30 Chapter 10 – Henri Matisse

Henri Matisse and Modern Art

Taylor Dennis

Audio recording of this chapter available here:

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder. At least that’s what they always told us, right? When Henri Matisse began as an artist, artwork was predominately celebrated for realism and the historical scenes they depicted. There were much more objective, rigid ideas of what made art “good”. Matisse however, started off with classical art knowledge and worked backward to elicit a modern take of the subject. Henri Matisse went on to influence the concept and definition of modernism in his art and in his life. This is demonstrated in his letters with Walter Pach, his transition to cut-out art, and the careful planning he put into his work.

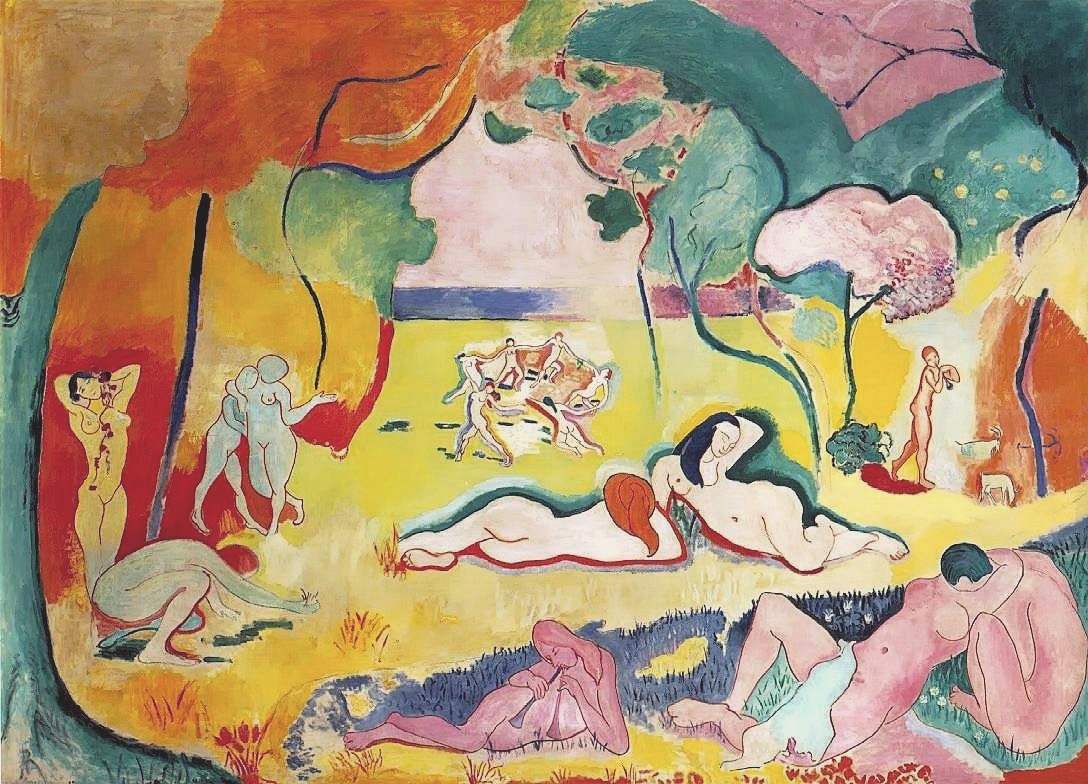

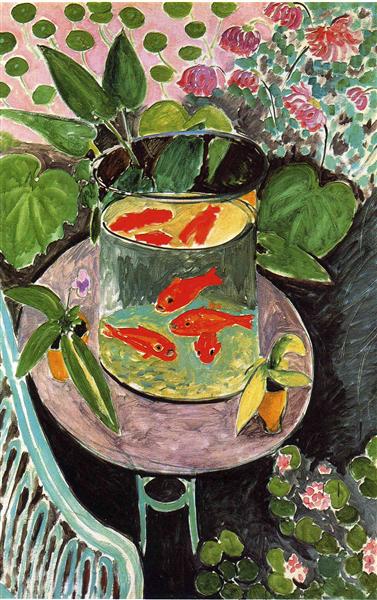

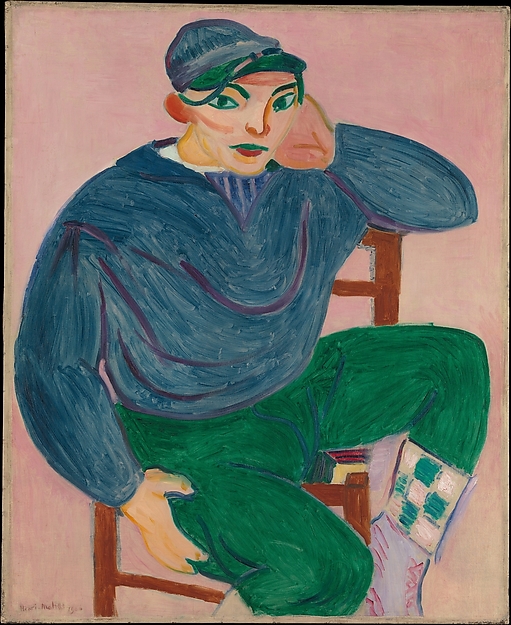

Modernism is all about breaking away from classical ideals and paradigms. Which was exactly what Matisse did. He devolved his work, changing proportions, focal points, colours, and mediums to elicit emotion in the audience. Some of his collections demonstrated this progression, like Interior with Goldfish and Goldfish and Palette where Matisse started off with a room scene where the goldfish merely was, and then made the goldfish the focal point and the room around it abstract. He demonstrates this again with Young Sailor I and Young Sailor II, where she starts off in Young Sailor I with a more tradition and realistic portrait and decomposes it to be flatter, less dimensional, and far more modern. Young Sailor II, while far less realistic is a soulful and expressive capturing of the young fisherman which was become far more famous than the former.

In addition to the work he created that influenced other artists he founded the Matisse Academy and coached other artists in modern techniques, as seen in his letters to Walter Pach.[1] In one of his later letters Matisse writes “a modern painting has no need for a frame”, after Pach wrote Matisse asking what frame he should use for one of his works.[2] From these letters we can clearly see that Matisse had well developed ideas of what modernism could be and was eager to influence other artists as they helped develop the style. He also had his own academy for young artists in France where he taught them and influenced their art for many years.

Part of Matisse’s modern work was the use of different mediums, Matisse created an extensive cut out art collection. Sometimes described as “drawing (or painting) with scissors” because of his artistry and ability to capture form and evoke emotion.[3] His work in cut-out art began when he was bed-ridden with cancer.[4] Like, the style of modernism, Matisse adapted and took on this new form of expressing his artistic vision rather than allowing himself to held back by the cultural ideals around what art should be. This act alone gives me so much respect for Matisse, and his courageous creative vision. He made more than 200 cut outs during his time and as he went, they grew in size and grandeur, many of which were installed on walls. He felt this time was ‘his second life’ and this work reflects the joy he had for the world around him.[5]

While modern art was often seen as a less developed or sophisticated form than traditional styles, Matisse put great care and attention into his work. He created works that appeared spontaneous but were actually carefully crafted and designed. Matisse studied the female form and particularly, the movement of the body dancing, so much so that his work has even been compared to a dancer on display. Sue Karen Smith in her article: Masterworks in Progress: Exploring the Mind, and Work, of Henri Matisse wrote, “Like a toned dancer, Matisse could produce his work only after submitting to an arduous process”.[6] As we can see from his extensive sketches and drawing, Matisse put great care and attention into every element of his work to capture more than just the realistic scene a like many of the painters before him. And in his later cut-out work, the many pinholes reveal the same thing, that Matisse adjusted and adapted his pieces many times before they were glued down.[7] Although his work looked spontaneous and sometimes abstract, Matisse was had a precise vision and often restarted projects if they weren’t quite right.

In the end, Henri Matisse not only created influential and modern works, but he embodied the ideals himself. He was a living example of resilience when he transitioned too cut-out work in his illness, and he brought life and happiness into his art. Since his time, art has progressed a long way and is respected as subjective and challenging, Matisse helped fuel that change. Matisse was adaptive, creative, and passionate about capturing the essence of everyday life and displaying it for us to enjoy.

My Favourite Henri Matisse

While I love all the cut outs, my favourite is the blue nude collection: standing, sitting, and hair in the wind. They’re so carefree and raw without being obscene. I feel the emotion: distress, exhaustion, and joy when I look at them. They feel carefree, seen and beloved but not exposed, at least not shamefully. They are presented honestly but not at expense of themselves.

I can only imagine that this is exactly how Henri wanted me to see them. He must have seen so much beauty and grace around him to capture the world with the colours and bold lines of his cut-outs. I am glad that we get to enjoy his perspective and outlook on life in his work to this day. Thanks Henri.

To see Matisse’s Blue Nude II from 1952 check out this webpage from the Museum of Modern Art:

Bibliography

Borg, M B ter. “Sense Giving in the Art of Henri Matisse.” Implicit Religion 19, no. 1 (2016): 55–60. doi:10.1558/imre.v19i1.30005.

Crooker, Barbara Poti. “Sketch for ‘Le Bonheur De Vivre,’ 1905: The Happiness of Life, Henri Matisse.” Italian Americana 34, no. 1 (2016): 67. Accessed October 26, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43926875.

D., and W. S. L. “Henri Matisse.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 61, no. 4 (2004): 25-41. Accessed October 19, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3269127.

Matisse, Henri, Gail Levin, and John Cauman. “Researching at the Archives of American Art: Henri Matisse’s Letters to Walter Pach.” Archives of American Art Journal 49, no. 1/2 (2010): 28-41. Accessed October 25, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23025799.

O’Donovan, Leo J. “Risking Everything: Henri Matisse’s Truest Expressions.” America 203, no. 5 (2010): 20–22. https://search-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.ardc.talonline.ca/login.aspx?direct=true&db=reh&AN=CPLI0000513104&site=eds-live.

Smith, Karen Sue. “Masterworks in Progress: Exploring the Mind, and Work, of Henri Matisse.” America 208, no. 5 (2013): 24–26. https://search-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.ardc.talonline.ca/login.aspx?direct=true&db=reh&AN=CPLI0000539048&site=eds-live.

Weston, Neville. “Henri Matisse: The Cut-Outs.” Craft Arts International, no. 92 (October 2014): 69. https://search-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.ardc.talonline.ca/login.aspx?direct=true&db=f5h&AN=99647119&site=eds-live.

- Henri Matisse, Gail Levin, and John Cauman. Researching at the Archives of American Art: HENRI MATISSE'S LETTERS TO WALTER PACH. Archives of American Art Journal: 2010, 49, no. ½: 28-41. ↵

- Henri Matisse, Gail Levin, and John Cauman. Researching at the Archives of American Art: HENRI MATISSE'S LETTERS TO WALTER PACH. Archives of American Art Journal: 2010, 49, no. ½: 28-41. ↵

- 3. Weston Neville. “Henri Matisse: The Cut-Outs.” Craft Arts International: 2014, no. 92: 69. ↵

- Weston Neville. “Henri Matisse: The Cut-Outs.” Craft Arts International: 2014, no. 92: 69. ↵

- Weston Neville. “Henri Matisse: The Cut-Outs.” Craft Arts International: 2014, no. 92: 69. ↵

- Weston Neville. “Henri Matisse: The Cut-Outs.” Craft Arts International: 2014, no. 92: 69. ↵

- Weston Neville. “Henri Matisse: The Cut-Outs.” Craft Arts International: 2014, no. 92: 69. ↵