20 Chapter 9 – Marie Bracquemond

Impressionism

Paige Ekdahl

Audio recording of the full chapter can be found here:

If you were to do some digging into the inspirational and inspiring Impressionist art of the late 1800’s you would see names like Mary Cassatt, or Claude Monet, to name a few, but you would have to dig deep to find the name and history of a female Impressionist named Marie Bracquemond. Marie Bracquemond was awarded the title as one of les trois grande dames of Impressionism by art critic Gustave Geffroy in 1894.[1] Though she held this title and was acknowledged as being one of the main female Impressionists to break the trail for others to follow, Bracquemond is almost always missing from the history books. If she was a trailblazer for future female artists, then what are the factors contributing to this? Marie Bracquemond was an adept artist whose art was undervalued and criticized by many, including those that should have been supporting her ingenuity by allowing her to flourish as a female, Impressionist artist.

The arts were mainly male dominated during the late 1800’s which made it hard for women like Marie Bracquemond and the other “grande dames” of Impressionism, Mary Cassatt and Berthe Morisot, to become successful artists.[2] Art was renowned for its sophistication and the respect that an individual gained from its spectacle, especially after having a piece of one’s personal art admitted into the Salon by The Academy. Fortunately, in 1857, Marie Bracquemond’s hard work paid off as she submitted a piece of her art to the Salon and it was accepted.[3] Following this achievement, in 1860, she was taken under the wing of a talented and well respected artist, Jean-Ausguste-Dominique Ingres.[4] This is where Bracquemond began her endeavor upstream, against the current of the male dominated profession. As quoted by Bracquemond during her time under the instruction of Ingres,

The severity of M. Ingres frightened me, I tell you, because he doubted the courage and perseverance of a woman in the field of painting. He wished to impose limits. He would assign to them only the painting of flowers, of fruits, of still lifes, portraits and genre scenes.[5]

Female artists, like Marie Bracquemond, had to persevere through the misogyny that is ingrained in the artistic profession to prove their competence as professional, competent artists.

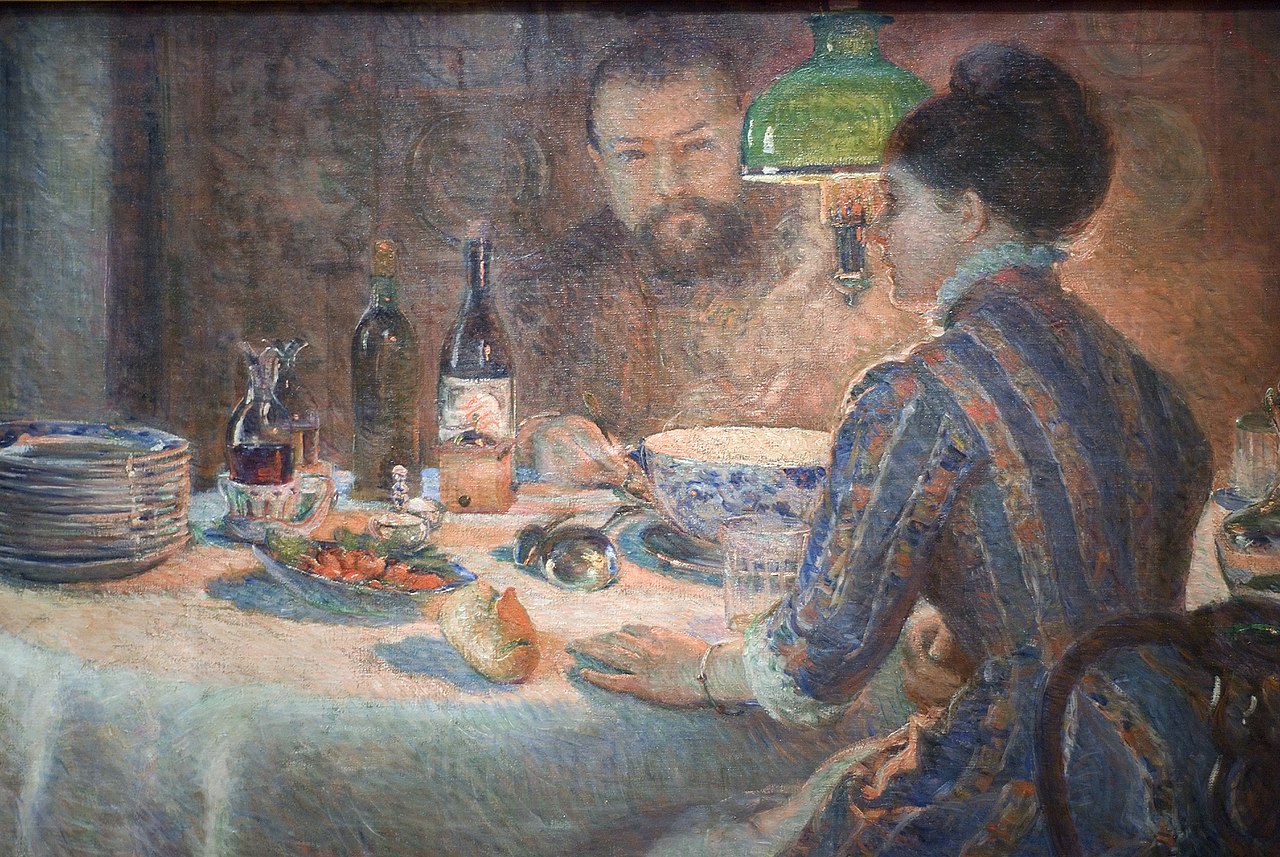

Marie Bracquemond had to conquer many obstacles throughout her artistic journey. One significant mountain Marie had to climb was her husband, Felix Bracquemond’s disapproval and jealousy of her success as an artist. Marie Bracquemond, formerly Marie Quivoron, was married to Felix Bracquemond in 1869 and they had one child, Pierre, in 1870.[6] In 1877, Marie admired the work of Monet and Renoir, which altered her view of the aesthetic that her art portrayed; she then chose to pursue down the path towards Impressionism.[7] Bracquemond said that “Impressionism had produced… not only a new, but a very useful way of looking at things” as though “all at once a window opens and the sun and air enter your house in torrents.”[8] Alternatively, Felix, an admired painter, ceramist and printmaker, hated his wife’s move away from medieval motifs and towards Impressionism; he deemed the Impressionist aesthetic as distasteful and actively sought to obliterate it.[9] Despite being continually degraded as an Impressionist artist by Felix, in 1880, Marie painted The Woman in White, which was an innovative Impressionist painting that utilized the sinuous aspect of a woman’s white dress with the delicate, flowing detail of colour surrounding her. This painting ignited Marie’s creations of other pieces in 1880 like, On the Terrace at Sevres, and Tea Time, and The Three Graces; all of these paintings exemplify the same assemblage of similarly aesthetically pleasing pieces.[10] Succeeding these exquisite paintings that Marie Bracquemond created in 1880, there is a gap of approximately five years, 1881-1886, where she did not produce any pieces of art at all.[11] Why was this? I believe the reason that there is a gap of five years is because Marie began to realize she was fighting a losing battle against Felix that she needed to take a step away from to gain some clarity about the direction she wished her life to go. Though he never outwardly admitted it, Felix’s antipathy regarding Marie’s Impressionist pieces influenced her success as an artist by hindering her public recognition and impeding on her complexion of artful style.[12]

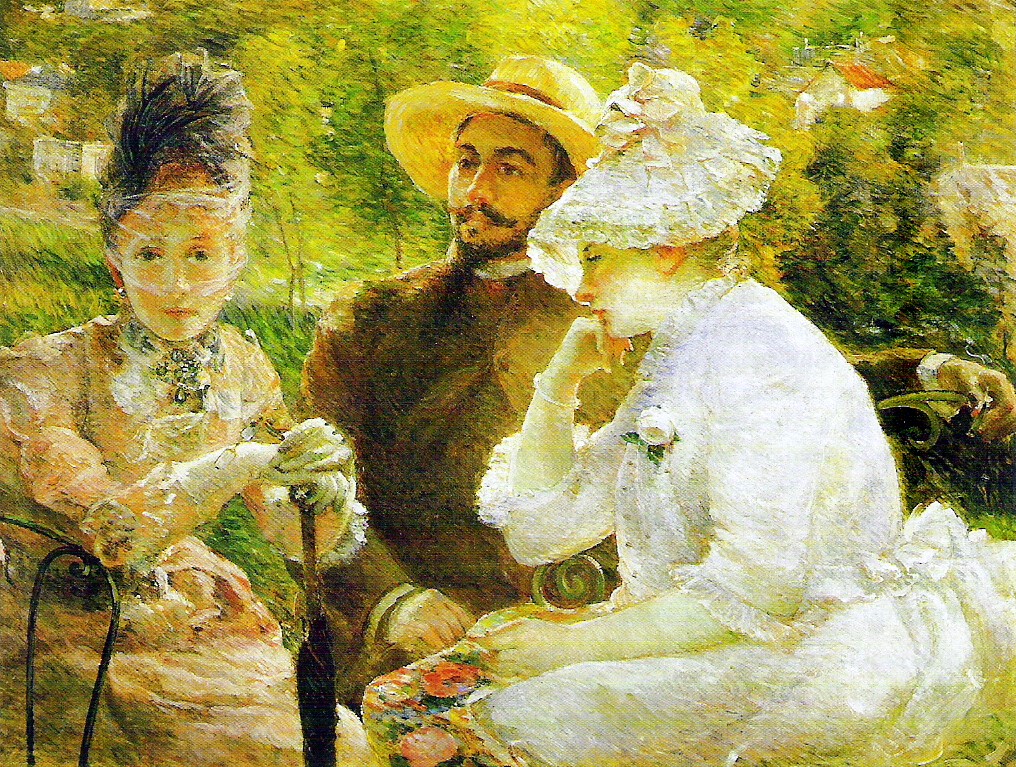

Eventually everything must come to an end and unfortunately, sometimes that end comes sooner than anticipated. Marie Bracquemond continued pursuing her artistic career by making more Impressionist paintings up until 1890 when she inevitably succumbed to Felix’s constant enmity towards her and the Impressionist path that she so eagerly wanted to see through.[13] Following 1890, Bracquemond only created small, private pieces including The Artist’s Son and Sister in the Garden of Sevres.[14] This painting shows the relationship between the colours by including the blues and reds, while having a detailed, yet contrasting background that plays on the darks and lights. Much like the painting The Woman in White, Bracquemond demonstrates her proficiency in portraying the beautiful details on the white dress on one of the figures; she adds flowing, yet subtly sharp details that accent the definition of the woman’s dress. Both figures are not facing forward, showing Bracquemond’s confidence in her ability to delineate the serenity felt by the man and woman outside savouring a beautiful day. Marie Bracquemond made a bold decision moving towards Impressionism when she did, especially with all of the factors that were urging her against it but, she had a true aptitude to express all that Impressionism is and she did so for as long as she could.

Marie Bracquemond had many factors that influenced her artistic success that ultimately ended her career: societal misogyny, a jealous husband and her role as a mother. All of these components slowly buried Bracquemond deeper and deeper into the art history books, typically only to be mentioned in the occurrence of her husband’s name. Should you dig deep enough to find information on her, you will learn how intuitive, inventive and incredible she was. Marie Bracquemond helped pave the way for many other female artists regardless of having been the least known out of the les trois grande dames of Impressionism.[15] Though she capitulated her art career to the pressures of her unrelenting husband and her constant effort of climbing the social ladder as a female artist, she did not end up where she had planned, but she did manage to make an impression as an Impressionist.

Bibliography

Avarvarei, Simona C. “Medusa as the story of Victorian feminine identity.” Journal of History Culture and Art Research 4, no. 3 (2015): 63-7. doi:10.7596/taksad.v4i3.480.

Bouillon, Jean-Paul, and Elizabeth Kane. “Marie Bracquemond.” Woman’s Art Journal 5, no. 2 (1984): 21-27. Accessed September 18, 2020. doi:10.2307/1357962.

College Art Association. “Some Things New Under the Sun.” Art Journal 35, no. 3 (1980): 205-6. Accessed September 18, 2020. doi:10.2307/776356.

Dwyer, Britta C. “Women Impressionists Berthe Morisot, Mary Cassatt, Eva Gonzales, Marie Bracquemond By Max Hollein (Ed.).” The Art Book 16, no. 2 (May 2009): 46–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8357.2009.01027_12.x.

Hutton, John. “Picking Fruit: Mary Cassatt’s “Modern Woman” and the Woman’s Building of 1893.” Journal of Feminist Studies 20, no. 2 (1994): 318-348. doi: 10.2307/3178155.

Myers, Nicole. “Women Artists in Nineteenth-Century France.” metmuseum.org, 2008. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/19wa/hd_19wa.htm

- 1 Bouillon, Jean-Paul, and Elizabeth Kane. "Marie Bracquemond." Woman's Art Journal 5, no. 2 (1984): 21. ↵

- Avarvarei, Simona C. “Medusa as the story of Victorian feminine identity.” Journal of History Culture and Art Research 4, no. 3 (2015): 65. ↵

- Bouillon and Kane, “Marie Bracquemond,” 22. ↵

- Myers, Nicole. “Women Artists in Nineteenth-Century France.” metmuseum.org, 2008. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/19wa/hd_19wa.htm ↵

- Myers, Nicole. “Women Artists in Nineteenth-Century France.” metmuseum.org, 2008. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/19wa/hd_19wa.htm ↵

- Bouillon and Kane, “Marie Bracquemond,” 22 ↵

- Bouillon and Kane, “Marie Bracquemond,” 22. ↵

- Hutton, John. “Picking Fruit: Mary Cassatt's "Modern Woman" and the Woman's Building of 1893.”Journal of Feminist Studies 20, no. 2 (1994): 337. ↵

- Bouillon and Kane, “Marie Bracquemond,” 22. ↵

- College Art Association. “Some Things New Under the Sun.” Art Journal 35, no. 3 (1980): 205; Bouillon, Jean-Paul, and Elizabeth Kane. "Marie Bracquemond." Woman's Art Journal 5, no. 2 (1984): 24-5 ↵

- Bouillon and Kane, “Marie Bracquemond,” 24. ↵

- Bouillon and Kane, “Marie Bracquemond,” 27 ↵

- Bouillon and Kane, “Marie Bracquemond,” 27 ↵

- Bouillon and Kane, “Marie Bracquemond,” 27 ↵

- Dwyer, Britta C. “Women Impressionists: Berthe Morisot, Mary Cassatt, Eva Gonzales, Marie Bracquemond.” Art Book 16, no. 2 (May 2009): 47. ↵