46 Chapter 12 – Alphonse Mucha’s The Slav Epic

Kristina M. Miko

Audio recording of chapter available here:

Alphonse Mucha was born on 24th, July 1860 at Ivancice in Moravia, then a province of the vast Habsburg Empire.[1] During his time as an artist Mucha created mainly posters and illustrations for the public.[2] Such famous examples are the poster of “for Sarah Bernhardt in the role of Gismonda” and “Job” for a cigarette company.[3] He mainly worked in Paris but as a passionate Czech patriot he would have also been unhappy to be known as a “Parisian” artist.[4] During Mucha’s life in Czechoslovakia, the empire was already falling apart at the seams under the pressures of the burgeoning nationalism of its multi-ethnic component parts.[5] In the year before Mucha’s birth, nationalist aspirations throughout the Habsburg Empire were encouraged by the defeat of the Austrian army in Lombardy that preceded the unification of Italy.[6] It was symptomatic of the Czech nationalist struggle against the German cultural domination of Central Europe that the text of Dalibor had to be written in German and translated into Czech.[7] From Alphonse Mucha’s earliest days growing up, the political world would heavily influence in his creations of The Slav Epic. The Slav Epic would be one of Mucha’s greatest accomplishments late in his career in honouring his culture and expressing the political ups and downs that the Slavs have had throughout their history.

When did Alphonse Mucha create these paintings? The idea came to him in 1899.[8] Mucha was working on the design for the interior of the Pavilion of Bosnia-Herzegovina, which had been commissioned by the Austro-Hungarian government for the Paris Exhibition of 1900.[9]

Preparing the project, he travelled through the Balkans, researching their history and customs as well as observing the lives of the Southern Slavs in the regions that had been annexed by Austria-Hungary two decades earlier.[10] From his travels this gave him the inspiration for the creation of “an epic for all the Slavonic peoples” that would portray the happiness and sorrows of his own country and those of all the other Slavs.[11]

Between 1911 and 1926 Mucha’s time was taken up with the creation of the Slav Epic.[12] For this project he rented a studio and an apartment in Zbiroh Castle in Western Bohemia.[13] This gave Mucha the benefit from the spacious studio enabling him to work on the large canvases that he needed to complete.[14] In the series, Mucha depicted twenty key moments from the Slavic past, ancient to modern, ten of which depict moments from Czech history and ten on historical episodes from other Slavonic regions.[15]

Why did Alphonse Mucha create these paintings? Going back to the beginnings of his childhood he was heavily influence by the politics of his nation and the history that holds with it. With the ‘Slav Epic’ Mucha wished to unite all the Slavs through their common history and their mutual reverence for peace and learning and eventually to inspire them to work for humanity using their experience and virtue.[16] In 1928, Mucha officially presented the complete series of the Slav Epic to the City of Prague as a gift to the nation, coinciding with the 10th Anniversary of its independence.[17]

The Slav Epic is a series of twenty large paintings on canvas (the largest measuring over 6 by 8 metres) depicting the history of the Slav people and civilization.[18] The first canvas in the series, The Slavs in Their Original Homeland, was finished in 1912 and the entire series was completed in 1926 with the final canvas, The Apotheosis of the Slavs, which celebrates the triumphant victory of all the Slavs whose homelands in 1918 finally became their very own.[19] Mucha conceived his paintings as a monument for all the Slavonic peoples and he devoted the latter half of his artistic career to the realization of this work.[20]

What is interesting in these paintings? I would like to discuss about 2 paintings in particular that I have found interesting. The first is The Slavs in Their Original Homeland: Between the Turanian Whip and the Sword of the Goths (1912).[21] Mucha chose to start his history of the Slavic people in the 4th to 6th centuries.[22] At this time, the Slavic tribes were agricultural folk who lived in the marshes between the Vistula River, the Dnepr River, the Baltic Sea, and the Black Sea.[23] With no political structure to support them, their villages were under constant attack by Germanic tribes from the West who would burn their houses and steal their livestock.[24] The couple hiding in the bushes in the foreground as their village burns on the horizon are the survivors of one of these attacks.[25] The fear and vulnerability expressed in their faces beseeches the help of the viewer.[26] A pagan priest flanked by two youths symbolising war and peace floats in the top right of the composition.[27] These figures foretell the peace and freedom that will come to the Slav people when independence is gained through war.[28]

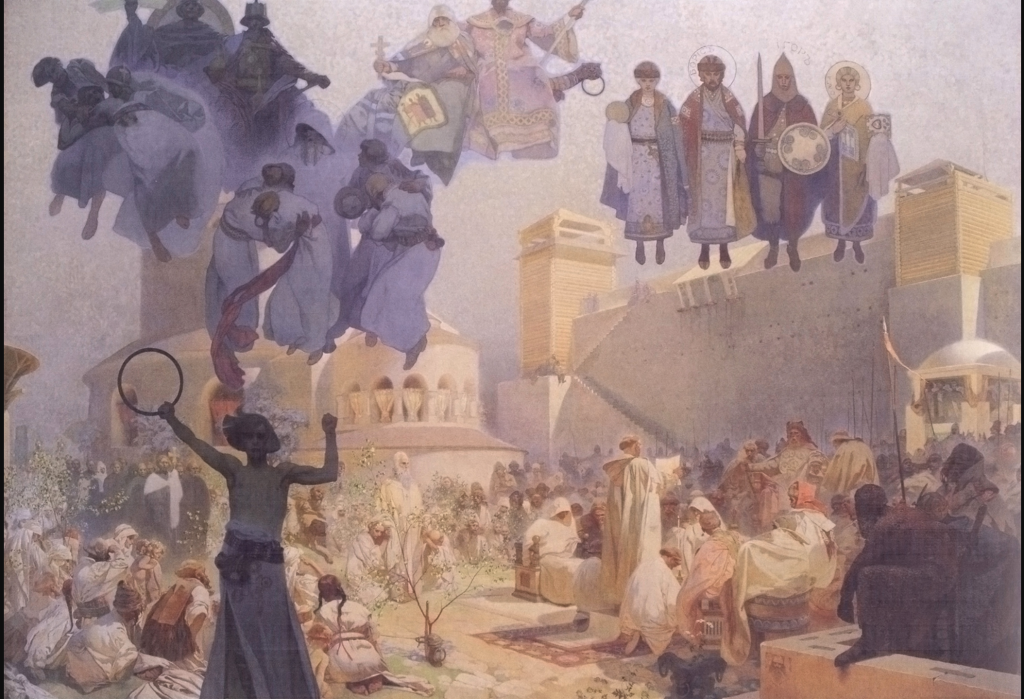

The next painting is the Introduction of the Slavonic Liturgy: Praise God in Your Mother Tongue.[29] German Christian missionaries led a crusade throughout the Moravian Empire in the second half of the 8th century.[30] In an attempt to prevent the demise of the Slav language, Prince Rostislav engaged two learned monks from Salonika, Cyril and Methodius, to translate the Bible into Old Church Slavonic.[31] This move was opposed by German bishops and Methodius had to travel to Rome to defend the translation.[32] He succeeded in securing Rome’s permission to continue his work and was appointed archbishop of Great Moravia for his efforts.[33] Methodius and Cyril’s translation was instrumental in the survival of the Slavic tongue in subsequent centuries, and they became the Slav people’s most popular saints.[34] This composition depicts the triumphal return of Methodius to Great Moravia from Rome.[35] Methodius is the bearded figure to the left of the centre supported by two of his followers.[36] Prince Rostislav’s successor, Prince Svatopluk, sits on a throne to the far right of the composition and listens as a priest reads a letter from the pope.[37] Represented in the top right of the painting are the stylised figures of rulers who supported the spread of Christianity in the Slavic language: Boris of Bulgaria and Igor of Russia and their wives. In the foreground, a figure of a youth with a clenched fist and a circle in his right hand symbolises the strength and unity of the Slav people.[38]

Mucha clearly has a soft spot for where he was born and raised as a proud Czechoslovakian. With strong political ties to his homeland, it is clear that he wanted to contribute something for his people. Though there are still another eighteen paintings of history that haven’t been discussed here I would encourage anyone who is interested in the paintings to look at them. Mucha may have chosen a completely different topic from his typical poster illustrations but Mucha’s Art Nouveau style can still be seen in the strong lines contouring his characters, and the organic, flowing colour scheme in each painting. The Slav Epic is one of Mucha’s greatest accomplishments for his people, honouring his culture and expressing the happiness and sorrows the Slav’s have had throughout their history.

Bibliography

Bade, Patrick, and Victoria Charles. Alphonse Mucha. New York: Parkstone International, 2013.

Özaltun, Gözde “The Mystery Behind Alphonse Mucha’s Works: A comparative Analysis of Art Nouveau Artists.” Electronic Turkish Studies 17, no.3 (2022): p583-613. 10.7827/TurkishStudies.57952.

Potter, Polyxeni. “Fine Art and Good Health for the Masses,” Emerging Infectious Diseases 12, no. 7 (2006): p1182-83.10.3201/eidl207_AC1207.

Salcman M; Osher Institute, Townson University Baltimore, Maryland. “Zodiac (1986) by Alphonse Mucha (1860-1939),” Neurosurgery 76, no. 5 (2015): p499-504, 10.1227/NEU.0000000000000731.

“Slav Epic”, Accessed October 2, 2022, Mucha Foundationhttp://www.muchafoundation.org. /gallery/themes/theme/slav-epic.

Young, Gertrude M. “Alphonse Mucha, The Czecho-Slovac Painter,” The Brooklyn Museum Quarterly 8, no.2. (1921) p56-61, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26459452.

- Patrick Bade and Charles Victoria, Alphonse Mucha, (New York: Parkstone International, 2013), n.p. ↵

- Bade and Victoria. Alphonse Mucha. n.p. ↵

- Bade and Victoria, Alphonse Mucha, n.p. ↵

- Bade and Victoria, Alphonse Mucha, n.p. ↵

- Bade and Victoria, Alphonse Mucha, n.p. ↵

- Bade and Victoria, Alphonse Mucha, n.p. ↵

- Bade and Victoria, Alphonse Mucha, n.p. ↵

- Slav Epic-Themes-Gallery-Mucha Foundation. “Themes: Slav Epic.” accessed October 2, 2022, http://www.muchafoundation.org/en/gallery/themes/theme/slav-epic. ↵

- Slav Epic-Themes-Gallery-Mucha Foundation. “Themes: Slav Epic.” ↵

- Slav Epic-Themes-Gallery-Mucha Foundation. “Themes: Slav Epic.” ↵

- Slav Epic-Themes-Gallery-Mucha Foundation. “Themes: Slav Epic.” ↵

- Slav Epic-Themes-Gallery-Mucha Foundation. “Themes: Slav Epic.” ↵

- Slav Epic-Themes-Gallery-Mucha Foundation. “Themes: Slav Epic.” ↵

- Slav Epic-Themes-Gallery-Mucha Foundation. “Themes: Slav Epic.” ↵

- Slav Epic-Themes-Gallery-Mucha Foundation. “Themes: Slav Epic.” ↵

- Slav Epic-Themes-Gallery-Mucha Foundation. “Themes: Slav Epic.” ↵

- Slav Epic-Themes-Gallery-Mucha Foundation. “Themes: Slav Epic.” ↵

- Slav Epic-Themes-Gallery-Mucha Foundation. “Themes: Slav Epic.” ↵

- Slav Epic-Themes-Gallery-Mucha Foundation. “Themes: Slav Epic.” ↵

- Slav Epic-Themes-Gallery-Mucha Foundation. “Themes: Slav Epic.” ↵

- Slav Epic-Themes-Gallery-Mucha Foundation. “Themes: Slav Epic.” ↵

- Slav Epic-Themes-Gallery-Mucha Foundation. “Themes: Slav Epic.” ↵

- Slav Epic-Themes-Gallery-Mucha Foundation. “Themes: Slav Epic.” ↵

- Slav Epic-Themes-Gallery-Mucha Foundation. “Themes: Slav Epic.” ↵

- Slav Epic-Themes-Gallery-Mucha Foundation. “Themes: Slav Epic.” ↵

- Slav Epic-Themes-Gallery-Mucha Foundation. “Themes: Slav Epic.” ↵

- Slav Epic-Themes-Gallery-Mucha Foundation. “Themes: Slav Epic.” ↵

- Slav Epic-Themes-Gallery-Mucha Foundation. “Themes: Slav Epic.” ↵

- Slav Epic-Themes-Gallery-Mucha Foundation. “Themes: Slav Epic.” ↵

- Slav Epic-Themes-Gallery-Mucha Foundation. “Themes: Slav Epic.” ↵

- Slav Epic-Themes-Gallery-Mucha Foundation. “Themes: Slav Epic.” ↵

- Slav Epic-Themes-Gallery-Mucha Foundation. “Themes: Slav Epic.” ↵

- Slav Epic-Themes-Gallery-Mucha Foundation. “Themes: Slav Epic.” ↵

- Slav Epic-Themes-Gallery-Mucha Foundation. “Themes: Slav Epic.” ↵

- Slav Epic-Themes-Gallery-Mucha Foundation. “Themes: Slav Epic.” ↵

- Slav Epic-Themes-Gallery-Mucha Foundation. “Themes: Slav Epic.” ↵

- Slav Epic-Themes-Gallery-Mucha Foundation. “Themes: Slav Epic.” ↵

- Slav Epic-Themes-Gallery-Mucha Foundation. “Themes: Slav Epic.” ↵