Team Effectiveness

Team Effectiveness

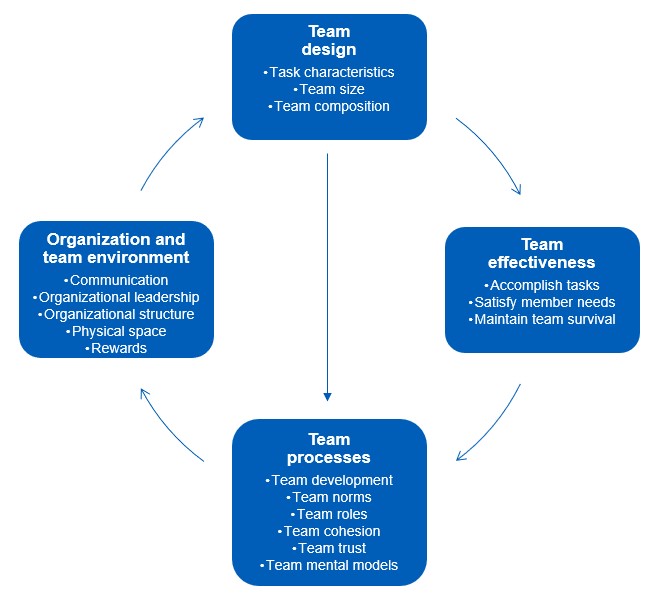

So, why are some teams effective while others fail? To answer this question, we first need to clarify the meaning of team effectiveness. A team is effective when it benefits the organization and its members and survives long enough to accomplish its mandate[15].

Designing an effective team means making decisions about team composition (who should be on the team), team size (the optimal number of people on the team), and team diversity (should team members be of similar backgrounds, such as all engineers, or of different backgrounds). Teams need to exist to serve some organizational purpose, therefore effectiveness is partly measured by the achievement of that objective. A team’s effectiveness also relies on the satisfaction and well-being of its members. Finally, the team members need to be motivated enough to remain together long enough to accomplish the assigned objective. Consider the Team Effectiveness Model below:

.

Who are the Best Individuals for the Team?

A key consideration when forming a team is to ensure that all the team members are qualified for the roles they will fill for the team. This process often entails understanding the knowledge, skills, and abilities (KSAs) of team members as well as the personality traits needed before starting the selection process[16]. When talking to potential team members, be sure to communicate the job requirements and norms of the team. To the degree that this is not possible, such as when already existing groups are utilized, think of ways to train the team members as much as possible to help ensure success. In addition to task knowledge, research has shown that individuals who understand the concepts such as conflict resolution, motivation, planning, and leadership, actually perform better in their jobs. This finding holds for a variety of jobs, including being an officer in the Royal Canadian Air Force, an employee at a pulp mill, or a team member at a box manufacturing plant[17].

.

How Large Should My Team Be?

Interestingly, research has shown that regardless of team size, the most active team member speaks 43% of the time. The difference is that the team member who participates the least in a 3-person team is still active 23% of the time versus only 3% in a 10-person team[18]. When deciding team size, a good rule of thumb is a size of two to 20 members. Research shows that groups with more than 20 members have less cooperation[19]. The majority of teams have 10 members or fewer, because the larger the team, the harder it is to coordinate and interact as a team.

.

With fewer individuals, team members are more able to work through differences and agree on a common plan of action. They have a clearer understanding of others’ roles and greater accountability to fulfill their roles (remember social loafing?). Some tasks, however, require larger team sizes because of the need for diverse skills or because of the complexity of the task. In those cases, the best solution is to create subteams in which one member from each subteam is a member of a larger coordinating team. The relationship between team size and performance seems to greatly depend on the level of task interdependence, with some studies finding larger teams outproducing smaller teams and other studies finding just the opposite[20]. The bottom line is that team size should be matched to the goals of the team.

.

How Diverse Should My Team Be?

Team composition and team diversity often go hand in hand. Teams whose members have complementary skills are often more successful because members can see each other’s blind spots. One team member’s strengths can compensate for another’s weaknesses[21]. For example, consider the challenge that companies face when trying to forecast future sales of a given product. Workers who are educated as forecasters have the analytic skills needed for forecasting, but these workers often lack critical information about customers. Salespeople, in contrast, regularly communicate with customers, which means they’re in the know about upcoming customer decisions. But salespeople often lack the analytic skills, discipline, or desire to enter this knowledge into spreadsheets and software that will help a company forecast future sales. Putting forecasters and salespeople together on a team tasked with determining the most accurate product forecast each quarter makes the best use of each member’s skills and expertise.

Diversity in team composition can help teams come up with more creative and effective solutions. Research shows that teams that believe in the value of diversity performed better than teams that do not[22]. The more diverse a team is in terms of expertise, gender, age, and background, the more ability the group has to avoid the problems of groupthink[23]. For example, different educational levels for team members were related to more creativity in R&D teams and faster time to market for new products[24]. Members will be more inclined to make different kinds of mistakes, which means that they’ll be able to catch and correct those mistakes.

.

Team Roles

An inherent part of the team development process is assigning and maintaining team roles. A role is a set of expected behaviors that people are expected to perform because they hold specific formal or informal positions in a team and organization. Within a role there is

- Role identity: the certain actions and attitudes that are consistent with a particular role.

- Role perception: our own view of how we ourselves are supposed to act in a given situation. We engage in certain types of performance based on how we feel we’re supposed to act.

- Role expectations: how others believe one should act in a given situation

- Role conflict: conflict arises when the duties of one role conflict with the duties of another role.

Experts have attempted to categorize the team roles that have been proposed over the years. Here are some of the most common:

| Role | Description |

|---|---|

| Organizer | A team member who acts to structure what the team is doing. An Organizer also keeps track of accomplishments and how the team is progressing relative to goals and timelines. |

| Doer | A team member who willingly takes on work and gets things done. A Doer can be counted on to complete work, meet deadlines, and take on tasks to ensure the team’s success. This person should focus on goal accomplishment. |

| Challenger | A team member who will push the team to explore all aspects of a situation and to consider alternative assumptions, explanations, and solutions. A Challenger often asks “why” and is comfortable debating and critiquing. Think of this role as the team’s devil’s advocate. |

| Innovator | A team member who regularly generates new and creative ideas, strategies, and approaches for how the team can handle various situations and challenges. An Innovator often offers original and innovative suggestions. |

| Team builder | A team member who helps establish norms, supports decisions, and maintains a positive work atmosphere within the team. A Team Builder calms members when they are stressed, and motivates them when they are down. |

| Connector | A team member who helps bridge and connect the team with people, groups, or other stakeholders outside the team. Think of Connectors as “boundary spanners,” who ensure good working relationships between teams and “outsiders.” |

.

Team Norms

Norms are shared expectations about how things operate within a group or team. Just as new employees learn to understand and share the assumptions, norms, and values that are part of an organization’s culture, they also must learn the norms of their immediate team. This understanding helps teams be more cohesive and perform better. Norms are a powerful way of ensuring coordination within a team. For example, is it acceptable to be late for meetings? How prepared are you supposed to be at the meetings? Is it acceptable to criticize someone else’s work? These norms are shaped early during the life of a team and affect whether the team is productive, cohesive, and successful.

Square Wheels Exercise and Group Discussion

Sometimes it can be challenging to start a conversation around team ground rules and performance. The following exercise can be used to get individuals talking about what works and what doesn’t work in teams they’ve worked in and how your team can be designed most effectively.

What is happening in this picture represents how many organizations seem to operate. On a piece of paper have everyone in your team write on this form and identify as many of the key issues and opportunities for improvement as you can. Following this, have a conversation about what this illustration might mean for your own team.

.

Team Cohesion

Cohesiveness is the degree to which team members enjoy collaborating with the other members of the team and are motivated to stay in the team.

Cohesiveness is related to a team’s productivity. In fact, the higher the cohesiveness, the more there’s a chance of low productivity, if norms are not established well. If the team established solid, productive performance norms and their cohesiveness is high, then their productivity will ultimately be high. If the team did not establish those performance norms and their cohesiveness is high, then their productivity is doomed to be low. Think about a group of high school friends getting together after school to work on a project. If they have a good set of rules and tasks divided amongst them, they’ll get the project done and enjoy the work. And, without those norms, they will end up eating Hot Pockets and playing video games until it’s time to go home for dinner.

There are ways to increase cohesiveness within a team. A team leader can:

- shrink the size of the team to encourage its members to get to know each other and can interact with each other.

- increase the time the team spends together, and even increase the status of the team by making it seem difficult to gain entry to it.

- help the team come to an agreement around its goals.

- reward the entire team when those goals are achieved, rather than the individuals who made the biggest contributions to it.

- stimulate competition with other teams.

- isolate the team physically.

All of these actions can build the all-important cohesiveness that impacts productivity.

.

Group Think

It is also important to note that teams can also have their disadvantages. Consider the team groupthink. Groupthink is a group decision-making phenomenon that prevents a group from making good decisions. Groupthink occurs when the group is so enamored with the idea of agreement that the desire for consensus overrides and stifles the proposal and evaluation of realistic alternatives.

NASA’s Challenger

Perhaps the most famous and most studied example of Groupthink occurred when NASA launched the space shuttle Challenger in January of 1986. NASA had already canceled the launch due to weather once, and they were insistent that it goes off without a hitch on its newly rescheduled date of January 28, 1986. The makers of a fuel system O-ring, Thiokol, warned NASA that, based on cold weather predicted, that part might fail and yield disastrous consequences.

NASA’s internal processes and applied pressure kept those people from speaking up, and in an isolated meeting of Thiokol group members, they weighed the possibilities. The company might not be allowed to work with NASA again if they made too much noise. The part might not fail. And so, they agreed to not make any noise and to support NASA’s decision to launch. That morning, the Challenger exploded killing all seven crew members.

This tragedy and the mistakes made by NASA and Thiokol may be an example consequence of Groupthink. High-stakes decision-making with a group of people can create a clear group identity. In this case, it was the internal pressure of members feeling protective of a positive group image that led to Groupthink with disastrous consequences.

To avoid Groupthink, managers can take the following steps to help their employers. Managers can:

- monitor the group size.

- play an impartial role.

- encourage a group member to challenge the opposite view of the group’s decision.

- discuss the negative consequences of the decision before talking about the positive aspects.

A manager’s role can help when a group is working on something that has a high level of risk for the organization. A subcategory of Groupthink is Groupshift. Groupshift is a phenomenon in which a group of people influences one another about the perception of risk. Group members tend to exaggerate their initial positions when presenting their ideas to the rest of the group. Sometimes, the group jumps in and pushes that decision to a conservative shift, but more often, the group tends to move toward the riskier option.

Why does this happen? It’s been argued that, as group members become more familiar with each other, they become more bold and daring. Another theory states that we admire individuals who aren’t afraid of risk, and those individuals who present risky alternatives are often admired by other members. Regardless, managers do well to remember that groups often shift toward riskier tendencies and can do their best to mitigate those results.

.

Team Contracts

Scientific research, as well as experience working with thousands of teams, show that teams that are able to articulate and agree on established ground rules, goals, and roles and develop a team contract around these standards are better equipped to face challenges that may arise within the team[25]. Having a team contract does not necessarily mean that the team will be successful, but it can serve as a road map when the team veers off course. The following questions can help to create a meaningful team contract: