combination of bigotry, rules of tradition, narrow-mindedness, and spiteful back biting.

At 12 years old, Marie Antoinette was a princess in the court of the Austrian royal family. She had been born and raised in Austria and as she entered adulthood she was the only female left in her family eligible to be married to the French male monarch. Her sisters had either been handicapped by smallpox or had died from it in their childhoods. However, there was a problem with her that the French could not ignore.

Her teeth were not nice enough according to French court customs.

This could be fixed, the French said, if her family was willing to have her undergo oral surgery. The Austrian royal family consented and young Marie (then named Maria Antonia) had her mouth changed to fit French aesthetic customs over the course of three months without anaesthetic or antibiotics. When she was considered to have a nice enough mouth, she was betrothed to her second cousin, a person she had never met – the teen-aged Louis Auguste future king of France who had been trained since birth to never trust an Austrian.

When she was thirteen or fourteen this portrait was made of her, to be sent to Louis Auguste so he would know what his future bride looked like. At fifteen she was married-by-proxy to the future king of France. Marriage-by-proxy means that the ceremony was performed without the groom present except by a proxy who could legally give the prince’s consent to the marriage. She travelled to France, where she was relieved of all her belongings, her name was changed from Maria Antonia to Marie Antoinette, and she entered a royal court that was far more formal than her own and deeply suspicious of anyone from Austria.

Over the course of the next four years, Marie Antoinette’s life was much different than she had experienced in Austria. She had been raised quite simply (for a monarch’s child) in Austria. Austrian royal children were encouraged to play with commoners and were not forced to live by the strict rules and rites that the French monarchy had instituted as a tradition for its own children. Now in France and grappling the with the rules and traditions of the French court, her new life was plagued with problems ranging from political issues (with intense scrutiny from her French peers if she involved herself in political life while also receiving disparaging letters from her mother for not being influential enough in political things), to her husband’s lack of interest in her as a wife, as well as interpersonal clashes with people such as her father-in-law’s mistress.

At age nineteen, Marie Antoinette’s father-in-law, King Louis XV of France died. Louis Auguste was crowned king and became King Louis XIV and Marie Antoinette was made the queen of France. With the king’s approval Marie Antoinette began to make changes to court life. The queen of France had responsibilities in the court and these frequently revolved around fashion and court rituals. Inspired by her own simpler upbringing, as queen she began to strip away away some of the more antiquated court rules & to tone down the excessiveness of court fashion. It was part of her job as queen to spend lots of money on her looks (she was expected to always look better than the rest of court, even while the court emulated her in every way) and to host lavish and expensive parties. Her unhappiness coupled with the king’s indecisiveness regarding the handling the nation’s finances, made it easy to spend money in her role as queen. Marie Antoinette’s spending habits would later be used against her.

Next section in audio:

As she continued to make changes in the French court fashions she eventually added ‘mother’ to her job title. With that change she made it clear she also meant to raise her own children. This was scandalous as child rearing was not an appropriate activity for French queens. However, the birth of her first child also created more issues in her life as she was already suffering from an un-diagnosed malady of the uterus (possibly cancer or some other disease) and the childbirth nearly killed her. During her convalescence, her hair fell out and her hairdresser was forced to cut her hair and make wigs until it grew back. When it grew back it came in sparsely and was no longer suitable for court hair fashion but this gave her the chance to also tone down another facet of the court. She, by necessity, moved from the large ‘pouf’ hairstyle seen in Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun’s portrait of 1778-79 – a style that could add up to three feet to the stature of the wearer and could weight in the range of 20lbs depending on how much wire caging and jewelled elements were added – to the coiffure à l’enfant (literally ‘baby hairstyle’) seen in Vigée-Lebrun’s portrait of her from 1783.

Also, notice the dress in the 1783 painting. The huge shift in fashion depicted in this painting made this a big controversy picture in its day. Viewers petitioned for it to be removed from the Salon show it was in and considered it a completely inappropriate representation of a queen. Marie Antoinette had slowly gotten rid of the big panniers and whale-bone trussing for dresses and had implemented a smooth, simple design. Part of this was possible because of the Rococo fascination with shepherdesses and simple purity and this was partly her Austrian upbringing coming out (not that Austrian royalty had simple fashion as a commoner might view but, it was much simpler than the French customs). So a straw hat, low hair and a ‘simple’ dress made of cotton were scandalous in an era when everything but nothing was scandalous.

This dress and Marie Antoinette’s massive influence changed French fashion forever, but she may have inadvertently changed the entire world with this dress. Some believe that this dress, made of cotton, catapulted the cotton industry into the stratosphere, and through a butterfly effect impacted the entrenchment of slavery in the very recently revolutionized United States of America. For more reading regarding the impact of Marie Antoinette’s cotton dress see Carol London’s 2018 article at Racked.com: https://www.racked.com/2018/1/10/16854076/marie-antoinette-dress-slave-trade-chemise-a-la-reine

Before we move completely away from French fashion to discuss the reverberations of the French Revolution in the life of Marie Antoinette, there is a pressing question that must be answered.

What colour was Marie Antoinette’s hair?

Each image of Marie Antoinette in this section gives a different answer. In the 21st century, in an age with photo filters and faded historical photographs, it is easy to dismiss the changes in hair colour and unconsciously assign her hair a colour. Brown or grey would be the logical choice.

But at fourteen years old, would Marie Antoinette naturally have such white hair?

Seems unlikely.

In the 1700s, hair was fashionably style with a combination of hair product (a kind of waxy pomade) and powder. The powder stuck to the hair product and these worked double duty – on one front it kept the hair style in place and on the other it allowed for the hair to be coloured if the powder had been mixed with pigment. It was not uncommon in the French court of this time for women to sport pink, purple, grey, or brown hair due to the colour of their hair powder. Marie Antoinette has portraits of her with each of those colours. Obviously, white or grey was the easiest hair colour as that was the colour an untinted powder would produce. However, Marie Antoinette favoured purple throughout her wardrobe and purple hair also graced her ensembles from time to time.

But what was her natural hair colour?

Unfortunately, it was a strawberry blonde. Each hair colour had a purpose in the world of French fashion, except for one.

Red hair.

Historically red hair was the colour of hair for actresses and prostitutes. For a French queen to have red-toned hair? Scandalous!

On days that Marie Antoinette was feeling particularly rebellious, she would leave her hair unpowdered and in its natural colour simply to scandalize the court. As time progressed it became apparent that no matter what she did, it would always be a source of consternation and offence to her French peers.

Eventually, as the revolution began to heat up, Marie Antoinette was the target of many other scandals. In the daily tabloids she was accused of treason, lesbianism, incest, orgies, funnelling money to Austria, plotting, and many other crimes and misconducts. When the royal treasury went bankrupt due to mismanagement and indecision by the king (and no cutting of expenditures in the palace) she was called ‘Madame Deficit’, as if the queen herself had bankrupt the entire nation.

Soon she realized that there was nothing she could do about her reputation – if she had a baby it was because she had an affair (in fact, the paternity of all her children was questioned at one time or another) – if she got a visit from family in Austria it was because she was stealing money – if she took part in politics she was running the country – if she didn’t take part in politics she wasn’t doing her duty. When she bought a property to leave to her children who wouldn’t inherit the throne (her younger children) she scandalized the nation – queen’s didn’t own things, kings owned things. So then she tried to re-brand herself as a good mother. This went against her too though, as in France queens did not raise their children – it was considered bad taste and the custom was that the state raised royal children. The campaign to show people she was a good mother was suddenly dropped when she went into mourning at the sudden death of her youngest daughter. Around the time of the Oath of the Tennis Court, her oldest son died of tuberculosis. She was devastated and in mourning while the daily tabloids ran rumours that Marie Antoinette was wishing to bathe in the blood of the people. It was clear no one cared that the crowned prince of France had died and later she would be accused of having raped her son to hurry his death.

Next section in audio:

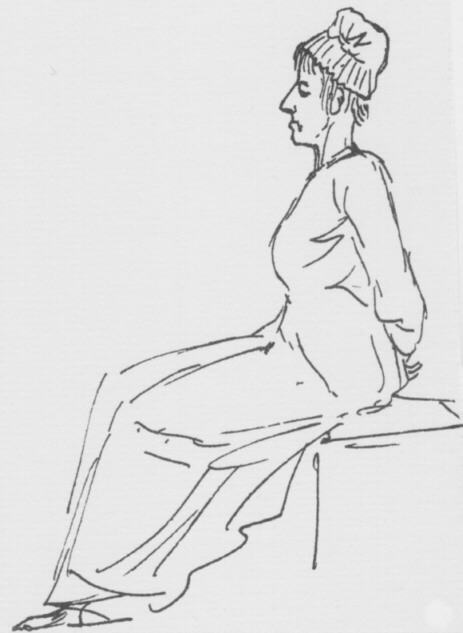

In this pen and ink sketch, Marie Antoinette is depicted by Jacques-Louis David as a hag. During the events of the first few years of the French Revolution she had aged considerably. Separated from her two remaining children, she was accused of many things with the one charge she found most offensive being the charge that she had engaged in incestuous relationships with her oldest, now dead, son in an effort to kill him in his weakened stated of advanced tuberculosis. At her trial, she was accused by her youngest son (who had been removed from her care and placed in the charge of a cobbler for a ‘untainted’ and retraining upbringing as a commoner and had been coached in his story by the Committees of Investigation and Safety led by David and Robespierre) of incest.

Before her trial she suffered many things She was stripped of her name (again) and was renamed the Widow Capet. Her husband was executed. Her best friend was raped, humiliated, decapitated, quartered and her body parts paraded in the streets. Her hair turned white nearly overnight and had then fallen out (again). Her husband’s sister, and closest family member, was also imprisoned awaiting execution. She suffered from terrible stomach cramps (due to that un-diagnosed illness) that progressively got worse during her imprisonment. Her daughter was sent to Austria as a prisoner. And finally, the former queen of France was trundled around the city on display in an open cart like a prize veal and then executed via the guillotine. After her death, her son was put in prison and left there to die.

Her last recorded words were to her executioner, “I beg your pardon, sir. I didn’t mean to.”

While climbing the stairs in the purple shoes that had carried her from the palace at the beginning of the Revolution to the executioner’s square at the end of her life she had accidentally stepped on his foot.

Even in her last words, Marie Antoinette’s character was questioned. Had she apologized because she truly was a genteel woman who naturally apologized when she tread on someone’s foot or had she meant to manipulate the executioner into ensuring that the guillotine was successful on its first pass, thus saving her from a long and painful death?

Pierre-Paul Prud’hon and Other Post-Revolutionary Developments

Despite the fame of Jacques-Louis David, there were other artists in France at the time. Younger than David but just as gifted at creating art of the Revolution was an artist named Pierre-Paul Prud’hon. Prud’hon had been trained outside of Paris. He was an amazing portraitist and this skill stood him in good stead as portraits were always in demand and were a good source of income during a time when there were few patrons for more expensive types of art. Art sales of all kinds had declined as the Revolution raged on as poverty grew, but portraits were a cheaper form of art and were popular as family mementos. Prud’hon’s work was largely overlooked for a time as a strong ability to master chiaroscuro was undervalued until the rise of Romanticism in the 1800s. The Neo-Classical tradition of the late 1700s valued strong contour lines but Prud’hon’s art focused on rendering the shifting values of light and dark across the figure. However, he was still a sought after artist in his time.

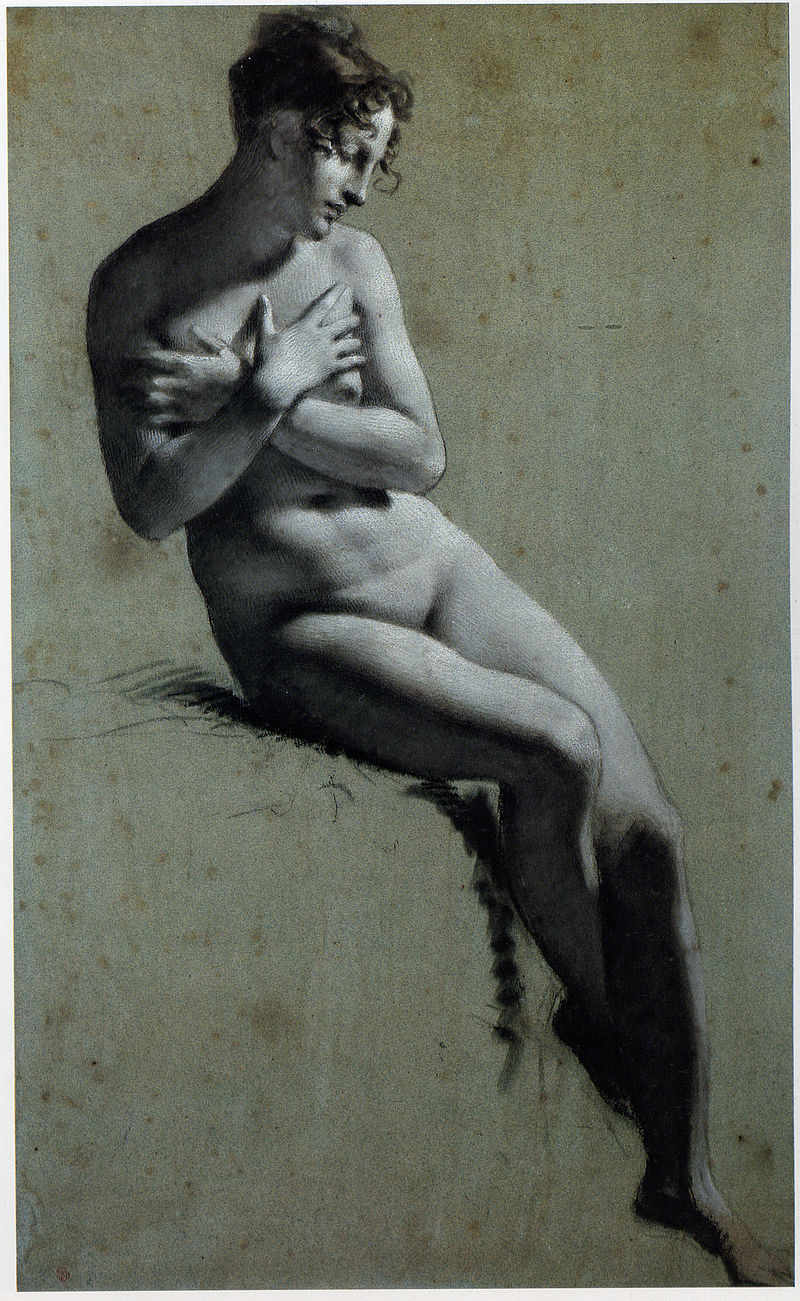

In Prud’hon’s chalk and charcoal drawing of a female nude it is clear to see how he blends the rules of Neo-Classicism with his own approach to rendering soft values. The contour lines of the elbows, knees, and nose are strong against the background while the soft tonal shifts of the abdomen lend a three-dimensional rendering to this image. By deepening the dark values of the thigh and lower leg of his model he allowed the lighter areas of the piece to emerge more strongly, giving a real suggestion of light, shadow, and reflected light. Neo-Classicism tended towards a flatter style that utilized contour line more strongly, but in this piece it is clear that Prud’hon, trained in the Neo-Classical style, had intentions to take it beyond its boundaries.

Robespierre came to power in 1793 and for eleven months terror reigned down in Paris. 17,000 people were executed, including the King and Queen. Eventually Robespierre’s cruel reign came to an end and he and his supporters were removed from power, with Robespierre being arrested, tried, and executed.

Alexandre de Beauharnais – the first husband of a woman named Josephine – was tried and executed five days before Robespierre’s execution. de Beauharnais was arrested for being suspiciously aristocratic and not leading the troops to victory during a battle. (Yes, actually. Those not involved in the battle felt if he had really wanted to, he could have managed to win. But because he didn’t win, that was seen as evidence that he was a traitor.) His wife, Josephine, usually called Rose, was also arrested but was eventually released. This Josephine would later become the wife of a 26 year old Napoleon Bonaparte – an political figure and officer at that time.

The Directory was established in 1795. It was a body of five Directors who were executives of the French government. The governing bodies of France were somewhat democratic during the Directory, but failed within four years due to civic discontent, lack of co-operation between political parties, extended wars-for-gain, and financial ruin. The Directory had promised to uphold the Constitution III but the Constitution hadn’t been written with money and corrupt officials in mind. The impact on the arts of this short period was the creation of Directoire Style. Directoire Style was neoclassical fashion and interior design and its development was mostly limited to just those two areas. The other Fine Arts largely maintained their Neo-classical-all-the-time aesthetic.

Jacques-Louis David had been thrown in prison following the arrest of Robespierre and had managed to be released without being executed after a few years. But the France he was released into was not the France of the Revolution he had left. No longer on the wealthier side of the Revolution he painted The Intervention of the Sabine Women, a painting he had started planning out while in prison, and he charged admission for people to see it. This was a scandalously undemocratic handling of art and there was much talk about paying to see art – art was for the people. However, this piece wasn’t created for a patron as most pieces were and David needed money, so he devised the plan to charge admission to recoup his costs. At this point in time the Academy had been defunct for years so their rules regarding free-admission and democratic access to art no longer applied.The painting also brought David to the attention of Napoleon.

Next section in audio:

The battle depicted is a battle between the Romans (right) and the Sabines (left). The woman in the middle with arms outspread is Hersilia. She was the daughter of the Sabine Tatius (left) but she was also the wife of the Roman Romulus (right). She is depicted begging for peace – she had been kidnapped from Sabine three years earlier by the Romans who needed women. Eventually the Sabines had come to avenge their women’s kidnappings, but at this point revenge would only hurt the innocents who were related to both – the children.

At this point in the Revolution in France the political parties were so at war with each other this painting was seen as a cry for a peace worth fighting for.

Let’s talk about Napoleon!

Was he a tall man?Napoleon had been an officer and lieutenant in the Army but returned to France to stage a coup when he heard how the Directory was behaving and saw their weakness as a political opportunity. Napoleon is often described as incredibly short. In fact, there are theoretical complexes and stereotypes that are named after Napoleon that revolve around people who are short and the psychological impact that may have on them (these theories are largely debated and disputed. Much like Napoleon’s actual height.) Often, Napoleon is listed as being 5’2”. However, those were probably French measurements which were slightly larger than British measurements. When his French height and history was translated into English and into British measurement, the British kind of just left them untranslated and then ran a lot of cartoon propaganda that advertised him as rather short.

Napoleon hated being depicted as short, which gave British cartoonists a very easy joke to make.[5] In the time of unrest between the French and British after 1803, Napoleon was frequently featured in satirical cartoons as being a short and angry man, and in the two hundred years that have followed that ‘joke’ has been repeated as fact.[6] In reality, it is likely that he was actually around 5’6” or 5’7″, which would have been slightly above average height for men of the time. In some French paintings he may have appeared short because he was often depicted with an elite squad of soldiers who were all known for being extremely tall for their day. The French and the British have a long history of fighting between themselves and it looks like that while Napoleon and the French may have tried their best to route the British, historically the Brits got the last laugh on Napoleon (albeit in a bit of a petty victory)!

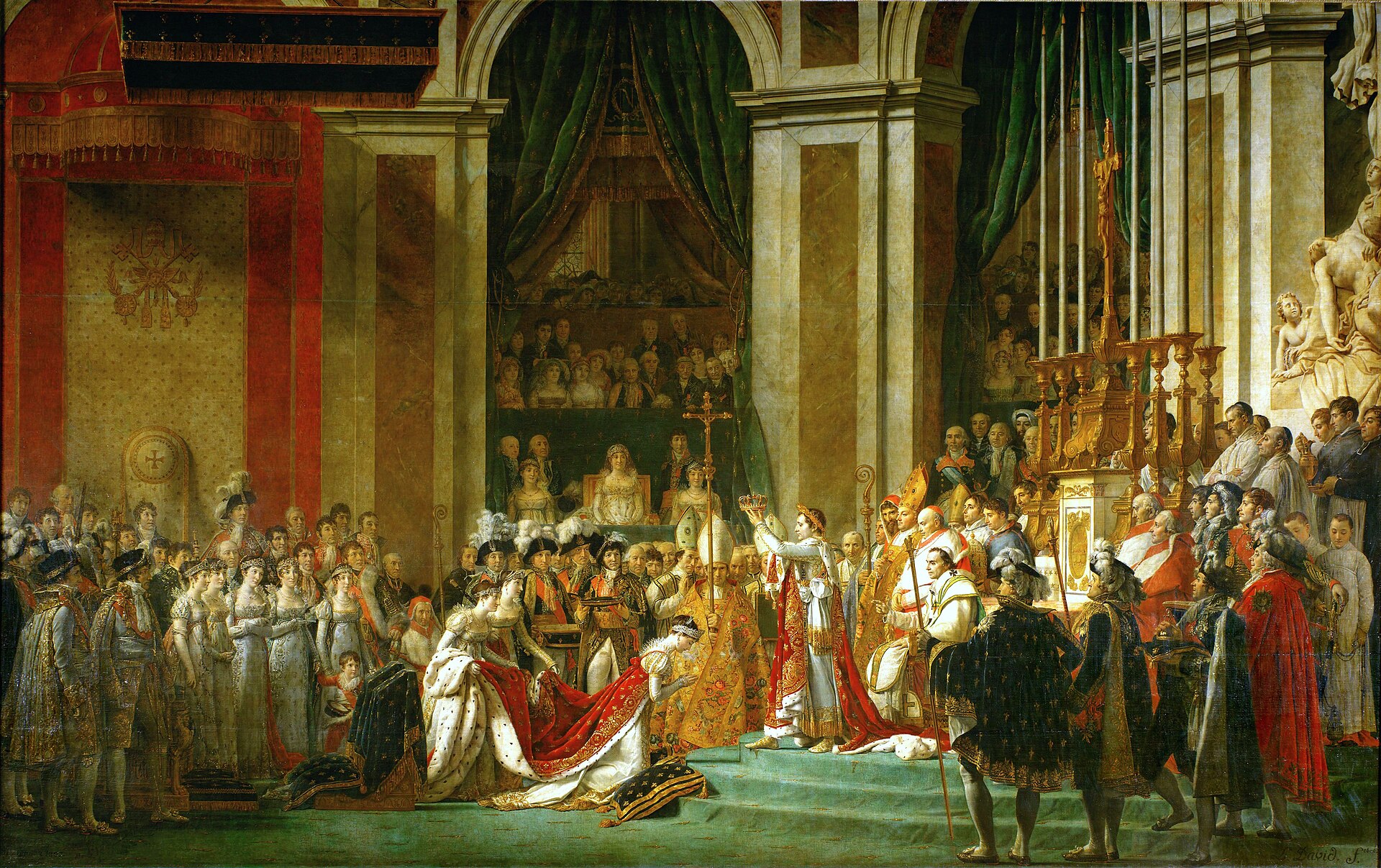

After Napoleon’s successful coup of the Directory, he took control of France in 1799. When the Empire was proclaimed in 1804, Jacques-Louis David was given the official role of court painter. In the process of painting the scene of the crowning of the Emperor Napoleon and Josephine, David was even visited by the Pope! (Which is interesting for a revolutionary who was part of the group who demanded the secularization of a nation.)

Napoleon became Emperor in 1804 – crowning himself and then crowning Josephine. The Pope was present for this proceeding and had originally been the one who was to crown Napoleon (before Napoleon took the crown and crowned himself instead) which is also very interesting considering how anti-religion the Revolution had tried to be. Napoleon, who was eager to not be from a line of monarchy used emblems from monarchy tombs that linked him to the reign of Charlemagne, the favourite king of the papacy and the Merovingians, the earliest rulers of the geographical area known as France (then Gaul). To understand just how politically crafty this maneuver was let’s talk about the French history of bees.

The Merovingians were considered the first kings of France and ruled from around 400 C.E. Three hundred of these gold and garnet bees depicted on the right had been found during the mid 1600s in the tomb of Childeric I along with other artifacts. (Most of which was stolen in the 1830s and only these two bees here and few other pieces were ever found – at the bottom of the river in the 1800s.) To the Merovingians the bee was sacred and divine and a symbol of their power.

Interestingly, there was an argument that the symbol of the Merovingian Bee evolved into the fleur de lys. This theory was disputed and discredited by historians in the 1800s after Napoleon’s reign because this argument would have given credence to the Bourbon Monarchy’s claim of a Merovingian blood-line right to the throne. Also, the fleur de lys, as its name suggests, was popularly believed to represent a lily or more precisely an iris. Alternatively, the fleur de lys could also have come from the shape of the ‘sting’ of the early Frank dynasty (aka Merovingian). A sting was a kind of spear. Some argue that Napoleon didn’t claim the bee as his personal symbol because of the Merovingian Dynasty but because he refused to spend the money to redecorate the palace. He couldn’t leave the fleur de lys covered curtains intact as the fleur de lys was the symbol of the previous monarchy, so he had the curtains re-hung upside down and said the symbol of overthrown royalty was now a bee and his symbol. While this argument may have merit it seems logical that Napoleon’s adoption of the bee was to claim the first kings of the realm’s symbol of authority and to connect himself with that tradition of rule. In many images of Napoleon his bee symbol appears, and he had bees stitched onto his coronation robes.

Napoleon’s claimed connection to the ancient rulers of France went deeper than simply taking some bees as a brand; he forged a connection between his rule and power of the Vatican. The Merovingian rulers were staunchly Roman Catholic and Napoleon knew he needed the support of the Catholic church if his reign over France was to have any kind of power. However, the last Merovingian king was deposed by Pope Zachary in the mid-700s and replaced by Pepin the Short. Pepin was the father of Charles I, who was later known as Charles the Great, Carolus Magnus, and Charlemagne. The list of names Charlemagne was known by didn’t stop there. His titles also included: King of the Franks, protector of the Papacy, ruler of western Europe, and the Father of Europe. The sceptre Napoleon received at his coronation was after the order of Charlemagne and the crown – which wasn’t the same crown used by the Regime Monarchy – was made to look medieval and called the Crown of Charlemagne (it was not the actual crown of Charlemagne).

Next section in audio:

By choosing to connect his power with the Merovingian and Carolingian dynasties, Napoleon had successfully managed to link himself with French national history and the Catholic church. The first kings of France were historically powerful but the fact that that dynasty had been dethroned by the Pope created a complication with the present-day relationship Napoleon would have with the Vatican. By laying claim to the line that the Papacy had set up in place of the Merovingians Napoleon was also using the good will that was still felt by Rome for Charlemagne. Charlemagne was loved, even in the 1700s, by the Catholic church for his protectorship and the Merovingian Dynasty laid claim to the universally loved ideal of ‘firsts’. Napoleon was using his knowledge of his nation’s history to manage some very crafty politics – even though it was harking back to a history that was almost a thousand years old.

Yet even though he so craftily wove a narrative that combined natural-born power and religious power and made a point of inviting the Pope to France to officiate his coronation, Napoleon also acted in a way that really offended the Roman Catholic Church. At the coronation ceremony Napoleon seemed to lose patience waiting for the Pope to give him the crown and throne and simply took the crown and placed it on his own head, crowning himself Emperor of France. Some say that Napoleon was making an Enlightenment-esque statement to the Papacy by crowning himself. Others just say he was impatient and self-important. While this may have been a childish fit of impatience on the part of Napoleon, it seems like someone who so patiently created such a strong narrative regarding who he wanted to emulate as a ruler might have been up to something much more calculated. Understanding the France that he was about to take rule of and knowing his peers’ dedication to the Revolution, his disrespect of the Pope and disregard for the Catholic church’s authority may have been a strategic move to gain the trust and respect of the post-Revolution French people. This is only speculation, however, as there are some things that Napoleon never explained.

As Napoleon began his reign, he ushered in a new aesthetic in the arts called Empire Style. Empire Style took all the elements of Neo-Classical design and added Egyptian aesthetics. While the Fine Arts didn’t feel the impact of Empire Style too directly, architecture and interior design saw more additions of Egyptian motifs being combined with ancient Roman imagery. Empire Style is considered to be a late phase of Neo-Classicism.

As France shifted into a new phase of existence under Napoleon, the Fine Arts saw a shift as its young students sought new themes and inspirations. No longer roused by the ideals of ancient Rome and influenced by Napoleon’s shifted gaze to the history of France, young artists began to look to medieval period for material to use in their imagery. Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres was a gifted student of Jacques-Louis David and during his time as a student Ingres painted Napoleon on his Imperial Throne. The painting was not considered a smash hit at the time as the paint rendering seemed very flat (to us it just looks like an overexposed photograph, but to the eyes of the 1800s it looked flat and washed out) and the imagery all referred back to the Middle Ages, which seemed like an odd choice in a Neo-Classically saturated art world.

“In Ingres painting, Napoleon sits on an imposing, round-backed and gilded throne, one that is similar to those that God sits upon in Jan van Eyck’s Flemish masterwork, the Ghent Altarpiece, 1430-32. It is worth noting that, as a result of the Napoleonic Wars, the central panels of the Ghent Altarpiece that include the image of God upon a throne, were in the Musée Napoléon (now the Louvre) when Ingres painted this portrait.

The armrests in Ingres’s portrait are made from pilasters that are topped with carved imperial eagles and highly polished ivory spheres. A similarly spread-winged imperial eagle appears on the rug in the foreground. Two cartouches can be seen on the left-hand side of the rug. The uppermost is the scales of justice (some have interpreted this as a symbol for the zodiac sign for Libra), and the second is a representation of Raphael’s Madonna della Seggiola from 1513-14, an artist and painting Ingres particularly admired. One final ancillary element should be mentioned. On the back wall over Napoleon’s left shoulder is a partially visible heraldic shield. The iconography for this crest, however, is not that of France, but is instead Italy and the Papal States. This visually ties the Emperor of the French to his position—since 1805—as the King of Italy.

It is not only the throne that speaks to rulership. He unblinkingly faces the viewer. In addition, Napoleon is bedazzled in attire and accoutrements of his authority. He wears a gilded laurel wreath on his head, a sign of rule (and more broadly, victory) since classical times. In his left hand Napoleon supports a rod topped with the hand of justice, while with his right hand he grasps the sceptre of Charlemagne. An extravagant medal from the Légion d’honneur hangs from the Emperor’s shoulders by an intricate gold and jewel-encrusted chain. Although not immediately visible, a jewel-encrusted coronation sword hangs from his left hip. The reason why the sword—one of the most recognizable symbols of rulership—can hardly be seen is because of the extravagant nature of Napoleon’s coronation robes. An immense ermine collar is under Napoleon’s Légion d’honneur medal. Ermine—a kind of short-tailed weasel—have been used for ceremonial attire for centuries and are notable for their white winter coats that are accented with a black tip on their tail. Thus, each black tip on Napoleon’s garments represents a separate animal. Clearly, then, Napoleon’s ermine collar—and the ermine lining under his gold-embroidered velvet robes—has been made with dozens of pelts, a certain sign of opulence. All these elements—throne, sceptres, sword, wreath, ermine, embroidered bees, and velvet—speak to Napoleon’s position as Emperor.

But it is not only what Napoleon wears. It is also how the emperor sits. In painting this portrait, Ingres borrowed from other well-known images of powerful male figures. This ‘type’ showed Zeus seated, frontal, and with one arm raised while the other was more at rest. The low eye level—about that of Napoleon’s knees—also indicates that the viewer is looking up at the seated ruler, as if kneeling before him. The sum total of this painting is not just the coronation of Napoleon, but almost his divine apotheosis. Ingres shows him not just as a ruler, but as omnipotent immortal. Thus, Ingres is working in yet another rich visual tradition, and in doing so, seems to remove Napoleon Bonaparte from the ranks of the mortals of the earth and transforms him into a Greek or Roman god of Mt. Olympus. Never once accused of modesty, there is no doubt that Napoleon approved of such a comparison.”

While students like Ingres began introducing new and non-revolution-related ways to deal with subject matter, artists like Jacques-Louis David worked as a court painter as the First Painter or Official Painter for the Emperor and he began to fade from the political (but not art) scene. Another artist of the Revolution who had never involved himself in politics too openly, Pierre-Paul Prud’hon also found work as a painter for the new ruler of France. One of his commissions was to paint a large portrait of the Empress Josephine of France. It took him four years to paint it. In fact, it took so long that Prud’hon’s wife accused him of being in love with the Empress and ended up flying into such a jealous rage that she was institutionalized. Prud’hon eventually separated from his wife before her death, and had one of his students, fellow artist Constance Mayer (portrait by Prud’hon above) raise his children. Sadness and tragedy seemed to follow Prud’hon as Mayer, who had been a close friend and had raised his children, realized after the death of his wife that he would not marry her and so violently died by suicide. Unfortunately, the Empress Josephine’s marriage to Napoleon was also unlucky. By the time her portrait by Prud’hon was completed Josephine had been divorced by Napoleon for not being able to produce him an heir. Because of this public repudiation, this painting wasn’t shown at the Salon of 1810 because that would have just been awkward. Because she isn’t portrayed as a great and mighty Empress but rather a beautiful, calm woman, some critics agree with Prud’hon’s wife and feel that Prud’hon may have been in love with Rose (as she preferred to be called). Josephine was always held in high regard by Napoleon, except for when he first found out she was prone to having affairs (French life hadn’t really changed all that much apparently), and just before their coronation they nearly dissolved their marriage. Josephine found Napoleon in bed with another woman, a woman Josephine knew, a woman supposed to be a friend to Josephine, and Napoleon flew into a rage at her rage and counter-threatened to divorce her for being infertile. They smoothed things over for a while. However, by 1809, he realized he needed a baby boy and told her that they were getting divorced. Apparently, that was not a pretty dinner conversation as they were both rather loud when angry. A few months later they were divorced. Josephine, as promised by Napoleon, kept her title as Empress of France, but her marriage to Napoleon was over. After the marriage was official ended, Napoleon married Marie-Louise of the Austrian royal family. Napoleon is said to have said that he married a womb, not a wife, when he married his Austrian princess. (He may have never said this, but it makes for a very good story.) The fact that he chose an Austrian princess for his new wife shows that for all its violent revolutionary ways, the culture of France may not have changed all that much at all indeed. Another anecdote of his relationship with Josephine that my or may not be true is that Napoleon died with Josephine’s name on his lips.

In 1811, Prud’hon was commissioned to paint the Emperor’s heir – the child born to him from Marie-Louise. Napoleon nick-named his son The King of Rome and Prud’hon’s painting was full of allegorical references to this young royal’s heritage.

Self-Reflection Questions 2.1 & 2.2

Consider the following questions:

- Do you think the moral & the ‘put the people first’ goals of the Revolution were successful considering the moral & political corruption evident in post-Revolution France?

If those goals were not met, do you think that it was maybe because they were not the true motivations for the uprising?

If they weren’t the true motives, what do you think might have been the ‘real’ reasons behind the violence? - What cautionary tales do you think we, in the 21st century, can take from the climate, actions, and consequences of the French Revolution when we look at our own times and attitudes?

- Howard Ashman, Belle (Los Angeles: Walt Disney Studios, 1991). ↵

- Dr. Susan Waller, "Marie-Guillemine Benoist, Portrait of Madeleine," Smarthistory, September 26, 2018 https://smarthistory.org/benoist-portrait/. ↵

- Waller, "Marie-Guillemine Benoist." ↵

- Dr. Elizabeth Rodini, "2. Museums and politics: the Louvre, Paris," Smarthistory, June 1, 2019, https://smarthistory.org/museums-politic-louvre/. ↵

- Tristan Hopper, “Greatest Cartooning Coup of All Time: The Brit Who Convinced Everyone Napoleon was Short,” National Post (Toronto, Canada) Apr 28, 2016, https://nationalpost.com/news/world/greatest-cartooning-coup-of-all-time-the-brit-who-convinced-everyone-napoleon-was-short ↵

- Hopper. ↵