The Time Value of Money

Do you sometimes wonder where your money goes? Do you worry about how you’ll pay off your student loans? Would you like to buy a new car or even a home someday and you’re not sure where you’ll get the money? If these questions seem familiar to you, you could benefit from help in managing your personal finances, which this chapter will seek to provide.

.

Let’s say that you’re twenty-eight and single. You have a good education and a good job—you’re pulling down $60K working with a local accounting firm. You have $6,000 in a retirement savings account, and you carry three credit cards. You plan to buy a condo in two or three years, and you want to take your dream trip to the world’s hottest surfing spots within five years. Your only big worry is the fact that you’re $70,000 in debt, due to student loans, your car loan, and credit card debt. Even though you’ve been gainfully employed for a total of six years now, you haven’t been able to make a dent in that $70,000. You can afford the necessities of life and then some, but you’ve occasionally wondered if you’re ever going to have enough income to put something toward that debt. [1]

Let’s say that you’re twenty-eight and single. You have a good education and a good job—you’re pulling down $60K working with a local accounting firm. You have $6,000 in a retirement savings account, and you carry three credit cards. You plan to buy a condo in two or three years, and you want to take your dream trip to the world’s hottest surfing spots within five years. Your only big worry is the fact that you’re $70,000 in debt, due to student loans, your car loan, and credit card debt. Even though you’ve been gainfully employed for a total of six years now, you haven’t been able to make a dent in that $70,000. You can afford the necessities of life and then some, but you’ve occasionally wondered if you’re ever going to have enough income to put something toward that debt. [1]

You’re not alone! The average student in Canada will graduate in 2018 having accumulated over $27,000 in student debt. However, this is not the only financial problem in Canada. Canadian household debt has reached a record high of over $2.08 trillion as of September 2017, that is $1.68 of debt for every $1 of income.

Personal financial literacy is more important than ever in Canada. As a country, we need to improve our financial literacy. The Bank for International Settlements, an “international watchdog” regarding the country’s economic risk, has warned that Canada’s banking system is at risk due to the rising collective household debt level.

Time Is Money

The fact that you have to choose a career at an early stage in your financial life cycle isn’t the only reason that you need to start early, on your financial planning. Let’s assume, for instance, that it’s your eighteenth birthday and that on this day you take possession of $10,000 that your grandparents put in trust for you. You could, of course, spend it; in particular, it would probably cover the cost of flight training for a private pilot’s license—something you’ve always wanted but were convinced that you couldn’t afford right away. Your grandfather, of course, suggests that you put it into some kind of savings account. This way, your $10,000 could take advantage of something called interest. Interest is the charge for the privilege of borrowing money, typically expressed as an annual percentage rate, or is the payment made to you from the investing institution on top of the principal amount you invested of $10,000. If you just wait until you finish college, he says, and if you can find a savings plan that pays 5 percent interest, you’ll have the $10,000 plus about another $2,000 for something else or to invest.

The total amount you’ll have— $12,000—piques your interest. If that $10,000 could turn itself into $12,000 after sitting around for four years, what would it be worth if you held on to it until you did retire—say, at age sixty-five? A quick trip to the Internet to find a compound-interest calculator informs you that, forty-seven years later, your $10,000 will have grown to $104,345 (assuming a 5 percent interest rate). That’s not enough to retire on, but it would be a good start. On the other hand, what if that four years in college had paid off the way you planned, so that once you get a good job you’re able to add, say, another $10,000 to your retirement savings account every year until age sixty-five? At that rate, you’ll have amassed a nice little nest egg of slightly more than $1.6 million.

Compound Interest

In your efforts to appreciate the potential of your $10,000 to multiply itself, you have acquainted yourself with two of the most important concepts in finance. As we’ve already indicated, one is the principle of compound interest, which refers to the effect of earning interest on your interest.

Let’s say, for example, that you take your grandfather’s advice and invest your $10,000 (your principal) in a savings account at an annual interest rate of 5 percent. Over the first year, your investment will earn $500 in interest and grow to $10,500. If you now reinvest the entire $10,500 at the same 5 percent annual rate, you’ll earn another $525 in interest, giving you a total investment at the end of year 2 of $11,025. And so forth. And that’s how you can end up with $81,496.67 at age sixty-five.

Prefer a video to help you decipher and understand compound interest? Watch Khan Academy’s seven-minute explanation: [2]

Time Value of Money

You’ve also encountered the principle of the time value of money—the principle whereby a dollar received in the present is worth more than a dollar received in the future. If there’s one thing that we’ve stressed throughout this chapter so far, it’s the fact that most people prefer to consume now rather than in the future. If you borrow money from me, it’s because you can’t otherwise buy something that you want at the present time. If I lend it to you, I must forego my opportunity to purchase something I want at the present time. I will do so only if I can get some compensation for making that sacrifice, and that’s why I’m going to charge you interest. And you’re going to pay the interest because you need the money to buy what you want to buy now. How much interest should we agree on? In theory, it could be just enough to cover the cost of my lost opportunity, but there are, of course, other factors. Inflation, which is the general increase in prices of goods and services and the corresponding decrease in the purchasing power of money, for example, will have eroded the value of my money by the time I get it back from you. In addition, while I would be taking no risk in loaning money to the Canadian government, I am taking a risk in lending it to you. Our agreed-on rate will reflect such factors. [3]

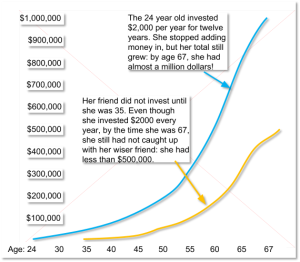

Finally, the time value of money principle also states that a dollar received today starts earning interest sooner than one received tomorrow. Let’s say, for example, that you receive $2,000 in cash gifts when you graduate from college. At age twenty-three, with your college degree in hand, you get a decent job and don’t have an immediate need for that $2,000. So you put it into an account that pays 10 percent compounded and you add another $2,000 ($167 per month) to your account every year for the next eleven years. [4] The blue line in the graph below shows how much your account will earn each year and how much money you’ll have at certain ages between twenty-four and sixty-seven.

Figure 9.1: The Power of Compound Interest

As you can see, you’d have nearly $52,000 at age thirty-six and a little more than $196,000 at age fifty; at age sixty-seven, you’d be just a bit short of $1 million. The yellow line in the graph shows what you’d have if you hadn’t started saving $2,000 a year until you were age thirty-six. As you can also see, you’d have a respectable sum at age sixty-seven—but less than half of what you would have accumulated by starting at age twenty-three. More importantly, even to accumulate that much, you’d have to add $2,000 per year for a total of thirty-two years, not just twelve.

Here’s another way of looking at the same principle. Suppose that you’re twenty years old, don’t have $2,000, and don’t want to attend college full-time. You are, however, a hard worker and a conscientious saver, and one of your financial goals is to accumulate a $1 million retirement nest egg. If you can put $33 a month into an account that pays 12 percent interest compounded, [5] you can have your $1 million by age sixty-seven. That is if you start at age twenty. As you can see from the figure below, if you wait until you’re twenty-one to start saving, you’ll need $37 a month. If you wait until you’re thirty, you’ll have to save $109 a month, and if you procrastinate until you’re forty, the ante goes up to $366 a month. [6] Unfortunately in today’s low interest rate environment, finding a 10 to 12% return is not likely. Nevertheless, these figures illustrate the significant benefit of saving early.

Have to Save a Million Dollars by Age 67

| If you make your first payment at: | You will have to save this amount each month: |

| 20 years old | $33 |

| 21 years old | $37 |

| 22 years old | $42 |

| 23 years old | $47 |

| 24 years old | $53 |

| 25 years old | $60 |

| 26 years old | $67 |

| 27 years old | $76 |

| 28 years old | $85 |

| 30 years old | $109 |

| 35 years old | $199 |

| 40 years old | $366 |

| 50 years old | $1,319 |

| 60 years old | $6,253 |

The reason should be fairly obvious: a dollar saved today not only starts earning interest sooner than one saved tomorrow (or ten years from now) but also can ultimately earn a lot more money in the long run. Starting early means in your twenties—early in stage 1 of your financial life cycle. As one well-known financial advisor puts it, “If you’re in your 20s and you haven’t yet learned how to delay gratification, your life is likely to be a constant financial struggle.” [7]

Opportunity Cost

Opportunity cost is an economic concept that refers to the potential benefit an individual, investor, or business misses out on when choosing one alternative over another. While it can be applied in many contexts, in personal finance, opportunity cost is used to weigh the potential benefits of different financial decisions.

.

For example, let’s say you have $1,000 that you can either use to go on a vacation or invest in a mutual fund. If you choose to go on vacation, the opportunity cost is the potential return you could have earned by investing the money. Conversely, if you invest the money, the opportunity cost is the enjoyment and relaxation you could have experienced from the vacation.

For example, let’s say you have $1,000 that you can either use to go on a vacation or invest in a mutual fund. If you choose to go on vacation, the opportunity cost is the potential return you could have earned by investing the money. Conversely, if you invest the money, the opportunity cost is the enjoyment and relaxation you could have experienced from the vacation.

Understanding opportunity costs helps individuals make informed decisions about their money. When making any financial decision, it’s essential to consider not just the potential returns of the chosen option, but also what you’re potentially giving up by not choosing the alternatives.

Ultimately, considering opportunity costs can help individuals better manage their money by highlighting the potential trade-offs of different financial decisions, and can lead to a more strategic and satisfying allocation of financial resources.

- USA Today (2005). “Financial Diet” Retrieved from: http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/money/perfi/basics/financial-diet-digest-2005.htm ↵

- Khan Academy. (2013, September, 28). Compound interest introduced | Interest and debt | Finance & Capital Markets | Khan Academy [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rm6UdfRs3gw ↵

- Gallager T. J., & and Andrews, J. D. Jr., (2003). Financial Management: Principles and Practice, 3rd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. p. 34, 196. ↵

- The 10% rate is not realistic in today’s economic market and is used for illustrative purposes only. ↵

- Again, this interest rate is unrealistic in today’s market and is used for illustrative purposes only. ↵

- Keown, A. J. (2007). Personal Finance: Turning Money into Wealth, 4th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. p. 23. ↵

- AllFinancialMatters (2006). “An Interview with Jonathan Clements – Part 2.” ↵

The principle whereby a dollar received in the present is worth more than a dollar received in the future.

An economic concept that refers to the potential benefit an individual, investor, or business misses out on when choosing one alternative over another.