The Process of Communication

The Process of Communication

Communication is vital to organizations—it’s how we coordinate actions and achieve goals. It is defined in Webster’s dictionary as a process by which information is exchanged between individuals through a common system of symbols, signs, or behavior. Interpersonal communication allows employees at all levels of an organization to interact with others, secure desired results, request or extend assistance, and make use of and reinforce the formal design of the organization. These purposes serve not only the individuals involved but the larger goal of improving the quality of organizational effectiveness.

.

The Process of Communication

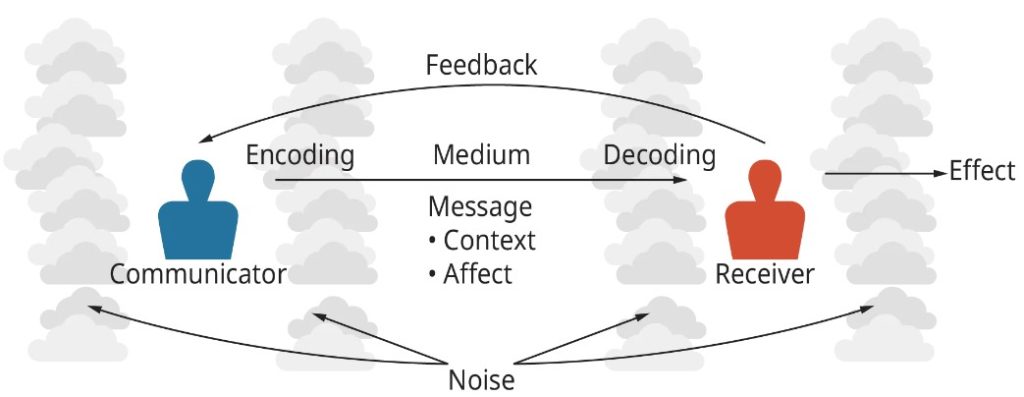

What does communication look like? When you think about communication in its simplest form, the process is quite linear. The model presented here is an oversimplification of what happens in communication, but this model will be useful in creating a diagram to be used to discuss the topic. The image below illustrates a simple communication episode where a communicator encodes a message and a receiver decodes the message.

| Let’s look at an example: |

|---|

| ~ A communicator, such as a boss, coworker, or customer, originates the message with a thought. For example, the boss’s thought could be: “Get more printer toner cartridges!”

~ The sender encodes the message, translating the idea into words. ~ The boss may communicate this thought by saying, “Hey you guys, let’s order more printer toner cartridges.” ~ The medium of this encoded message may be spoken words, written words, or signs. ~ The receiver is the person who receives the message. ~ The receiver decodes the message by assigning meaning to the words.

In this example, our receiver – let’s call him Bill – has a to-do list a mile long. “The boss must know how much work I already have,” the receiver thinks. Bill’s mind translates his boss’s message as, “Could you order some printer toner cartridges, in addition to everything else I asked you to do this week…if you can find the time?” The meaning and emotion placed on the message by Bill is referred to as noise.

|

Encoding and Decoding

Two important aspects of this model are encoding and decoding. Encoding is the process by which individuals initiating the communication translate their ideas into a systematic set of symbols (language), either written or spoken. Encoding is influenced by the sender’s previous experiences with the topic or issue, her emotional state at the time of the message, the importance of the message, and the people involved. Decoding is the process by which the recipient of the message interprets it. The receiver attaches meaning to the message and tries to uncover its underlying intent. Decoding is also influenced by the receiver’s previous experiences and frame of reference at the time of receiving the message.

Feedback

Several types of feedback can occur after a message is sent from the communicator to the receiver. Feedback can be viewed as the last step in completing a communication episode and may take several forms, such as a verbal response, a nod of the head, a response asking for more information, or no response at all. As with the initial message, the response also involves encoding, medium, and decoding.

Three basic types of feedback occur in communication>[1]. These are informational, corrective, and reinforcing. In informational feedback, the receiver provides non-evaluative information to the communicator. An example is the level of inventory at the end of the month. In corrective feedback, the receiver responds by challenging the original message. The receiver might respond that it is not their responsibility to monitor inventory. In reinforcing feedback, the receiver communicated that they have clearly received the message and its intentions. For instance, the grade that you receive on a term paper (either positive or negative) is reinforcing feedback on your term paper (your original communication).

Noise

The meaning that the receiver assigns may not be the meaning that the sender intended, because of factors such as noise. Noise is anything that interferes with or distorts the message being transformed. Noise can be external in the environment (such as distractions) or it can be within the receiver. For example, the receiver may be extremely nervous and unable to pay attention to the message. Noise can even occur within the sender: The sender may be unwilling to take the time to convey an accurate message, or the words that are chosen can be ambiguous and prone to misinterpretation.

.

Directions of Communication

Organizations communicate to ensure employees have the necessary information to do their jobs, feel engaged, and be productive. Communication travels within an organization in three different directions, and often the channels of communication are prescribed by the direction in which the communication is flowing. Let’s take a look at the three different directions and types of communication channels used.

Vertical Communication

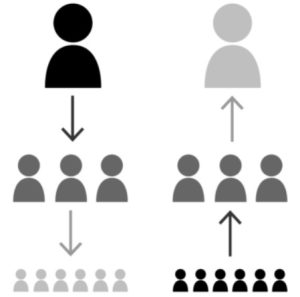

Vertical communication can be broken down into two categories: downward communication and upward communication.

Downward Communication

Downward communication is from the higher-ups of the organization to employees lower in the organizational hierarchy, in a downward direction. It might be a message from the CEO and CFO to all of their subordinates, their subordinates, and so on. It might be a sticky note on your desk from your manager. Anything that travels from a higher-ranking member or group of the organization to a lower-ranking individual is considered downward organizational communication.

.

Downward communication might be used to communicate new organizational strategies, highlight tasks that need to be completed, or they could even be a team meeting run by the manager of that team. Appropriate channels for these kinds of communication are verbal exchanges, minutes and agendas of meetings, memos, emails, and even Intranet news stories.

Upward Communication

Upward communication flows upward from one group to another that is on a higher level on the organizational hierarchy. Often, this type of communication provides feedback to organizational leaders about current problems, or even progress on goals.

It’s probably not surprising that “verbal exchanges” are less likely to be found as a common channel for this kind of communication. It’s certainly fairly common between managers and their direct subordinates, but less common between a line worker and the CEO. However, communication is facilitated between the front lines and senior leadership all the time. Channels for upward communication include not only a town hall forum where employees could air grievances, but also reports of financial information, project reports, and more. This kind of communication keeps managers informed about company progress and how employees feel, and it often provides managers with ideas for improvement.

Horizontal Communication

When communication takes place between people at the same level of the organization, like between two departments or between two peers, it’s called horizontal (or lateral) communication. Communication taking place between an organization and its vendors, suppliers, and clients can also be considered horizontal communication.

.

Even though vertical communication is very effective, horizontal communication is still needed and encouraged, because it saves time and can be more effective—imagine if you had to talk to your supervisor every time you wanted to check in with a coworker! Additionally, horizontal communication takes place even as vertical information is imparted: a directive from the senior team permeates through the organization, both by managers explaining the information to their subordinates and by all of those people discussing and sharing the information horizontally with their peers.

Not all organizations are set up to facilitate good horizontal communication, though. An organization with a rigid, bureaucratic structure—like a government organization—communicates everything based on the chain of command, and often horizontal communication is discouraged. Peer sharing is limited. Conversely, an organic organization—which features a loose structure and decentralized decision-making—would leverage and encourage horizontal communication.

Horizontal communication sounds like a very desirable feature in an organization and, used correctly, it is. Departments and people need to talk between themselves, cutting out the “middle-person” of upper management in order to get things done effectively. Unfortunately, horizontal communication can also undermine the effectiveness of downward communication, particularly when employees go around or above their superiors to get things done, or if managers find out after the fact that actions have been taken or decisions have been made without their knowledge.