16 Chapter 9 – Berthe Morisot

Berthe Morisot: An Artist Of Her Time

Destiny Mykyta (née Jackson)

Audio recording of the full chapter can be found here: https://drive.google.com/file/d/15d48q9qDs9qth6Gdm8T4tI_yiEKwrIDs/view?usp=sharing

Berthe Morisot’s art and career were shaped entirely by the fact that she was a woman living in the 1800s. Born into an upper-middle-class bourgeoisie family, Morisot was provided opportunities and experiences that allowed her to foster her artistic abilities and pursue a career unusual for a woman in her time. Morisot’s womanhood influenced every aspect of her personal and professional life, touching every facet of her relationships with her parents, siblings, male friends, and colleagues. Morisot’s trajectory in career, life, artistic choice, and subject matter all could have been drastically different were she afforded the same opportunities and privileges as a man. Because of Morisot’s unique experience, that of an upper-class woman in the 1800s, she was able to combine her hard work and talent and share with the world an artistic perspective that had never been offered before. By doing so, she cemented herself as a pioneer and an important figure in the Impressionist movement.

Berthe Morisot was born in 1841 to Tiburce Morisot and Marie-Cornelie (née) Thomas.[1] Both of her parents came from well-to-do families, and Morisot’s father maintained a career in government throughout her childhood.[2] Morisot was encouraged to enjoy literature, drawing, clay modelling, and lessons in piano and was sent to an exclusive private school in Passy when her family moved there in 1855.[3] These were the sorts of experiences afforded to someone of Morisot’s gender and social standing. In the 1800s, boys were trained to take on roles of leadership and power, and girls were trained to be housewives and mothers. Girls were only allowed the opportunity to partake in “gentle accomplishments in those arts deemed suitable, such as needlework, watercolour, and singing-les art des femmes.”[4] Because it was within the realm of gentle accomplishment or amateur accomplishment, Morisot could participate in watercolour and oil painting.

Berthe Morisot’s career truly started with and was bolstered by her family. Her mother encouraged her first lessons in painting with her sister Edma, and when Berthe’s second teacher Guichard discovered their talent, he was quoted as asking Mme. Morisot, fearfully, whether she had given careful thought to the matter and “Considering the character of your daughters, my teachings will not endow them with minor drawing room accomplishments; they will become painters. Do you realize what this means? In the upper-class milieu to which you belong, this will be revolutionary, I might almost say catastrophic,”[5] This is because, as mentioned earlier, “accomplishments” were female tradition, they were appropriate for a young lady…however becoming a professional painter was not it was seen as overtly masculine[6]. Despite these fears, her mother “declared herself ready to face these chimerical dangers”[7] Her father was not far behind in his support, in 1864 he built his daughters a studio in the back garden of their home.[8]

With all of the support of her family, Berthe Morisot was able to advance in her skills and pursue a career that was not natural for a woman in the 1800s. Still, Morisot would never be able to officially enter the real realm of a painter, at least not in the same way that her male counterparts could. Morisot was not allowed to go to the city unchaperoned or to visit the spaces her male colleagues shared, like the Cafe Guerbois or Nouvelle Athenes[9] and their studios, where lively debates on the arts took place. In 1846 poet Charles Baudelaire put out a call for artists to paint in a more modern way.[10] Those in the Impressionist movement responded to his call; however, Baudelaire’s description of the modern artist was clearly male. Someone who was in charge of their own life, morality and money and had the ability to go out and experience the urban city on their own whim with a commanding presence – very masculine.[11] Women artists were unable to go to the city on their own, it was forbidden, and they couldn’t partake in the “cafes-concerts, dance halls, and street life”[12]Morisot knew she couldn’t experience life in this way, it wasn’t in her ability, for her expressing modernity had to look different. Men like Edouard Manet, Edgar Degas and Pierre-Auguste Renoir had their roles as modern male artists; they could go to the “racetrack, dance halls, cafe concerts, masked balls, bars, the Opera, and the holiday activities”[13] Subject matter and themes like bars, nudity, alcohol and smoking, among others were seen as masculine and off limits to women artists. For Morisot, her view of modern life had to be shared through her experiences, as a woman, in the domestic home, with friends and family in Passy.

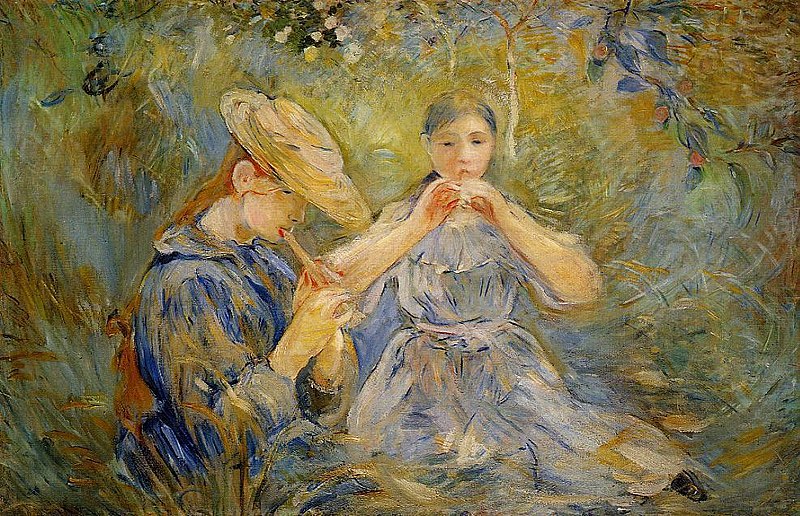

Because it had to be, Morisot’s “world” became her life in Passy, France. The world of women in Passy, France (the suburbia) was separate from the world of men in the city. The suburbs were Morisot’s constant muse and became the overarching subject of all her art. She ushered viewers into the very private personal life of her home, allowing them to experience and explore the secret life of women and children in their day-to-day. Her mother, sisters, daughter, nieces, cousins and friends all became, at one point, models and subjects of her pieces. Even her husband was a model for her, something that was unique as the male Impressionists painted their wives, so there were not many images of fathers in family settings. The idea of the women’s world being separate from the men’s world was something that Morisot explored in her artwork. It is said that the separation was deliberate and empowering, given the freedom women had within their own sphere of the suburbs.[14]

Critics often reviewed Morisot’s art in direct relationship to her femininity and the fact that she was a woman. Even when being positively admired, reviews often contended that Morisot’s work was amazing, not because of hard work, but because by her very nature, she was bound to create the exact style, composition, attention to detail, and use of colour that she delivered.[15] Her art was almost always described in feminine qualities and attributes, with examples such as delicate brushstrokes, subtlety, clarity of colour, grace, elegance and feminine charm being used.[16] It was thought that women could only merely copy what they saw, and that was why Impressionism was such a great vehicle for women to express themselves because it was simply copying their day-to-day experiences.[17] It was thought that women had an inability to have original ideas, as stated by S.C de Soisson “One can understand that women have no originality of thought and that literature and music have no feminine character”[18]

Regular meetings held in the homes of the haut bourgeois groups “served as a bridge between two worlds generally conceived of at this date as being entirely separate, the “women” world of the home and the “mans” world of business and commerce”[19] When she was first starting out under Guichard, copying paintings in the Louvre, she connected with many artists whom she would form lifelong friendships with. The greatest of which was Edouard Manet. Her mother would have regular dinners that included visitors like Camille Corot, The Manet family, Degas, Alfred Stevens, Pierre Puvis de Chavennes, James Tissot, Henri Fantin-Latour, Carolus-Duran and the future minister Jules Ferry. Later after 1884, Morisot and her husband would host dinners that brought together Mallarme, Renoir, Monet, and Degas, among others.[20] She was able to build relationships with fellow artists and maintain connections with them over the years and was highly respected by these peers and mentors. Her mother’s and her use of dinner parties to stay connected was an incredibly intelligent move.

Morisot was a founding member of the “Impressionist Group,” a group of artists that included but was not limited to, Degas, Manet, Renoir and Mary Cassatt. When it was founded on December 27th, 1873, she was one of its core members. She was committed to both the new exhibition and the style of art that the group approached.[21] She was not moved by any negative criticism to stop participation. She was even present at meetings held to organize the exhibitions and discuss policy (though more informal meetings she could not participate in because it would have been unbecoming).[22] The Impressionist Group and the Exhibitions they put on for 12 years were meant to push back at the Salon and break through limitations in art.

Morisot has had a lasting influence on the art world. She has aided in our understanding of the 1800s and what it meant to be a woman in the suburbs of Paris during that time. Her work as an Impressionist in the Impressionism movement has inspired and influenced many people and, since her time, paved the way for more art movements such as Post-Impressionism, Neo-Impressionism, Fauvism, Cubism, and Abstract Expressionism, to name a few. Her career and life were unique. Morisot was a painter and a mother, each of these identities never made the other impossible in her life.

Theodore Duret wrote Morisot “constantly found that her status as a society woman overshadowed her artistry…She knew she was the equal of any painter and quietly suffered from being treated as an amateur”[23] Morisot presents a fascinating case. She embodied the essence of a bourgeois woman, taking pride in her position in society. Simultaneously, she cherished her roles as a devoted mother and wife and her role as a painter. In her collaboration with the Impressionists, Morisot adeptly leveraged her unique position and perspective to craft a substantial body of work. This body of work not only attests to her unwavering determination and resilience in navigating her circumstances to her advantage but also mirrors the prevalent, albeit sometimes stereotypical, portrayal of femininity in her era.[24] Were it not for her experiences of womanhood in the 1800s, she would not have produced the same kind of art.

Bibliography

Adler, Kathleen, and Tamar Garb. Berthe Morisot. Oxford: Phaidon Press Limited, 1987.

Anderson, Jill. “The Meaning beyond the Dress: Alterity and Economy of Desire in Mallarmé’s Berthe Morisot.” French Studies 60, no.1 (2006): 33–48. doi:10.1093/fs/kni286.

Edelstein, T.J, ed. Perspectives on Morisot. New York: Hudson Hills Press, Inc, 1990.

Hyslop, Francis E. “Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt.” College Art Journal 13, no.3 (1954): 179–84. https://doi.org/10.2307/772550.

Kang, Cindy, Marianne Mathieu, Nicole Myers, Sylvie Patry, and Bill Scott. Berthe Morisot Woman Impressionist. New York: Rizzoli International Publication, Inc, 2018.

Kearns, James. “Mallarme and Morisot in 1896.” Australian Journal of French Studies 31, no.1 (1994): 71-82. DOI: 10.3828/AJFS.31.1.71.

Ravalico, Lauren. “Berthe Morisot’s Subversive Objectification of Women.” Women in French Studies 29, no.1 (2021): 12-31. https://doi.org/10.1353/wfs.2021.0001.

Ringelberg, Kirstin. “No Room of Ones Own: Mary Fairchild Macmonnies Low, Berthe Morisot, and The Awakening.” Prospects 28, no.1 (2004):127-154. DOI: 10.1017/s0361233300001459.

R. M. F. “A Painting by Berthe Morisot.” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago (1907-1951) 18, no. 4 (1924): 50–51. https://doi.org/10.2307/4116226.

Rouart, Denis, ed. The Correspondence of Berthe Morisot with Her Family and Her Friends. London & Bradford: Percy Lund, Humphries and CO. LTD, 1959.

[1] Denis Rouart, ed, The Correspondence of Berthe Morisot with her family and her friends (London & Bradford: Percy Lund, Humphries and CO. LTD, 1959), 1-2.

[2] Denis Rouart, ed, The Correspondence of Berthe Morisot with her family and her friends (London & Bradford: Percy Lund, Humphries and CO. LTD, 1959), 11.

[3] Kathleen Adler and Tamar Garb, Berthe Morisot (Oxford: Phaidon Press Limited,1987), 11.

[4] Adler and Garb, Berthe Morisot, 10.

[5] Rouart, The Correspondence of Berthe Morisot, 14.

[6] Adler and Garb, Berthe Morisot, 97.

[7] Rouart, 14.

[8] Suzanne Glover Lindsay, Berthe Morisot: Nineteenth-Century Woman as Professional, quoted in Edelstein, T.J, ed, Perspectives on Morisot (New York: Hudson Hills Press, Inc, 1990), 79.

[9] Beatrice Farwell, Manet, Morisot and Propriety, quoted in Edelstein, T.J, ed, Perspectives on Morisot (New York: Hudson Hills Press, Inc, 1990), 46.

[10] Adler and Garb, Berthe Morisot, 80.

[11] Adler and Garb, Berthe Morisot, 80.

[12] Adler and Garb, Berthe Morisot, 80.

[13] Anne Schirrmeister, La Derniere Mode: Berthe Morisot and Costume, quoted in Edelstein, T.J, ed, Perspectives on Morisot (New York: Hudson Hills Press, Inc, 1990), 103.

[14] Kathleen Adler, The spaces of everyday life: Berthe Morisot and Passy, quoted in Edelstein, T.J, ed, Perspectives on Morisot (New York: Hudson Hills Press, Inc, 1990), 35.

[15] Tamar Garb, Berthe Morisot and the Feminizing of Impressionism, quoted in Edelstein, T.J, ed, Perspectives on Morisot (New York: Hudson Hills Press, Inc, 1990), 61.

[16] Garb, Berthe Morisot and the Feminizing of Impressionism, quoted in Edelstein, T.J, ed, Perspectives on Morisot, 58.

[17] Garb, Berthe Morisot and the Feminizing of Impressionism, quoted in Edelstein, T.J, ed, Perspectives on Morisot.

[18] S.C de Soisson, [Charles Emmanuel de Savoie, comte de Carignan], Boston Artists: A Parisian Critic’s Notes (Boston,1894),76, quoted in Edelstein, T.J, ed. Perspectives on Morisot (New York, 1990),58.

[19] Adler and Garb, Berthe Morisot, 29.

[20] Sylvie Patry, Berthe Morisot: Stimulating Ambiguities, quoted in Berthe Morisot Woman Impressionist (New York: Rizzoli International Publication, Inc, 2018), 24.

[21] Adler and Garb, Berthe Morisot, 52.

[22] Adler and Garb, Berthe Morisot, 32.

[23] Patry, Berthe Morisot: Stimulating Ambiguities, quoted in Berthe Morisot Woman Impressionist, 15.

[24] Adler and Garb, Berthe Morisot, 102.