Let’s Define Power in the Workplace

Let’s Define Power

Numerous definitions of power abound in the literature on organizations. One of the earliest was suggested by Max Weber, the noted German sociologist, who defined power as “the probability that one actor within a social relationship will be in a position to carry out his own will despite resistance.”[1] Similarly, Emerson wrote, “The power of actor A over actor B is the amount of resistance on the part of B which can be potentially overcome by A.”[2] Following these and other definitions, we will define power for our purposes as an interpersonal relationship in which one individual (or group) has the ability to cause another individual (or group) to take an action that would not be taken otherwise.

In other words, power involves one person changing the behavior of another. It is important to note that in most organizational situations, we are talking about implied force to comply, not necessarily actual force. That is, person A has power over person B if person B believes that person A can, in fact, force person B to comply.

Power, Authority, and Leadership

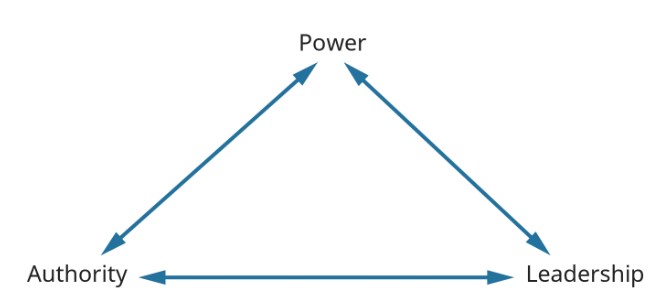

Clearly, the concept of power is closely related to the concepts of authority and leadership (see Figure 7.1). In fact, power has been referred to by some as “informal authority,” whereas authority has been called “legitimate power.” However, these three concepts are not the same, and important differences among the three should be noted[3].

.

As stated previously, power represents the capacity of one person or group to secure compliance from another person or group. Nothing is said here about the right to secure compliance—only the ability. In contrast, authority represents the right to seek compliance by others; the exercise of authority is backed by legitimacy. If a manager instructs a secretary to type certain letters, they presumably have the authority to make such a request. However, if the same manager asked the secretary to run personal errands, this would be outside the bounds of the legitimate exercise of authority. Although the secretary may still act on this request, the secretary’s compliance would be based on power or influence considerations, not authority.

Hence, the exercise of authority is based on group acceptance of someone’s right to exercise legitimate control. As Grimes notes, “What legitimates authority is the promotion or pursuit of collective goals that are associated with group consensus. The polar opposite, power, is the pursuit of individual or particularistic goals associated with group compliance.”[4]

Finally, leadership is the ability of one individual to elicit responses from another person that go beyond required or mechanical compliance. It is this voluntary aspect of leadership that sets it apart from power and authority. Hence, we often differentiate between headship and leadership. A department head may have the right to require certain actions, whereas a leader has the ability to inspire certain actions. Although both functions may be served by the same individual, such is clearly not always the case.