3.2 The Digestive System

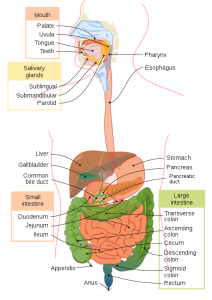

The function of the digestive system is to break down the foods you eat, release their nutrients, and then absorb those nutrients into the body. The small intestine, where the majority of digestion occurs and where most of the released nutrients are absorbed into the blood or lymph, is the workhorse of the system, but each of the digestive system organs also makes a vital contribution to this process. Figure 3.1 shows all the major components of the digestive system.

As is the case with all the body systems, the digestive system does not work in isolation—it functions cooperatively with the other systems of the body. Consider for example, the interrelationship between the digestive and cardiovascular systems. Arteries supply the digestive organs with oxygen and processed nutrients, and veins drain the digestive tract. These intestinal veins, which constitute the hepatic portal system, are unique because they do not return blood directly to the heart. Rather, the blood is diverted to the liver where its nutrients are offloaded for processing before the blood completes its circuit back to the heart. At the same time, the digestive system provides nutrients to the heart muscle and vascular tissues to support their functioning.

The interrelationship of the digestive and endocrine systems is also critical. Hormones secreted by several endocrine glands, as well as the endocrine cells of the pancreas, stomach, and small intestine, contribute to the control of digestion and nutrient metabolism. In turn, the digestive system provides the nutrients to fuel endocrine function. Table 3.1 below gives a brief overview of how these other systems contribute to the functioning of the digestive system.

Table. 3.1. Benefits of the Digestive System to Other Body Systems

| Body System | Benefits Received by the Digestive System |

|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | Blood supplies the digestive organs with oxygen and processed nutrients. |

| Endocrine | Endocrine hormones help regulate secretion in the digestive glands and accessory organs. |

| Integumentary | The skin helps protect the digestive organs and synthesizes vitamin D for calcium absorption. |

| Lymphatic | Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue and other lymphatic tissues defend against the entry of pathogens; lacteals (lymphatic capillaries) absorb lipids, and lymphatic vessels transport lipids to the bloodstream. |

| Muscular | The skeletal muscles support and protect the abdominal organs. |

| Nervous | Sensory and motor neurons help regulate secretions and muscle contractions in the digestive tract. |

| Respiratory | The respiratory organs provide oxygen and remove carbon dioxide. |

| Skeletal | The bones help protect and support the digestive organs. |

| Urinary | The kidneys convert vitamin D into its active form, allowing calcium absorption in the small intestine. |

The video below provides an overview of the digestive system and gives you a foundation of knowledge that you can use as you read through this chapter.

(DrBruce Forciea, 2015)

Digestive System Organs

The easiest way to understand the digestive system is to divide its organs into two main categories. The first category is the organs that make up the alimentary canal. Accessory digestive organs comprise the second group and are critical for orchestrating the breakdown of food and the assimilation of its nutrients into the body. The accessory digestive organs, despite their name, are critical to the functioning of the digestive system.

Alimentary Canal Organs

The alimentary canal, also called the gastrointestinal (GI) tract or gut, is a one-way tube about 7.62 metres (25 feet) long during life and closer to 10.67 metres (35 feet) in length when measured after death, once smooth muscle tone is lost. The main function of the organs of the alimentary canal is to nourish the body. This tube begins at the mouth and terminates at the anus. Between those two points, the canal is modified as the pharynx, esophagus, stomach, and small and large intestines to fit the functional needs of the body. Both the mouth and the anus are open to the external environment, so food and wastes within the alimentary canal are technically considered to be outside the body. Only through the process of absorption do the nutrients in food enter into and nourish the body’s “inner space.”

Accessory Structures

Each accessory digestive organ aids in the breakdown of food. Within the mouth, the teeth and tongue begin mechanical digestion while the salivary glands begin chemical digestion. Once food products enter the small intestine, the gallbladder, liver, and pancreas release secretions such as bile and enzymes that are essential for digestion to continue. Together, these are called accessory organs because they sprout from the lining cells of the developing gut (mucosa) and augment its function; indeed, you could not live without their vital contributions, and many significant diseases result from their malfunction. Even after their development is complete, they maintain a connection to the gut by way of ducts.

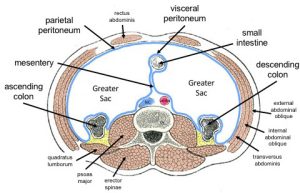

The Peritoneum

The digestive organs within the abdominal cavity are held in place by the peritoneum, a broad, serous membranous sac made up of squamous epithelial tissue surrounded by connective tissue. It is composed of two different regions: the parietal peritoneum, which lines the abdominal wall, and the visceral peritoneum, which envelops the abdominal organs (Fig. 3.2). The peritoneal cavity is the space bounded by the visceral and parietal peritoneal surfaces. A few millilitres of watery fluid act as a lubricant to minimize friction between the serosal surfaces of the peritoneum.

The digestive system uses mechanical and chemical activities to break food down into absorbable substances during its journey through the digestive system. Table 3.2 provides an overview of the basic functions of the digestive organs.

| Organ | Major Functions | Other Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Mouth |

|

|

| Pharynx |

|

|

| Esophagus |

|

|

| Stomach |

|

|

| Small intestine |

|

|

| Accessory organs |

|

|

| Large intestine |

|

|

Digestive Processes

The process of digestion includes six activities: ingestion, propulsion, mechanical or physical digestion, chemical digestion, absorption, and defecation.

The first of these, ingestion, refers to the entry of food into the alimentary canal through the mouth. There, the food is chewed and mixed with saliva, which contains enzymes that begin breaking down the carbohydrates in the food plus some lipid digestion via lingual lipase. Chewing increases the surface area of the food and allows an appropriately sized bolus to be produced.

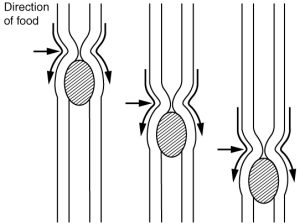

Food leaves the mouth when the tongue and pharyngeal muscles move it into the esophagus. This act of swallowing, the last voluntary act until defecation, is an example of propulsion, which refers to the movement of food through the digestive tract. It includes both the voluntary process of swallowing and the involuntary process of peristalsis. Peristalsis consists of sequential, alternating waves of contraction and relaxation of the alimentary wall smooth muscles, which act to propel food along (Fig. 3.3). These waves also play a role in mixing food with digestive juices. Peristalsis is so powerful that the foods and liquids you swallow enter your stomach even if you are standing on your head.

Digestion includes both mechanical and chemical processes. Mechanical digestion is a purely physical process that does not change the chemical nature of the food. Instead, it makes the food smaller to increase both surface area and mobility. It includes mastication, or chewing, as well as tongue movements that help break food into smaller bits and mix it with saliva. Although there may be a tendency to think that mechanical digestion is limited to the first steps of the digestive process, it occurs after the food leaves the mouth as well. The mechanical churning of food in the stomach serves to further break it apart and expose more of its surface area to digestive juices, creating an acidic “soup” called chyme. Segmentation, which occurs mainly in the small intestine, consists of localized contractions of the circular muscle of the muscularis layer of the alimentary canal. These contractions isolate small sections of the intestine, moving their contents back and forth while continuously subdividing, breaking up, and mixing the contents. By moving food back and forth in the intestinal lumen, segmentation mixes food with digestive juices and facilitates absorption.

In chemical digestion, which starts in the mouth, digestive secretions break down complex food molecules into their chemical building blocks (for example, proteins into separate amino acids). These secretions vary in composition, but typically contain water, various enzymes, acids, and salts. The process is completed in the small intestine.

Food that has been broken down is of no value to the body unless its nutrients enter the bloodstream and are put to work. This occurs through the process of absorption, which takes place primarily within the small intestine. There, most nutrients are absorbed from the lumen of the alimentary canal into the bloodstream through the epithelial cells that make up the mucosa. Lipids are absorbed into lacteals and are transported via the lymphatic vessels to the bloodstream (the subclavian veins near the heart).

In defecation, the final step in digestion, undigested materials are removed from the body as feces. In some cases, a single organ is in charge of a digestive process. For example, ingestion occurs only in the mouth and defecation only in the anus. However, most digestive processes involve the interaction of several organs and occur gradually as food moves through the alimentary canal; see Fig. 3.4 for more detail on the functions of the organs involved in digestion.

The following video gives an a overview of how the digestive system works and provides a great summary of the content you have learned so far in this chapter.

(Bryce, 2017)

Attribution

Unless otherwise indicated, material on this page has been adapted from the following resource:

Betts, J. G., Young, K. A., Wise, J. A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D. H., Korol, O., Johnson, J. E., Womble, M., & DeSaix, P. (2013). Anatomy and physiology. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/details/books/anatomy-and-physiology, licensed under CC BY 4.0

References

Bryce, E. (2017, December 14). How your digestive system works – Emma Bryce [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/Og5xAdC8EU

DrBruce Forciea. (2015, March 18). Anatomy and physiology of the digestive system [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/1ssJV-EpfiQ. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

Image Credits (images are listed in order of appearance)

Digestive system diagram en by LadyofHats, Public domain

General Distribution of the Peritoneum by Dennis M DePace, PhD, CC BY-SA 4.0

2404 PeristalsisN by OpenStax College, CC BY 3.0

2405 Digestive Process by OpenStax College, CC BY 3.0

entry of food into the alimentary canal through the mouth

the movement of food through the digestive tract

the contraction and relaxation of muscles that move in a wave down a tube, for example, in the intestines

the purely physical process of breaking food down

chewing

when digestive secretions break down complex food molecules into their chemical building blocks

when food that is broken down enters the bloodstream and its nutrients are put to work

when undigested materials are removed from the body as feces