49 Chapter 12 – Thomas Eakins

Samantha Donovan

Audio recording of chapter is available here:

Thomas Eakins was an American painter who through his career as an artist founded American Realism.[1] “[He] depicted naturalistic scenes of boating, swimming, hunting, surgeons operating, scientists with their apparatus, musicians performing, boxers in the ring.”[2] For his whole career Eakins’ paintings were only of people, places and things he has seen in his daily life.[3] “In his pictures there is nothing unnecessary, nothing meaningless, nothing that is not significant.”[4] His passion was for anatomy, “[for] him the human body was the most beautiful thing in the world – not as an object of desire, or as a set of proportions, but as a construction of bone and muscle.”[5] Eakins studied at Jefferson Medical College for two years to gain a deeper understanding of the human body in order to replicate it in his paintings.[6] Eakins also spent time teaching at the Pennsylvania Academy of Art before he was forced to resign due to his unconventional and revolutionary teaching practices.[7] Eakins’ passion for the human body and his goal of achieving realism was often taken to the extreme. Thomas Eakins was the center of much controversy during his career; he pushed a lot of boundaries and broke many rules but he was a passionate, meticulous artist with great talent and knowledge.

The most problematic of his teaching practices which led to Eakins’ forced resignation from the Pennsylvania Academy of Art was the use of fully nude models for his students, both male and female, to work from in his classes.[8] “In the midst of an impromptu lecture on anatomy in a life study class attended by female students he had impulsively stripped away the loincloth of a male model, leaving nothing to the imagination.”[9] Apart from bringing in nude models for his students to work off of in class, Eakins himself appears in the nude in the photograph, Circle of Eakins.[10] Photographs showcasing both male and female nudity were very much unprecedented at the time and ran the risk of disapproval.[11] “Eakins was breaking all the rules with teaching practices such as these. What we see in the [Circle of Eakins] photograph did not constitute normal studio procedure, not in Philadelphia, nor in Paris.”[12] “While his highly specialized interest in figure construction contributed to his uniqueness as an artist and theoretician, it narrowed the scope of his teaching until it was no longer appropriate for the majority of his students. Eakins’s insistence on a specific course of study limited the flexibility of the curriculum and alienated many pupils. These problems were compounded by his deliberate disregard of conventional Victorian moral standards and by his uncompromising advocacy of intensive professional training for women.”[13] Eakins’ passion for anatomy came across in a way that portrayed him in a very salacious light. It was so comfortable for him to be in the presence of the fully nude body that he failed to respect the boundaries of others in that regard. He was surrounded by much scandal due to his carelessness with nudity and sexuality.

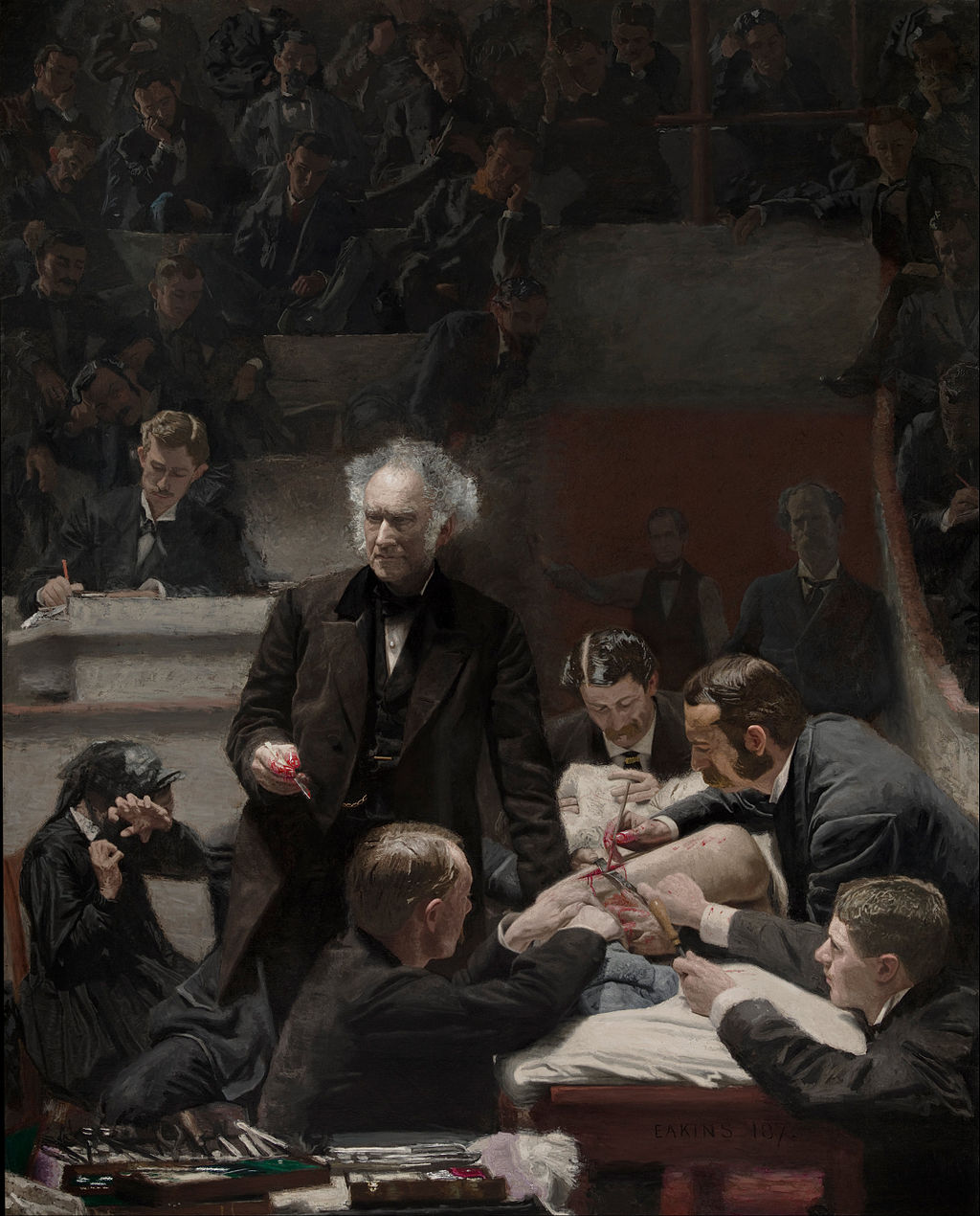

The time that Thomas Eakins spent at Jefferson Medical College he worked alongside professor Samuel Gross, his muse for one of his most famous masterpieces, The Gross Clinic.[14] “The Gross Clinic is eight feet high and six and one half feet wide. It was originally painted [with oil] on a seamless but light weight linen canvas.”[15] Eakins had high hopes for The Gross Clinic in terms of its success at the Centennial Exposition of 1876 but the committee refused to put it on display in the art hall because of its gore and clinical nudity.[16] “Instead they put it in a mock army field hospital, a minor exhibit, foreshadowing rejections that dogged Eakins for the rest of his life.”[17] Eakins admired the ways in which surgeons worked so much that he created intricate works depicting real life scenes of medical procedures. His passion for anatomy would make these particular scenes very fascinating for him but I can understand that not many others would be interested in admiring the details of medical procedures. There was an under-appreciation and misinterpretation of these works because his realistic art was very raw and real.

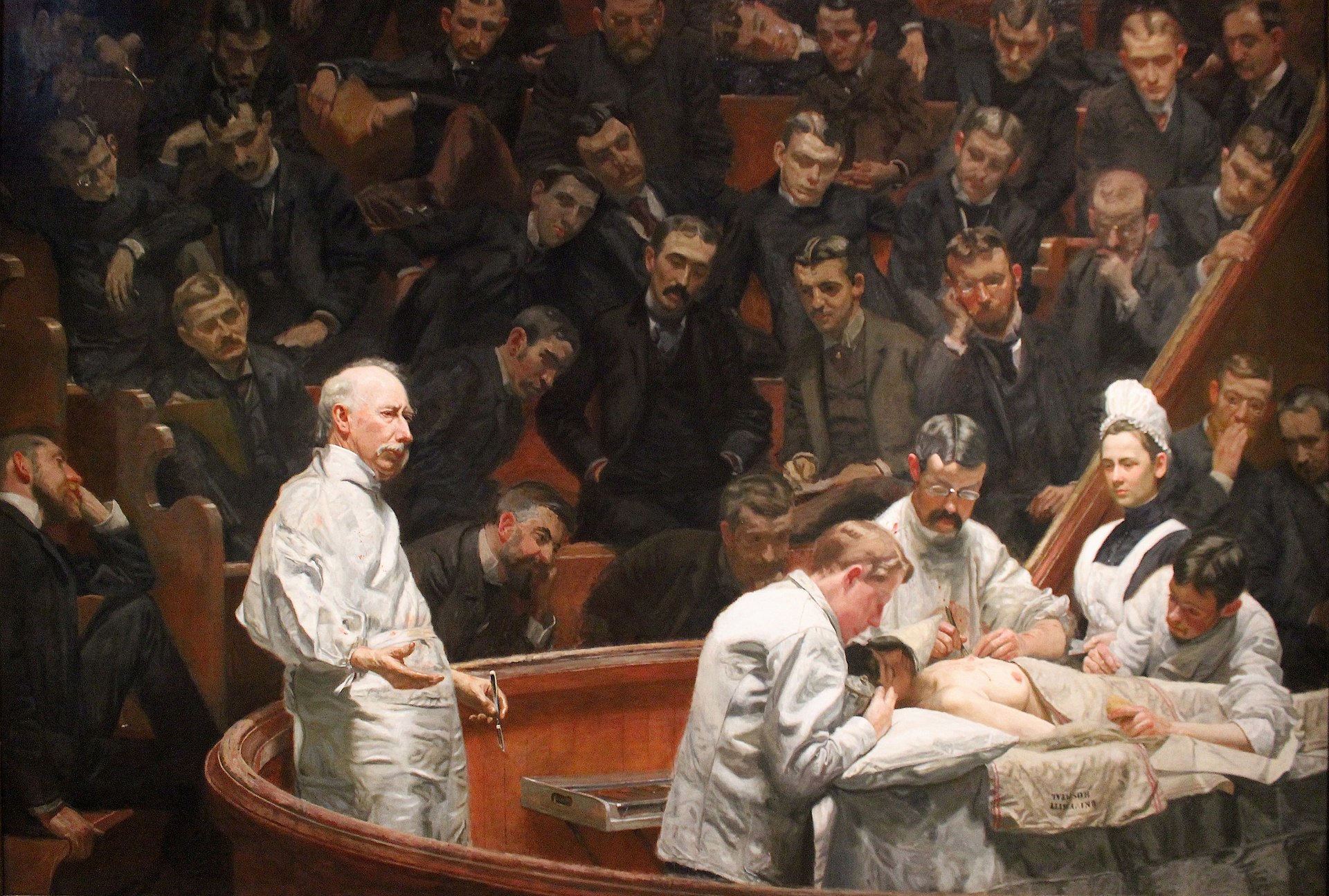

Another one of Thomas Eakins’ popular paintings is The Agnew Clinic. It took Eakins only three months to portray Agnew conducting a clinic for his devoted medical students.[18] The medical procedure being performed in this painting is a mastectomy; this sparked controversy once again for Eakins.[19] It was first deemed revolting and unnecessarily gross and “has more recently been addressed for what has been considered its overly sexist representation of the female body within the realm of medical discourse.”[20] The students in attendance of Agnew’s clinic all possess the ‘gaze’ which represents the hierarchy of male doctor over female patient.[21] The inclusion of a healthy breast in The Agnew Clinic sexualizes and fetishises the patient.[22] Once again, one of Eakins’ works faced criticism because “period medical texts suggest that operating for breast cancer was controversial – not only was the surgery a long, gruelling procedure, but one whose efficacy was questioned.”[23] Even though his similar painting, The Gross Clinic, wasn’t well received he continued to create art that he believed in and was passionate about.

It was nothing close to a dull career for Thomas Eakins. Not only did he submerge himself into a lifestyle of art and education, he navigated his way through a career of controversy and scandal. Eakins was a very inspired man. He took intricate details from many parts of his life and found a way to replicate them for others to appreciate through art and passed along his wisdom to a number of students. Although he had to deal with backlash and judgment from many, his intentions came from a place of passion and genuine curiosity. There is something to be said for a man whose talent is able to stand out above all the criticism and disapproval he was faced with. Although he was a very controversial man, Eakins was a very talented and intentional artist.

Bibliography

Athens, Elizabeth. “Knowledge and Authority in Thomas Eakin’s ‘The Agnew Clinic.’” The Burlington Magazine 148, no. 1240 (2006): 482–85. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20074493.

Canaday, John. “The Realism of Thomas Eakins.” Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin 53, no. 257 (1958): 47-50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3795025.

Davies, Penelope J. E., Walter B. Denny, Frima Fox Hofrichter, Joseph Jacobs, David L. Simon, Ann M. Roberts, H. W. Janson, Anthony F. Janson. Janson’s History of Art: The Western Tradition. Saddle River, NJ: Pearson, 2010.

Doyle, Jennifer. “Sex, Scandal, and Thomas Eakins’s The Gross Clinic.” Representations, no. 68 (1999): 1–33. https://doi.org/10.2307/2902953.

Eakins, Thomas. “The Gross Clinic (1876).” BMJ: British Medical Journal 301, no. 6754 (1990): 707–707. http://www.jstor.org/stable/29709107.

Erwin, Robert. “Who Was Thomas Eakins?” The Antioch Review 66, no. 4 (2008): 655-664. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25475641.

Goodrich, Lloyd. “Thomas Eakins, Realist.” Bulletin of the Pennsylvania Museum 25, no. 133 (1930): 9-17. https://doi.org/10.2307/3794382.

Lippincott, Louise. 2008. “Thomas Eakins And The Academy”. In This Academy: The Pennsylvanian Academy Of Fine Arts 1805-1976.

Lubin, David. “Projecting an Image: The Contested Cultural Identity of Thomas Eakins.” The Art Bulletin 84, no. 3 (2002): 510–22. https://doi.org/10.2307/3177312.

Siegl, Theodor. “The Conservation of the ‘Gross Clinic.’” Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin 57, no. 272 (1962): 39–62. https://doi.org/10.2307/3795054.

[1] Robert Erwin, “Who Was Thomas Eakins?,” The Antioch Review 66, no. 4 (2008): 655, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25475641.

[2] Erwin, “Who Was Thomas Eakins?,” 655.

[3] Lloyd Goodrich, “Thomas Eakins, Realist,” Bulletin of the Pennsylvania Museum 25, no. 133 (1930): 13, https://doi.org/10.2307/3794382.

[4] Goodrich, “Thomas Eakins, Realist,” 17.

[5] John Canaday, “The Realism of Thomas Eakins,” Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin 53, no. 257 (1958): 47, https://doi.org/10.2307/3795025.

[6] Canaday, “The Realism of Thomas Eakins,” 47.

[7] Jennifer Doyle, “Sex, Scandal, and Thomas Eakins’s The Gross Clinic,” Representations, no. 68 (1999): 1, ttps://doi.org/10.2307/2902953.

[8] Penelope J. E. Davies, Denny, Hofrichter, Jacobs, Simon, Roberts, Janson, Janson, Janson’s History of Art: The Western Tradition, Saddle River, NJ: Pearson, 2010, 888.

[9] David Lubin, “Projecting an Image: The Contested Cultural Identity of Thomas Eakins,” The Art Bulletin 84, no. 3 (2002): 510–22. https://doi.org/10.2307/3177312, 516.

[10] Lubin, “Projecting an Image: The Contested Cultural Identity of Thomas Eakins,” 516.

[11] Lubin, “Projecting an Image: The Contested Cultural Identity of Thomas Eakins,” 516.

[12] Lubin, “Projecting an Image: The Contested Cultural Identity of Thomas Eakins,” 516.

[13] Lippincott, Louise. 2008. “Thomas Eakins And The Academy”. In This Academy: The Pennsylvanian Academy Of Fine Arts 1805-1976, paragraph 2.

[14] Thomas Eakins, “The Gross Clinic (1876),” BMJ: British Medical Journal 301 no. 6754 (1990): 707, http://www.jstor.org/stable/29709107.

[15] Theodor Siegl, “The Conservation of the ‘Gross Clinic,’” Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin 57, no.272 (1962): 39, https://doi.org/10.2307/3795054.

[16] Erwin, “Who Was Thomas Eakins?,” 656.

[17] Erwin, “Who Was Thomas Eakins?,” 656.

[18] Elizabeth Athens, “Knowledge and Authority in Thomas Eakin’s ‘The Agnew Clinic.’” The Burlington Magazine 148, no. 1240 (2006): 482–85. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20074493.

[19] Athens, “Knowledge and Authority in Thomas Eakin’s ‘The Agnew Clinic,’” 482.

[20] Athens, “Knowledge and Authority in Thomas Eakin’s ‘The Agnew Clinic,’” 482.

[21] Athens, “Knowledge and Authority in Thomas Eakin’s ‘The Agnew Clinic,’” 482.

[22] Athens, “Knowledge and Authority in Thomas Eakin’s ‘The Agnew Clinic,’” 485.

[23] Athens, “Knowledge and Authority in Thomas Eakin’s ‘The Agnew Clinic,’” 485.