3 Chapter 3: Pedagogical Leadership Theories – How do we situate these theories into our practices?

Learning Outcomes

- Influence commitment to the organization’s curricular philosophy

- Apply pedagogical leadership theories and practice to your decision-making in order to support a community of practice

Reflections on Leadership

In order to understand and apply the pedagogical theories we need to reflect on the term leadership for a while…

Leadership is a term used often – and often means different things to different people. There are so many approaches to leadership, so it’s important to examine our own ideas around and experience of leadership. Before we move too far ahead in this module, spend a bit of time reflecting on what leadership means to you. Also, consider what goals you have – or would like to set – for developing your own leadership skills.

For Reflection

How would you personally define leadership?

- Have you had an opportunity to lead others? If so, what were some positive aspects of the experience?

- What were some opportunities for growth that you would like to develop in the future?

- Think of someone you know, who you believe to be a good leader. What are some qualities and characteristics that you think makes them a good leader?

- How did interactions with this leader make you feel about yourself and your own skills and abilities?

- Think about someone you know who is or has been in a leadership role but who you believe doesn’t have good leadership skills. Why do you feel like they aren’t a good leader?

- How did interactions with this leader make you feel about yourself and your own skills and abilities?

- What are some things you have learned from these people that you can apply to your own growth as a leader? What are your own leadership goals?

- Do you feel that leadership skills have application outside of managing people in a work setting? If so, what are those applications?

Exercises in Developing Your Leadership Skills

“Great Leaders Create More Leaders Good leaders have vision and inspire others to help them turn vision into reality. Great leaders create more leaders, not followers. Great leaders have vision, share vision, and inspire others to create their own.” ~ Roy T. Bennett

This next section of the module is here for you to consider and explore your own leadership skill development. Consider some personal goals you might have as you work through this section of the module.

Developing Your Vision: A Personal Goal and Vision Planning Exercise

“You’ve got to think about big things while you’re doing small things so that all the small things go in the right direction.” ~ Alvin Toffler

Discovering Your Purpose

What gets you out of bed in the morning? What excites or moves you? What are your hopes and dreams for the future? What are some ideas that you hold close to your heart?

Feeling fulfilled often starts with asking big, deep questions. Your WHY is the bigger vision for what you want your life to be like, and how you want to feel.

At its best, exploring your why taps into uncovering the vision you have for your life. If you struggle in this process, that’s okay. When you keep your why in mind, you will at the very least choose some goals that are a little richer and more aligned with where you feel you want to go.

If the idea of finding your why is new or hard for you, we invite you to explore some bigger thoughts. Think of some foundational experiences in your life that made you who you are. What has motivated you to take this training? What are some things that inspire hope in you? What gives you a little spark of purpose?

You are the hero of your own life

Even though it might not feel like you’re a hero, you are! Think of a real-life hero, or even a favourite movie character or comic book character. All heroes have an origin story; most of the time we have some awareness of our hero’s origin story – the compelling and often difficult journey that shaped them.

Who did you think of? Why did you pick that person/character as a hero? What about their strengths, or character appeals to you? Do you see some of yourself in them?

Consider your own origin story

- You have been through some hard things. You’ve had some ah ha moments. Let’s tap into that.

- Can you think of a defining moment that made you decide to take this training?

- What are bits of your story that make you, YOU? (They can be good, or difficult experiences.)

- What was the hardest thing you had to overcome?

- Who supported you? Who are your allies and mentors?

- What are your superpowers (we all have superpowers/strengths)?

- How do you see all of this supporting your WHY?

- Spend some time over these next few weeks thinking about these things, and how all of them are connected to your WHY, or your sense of purpose.

Stay curious!

Identifying Your Strengths

In general, most people struggle with identifying personal strengths. Outside of a job interview when we are asked to identify our strengths, it can feel braggy, narcissistic or immodest.

But identifying personal strengths is essential to creating the life we want. We all have strengths, whether we see them or not. Discovering what they are and then building on them supports us to grow our character and our resiliency. Strengths aren’t static; they can shift and change, especially when we are intentional about developing them.

Owning our personal core strengths supports community and interconnection. When each of us are clear on what strengths we bring to the table, we can work together to be a stronger whole.

In the book Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification (Peterson & Seligman, 2004), the authors identify the following 24 character strengths:

- Integrity

- Enthusiasm

- Social Intelligence

- Appreciation of Beauty and Excellence

- Gratitude

- Optimism

- Humour

- Purpose

- Self-Control

- Prudence

- Humility

- Forgiveness

- Leadership

- Fairness

- Teamwork

- Perspective

- Love of Learning

- Open-mindedness

- Curiosity

- Creativity

- Bravery

- Perseverance

All of us have most of these character strengths, but some will be stronger or more developed in us than others.

- What are some strengths that you feel are missing from this list?

- What would you say are your top 3 strengths?

The Positivity Project website article Character Strengths (n.d.) states:

Character strengths aren’t about ignoring the negative. Instead, they help us overcome life’s inevitable adversities. For example, you can’t be brave without first feeling fear; you can’t show perseverance without first wanting to quit; you can’t show self-control without first being tempted to do something you know you shouldn’t.

Skills Inventory

Strengths are not the same as skills. People often use these terms interchangeably, but they are two different things.

Strengths = who you are.

Skills = what you can do.

Strengths are associated with character (e.g. focused, humorous, open-minded, kind), while skills are associated with our abilities. Some examples of skills include: cooking/culinary, carpentry, car repair and restoration, drawing, accounting, web design, etc.).

We can all build our skillset; we can learn to cook, rock climb, play guitar, or draw, and we can improve on those skillsets through practice. So many people discover new skill sets even later in life. Skill building is one of the key points within self-determination theory.

When goal or vision planning it is useful to be clear on your skills, knowing that you can and will continue to learn. Learning new skills is part of the magic of life. Skills are ever growing, and everyone starts off rough in the journey of learning to do something new. Skill development requires practice, attention, and time.

Food for thought…

- What are some of your skills?

- What are some skills you would like to develop?

| Source Cusick, J. (2022). Post-secondary peer support training curriculum. BCcampus. |

| This chapter contains material from Post-Secondary Peer Support Training Curriculum by Jenn Cusick. Used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. |

Apply pedagogical leadership theories and practice to your decision-making in order to support a community of practice

After you have reflected on your leadership and on your own leadership skills and strengths is time to dive deep into the theories that will guide a community of practice at your center.

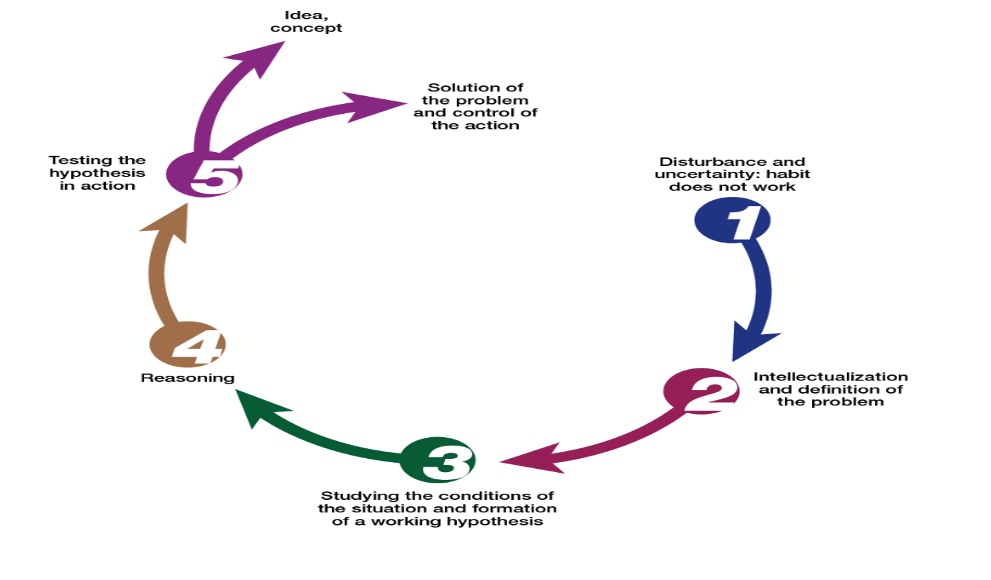

John Dewey Model

“We do not learn from experience. We learn from reflecting on experience.” ~ John Dewey (1933)

The fundamental theories and models of reflection and reflective practice were born initially from the work of Dewey and Schön. A century ago, John Dewey emphasized the importance of involving the learner in reflection. He believed that our experiences shape us, and when reflective practice is part of learning, meaning and relevancy is created, which initiates growth and change (Dewey, 1933).

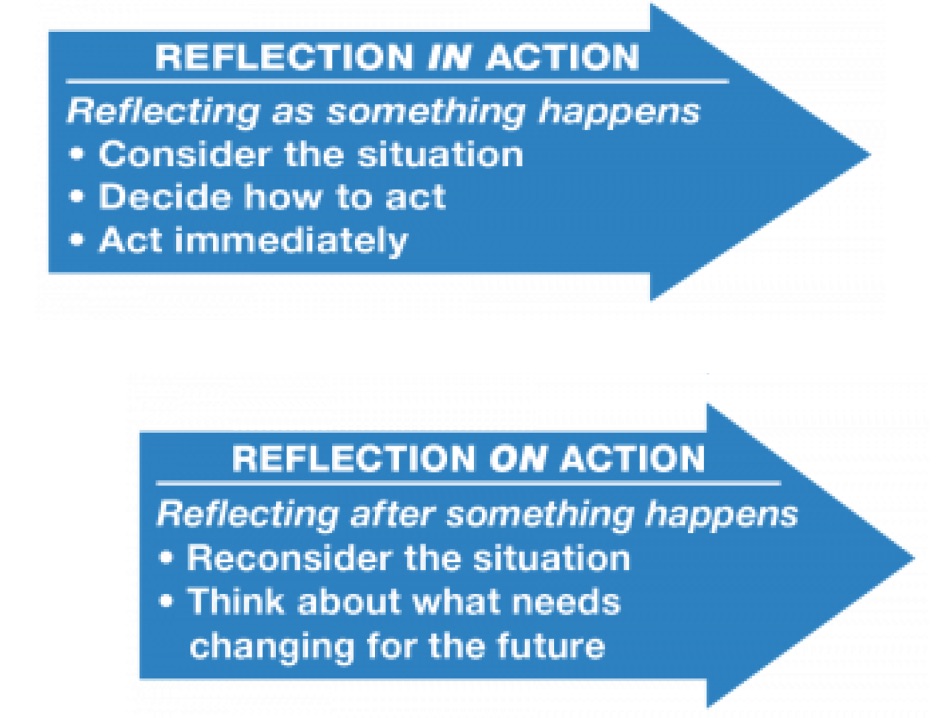

Schön Model

Schön (1983) based his work on that of Dewey and is most widely known for his theory of reflecting in and reflecting on one’s practice. His theory was grounded in reflection from a professional knowledge and learning perspective (Bolton, 2014, p.6). In simple terms this is described as reflecting as the experience is occurring or reflecting on the experience after it has occurred. Reflecting in action refers to situations such as: thinking on your feet, acting straight away, and thinking about what to do next. Reflecting on action means you are thinking about what you would do differently next time, taking time to process (Bolton, 2014, p.6).

| Sources Al-Amrani, S. N. (2021). Developing a framework for reviewing and designing courses in higher education: A case study of a post-graduate course at Sohar University. SSRN Electronic Journal. Bolton, G. (2014). Reflective practice: Writing and professional development(4th ed.). SAGE. Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Basic Books. |

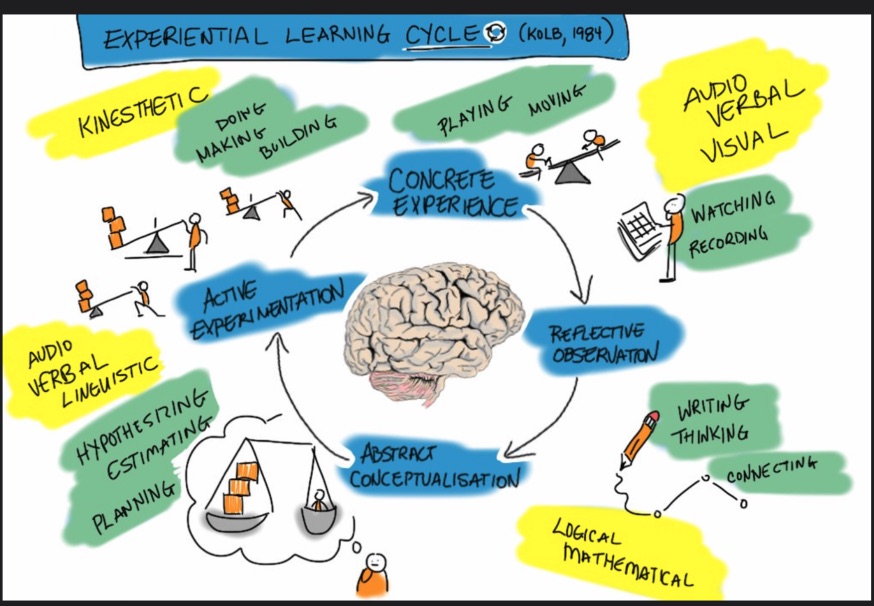

Kolb’s Model

Kolb’s model (1984) is based on theories about how people learn, this model centers on the concept of developing understanding through actual experiences and contains four key stages:

- Concrete experience

- Reflective observation

- Abstract conceptualization

- Active experimentation

The model argues that we start with an experience – either a repeat of something that has happened before or something completely new to us. The next stage involves us reflecting on the experience and noting anything about it which we haven’t come across before. We then start to develop new ideas as a result, for example when something unexpected has happened we try to work out why this might be. The final stage involves us applying our new ideas to different situations. This demonstrates learning as a direct result of our experiences and reflections. This model is similar to one used by small children when learning basic concepts such as hot and cold. They may touch something hot, be burned and be more cautious about touching something which could potentially hurt them in the future.

| Sources Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Prentice-Hall. |

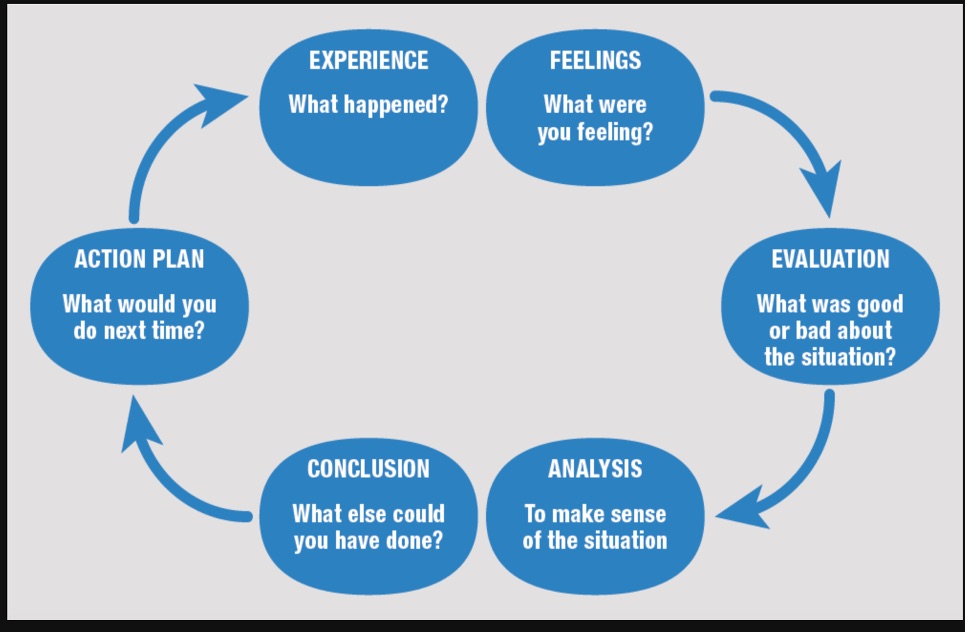

Gibbs Model

This model builds on the others and adds more stages. It is one of the more complex models of reflection, but it may be that you find having multiple stages of the process to guide you reassuring. Gibb’s cycle (1998) contains six stages:

- Experience

- Feelings

- Evaluation

- Analysis

- Conclusion

- Action plan

As with other models, Gibb’s begins with an outline of the experience being reflected on. It then encourages us to focus on our feelings about the experience, both during it and after. The next step involves evaluating the experience – what was good or bad about it from our point of view? We can then use this evaluation to analyze the situation and try to make sense of it. This analysis will result in a conclusion about what other actions (if any) we could have taken to reach a different outcome. The final stage involves building an action plan of steps which we can take the next time we find ourselves in a similar situation.

| Sources Gibbs, G. (1988). Learning by Doing: A Guide to Teaching and Learning Methods. Further Education Unit. |

| This chapter contains material from Reflective Practice in Early Years Education by Sheryl Third. Used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. |

Activity Time

After reviewing the theories and models, consider which one speaks to you. Complete a piece of writing using one theory or model process and explain if it helped or hindered your writing or reflective thinking.

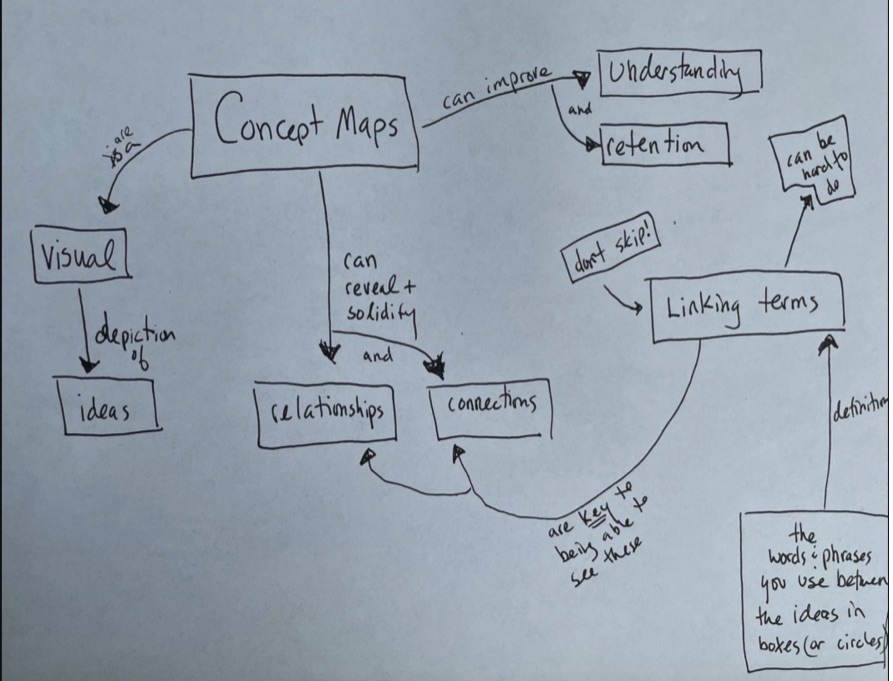

Please, also add a concept map or a mind map to illustrate your thoughts.

Please, write your reflection on a word document. You can use between 500-1000 words.

Sample Concept Maps:

Sample # 1:

Sample # 2: