1 Chapter 1 – Rococo through Neo-Classicism

France

Megan Bylsma

By the end of this chapter you will be able to:

- define the terms ‘Rococo’, ‘Enlightenment’, and ‘Classicism.’

- describe the Rococo style and its purpose.

- identify the philosophies of the Enlightenment.

- explain the historical basis of Neo-Classicism.

- describe the identifying characteristics of Neo-Classicism.

Chapter opening in audio:

The Rococo

It is easy to look at the Rococo era as nothing more than silly, insipid rich people celebrating their wealth in the most opulent ways. Which, in some part, it really was. However, there was also more going on with the Rococo then just “Wheee! We’re rich! And lascivious!” But not by much.

It is difficult to really understand the reality of the Rococo Era by just looking at pictures of its art. The Rococo was a full sensory experience, from how the fabric you were wearing felt and the sound it made when it moved, to the food you ate, the company you kept, the topics you talked about, the people you flirted with, the music that was played (either by you or someone else) and the way the rooms were decorated while you talked and played. This was an expensive, time consuming, experiential aesthetic lifestyle. And it was a lifestyle and aesthetic for the rich. (As most aesthetic-based lifestyles are.)

The Rococo (also spelled ‘Roccoco’) period could not have come about were it not for the earlier years of the 1700s. The absolute power of the King of France had kept the aristocracy trapped at the Palace of Versailles, under his watchful eye, and away from their city homes in Paris. After his death, the aristocracy flooded back to Paris. Happy to be free of the palace, feeling resentful for the amount of control exercised over their lives, and moving back into apartments in serious need of a decorating update due to their long absence. With all the money and time they could desire at their disposal, they indulged in creating the most comfortable, exciting, and luscious surroundings possible.

The aristocracy had enormous political power as well as enormous wealth. Many chose leisure as a pursuit and became involved themselves in romantic intrigues. Indeed, they created a culture of luxury and excess that formed a stark contrast to the lives of most people in France. The aristocracy—only a small percentage of the population of France—owned over 90% of its wealth. This disparity in wealth fuelled growing national discontent.”

Fragonard’s The Swing and Sexual Mores

The story in Fragonard’s The Swing is one of flirtation, concupiscence, and infidelity; but in this painting there is no judgement or call to resistance. Martial infidelity was a common, cultural occurrence among French nobility at this time. As early as the 1500s the king of France had a mistress as part of his court. The title given to the woman in this position was maîtresse-en-titre and this semi-official position came with power and apartments at the palace (whereas a petite maîtresse was an unacknowledged, completely unofficial mistress to the king). Therefore it is not strange that by the 1700s it was expected that every married man of means would keep at least one mistress. The keeping of mistresses was merely part of the way of life for the upper classes in France at this time – all the wealthy men had them and all the women knew about them. Paintings, like The Swing, that celebrated, normalized, and made light of the moral decadence of the ruling classes added fuel to the fire of the Enlightenment. Those that called for social and moral reforms used examples of art like this to call society to a searching for their moral fiber and to value heroism and duty over self-indulgence and avarice.

Rococo architecture and interior design were as indulgent and over the top as the paintings of the time. This salon was created for a new, young, wife in a city mansion located at 60 rue des Francs-Bourgeois, in Paris. The gilted and highly decorated interior highlighted here was not an unusual feature for Rococo interiors. Integrated wall paintings like those in the spaces between the window arches near the ceiling, were popular – as were silk wall coverings punctuated with easel paintings.

This integrated painting is a series of paintings in the alcoves in this room that relate the story of Eros and Psyche. Now remember that these paintings would be seen in either daylight, or more often, as this was a room for entertaining guests, by candlelight. Seen in microscopic singular detail, as is often the case with digital viewing in the 21st century, these paintings seem odd and over the top. But in situ, in the ambience of candlelight reflecting off of glass, mirrors and gold, it would have seemed quite in keeping with the tastes of the day. The selection of this story of Psyche on the alcoves is interesting because it is the love story of the human Psyche and the god Eros. In this story, Psyche is a beautiful human who, after a series of misadventures, is the object of the god Eros’ affections. Eros had been given the task of destroying Psyche, but instead he had fallen in love with her and knew that to keep their love a secrete from Aphrodite, Psyche must never see his face. However, she eventually sneaks a peek during the night and Eros immediately leaves her. After much sad seeking of her love, Psyche asks Aphrodite for help and is given dangerous tasks to complete. In the end, she is rescued by Eros, who asks Zeus to allow Psyche into the pantheon of gods and demi-gods so that their love is no longer forbidden and to appease the anger of Aphrodite. When Psyche is elevated to Mount Olympus, she and Eros live happily ever after. This story is considered to be one of the first and few fairytale like stories from Greek myth, but it has an interesting moral that can be argued from the story. As Petra ten-Doesschate Chu explains in her book Nineteenth-century European Art, to use the story of Psyche and Eros seems like a lovely love story in keeping with the flirtatious expectations of the Rococo. Yet, this particular love story may have also seen as a story about questioning authority and rebelling against the absolute rule (as the nobles had just been released from Versaille by the death of King Louis the XIV) and bending the will of the ruler to that of the ruled. Just as the moral of the story of Psyche and Eros is deeply hidden and really only a small factor in the overall message of the story so the questioning of authority was only a glimmer of a growing idea in the minds of the French people at this time.

Even the smallest of glimmering flames can be fanned into a raging fire, though. Fed up with the self-indulgent and self-congratulating celebration of the bourgeoisie, the seeds of the Enlightenment were planted.

The Enlightenment

The fact that one section ended and another began in this resource would make it seem like the Rococo era ended and was succeeded dramatically by the Age of Reason, but in reality the Rococo and the Enlightenment sort of melded one into the other. In the fancy, rich interiors of Rococo extravagance there were dinner parties with witty, rich, and intelligent people having conversations and questioning authority. As these conversations grew more strident and the thoughts become more clearly formed people like the philosophers of the eighteenth century – Voltaire, Diderot, d’Alembert – came to believe that reason, logic, and duty were the only things that would save humanity from its own decadence.

Madame de Pompadour

This portrait of Madame de Pompadour – the king’s leading mistress – shows her with books, papers, and music – a nod to her intelligence, ‘good taste’ and patronly generosity. Jeanne Antoinette Poisson, Marquise of Pompadour – aka Madame de Pompadour – used her position in the royal court to shrewdly wield her influence for the arts and other intellectual endeavours. Maurice Quentin de La Tour’s portrait of Madame de Pompadour surrounded by books, including a copy of Encyclopédie, was an acknowledgement of her role in the intellectual undertaking of the first ‘Encyclopédie’, or what we now refer to, in English, as an Encyclopedia. It was to be a compendium of illustrated knowledge that encompassed everything known to the intellectuals at the time – from horse tack to liturgical seasons. Madame de Pompadour became its protector as rival intellectuals from the French Academy and high ranking members of the Catholic Church, including Archbishop of Paris Christophe de Beaumont and Pope Clement XIII, were quite against the undertaking as some of the articles in it were quite provoking.[1] Due to Madame de Pompadour’s diplomatic interventions the Encyclopédie was completed and published (although it was placed on the list of banned books by Pope Clement).

Jeanne Antoinette Poisson, Marquise of Pompadour is an excellent example of the dual existence of Rococo excess and Enlightenment intellect. Madame de Pompadour was the official mistress to the king – a role she received by calculated and direct flirtation with him. She attended salons where food, talk, music, and wit flowed. She hosted grand parties and redecorated her many dwellings frequently and opulently. She held even greater power in the king’s court once she received the title of lady-in-waiting to the Queen of France. She lavished money and favours on those she deemed worthy; she removed those that disappointed her from their positions. Her influence was felt especially in the arts and other realms of intellectual pursuit. She was an also an artist after a fashion, although some debate whether her work was really her own, or a collaboration with the artists she championed.[2] She learned how to engrave gemstones from the king’s own engraver, Jacques Guay and learned printmaking from François Boucher, a member of the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture.[3] Boucher created a series of drawings of pieces by Guay that Madame de Pompdour engraved and printed.

The Academy, the Salon, and the Critic in audio:

The Academy, the Salon, & the Critic

This is an artist’s rendering of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture’s Salon of 1765 – exhibitions like this were extremely important to the art world. The public came in crowds to see the new art and artists’ careers were dependent on being accepted into the Salon shows. However, this also had a stifling effect on creativity as the Salon juries and the Academy controlled what kind of art and subject were accepted. If a style or subject was not popular with the Academy it would either be denied entry to the Salon, or it would be hung in a place where it would be easily overlooked. The term ‘Salon hang’ comes from the way art was arranged at these shows; because the shows were popular, art was hung side-by-side and next to each other, nearly floor to ceiling. The spaces not taken up by paintings of all sizes were filled with sculptures, and by contemporary standards the final product was a very cluttered and overwhelming display space where things could be easily missed by a viewer enveloped in a crowd.

The Academy controlled what art was accepted and where art pieces were hung – if the artist was a watercolour artist (watercolour was considered inferior and not good enough for finished works of art or was left to hobbyists and female artists) who managed to get into the Salon with a smaller sized piece of work, the work was likely to be ‘skied’ or hung up at the top where the huge historical genre paintings were hung – so no one saw it anyway. Ironically, much of the documentation of the Academy Salons was in the form of watercolour works, like this piece by Gabriel-Jacques de Saint-Aubin.

Eventually, the Academy Salon shows gave rise to the creation of the art critic. Completely accepted as a form of journalism, art critique was common in the journals, pamphlets, and newspapers from the mid-18th-century on. Almost immediately, art critics began to lament the state of art being created (somethings never do change). These critics condemned the decadence and sensual self-indulgence that was evident in the artwork. Of course, the artists hated the critics for daring to critique their work. Artists at that point were not used to be criticized because until the emergence of the art critic the fact that their art had been chosen to be showcased in an Academy exhibition proved that their art was part of unquestionable and unchallenged strata of creative work. To question the value, message, or technique of the art in the Academy exhibition was like critiquing the Academy! The Academy was formed by the king and run by aristocratic members of society, therefore questioning the art they approved was like questioning the king himself (in the minds of those who managed the Academy and its artists). Artists who had had the fortune of being sheltered within the Academy shows had only had to deal with critique and dramatic snobbery from withing the cultural structure of the Academy itself. The outside judgement of the critic-in-the-press was an unwelcome source of insubordinate antagonism. Thus began a long and complicated relationship between the established, main stream controller of art (the Academy), the artist, and the critic.

One particularly hated critic was Étienne La Font de Saint-Yenne. He was aghast at the level of decay and self-appreciation in the fine art and wrote works that called artists to abandon the frivolous, erotic themes of the Rococo art market and pursue themes of nobility and calm grandeur. He challenged artists to put away their sensuous colours, self-congratulating virtuoso brush work, and arousing asymmetrical compositions, and to find inspiration in Classical Greek and Roman art. La Font de Saint-Yenne felt that it was the right and duty of all intellectuals to challenge decadence when they saw it and he was not popular with the artists that he wrote about. Because the relationship between art critic and artist was very new at this time, many artists felt that a writer had no right to critique or judge visual arts in anyway. Judging the artist that had been accepted into an Academy Salon was akin to criticizing the Royal Academy – one of the king’s appointed power-brokers of cultural influence – and the French art world found the change to be a difficult adjustment.

Values of the Enlightenment

Denis Diderot, a philosopher and one of the editors of the Encyclopédie, took up the cry for artists to embrace noble, edifying, and intellectual sentiment based themes as well. Diderot admired works like Jean-Baptiste Greuze’s Filial Piety, for its reality and honour and sense of duty. Diderot praised Greuze’s work for showing non-upper class people living real, flawed lives with a noble sense of endurance. In this piece, the patriarch of the family commands attention and reverence from all, including the family pet, even from his sick bed and all members of the family respect and care for him. This is an image that is neither dramatic, nor sensual. It showcases and celebrates the calm dignity and noble service of respectful and dutiful family.

Which isn’t to say that Greuze didn’t have his own collection of nearly pornographic Rococo paintings and portraits, but by this time his work was frequently championing the same things that Diderot’s writing valued – virtuous examples and genuine sentiment mixed into contemporary realities.

The philosophers of the Enlightenment devised a social antidote to the ills of the Rococo. They felt moral reform and a return to the what they perceived were the values of the ancient Greeks and Romans were the only hope. The main values of the Enlightenment can be generalized as follows:

- nobility (noble action and attitude, not noble birth)

- calm grandeur

- edification (the instruction or improvement of a person morally or intellectually)

- virtuous character

- genuine sentiment

- intellectual development

- reality

- honour

- duty

However, the aristocracy, who so liked their naughty pictures were also buying these noble paintings and supporting this change in the arts. It is clear that Rococo sensibilities weren’t killed off suddenly as Enlightened ideals took over. Instead, the fashions simply co-existed with one another until one became more popular and sparked an initiative for drastic change.

And so the Enlightenment gradually came to be.

The Classical Paradigm in audio:

The Classical Paradigm

The art that is often seen as the epitome of the philosophies of the Enlightenment actually owes just as much to the ideas of the Classical Paradigm.

Art in the mid-1700s, as seen in the Rococo style, was suffering from a case of death-by-excess, or decadence. It was fluffy and frilly and self-serving and some people felt that it was showing how society at the time was the same. The Enlightenment called for noble, edifying art that could repair the moral fabric of the nation. But this also meant looking for new role-models in art aesthetics. Looking to Baroque and Rococo artists for a guide would only lead to more cotton candy lack-of-substance, looking to Michelangelo or the Renaissance artists would not lead to purity of intention or virtuousness since they also came from a flawed time and the great artists of the Renaissance received their inspiration from the Greeks. Scholars began to argue that the pinnacle of western society was age of the Greeks and thus the art of the 1700s should look to Homer, Plato and the Greek artists for pure and culturally untainted inspiration.

The literary work of Johann Joachim Winckelmann – Reflections on the Imitation of Greek Works in Painting and Sculpture, 1756 – called to imitate what was thought as a nobler, healthier and more fulfilling time. Winckelmann was one of the leading scholars at the time arguing this was the right way to look at reviving morality in culture.

This new kind of Classicism (Neo-Classicism) was more than just looking back to Grecian ideals. It was about finding ideals, purified of every imperfection – which while the Greeks also looked for what they called the ‘ideal’, was a different kind of ideal. When ancient the ancient Greeks looked to create an ideal form they were were looking to return to the ideal generic thing that was created at the beginning of the world; understanding that the first tree, animals, and humans created were the perfect and ideal specimen of each thing as considered ideal for their role by the gods. Therefore, if an ancient Greek artist found they had re-created perfection they could simply keep copying that as a form because there would never be a better version. In Grecian times, Polykleitos’ Spear Bearer, was considered perfectly ideal or ‘canon,’ and was therefore a rule of form that all others should follow. However, an artist couldn’t just create a single perfect figure and use it in all situations. Each ideal was home to its own ideals and narrative. For example, Polykleitos’ figure would have been a perfect athlete, a perfect young male (but not youth), and a perfect warrior, but the figure could never have been used to relay ideas of wisdom, age, or femininity. For those ideals a different ideal form was required. To the French in the 1700s the idea of ‘ideal’ didn’t have the same connotations of being related to the divine original copy of creation. It was more closely related to our contemporary understanding of ideal – something that is perfect, and un-improvable. However, the French scholars did feel that a Greek ideal would be closest to a cultural ideal of intelligence, strong character, and civic duty.

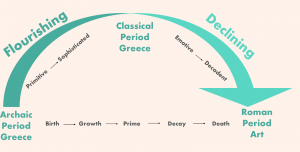

Pompeii and Herculaneum were re-discovered around 1599, while the first archaeological excavations began in 1764. Winckelmann was one of the scholars heavily influenced by this discovery, and he, as most other scholars, was sorely disappointed when he realized that the murals they found at Pompeii and Herculaneum did not live up to the preconceived ideas of what Greco-Roman art must have been. At Pompeii and Herculaneum the art varied from technically perfect to crudely rendered with subject matter that ran from the benign to the scandalous. Much of what was found there did not reflect a society that was perfect, healthy, and untainted by the vagaries of moral decay. In reaction to this discovery, Winckelmann hypothesized a developmental model for societies that has been applied to Greek and Roman art and culture ever since. His theory was that art in Greece and Rome must have had a life-cycle like that of a living creature; a birth, flourishing, prime, decay, and death arch. He explained, based on this theory, that the Classical Greek period was the high point. It had a primitive kind of learning period at the start of its life that flourished and grew into a high middle point that eventually decayed and grew stagnant and self-indulgent with the Roman period that built on the weakened ruins of the previous society.

This model continues to be the ‘canon’ of art history as it continues to be taught into the 21st century. Written in 1764, The History of Ancient Art put forward that idea and it has stuck to this day. It is challenging, though not impossible, to find any scholarly theories of the evolution of Greek and Roman art and culture that is not based on the model of a rudimentary beginning, perfected middle and over-indulgent end. However, this is an area that may require intense scrutiny as contemporary scholars have realized that how the art of the Greeks and Romans were viewed in the 1700s is not a representation of how the Greeks and Romans viewed their own cultural output.

When Winckelmann and his associates saw the marbles of the ancient Greeks and Romans, they saw them in their weathered and unpreserved states; weathered down to their raw marble foundations. The scholars of the 1700s accepted these sculptures as pieces that would have been presented in their raw white form because they were familiar with sculptures from the Renaissance, which were revered for their pristine white marble surfaces.

The sculptors of the Renaissance had also been influenced by the white Greek and Roman sculptures they had seen. The reality was that a white marble sculpture was simply a myth told by the harsh realities of time. Originally, ancient Greek sculptures were painted in bright colours and presented with an aesthetic that would have made the Neo-Classicists (and continues to make some present day people) quite uncomfortable.

This makes it clear that the foundations of Neo-Classicism were built on misinformed judgments regarding ancient cultures. However, the philosophers and scholars of 1700 France felt that change was needed in their society and so they looked back to a culture they believed to be better than their own. This combination of looking back to the ‘ideal’ era to find the ‘ideal’ way of communicating more edifying ideals and noble character gave birth to what we know as Neo-Classicism. However, the most famous works of art of the New Classical Era or Neo-Classical are also shown as examples of the Enlightenment because they really were doing double duty. Yet, this doesn’t mean that every painting of the Enlightenment was a Neo-Classicist work. Neo-Classical works were only ones that showed Greco-Roman themes and stories as a way of relaying a narrative of Enlightenment values, while Enlightenment works showed the values of the Enlightenment through a many narrative and aesthetic means.

Neo-Classicism in audio:

Neo-Classicism

Jacques-Louis David was one of the first, and now most famous, artists to combine the classical ideal of Neo-Classicism with the high ideals of the Enlightenment. Works like Oath of the Horatii show duty being chosen over emotion and nobility of character triumphing over self-fulfillment.

This painting showcases the moment when the sons of the Horatii family pledge honour and allegiance before engaging in a bloody battle. In the story of the Horatii of Rome versus the Curaitii of Alba there are much more dramatic and exciting moments than is shown here, but David chose to depict this moment of calm logic and sense of civic duty triumphing over emotion and self-preservation. The short version of story goes like this:

It is a story set in early Roman history. There is a border dispute between Alba and Rome. Rather than having a war with great cost to both sides, this dispute was solved by a duel between three men from Alba and three men from Rome – the finest swordsmen of each city-state. The three brothers from the Roman Horatii family were selected to fight the three brothers from the Alban Curiatii family. However, Sabina (the woman in blue and gold in the painting) – a Curiatii sister – was married to one of the Horatii brothers, while Camilla (the woman in white) – a Horatii sister – was engaged to one of the Curiatii boys. Either way this story was never going to have a happy ending for the women. In David’s painting the men with their strong silhouetting against the darkness of the background, their straight lines, and flexed muscles show the strength of resolve and the calm grandeur of noble sacrifice. However, the women, depicted in curving shapes, crumpled in grief, and trying to shield the children from the reality of death are shown as the character foil of the weakness of emotion, self-service, and inability to sacrifice for the reality of the circumstances.

(To finish the story: The Romans won the duel but only one Horatii brother came back. Camilla cursed her brother for the death of her fiancé and he flew into a rage and killed her. The end.)

Jacques-Louis David’s The Death of Socrates is often talked about as a prophesy of the coming French Revolution. One where Socrates is dying for an ideal of society that was perceived of as a threat by those in authority and this image is an allegory of those sacrifices coming in just 2 years. However, that isn’t how it would have been seen at the time and David could never have predicted where his country would have gone over the course of the decade. Here Socrates, calmly the embodiment of the eternal soul, is reminding his followers of the immortality of the soul while his followers embody the physical side of death with their fear. David chose to recreate this scene by departing from the historical record of this event and creating a scene that fit his ideals more closely. Despite that, this piece, along with the Oath of the Horatii, is considered part of the quintessential Neo-Classical genre.

Self-Reflection Questions 1.1 & 1.2

Consider the following questions:

- Do you think the contemporary world that we live in now is experiencing something like France during the Rococo/Enlightenment transition?

Or do you feel there is no correlation between the societal attitudes in the 1700s in France and the societal attitudes of today? - Do you think that the proliferation of ‘Prepper/Back-to-the-land’ groups and knowledge-sharing, ‘Before Technology’ nostalgia, and ‘Back In The Day’ stories are a sign of a kind of rebellion against a Rococo-esque self indulgence in our society?

Or do you find that the society we live in is not relatable to the ideas of the 1700s?

No matter which opinion you have, how would you debate your position with someone who disagreed?

- Évelyne Lever, Madame de Pompadour: A Life, translated by Catherine Temerson (New York: St. Martin's Press, 2003), 176. ↵

- Melissa Hyde, "The "Makeup" of the Marquise: Boucher's Portrait of Pompadour at Her Toilette," The Art Bulletin, 82 no. 3 (2000): 453–475. doi:10.2307/3051397. ↵

- Fletcher William Younger, Bookbinding in England and France, (Moscow: Рипол Классик, 1897), 70.; Jean Adhemar, Graphic Art of the 18th Century, (London: Thames and Hudson, 1964), 43, 106, 108, 113. ↵