Humanistic Approaches

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Discuss the contributions of Abraham Maslow and Carl Rogers to personality development

As the “third force” in psychology, humanism is touted as a reaction both to the pessimistic determinism of psychoanalysis, with its emphasis on psychological disturbance, and to the behaviourists’ view of humans passively reacting to the environment, which has been criticized as making people out to be personality-less robots. It does not suggest that psychoanalytic, behaviourist, and other points of view are incorrect but argues that these perspectives do not recognize the depth and meaning of human experience, and fail to recognize the innate capacity for self-directed change and transforming personal experiences. This perspective focuses on how healthy people develop.

Abraham Maslow

One pioneering humanist, Abraham Maslow, studied people who he considered to be healthy, creative, and productive, including Albert Einstein, Eleanor Roosevelt, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, and others. Maslow (1950, 1970) found that such people share similar characteristics, such as being open, creative, loving, spontaneous, compassionate, concerned for others, and accepting of themselves.

When you study motivation, you will learn about one of the best-known humanistic theories, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory, in which Maslow proposes that human beings have certain needs in common and that these needs must be met in a certain order. The highest need is the need for self-actualization, which is the achievement of our fullest potential. Maslow differentiated between needs that motivate us to fulfill something that is missing and needs that inspire us to grow. He believed that many emotional and behavioural concerns arise as a result of failing to meet these hierarchical needs.

Carl Rogers

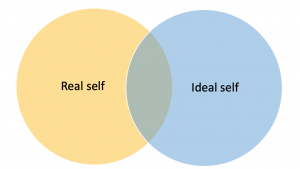

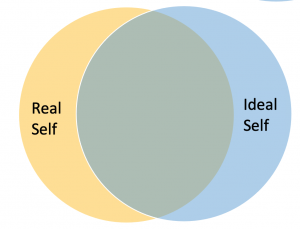

Another humanistic theorist was Carl Rogers (Figure 8.12). One of Rogers’s main ideas about personality regards self-concept, our thoughts and feelings about ourselves. How would you respond to the question, “Who am I?” Your answer can show how you see yourself. If your response is primarily positive, then you tend to feel good about who you are, and you see the world as a safe and positive place. If your response is mainly negative, then you may feel unhappy with who you are. Rogers further divided the self into two categories: the ideal self and the real self (Figure 8.13). The ideal self is the person that you would like to be; the real self is the person you actually are. Rogers focused on the idea that we need to achieve consistency between these two selves. We experience congruence when our thoughts about our real self and ideal self are very similar—in other words, when our self-concept is accurate. High congruence leads to a greater sense of self-worth and a healthy, productive life. Parents can help their children achieve this by giving them unconditional positive regard, or unconditional love. According to Rogers (1980), “As persons are accepted and prized, they tend to develop a more caring attitude towards themselves” (p. 116). Conversely, when there is a great discrepancy between our ideal and actual selves, we experience a state Rogers called incongruence, which can lead to maladjustment. Both Rogers’s and Maslow’s theories focus on individual choices and do not believe that biology is deterministic.

|

|

Figure 8.13 Rogers’ theory of the self.

is the person that you would like to be

the person you actually are