23 Chapter 10 – Suzanne Valadon

Post-Impressionism

Morgan Hunter

Audio recording of the full chapter can be found here: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1K3azfXC6RNV8u1gYyaweLNQaJk4Gdo5F/view?usp=sharing

Beneath the beautiful colours of paint, there is a blank canvas that comes in all shapes and sizes. This blank canvas turns into one of many layers of beauty with extravagant colours and textures, yet there still lay imperfections within it, because no matter how hard one might try, imperfections are what makes us human. No female body goes without a flaw, that is what makes all women beautiful and unique in their own way. Yet, what is the flaw? Throughout history, women were portrayed as having this perfect figure that would catch any man’s eye, with no “perceived” imperfection in sight. This created the ideology of a perfect body, something that is intangible as it is only in the eye of the beholder. A woman’s shape is endlessly unique and therefore subject to debate over one definition of beauty. Suzanne Valadon changed history with her artistic mind, she contradicted the ongoing ideology of beauty by portraying a realistic view of women and their bodies. Suzanne Valadon climbed the ladder into the art community and created unique artwork that was unlike any other. Her portrayal of art was unlike any other and had deeper meaning that even feminists today reflect on. Valadon, a woman who knew a change needed to happen.

To fully grasp the concept of who Suzanne Valadon was and what her art work meant, readers need to know her past. Marie Clementine, who later became the well-known Suzanne Valadon, was born in the middle working class, a far cry from the distinct art community. Her journey into the art world was unlike most artists but by no means not well deserved. Due to being born in that middle working class, Marie did not have a comfortable income that could pay for artistic training, her dreams would have to be put aside. But with that being said, she became invaluable to an artist, the model, “She needed to approach the business from the other side of the canvas: she would have to become a model.” [1] Her modelling career began because her beauty could not go unnoticed. Famous artists even sought her out, “A petite and luminous beauty, she soon found work as an artist’s model, posing for (and in many cases having affairs with) the painters whose names came to define that moment in art history.” [2] Marie was now in the art world, just in an alternative way.

This arose a new phase in her life; but not the one she hoped for in terms of her self image and respectability, “The model offered her body for sale.” [3] Her beauty was used for male satisfaction, and she was seen as no more than just a woman with a beautiful figure on a piece of canvas. Marie Clementine now became Suzanne Valadon, “Toulouse-Lautrec suggested that the name “Suzanne” might be better suited to her career as an artist’s model.” [4] But, what they did not realize then, was Suzanne Valadon would not only be the name of a famous model but the name of a woman who changed the art world with her own paintings.

![Par Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec — [1], Domaine public, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1393659](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6b/Portrait_de_Suzanne_Valadon_par_Henri_de_Toulouse-Lautrec.jpg/1024px-Portrait_de_Suzanne_Valadon_par_Henri_de_Toulouse-Lautrec.jpg)

While painters were objectifying and critiquing her female form on canvas, she analyzed them, eventually teaching herself how to become an artist, “She had no formal artistic education, but taught herself to draw by watching artists, and particularly by modelling them.” [5] It was actually the man who suggested she change her name for modelling, who pushed her to become more than just a beautiful figure on canvas, “It was Toulouse-Lautrec who first encouraged her intellectual and artistic development.”[6] This was something unheard of. “Rare was the model who progressed beyond the passive object of the male artist’s gaze to become an artist herself (Burns 1991-1992).” [7] Her artistic focus is what really created her spot in the art community though. Instead of playing it safe, she chose a category that was male dominated, the female nude, “Women were not only excluded from formal study of the nude but also from the power to determine the definition o f high art.”[8] Being a woman did not stop Suzanne Valadon, it only made her want to depict how a female body should be portrayed and how the concept of beauty comes in many forms. Her idea of the female body created a whole new meaning to the word “nude” in the art community.

To understand Suzanne Valadon, we must first see her past. As a model, she experienced first hand how women and their own unique bodies were objectified on canvas until deemed perfection. She used that experience to create a whole new ideology, which is truly amazing.

![By Suzanne Valadon - [1], Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3421744](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/b1/Suzanne_Valadon_-_Nus.jpg)

In order to see how Suzanne Valadon’s artwork had a completely unique take on the female nude, an analysis of the previous male dominated nude is required. Before Suzanne Valadon started her artistic journey, the depiction of the female nude was totally male dominated and made for the male population, “Female images are produced for consumption by male spectators.”[9] Women’s bodies were objectified on a piece of canvas until they were absolutely perfect, with no flaw in sight. They depicted women as these sexual figures who only lived for male attention,”…the glimpse of her breast and the expanse of her buttocks and thighs emphasize her sexual availability.” [10] “It suggests that the woman in the image is literally possessed by the man who looks at her.” [11] Ultimately, the female nude was usually depicted by a perfect female figure in a luring, sexual position and setting, almost like she was awaiting or calling a male figure. This kind of nude created its own ideology about what “beauty” had to be or look like, a standard almost no woman could or should have to reach. The typical nudist structure followed the same format, a woman laying seductively across the painting, inviting male attention.

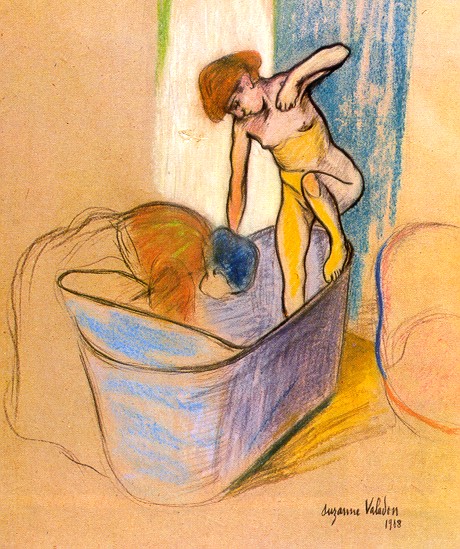

Suzanne Valadon’s artwork did not follow that typical structure at all. She had a totally different idea in mind. Her art work contradicted that ideology of the female nude, “Often her paintings of nudes are stripped of any erotic overtones and thus resist the sexually charged male gaze.” [12] She changed the whole concept, which included how a woman’s body was shown, the position she was in as well as the setting and details in the background. In her paintings with primarily the use of oil paint, oil pencils, pastels, she highlighted a woman’s natural curve, she painted women doing everyday things and lastly she put objects in the painting that were far from anything sexual or luring. A perfect example of this is her painting, Nude Grandmother and Young Girl Stepping into the Bath (1908). Like the name states, this nude features a young girl completely naked stepping into the bathtub with her grandmother by her side. The young girl is not in an inviting, sexual pose, she was just simply doing an everyday task with her elderly grandmother sitting by her side. Suzanne Valadon’s artistic mind differed so much from artists before her because of her decision to portray a natural woman in her habitat.

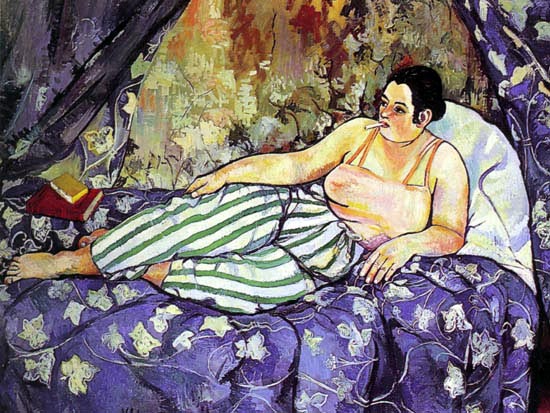

Valadon’s artwork was so much more than just a picture on canvas. It challenged the that time’s ideology of what “beauty” was or had to be, something that was honestly impossible. No women’s body is the same, nor is any considered to be less beautiful. Every flaw, curve, and sag a woman has just makes her that much more unique. This was what Valadon highlighted, and this is how she changed history. Her artwork proved beauty comes at any age, any body type and that a woman’s body doesn’t always have to be objectified for the male population, it can be depicted as women just doing ordinary things, without calling for sexual intention, “This suggests a conscious and deliberate attempt to change existing codes of representation which, in the case of the female nude, emphasized beauty of form, harmony and time.” [13] Ultimately, she normalized women’s sexuality and painted the female nude for females, not for male satisfaction, “But what she did do was to open up different possibilities within the painting of the nude to allow for the expression of women’s experience of their own bodies.” [14] This meant a new beginning.

The nude now had a new purpose; to depict a woman in her, not a man’s, natural habitat, “Unlike their male contemporaries, they expressed the conflicts of their feminine self-image. Their work tells us something of what it is like to be a modern woman rather than what modern men wish women were like.” [15] Looking at Valadon’s artwork and not seeing the meaning behind the nude paintings, is like seeing only the tip of the iceberg.

Suzanne Valadon, a model turned into an artist, forever changed the female nude with her artistic, female centered mind. She found a way into the art community with no artistic training, created artwork with a completely different structure and used that art to create a whole new ideology. There can be no beauty without flaw. Women’s bodies were not meant to be objectified, nor made solely for the male population. A woman’s body is her own, which is exactly what Suzanne Valadon proved.

Bibliography

Betterton, Rosemary. “How Do Women Look? The Female Nude in the Work of Suzanne Valadon.” Feminist Review 3, no. 19 (1985): 3-24, https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/1394982.pdf

Burns, Janet. “Looking as Women: The Paintings of Suzanne Valadon, Paula Modersohn-Becker and Frida Kahlo.” Atlantis 18, no. 1 & 2 (1991-1992): 25-46, https://journals.msvu.ca/index.php/atlantis/article/view/5167/4365

Egon, Moira. “Ekphrasis: seven after Suzanne Valadon.” New Criterion 35, no. 8 (2017): 38, https://content.ebscohost.com/ContentServer.asp?T=P&P=AN&K=122288007&S=R&D=a9h&EbscoContent=dGJyMNLr40Sep7M40dvuOLCmsEiep7NSsam4SK6WxWXS&ContentCustomer=dGJyMPGuslCyp7VQuePfgeyx43zx

Hewitt, Catherine. Renoir’s Dancer: The Secret Life of Suzanne Valadon. New York: St. Martin’s Press 2018. 149. https://books.google.ca/books?hl=en&lr=&id=YNouDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP9&dq=life of suzanne valadon&ots=C6jxLW5_C4&sig=GyQbkL4XdE4cV1egoGYMwmffA6Y&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=life of suzanne valadon&f=false

Hunt, Courtney. “Wicked, Hard and Supple: An Examination of Suzanne Valadon’s Nude Drawings of Young Maurice.” Art Inquiries 17, no. 4 (2019): 410–22, https://kb.osu.edu/bitstream/handle/1811/91581/HuntC_ArtInquires_xv2019_410-422.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Mathews, Patricia. “Returning The Gaze: Diverse Representations of the Nude in the Art of Suzanne Valadon.” The Art Bulletin 73, no. 3 (1993): 416-430,https://content.ebscohost.com/ContentServer.asp?T=P&P=AN&K=9112091984&S=R&D=f5h&EbscoContent=dGJyMMvl7ESep7I40dvuOLCmsEieqK5Ssqq4S7SWxWXS&ContentCustomer=dGJyMPGuslCyp7VQuePfgeyx43zx

Polinska, Wioleta. “Dangerous Bodies: Women’s Nakedness and Theology.” Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion 16, no. 1 (2000): 45-62, https://www.jstor.org/stable/25002375?seq=13#metadata_info_tab_contents

- Catherine Hewitt, Renoir’s Dancer: The Secret Life of Suzanne Valadon (New York: St. Martin’s Press (2018): 149. ↵

- Moira Egon, “Ekphrasis: Seven after Suzanne Valadon,” New Criterion 35, no. 8 (2017): 38. ↵

- Janet Burns, “Looking as Women: The Paintings of Suzanne Valadon, Paula Modersohn-Becker and Frida Kahlo.” Atlantis 18, no. 1 & 2 (1991-1992): 31. ↵

- Egon, “Ekphrasis,” 38. ↵

- Patricia Mathew, “Returning The Gaze: Diverse Representations of the Nude in the Art of Suzanne Valadon.” The Art Bulletin 73, no. 3 (1993): 415. ↵

- Burns, “Looking as Women,” 31. ↵

- Burns, “Looking as Women,” 31. ↵

- Burns, “Looking as Women,” 28. ↵

- Burns, “Looking as Women,” 26. ↵

- Rosemary Betterton, “How Do Women Look? The Female Nude in the Work of Suzanne Valadon.” Feminist Review 3, no. 19 (1985): 5. ↵

- Betterton, “How Do Women Look?” 5. ↵

- Wioleta Polinska. “Dangerous Bodies: Women’s Nakedness and Theology.” Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion 16, no. 1 (2000): 57. ↵

- Burns, “Looking as Women,” 15. ↵

- Burns, “Looking as Women,” 22. ↵

- Burns, “Looking as Women,” 33. ↵