Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the main features and prevalence of obsessive-compulsive disorder, body dysmorphic disorder, and hoarding disorder

- Understand some of the factors in the development of obsessive-compulsive disorder

Obsessive-compulsive and related disorders are a group of overlapping disorders that generally involve intrusive, unpleasant thoughts and repetitive behaviours. Many of us experience unwanted thoughts from time to time (e.g., craving double cheeseburgers when dieting), and many of us engage in repetitive behaviours on occasion (e.g., pacing when nervous). However, obsessive-compulsive and related disorders elevate the unwanted thoughts and repetitive behaviours to a status so intense that these cognitions and activities disrupt daily life. Included in this category are obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), body dysmorphic disorder, and hoarding disorder.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

People with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) experience thoughts and urges that are intrusive and unwanted (obsessions) and/or the need to engage in repetitive behaviours or mental acts (compulsions). A person with this disorder might, for example, spend hours each day washing his hands or constantly checking and rechecking to make sure that a stove, faucet, or light has been turned off.

Obsessions are more than just unwanted thoughts that seem to randomly jump into our head from time to time, such as recalling an insensitive remark a coworker made recently, and they are more significant than day-to-day worries we might have, such as justifiable concerns about being laid off from a job. Rather, obsessions are characterized as persistent, unintentional, and unwanted thoughts and urges that are highly intrusive, unpleasant, and distressing (APA, 2013). Common obsessions include concerns about germs and contamination, doubts (“Did I turn the water off?”), order and symmetry (“I need all the spoons in the tray to be arranged a certain way”), and urges that are aggressive or lustful. Usually, the person knows that such thoughts and urges are irrational and thus tries to suppress or ignore them, but has an extremely difficult time doing so. These obsessive symptoms sometimes overlap, such that someone might have both contamination and aggressive obsessions (Abramowitz & Siqueland, 2013).

Compulsions are repetitive and ritualistic acts that are typically carried out primarily as a means to minimize the distress that obsessions trigger or to reduce the likelihood of a feared event (APA, 2013). Compulsions often include such behaviours as repeated and extensive hand washing, cleaning, checking (e.g., that a door is locked), and ordering (e.g., lining up all the pencils in a particular way), and they also include such mental acts as counting, praying, or reciting something to oneself (Figure 15.11). Compulsions characteristic of OCD are not performed out of pleasure, nor are they connected in a realistic way to the source of the distress or feared event. Approximately 2% of the Canadian population will experience OCD in their lifetime (Langlois et al., 2011) and, if left untreated, OCD tends to be a chronic condition creating lifelong interpersonal and psychological problems (Norberg, Calamari, Cohen, & Riemann, 2008).

Body Dysmorphic Disorder

An individual with body dysmorphic disorder is preoccupied with a perceived flaw in physical appearance that is either nonexistent or barely noticeable to other people (APA, 2013). These perceived physical defects cause people to think they are unattractive, ugly, hideous, or deformed. These preoccupations can focus on any bodily area, but they typically involve the skin, face, or hair. The preoccupation with imagined physical flaws drives the person to engage in repetitive and ritualistic behavioural and mental acts, such as constantly looking in the mirror, trying to hide the offending body part, comparisons with others, and, in some extreme cases, cosmetic surgery (Phillips, 2005). An estimated 2.4% of the adults in Canada and the United States meet the criteria for body dysmorphic disorder, with slightly higher rates in women than in men (APA, 2013).

Hoarding Disorder

Although hoarding was traditionally considered to be a symptom of OCD, considerable evidence suggests that hoarding represents an entirely different disorder (Mataix-Cols et al., 2010). People with hoarding disorder cannot bear to part with personal possessions, regardless of how valueless or useless these possessions are. As a result, these individuals accumulate excessive amounts of usually worthless items that clutter their living areas (Figure 15.12). Often, the quantity of cluttered items is so excessive that the person is unable to use his kitchen, or sleep in his bed. People who suffer from this disorder have great difficulty parting with items because they believe the items might be of some later use, or because they form a sentimental attachment to the items (APA, 2013). Importantly, a diagnosis of hoarding disorder is made only if the hoarding is not caused by another medical condition and if the hoarding is not a symptom of another disorder (e.g., schizophrenia) (APA, 2013).

Causes of OCD

The results of family and twin studies suggest that OCD has a moderate genetic component. The disorder is five times more frequent in the first-degree relatives of people with OCD than in people without the disorder (Nestadt et al., 2000). Additionally, the concordance rate of OCD among identical twins is around 57%; however, the concordance rate for fraternal twins is 22% (Bolton, Rijsdijk, O’Connor, Perrin, & Eley, 2007). Studies have implicated about two dozen potential genes that may be involved in OCD; these genes regulate the function of three neurotransmitters: serotonin, dopamine, and glutamate (Pauls, 2010). Many of these studies included small sample sizes and have yet to be replicated. Thus, additional research needs to be done in this area.

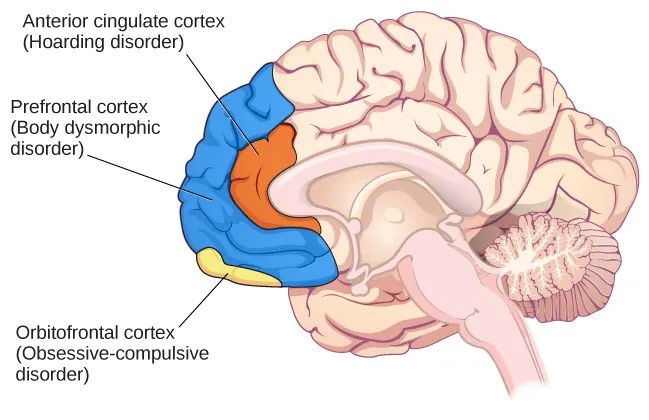

A brain region that is believed to play a critical role in OCD is the orbitofrontal cortex (Kopell & Greenberg, 2008), an area of the frontal lobe involved in learning and decision-making (Rushworth, Noonan, Boorman, Walton, & Behrens, 2011) (Figure 15.13). In people with OCD, the orbitofrontal cortex becomes especially hyperactive when they are provoked with tasks in which, for example, they are asked to look at a photo of a toilet or of pictures hanging crookedly on a wall (Simon, Kaufmann, Müsch, Kischkel, & Kathmann, 2010). The orbitofrontal cortex is part of a series of brain regions that, collectively, is called the OCD circuit; this circuit consists of several interconnected regions that influence the perceived emotional value of stimuli and the selection of both behavioural and cognitive responses (Graybiel & Rauch, 2000). As with the orbitofrontal cortex, other regions of the OCD circuit show heightened activity during symptom provocation (Rotge et al., 2008), which suggests that abnormalities in these regions may produce the symptoms of OCD (Saxena, Bota, & Brody, 2001). Consistent with this explanation, people with OCD show a substantially higher degree of connectivity of the orbitofrontal cortex and other regions of the OCD circuit than do those without OCD (Beucke et al., 2013).

The findings discussed above were based on imaging studies, and they highlight the potential importance of brain dysfunction in OCD. However, one important limitation of these findings is the inability to explain differences in obsessions and compulsions. Another limitation is that the correlational relationship between neurological abnormalities and OCD symptoms cannot imply causation (Abramowitz & Siqueland, 2013).

CONNECT THE CONCEPTS: Conditioning and OCD

The symptoms of OCD have been theorized to be learned responses, acquired and sustained as the result of a combination of two forms of learning: classical conditioning and operant conditioning (Mowrer, 1960; Steinmetz, Tracy, & Green, 2001). Specifically, the acquisition of OCD may occur first as the result of classical conditioning, whereby a neutral stimulus becomes associated with an unconditioned stimulus that provokes anxiety or distress. When an individual has acquired this association, subsequent encounters with the neutral stimulus trigger anxiety, including obsessive thoughts; the anxiety and obsessive thoughts (which are now a conditioned response) may persist until she identifies some strategy to relieve it. Relief may take the form of a ritualistic behaviour or mental activity that, when enacted repeatedly, reduces the anxiety. Such efforts to relieve anxiety constitute an example of negative reinforcement (a form of operant conditioning). Recall from the chapter on learning that negative reinforcement involves the strengthening of behaviour through its ability to remove something unpleasant or aversive. Hence, compulsive acts observed in OCD may be sustained because they are negatively reinforcing, in the sense that they reduce anxiety triggered by a conditioned stimulus.

Suppose an individual with OCD experiences obsessive thoughts about germs, contamination, and disease whenever she encounters a doorknob. What might have constituted a viable unconditioned stimulus? Also, what would constitute the conditioned stimulus, unconditioned response, and conditioned response? What kinds of compulsive behaviours might we expect, and how do they reinforce themselves? What is decreased? Additionally, and from the standpoint of learning theory, how might the symptoms of OCD be treated successfully?

a group of overlapping disorders that generally involve intrusive, unpleasant thoughts and repetitive behaviours

characterized as persistent, unintentional, and unwanted thoughts and urges that are highly intrusive, unpleasant, and distressing

repetitive and ritualistic acts that are typically carried out primarily as a means to minimize the distress that obsessions trigger or to reduce the likelihood of a feared event