16.2 Self-Concept and Dimensions of Self

Learning Objective

- Define and discuss self-concept.

Again we’ll return to the question “what are you doing?” as one way to approach self-concept. If we define ourselves through our actions, what might those actions be, and are we no longer ourselves when we no longer engage in those activities? Psychologist Steven Pinker defines the conscious present as about three seconds for most people. Everything else is past or future (Pinker, S., 2009). Who are you at this moment in time, and will the self you become an hour from now be different from the self that is reading this sentence right now?

Just as the communication process is dynamic, not static (i.e., always changing, not staying the same), you too are a dynamic system. Physiologically your body is in a constant state of change as you inhale and exhale air, digest food, and cleanse waste from each cell. Psychologically you are constantly in a state of change as well. Some aspects of your personality and character will be constant, while others will shift and adapt to your environment and context. That complex combination contributes to the self you call you. We may choose to define self as one’s own sense of individuality, personal characteristics, motivations, and actions (McLean, S., 2005), but any definition we create will fail to capture who you are, and who you will become.

Self-Concept

Our self-concept is “what we perceive ourselves to be,” (McLean, S., 2005) and involves aspects of image and esteem. How we see ourselves and how we feel about ourselves influences how we communicate with others. What you are thinking now and how you communicate impacts and influences how others treat you. Charles Cooley calls this concept the looking-glass self. We look at how others treat us, what they say and how they say it, for clues about how they view us to gain insight into our own identity. Leon Festinger added that we engage in social comparisons, evaluating ourselves in relation to our peers of similar status, similar characteristics, or similar qualities (Festinger, L., 1954).

The ability to think about how, what, and when we think, and why, is critical to intrapersonal communication. Animals may use language and tools, but can they reflect on their own thinking? Self-reflection is a trait that allows us to adapt and change to our context or environment, to accept or reject messages, to examine our concept of ourselves and choose to improve.

Internal monologue refers to the self-talk of intrapersonal communication. It can be a running monologue that is rational and reasonable, or disorganized and illogical. It can interfere with listening to others, impede your ability to focus, and become a barrier to effective communication. Alfred Korzybski suggested that the first step in becoming conscious of how we think and communicate with ourselves was to achieve an inner quietness, in effect “turning off” our internal monologue (Korzybski, A., 1933). Learning to be quiet inside can be a challenge. We can choose to listen to others when they communicate through the written or spoken word while refraining from preparing our responses before they finish their turn is essential. We can take mental note of when we jump to conclusions from only partially attending to the speaker or writer’s message. We can choose to listen to others instead of ourselves.

One principle of communication is that interaction is always dynamic and changing. That interaction can be internal, as in intrapersonal communication, but can also be external. We may communicate with one other person and engage in interpersonal communication. If we engage two or more individuals (up to eight normally), group communication is the result. More than eight normally results in subdivisions within the group and a reversion to smaller groups of three to four members (McLean, S., 2005) due to the ever-increasing complexity of the communication process. With each new person comes a multiplier effect on the number of possible interactions, and for many that means the need to establish limits.

Dimensions of Self

Who are you? You are more than your actions, and more than your communication, and the result may be greater than the sum of the parts, but how do you know yourself? In the first of the Note 16.1 “Introductory Exercises” for this chapter, you were asked to define yourself in five words or less. Was it a challenge? Can five words capture the essence of what you consider yourself to be? Was your twenty to fifty description easier? Or was it equally challenging? Did your description focus on your characteristics, beliefs, actions, or other factors associated with you? If you compared your results with classmates or coworkers, what did you observe? For many, these exercises can prove challenging as we try to reconcile the self-concept we perceive with what we desire others to perceive about us, as we try to see ourselves through our interactions with others, and as we come to terms with the idea that we may not be aware or know everything there is to know about ourselves.

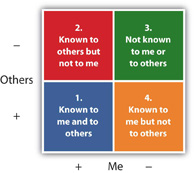

Joseph Luft and Harry Ingram, gave considerable thought and attention to these dimensions of self, which are represented in Figure 16.1 “Luft and Ingram’s Dimensions of Self”. In the first quadrant of the figure, information is known to you and others, such as your height or weight. The second quadrant represents things others observe about us that we are unaware of, like how many times we say “umm” in the space of five minutes. The third quadrant involves information that you know, but do not reveal to others. It may involve actively hiding or withholding information, or may involve social tact, such as thanking your Aunt Martha for the large purple hat she’s given you that you know you will never wear. Finally, the fourth quadrant involves information that is unknown to you and your conversational partners. For example, a childhood experience that has been long forgotten or repressed may still motivate you. As another example, how will you handle an emergency after you’ve received first aid training? No one knows because it has not happened.

These dimensions of self serve to remind us that we are not fixed—that freedom to change combined with the ability to reflect, anticipate, plan, and predict allows us to improve, learn, and adapt to our surroundings. By recognizing that we are not fixed in our concept of “self,” we come to terms with the responsibility and freedom inherent in our potential humanity.

In the context of business communication, the self plays a central role. How do you describe yourself? Do your career path, job responsibilities, goals, and aspirations align with what you recognize to be your talents? How you represent “self,” through your résumé, in your writing, in your articulation and presentation—these all play an important role as you negotiate the relationships and climate present in any organization.

Key Takeaway

Self-concept involves multiple dimensions and is expressed in internal monologue and social comparisons.

Exercises

- Examine your academic or professional résumé—or, if you don’t have one, create one now. According to the dimensions of self described in this section, which dimensions contribute to your résumé? Discuss your results with your classmates.

- How would you describe yourself in terms of the dimensions of self as shown in Figure 16.1 “Luft and Ingram’s Dimensions of Self”? Discuss your thoughts with a classmate.

- Can you think of a job or career that would be a good way for you to express yourself? Are you pursuing that job or career? Why or why not? Discuss your answer with a classmate.

References

Cooley, C. (1922). Human nature and the social order (Rev. ed.). New York, NY: Scribners.

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relationships, 7, 117–140.

Korzybski, A. (1933). Science and sanity. Lancaster, PA: International Non-Aristotelian Library Publish Co.

Luft, J. (1970). Group processes: An introduction to group dynamics (2nd ed.). Palo Alto, CA: National Press Group.

Luft, J., & Ingham, H. (1955). The Johari Window: A graphic model for interpersonal relations. Los Angeles: University of California Western Training Lab.

McLean, S. (2005). The basics of interpersonal communication. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Pinker, S. (2009). The stuff of thought: Language as a window to human nature. New York, NY: Penguin Books.

Feedback/Errata