The Role of Supply, Demand, and Competition

Under a mixed economy, such as in Canada, businesses decide which goods to produce or services to offer and how they are priced. Because there are many businesses making goods or providing services, customers can choose from a wide array of products. The competition for sales among businesses is a vital part of our economic system. Economists have identified four types of competition—perfect competition, monopolistic competition, oligopoly, and monopoly.

Perfect Competition

Perfect competition exists when there are many consumers buying a standardized product from numerous small businesses. Because no seller is big enough or influential enough to affect the price, sellers and buyers accept the going price. For example, when a commercial fisher brings his fish to the local market, he has little control over the price he gets and must accept the going market price.

The Basics of Supply and Demand

To appreciate how perfect competition works, we need to understand how buyers and sellers interact in a market to set prices. In a market characterized by perfect competition, price is determined through the mechanisms of supply and demand. Prices are influenced both by the supply of products from sellers and by the demand for products by buyers.

To illustrate this concept, let’s create a supply and demand schedule for one particular good sold at one point in time. Then we’ll define demand and create a demand curve and define supply and create a supply curve. Finally, we’ll see how supply and demand interact to create an equilibrium price—the price at which buyers are willing to purchase the amount that sellers are willing to sell.

Demand and the Demand Curve

Demand is the quantity of a product that buyers are willing to purchase at various prices. The quantity of a product that people are willing to buy depends on its price. You’re typically willing to buy less of a product when prices rise and more of a product when prices fall. Generally speaking, we find products more attractive at lower prices, and we buy more at lower prices because our income goes further.

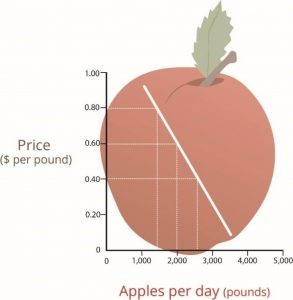

Figure 1.5: The Demand Curve

Using this logic, we can construct a demand curve that shows the quantity of a product that will be demanded at different prices. Let’s assume that the diagram “The Demand Curve” represents the daily price and quantity of apples sold by farmers at a local market. Note that as the price of apples goes down, buyers’ demand goes up. Thus, if a pound of apples sells for $0.80, buyers will be willing to purchase only fifteen hundred pounds per day. But if apples cost only $0.60 a pound, buyers will be willing to purchase two thousand pounds. At $0.40 a pound, buyers will be willing to purchase twenty-five hundred pounds.

Supply and the Supply Curve

Supply is the quantity of a product that sellers are willing to sell at various prices. The quantity of a product that a business is willing to sell depends on its price. Businesses are more willing to sell a product when the price rises and less willing to sell it when prices fall. Again, this fact makes sense: businesses are set up to make profits, and there are larger profits to be made when prices are high.

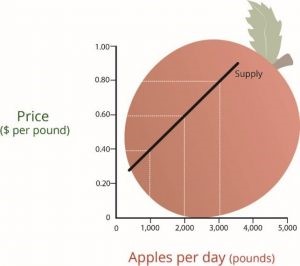

Figure 1.6: The Supply Curve

Now we can construct a supply curve that shows the number of apples that farmers would be willing to sell at different prices, regardless of demand. As you can see in “The Supply Curve”, the supply curve goes opposite from the demand curve: as prices rise, the quantity of apples that farmers are willing to sell also increases. The supply curve shows that farmers are willing to sell only a thousand pounds of apples when the price is $0.40 a pound, two thousand pounds when the price is $0.60, and three thousand pounds when the price is $0.80.

Equilibrium Price

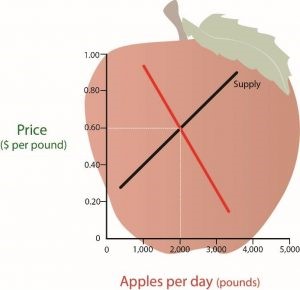

We can now see how the market mechanism works under perfect competition. We do this by plotting both the supply curve and the demand curve on one graph, as we’ve done in the figure below, “The Equilibrium Price”. The point at which the two curves intersect is the equilibrium price.

Figure 1.7: The Equilibrium Price

You can see in “The Equilibrium Price” that the supply and demand curves intersect at the price of $0.60 and quantity of two thousand pounds. Thus, $0.60 is the equilibrium price: at this price, the quantity of apples demanded by buyers equals the number of apples that farmers are willing to supply. If a single farmer tries to charge more than $0.60 for a pound of apples, he won’t sell very many because other suppliers are making them available for less. As a result, his profits will go down. If, on the other hand, a farmer tries to charge less than the equilibrium price of $0.60 a pound, he will sell more apples but his profit per pound will be less than at the equilibrium price. With profit being the motive, there is no incentive to drop the price.

What have you learned in this discussion? Without outside influences, markets in an environment of perfect competition will arrive at an equilibrium point at which both buyers and sellers are satisfied. But you must be aware that this is a very simplistic example. Things are much more complex in the real world. For one thing, markets rarely operate without outside influences. Sometimes, sellers supply more of a product than buyers are willing to purchase; in that case, there’s a surplus. Sometimes, they don’t produce enough of a product to satisfy demand; then we have a shortage.

Circumstances also have a habit of changing. What would happen, for example, if incomes rose and buyers were willing to pay more for apples? The demand curve would change, resulting in an increase in equilibrium price. This outcome makes intuitive sense: as demand increases, prices will go up. What would happen if apple crops were larger than expected because of favorable weather conditions? Farmers might be willing to sell apples at lower prices rather than letting part of the crop spoil. If so, the supply curve would shift, resulting in another change in equilibrium price: the increase in supply would bring down prices.

What is Supply and Demand? [1]

Monopolistic Competition, Oligopoly, and Monopoly

As mentioned previously, economists have identified four types of competition—perfect competition, monopolistic competition, oligopoly, and monopoly. Perfect competition was discussed in the last section; we’ll cover the remaining three types of competition here.

Characteristic |

Perfect Competition |

Monopolistic Competition |

Oligopoly |

Monopoly |

| Number of firms | Very many | Many | A few | One |

| Type of product | Homogeneous | Differentiated | Homogeneous or Differentiated | Homogeneous |

| Barriers to entry or exit from industry | No substantial barriers | Minor barriers | Considerable barriers | Extremely high barriers |

| Examples | Agriculture | Retail trade | Banking | Public utilities |

Monopolistic Competition

In monopolistic competition, we still have many sellers (as we had under perfect competition). Now, however, they don’t sell identical products. Instead, they sell differentiated products—products that differ somewhat or are perceived to differ, even though they serve a similar purpose. Products can be differentiated in a number of ways, including quality, style, convenience, location, and brand name. Some people prefer Coke over Pepsi, even though the two products are quite similar. But what if there was a substantial price difference between the two? In that case, buyers could be persuaded to switch from one to the other. Thus, if Coke has a big promotional sale at a supermarket chain, some Pepsi drinkers might switch (at least temporarily).

How is product differentiation accomplished? Sometimes, it’s simply geographical; you probably buy gasoline at the station closest to your home regardless of the brand. At other times, perceived differences between products are promoted by advertising designed to convince consumers that one product is different from another—and better than it. Regardless of customer loyalty to a product, however, if its price goes too high, the seller will lose business to a competitor. Under monopolistic competition, therefore, companies have only limited control over price.

Oligopoly

Oligopoly means few sellers. In an oligopolistic market, each seller supplies a large portion of all the products sold in the marketplace. In addition, because the cost of starting a business in an oligopolistic industry is usually high, the number of firms entering it is low. Companies in oligopolistic industries include such large-scale enterprises as automobile companies and airlines. As large firms supply a sizable portion of a market, these companies have some control over the prices they charge. But there’s a catch: because products are fairly similar when one company lowers prices, others are often forced to follow suit to remain competitive. You see this practice all the time in the airline industry: When American Airlines announces a fare decrease, Continental, United Airlines, and others do likewise. When one automaker offers a special deal, its competitors usually come up with similar promotions.

Monopoly

In terms of the number of sellers and degree of competition, a monopoly lies at the opposite end of the spectrum from perfect competition. In perfect competition, there are many small companies, none of which can control prices; they simply accept the market price determined by supply and demand. In a monopoly, however, there’s only one seller in the market. The market could be a geographical area, such as a city or a regional area, and doesn’t necessarily have to be an entire country.

There are few monopolies in Canada because the government limits them. Most fall into one of two categories: natural and legal. Natural monopolies include public utilities, such as electricity and gas suppliers. Such enterprises require huge investments, and it would be inefficient to duplicate the products that they provide. They inhibit competition, but they’re legal because they’re important to society. In exchange for the right to conduct business without competition, they’re regulated. For instance, they can’t charge whatever prices they want, but they must adhere to government-controlled prices. As a rule, they’re required to serve all customers, even if doing so isn’t cost-efficient.

A legal monopoly arises when a company receives a patent giving it exclusive use of an invented product or process. Patents are issued for a limited time, generally twenty years. During this period, other companies can’t use the invented product or process without permission from the patent holder. Patents allow companies a certain period to recover the heavy costs of researching and developing products and technologies. A classic example of a company that enjoyed a patent-based legal monopoly is Polaroid, which for years held exclusive ownership of instant-film technology. Polaroid priced the product high enough to recoup, over time, the high cost of bringing it to market. Without competition, in other words, it enjoyed a monopolistic position in regard to pricing.

Are monopolies good, bad, or both?

Check out this video to further explore market structures: Monopolies and Anti-Competitive Markets

- IMF.(2017, December 7). What is supply and demand? [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2Wp-diDRVKI ↵

Exists when there are many consumers buying a standardized product from numerous small businesses. Because no seller is big enough or influential enough to affect the price, sellers and buyers accept the going price.

The quantity of a product that buyers are willing to purchase at various prices.

The quantity of a product that sellers are willing to sell at various prices.

The price at which the quantity of a good or service demanded by consumers equals the quantity supplied by producers. At this price, there is no surplus of goods or shortage, meaning the market is in balance. Sellers are selling all the goods they have produced, and buyers are getting all the goods they want to purchase.

Many businesses who sell differentiated products - products that differ somewhat or are perceived to differ, even though they serve a similar product.

A fewer number of sellers, each selling supplying a large portion of the products sold in the marketplace. Due to the cost of entrance, the number of firms entering the market is low.

There is only one seller in the market. Monopolies in Canada are limited by the government and fall into one of two categories: natural and legal.