8 Chapter 8: Radio, Podcasts and Television

Amanda Williams

Introduction

From the early days of experimental radio transmissions in the 1920s to the complex media ecosystem of the 21st century, broadcast media have profoundly shaped how people access news, entertainment, and cultural content. In Canada, radio and television have not only served as key vehicles for information dissemination and national storytelling but have also played a vital role in shaping Canadian identity, regional connections, and public discourse. Over time, these platforms evolved through a series of technological innovations, from AM to FM radio, from black-and-white to colour television, and eventually to cable and satellite services, each phase altering how audiences engaged with content.

These developments are part of the broader Electronic Revolution, a period marked by the rise of mass communication technologies.

Alongside these technological developments, the Canadian broadcasting landscape has been shaped by a unique regulatory environment to protect Canadian content and promote cultural sovereignty in a market heavily influenced by American media. Institutions such as the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) have played a pivotal role in managing this balance, influencing everything from ownership structures to programming requirements.

Today, traditional broadcast models are facing transformative pressures. The rise of digital streaming platforms, on-demand video services, and the rapid growth of podcasting are reshaping how content is created, distributed, and consumed, showing overlap between the Electronic and Digital Revolutions (which will be further explored in the following chapter). These shifts raise important questions about the future of public broadcasting, the role of media regulation, and the sustainability of Canadian content in an increasingly globalized and algorithm-driven media environment.

This chapter explores the historical trajectory of radio and television in Canada, tracing technological advancements, institutional developments, and cultural impact. It also examines how the current convergence of traditional and digital media forms is redefining the boundaries of broadcast communication. By understanding where broadcast media came from and how they have adapted over time, we can more effectively analyze the industry’s challenges today and anticipate the directions it may take in the years ahead.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Identify and describe the early development of radio, television, and podcasts globally and in Canada, and assess their current relevance.

- Analyze the role of government regulation in shaping broadcast and audio media, including emerging frameworks for podcasting.

- Evaluate the effectiveness of Canadian content regulations in promoting national culture across traditional broadcast and digital audio platforms.

- Assess the impact of technological innovations on the production, distribution, and consumption of broadcast media and podcasts. Examine how broadcast media and podcasting have adapted to digital disruption and changing audience behaviours.

The Global History of Radio

Global Radio Development (1880s-1930s)

The evolution of radio was not the work of a single inventor or nation, but rather the result of interconnected scientific breakthroughs and industrial innovation across multiple countries. Guglielmo Marconi, often recognized as the father of modern radio, built upon the discoveries of German physicist Heinrich Hertz, who demonstrated the existence of electromagnetic waves, and incorporated the work of others such as Nikola Tesla and Alexander Popov (Hong, 2001; Nahin, 2001). Marconi’s key contribution was transforming theoretical ideas into working systems. His company, the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company, quickly developed and sold wireless technology, installing systems on ships and coastal stations (Coe, 1996).

While Marconi concentrated on long-distance wireless telegraphy, Reginald Fessenden (a Canadian Pioneer) focused on transmitting audio signals. His 1906 Christmas Eve transmission demonstrated that voice and music could be sent wirelessly, marking a significant step in developing radio as a cultural and entertainment medium beyond military or industrial use (Grant, 1907).

As radio technology advanced, governments began regulating its growing influence. Radio became essential for military communication, espionage, and naval coordination during World War I. Countries introduced systems to manage frequencies and avoid interference. The Radio Act of 1927 created the Federal Radio Commission in the United States, while similar regulatory bodies were established in Canada, the United Kingdom, Germany, and France (McChesney, 1992).

International Broadcasting Models (1920s-1930s)

By the 1930s, radio had evolved into a widely used mass medium with distinct national approaches. In Europe, the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), reorganized under a Royal Charter in 1927, pioneered a publicly funded, non-commercial broadcasting model with a mission to inform, educate, and entertain (Briggs & Burke, 2005; Hendy, 2007). This model influenced public broadcasting systems worldwide.

In contrast, the United States saw the rapid expansion of commercial radio networks such as the National Broadcasting Company (NBC) and the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS), which relied on advertising revenue and audience ratings to shape programming (Sterling & Kittross, 2002). These networks helped entrench radio as a central element of American culture through entertainment, serialized drama, and news.

Globally, radio served diverse political and cultural functions. Authoritarian regimes in fascist Italy and Nazi Germany used radio as a propaganda tool to spread nationalist ideologies and mobilize public support (McLellan, 2011; Mosse, 2003). Meanwhile, in democratic societies, radio supported public discourse and cultural cohesion, promoting national identity and civic participation (Sterling & Kittross, 2002).

The Golden Age of Radio in the United States (1930s-1950s)

The Golden Age of Radio in the United States, from the early 1930s through the mid-1950s, represents a foundational era in mass communication. Emerging during the Great Depression, radio became vital for millions of Americans through shared auditory experiences. The economic hardships made costly entertainment largely inaccessible. At the same time, radio’s affordability, requiring only a one-time receiver purchase, established it as both entertainment and a critical lifeline providing news, comfort, and community during uncertain times.

Radio’s fixed broadcasting schedule distinguished it from print media, creating shared temporal rhythms where families gathered to listen. Popular programs like The Jack Benny Program provided comedy relief, while soap operas like Guiding Light captivated audiences with serialized storytelling. Weekly dramas such as The Shadow transported listeners into thrilling adventures through purely auditory means. These programs created cultural common ground, reinforcing radio’s power as a unifying social force (Hilmes, 2013).

Radio personalities became trusted companions and celebrities, fostering intimate connections between broadcasters and listeners. Whether Edward R. Murrow reporting on World War II or announcers narrating dramatic shows, radio established unique relationships of trust and immediacy, often shaping public opinion and national identity (Hilmes, 2013).

Radio in Canada

Early Canadian Radio Development (1900s-1920s)

Before the 1920s, Canadian society relied heavily on newspapers as the primary medium for news and public discourse. Early radio suggested the possibility of real-time communication accessible to non-literate audiences, foreshadowing a dramatic shift in media use and accessibility (Vipond, 2000).

Canada played a significant role in early radio history, particularly with Marconi’s 1901 transatlantic transmission from Cornwall, England, to Newfoundland, marking a breakthrough in global communication (Douglas, 1987). The Canadian government granted Marconi $80,000 to continue his experiments, making Canada one of the first states to support wireless technology.

“1906-07” by ITU Pictures is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

As noted, Canadian inventor Reginald Fessenden pioneered voice transmission, developing continuous-wave transmission and amplitude modulation (AM). His December 24, 1906, Christmas Eve broadcast from Brant Rock, Massachusetts, including music and Bible readings, is widely regarded as the first radio broadcast intended for public reception (Babe, 2000).

Initially, wireless technology in Canada was primarily used in maritime and military contexts. Ships communicated with coastal stations for safety and weather updates, with wireless proving critical during disasters like the sinking of the Titanic in 1912 (Sterling & Kittross, 2002). Canadian interest in radio as mass communication grew rapidly after World War I, culminating in a uniquely Canadian broadcasting landscape influenced by British public broadcasting models and American commercial practices (Briggs & Burke, 2005; Douglas, 1987).

The Canadian National Railway and Broadcasting Innovation (1920s)

Among the most innovative early adopters was the Canadian National Railway (CNR), which recognized radio as a multifaceted platform for brand development, passenger engagement, and national integration. Under President Sir Henry Thornton’s visionary leadership, the CNR saw broadcasting as a means to unite Canadians across vast distances while promoting railway services (Raboy, 1990).

Beginning in the early 1920s, the CNR built one of the first national radio networks worldwide. The company owned three stations (Vancouver, Ottawa, Montreal) and leased airtime on seven additional private stations strategically located across the country. Programming was diverse and bilingual, featuring classical and popular music, dramatic theatre, lectures, and educational programs appealing to urban and rural listeners, often featuring local artists, teachers, and musicians (Raboy, 1990).

The CNR’s most innovative contribution was developing “phantom stations”—part-time operations airing pre-recorded or networked content for two to three hours weekly, typically coinciding with train arrivals or departures. By 1922, the company had created 18 phantom stations targeting smaller towns and rural areas along railway lines, ensuring national programming access regardless of geography. This integrated strategy linked physical infrastructure with Canada’s emerging media landscape, using radio to bridge geographic, linguistic, and cultural divides (Raboy, 1990).

Regulation and the Birth of Public Broadcasting (1928-1936)

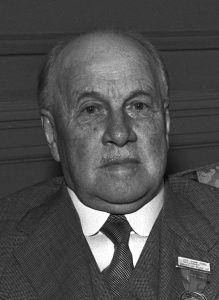

By the late 1920s, concerns about Canadian radio’s future intensified. The rapid proliferation of private stations relying heavily on American programming raised fears about U.S. cultural influence overshadowing Canadian voices (Raboy, 1990; Vipond, 1992). In response, the federal government appointed the Royal Commission on Radio Broadcasting in 1928, chaired by Sir John Aird.

The Aird Commission’s 1929 report recommended establishing a national, publicly owned broadcasting entity responsible for operating all Canadian stations, emphasizing that radio must serve the public interest rather than commercial or foreign agendas (Aird Commission, 1929). Inspired by the BBC model, reformers Graham Spry and Alan Plaunt formed the Canadian Radio League in 1930, advocating for implementing the Aird Report’s recommendations. Spry framed the situation as “the state or the United States” (Raboy, 1990; Vipond, 1992).

This activism led to the formation of the Canadian Radio Broadcasting Commission (CRBC) on May 26, 1932. As Canada’s first national broadcasting agency, the CRBC had dual mandates: producing Canadian content and regulating the industry. Commercial content was limited to 5% of programming to prevent American-style commercialization.

However, the CRBC faced funding and political challenges. In 1936, Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King’s Liberal government dissolved the CRBC, creating the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) as a Crown corporation through the Canadian Broadcasting Act. Unlike its predecessor, the CBC had a more stable organizational structure and dedicated funding through license fees paid by radio set owners (Armstrong, 2016).

CBC Development and Television Era (1936-1970s)

The CBC’s establishment marked a turning point in Canadian media history. It provided a national platform for Canadian culture, language, and identity. While continuing to rebroadcast popular American programs, the CBC increasingly invested in original Canadian programming, including news, drama, music, and public affairs (Armstrong, 2016; Raboy, 1990).

In its early years, CBC/Radio-Canada expanded its reach and developed Canadian content, producing popular shows such as The Happy Gang, Just Mary, and Hockey Night in Canada. During World War II, it launched an overseas service. It created an independent news service known for integrity, with news anchors including Charles Jennings and Lorne Greene, known as the “Voice of Doom” for wartime broadcasts (Eaman et al., 2024).

Television broadcasting began in 1952, first in Montreal (CBFT) and Toronto (CBLT). Initially reaching just over a quarter of the population, CBC television quickly expanded to 60% by 1954, continuing through the 1950s and 60s, bringing Canadian-produced content nationwide and reducing dependence on American programming (Eaman et al., 2024).

The 1970s marked a significant transformation in CBC Radio through internal review, leading to renewed focus on current affairs and Canadian content. FM radio was developed for high-quality music, drama, and arts programming. Landmark shows such as As It Happens, The Vinyl Café, and The Current helped define CBC Radio’s distinct identity (Eaman et al., 2024).

The Golden Age of Canadian Radio (1927-1952)

Canada’s Golden Age of Radio officially commenced in 1927 with the first radio drama broadcast by the CNRV Players over the CNR network. It lasted until roughly 1952, when television began competing for public attention. Radio became a powerful cultural institution throughout these decades, contributing significantly to constructing a distinct Canadian identity during a time of substantial American media influence.

Radio receivers were often elegant furniture pieces housed in finely crafted wooden cabinets, elevating radio to a symbol of modernity and sophistication. Families gathered around radios at scheduled times for collective listening. This became a shared social ritual that facilitated community and belonging and strengthened familial and communal bonds, especially in rural or remote areas (Gasher et al., 2016).

The content was instrumental in helping Canadians imagine and assert national identity. Unlike print media or early cinema, which were often imported or heavily influenced by American culture, Canadian radio broadcasters sought programming reflecting Canadian values, stories, and concerns. This deliberate cultural project aimed to cultivate a uniquely Canadian narrative uniting a geographically vast and culturally diverse population.

In rural and isolated communities, where newspapers were often infrequent and television nonexistent, radio was a vital link to the broader world, helping mitigate social isolation and foster belonging to a national community. Evening news programs, serialized dramas, and shared listening experiences formed a public sphere where people discussed current events and cultural phenomena, reinforcing national consciousness through everyday rituals and media consumption habits (Hilmes, 2013; Gasher et al., 2016).

Educational Broadcasting Pioneers (1925-present)

Canada pioneered educational broadcasting in 1925 when the University of Alberta’s Department of Extension started using radio to disseminate educational content, collaborating with CJCA to air lectures, music programs, and public service content. This innovative approach overcame geographic barriers, providing learning opportunities to remote and rural areas with limited access to formal education.

By 1927, the University of Alberta launched CKUA, Canada’s first dedicated educational broadcaster. CKUA’s programming featured original radio plays, lectures, music recitals, and cultural programming designed for diverse audiences, including schools, community organizations, and isolated rural populations. To extend access, CKUA loaned radio sets to classrooms and communities that could not afford their own (Gasher et al., 2016).

Sheila Marryat, CKUA’s general manager in the 1930s, was pivotal in shaping educational broadcasting’s direction, emphasizing radio as a public good serving educational and cultural enrichment. Her expertise later became invaluable to the CBC when developing national educational programming in the late 1930s. CKUA’s legacy endures today as a publicly supported broadcaster focused on arts, culture, and education, demonstrating broadcast media’s enduring potential as a tool for social and cultural development in Canada.

The National Farm Radio Forum: Community Education Through Broadcasting (1941-1965)

One of the most innovative and successful educational broadcasting initiatives in Canadian history was the National Farm Radio Forum, which operated from 1941 to 1965. This groundbreaking program represented a unique partnership between the Canadian Association for Adult Education (CAAE), the Canadian Federation of Agriculture (CFA), and the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC), demonstrating how radio could serve as a powerful tool for community education and democratic participation.

The Farm Radio Forum operated on a distinctive model that went far beyond traditional broadcasting. Each week from November to March, the CBC aired half-hour radio programs on Monday nights that addressed issues relevant to rural communities, including agricultural practices, farm finances, health care, education, and social concerns. However, the program’s real innovation lay in its interactive structure: rural communities across Canada formed local listening groups that would gather in neighbors’ homes to listen collectively to the broadcast, then engage in guided discussions using printed materials and prepared questions mailed to them in advance.

The program’s motto, “Read, Listen, Discuss, Act,” encapsulated its philosophy of combining media consumption with active community engagement and practical action. Topics covered ranged from wartime issues like farm labor shortages during World War II to broader social questions such as “Farm Women in Public Life” and “The Teacher in the Community.” The broadcasts used various formats, including panel discussions, interviews, speeches, and radio dramas featuring characters from the fictional Sunnybridge Farm (Faris, 1975).

At its peak in 1949, the National Farm Radio Forum boasted over 1,600 registered listening groups across Canada with more than 21,000 active participants. Each weekly broadcast included a five-minute summary of discussions from local forums across the provinces from the previous week, creating a national dialogue that connected rural communities from coast to coast. Highlights of farmers’ feedback were often shared with provincial ministers of agriculture and education, and even with federal ministers, giving rural voices direct access to policymakers.

The program’s success extended beyond Canada’s borders. UNESCO commissioned a study of the Farm Radio Forum in 1952, which resulted in a detailed and complimentary report published in 1954. The Canadian model inspired similar community listening programs in countries including India, Ghana, and France. In 2009, the Forum was designated as a National Historic Event for “pioneering interactive distance education.”

However, as Canadian agriculture transformed in the post-war era, with small-scale farming giving way to large-scale agribusiness and rural populations declining, participation in Farm Radio Forum began to decrease after 1949. The number of groups fell by approximately 100-150 annually, reaching around 500 in 1958 and just 230 by the program’s final year. The National Farm Radio Forum aired its last broadcast on April 30, 1965, but its legacy lived on through the formation of Farm Radio International in 1979, which continues to use similar community-based radio education models in developing countries worldwide.

Radio’s Adaptation to Television and FM (1950s-present)

The emergence of television broadcasting in the 1950s represented a dramatic shift in the media landscape, fundamentally challenging radio’s dominance as the primary mass communication medium. Iconic radio programs like Dragnet, The Lone Ranger, and Amos’n’ Andy successfully transitioned to television, leveraging the new medium’s visual storytelling capabilities. This migration of popular content created a significant void in radio’s programming, compelling radio broadcasters to rethink and redefine their purpose to survive in an increasingly competitive environment.

Adaptation became crucial for radio’s survival. The medium evolved from being a general-purpose source of entertainment and information to a more specialized platform focused primarily on music, talk shows, news, and formats that capitalized on its inherent strengths—portability and immediacy. Radio became an ideal companion for the burgeoning car culture of the post-war era; by the late 1950s and early 1960s, radios installed in automobiles transformed listening into a mobile and personalized experience, allowing audiences to engage with content while on the move. This transformation helped radio maintain cultural relevance, carving out a niche distinct from television’s stationary and visual nature.

Regulatory frameworks were crucial in shaping radio’s evolution, especially in Canada. The Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) actively intervened to manage the development of AM and FM radio services, aiming to promote diversity and prevent market saturation. Initially, FM radio was subject to stringent content rules to differentiate it from the more established AM stations. FM was encouraged to focus on educational, cultural, and specialized programming rather than popular music, reflecting its experimental and public-service origins. However, those restrictions gradually eased as FM’s superior sound quality became widely recognized. By the 1970s, FM radio emerged as the dominant platform for music broadcasting, especially genres like rock, jazz, and classical, capitalizing on its clear and high-fidelity audio (Lorimer & Gasher, 2004).

Despite these changes, radio retained its unique qualities as an intimate, one-to-many communication medium. Unlike television, which often demands visual attention and is consumed socially or communally, radio remained personal and auditory, able to accompany listeners in private moments or everyday activities. This personal connection helped radio endure through multiple technological shifts.

In the digital age, radio has further adapted by integrating with new platforms such as social media and streaming services to foster interaction and maintain listener engagement. Contemporary broadcasters use social media to create communities around shows, encourage audience participation, and expand their reach beyond traditional airwaves. This digital convergence ensures that radio continues to be a relevant and dynamic form of communication, combining its historic strengths with the possibilities of modern technology (Taras, 2015).

The Rise and Resonance of Podcasting: From Audioblogging to Global Media Phenomenon (Early 2000s-Present)

Building on radio’s tradition of intimate audio storytelling and leveraging the same digital technologies that enabled radio’s online evolution, podcasting emerged as a distinct medium that would fundamentally reshape audio consumption patterns.

Podcasting emerged in the early 2000s due to technological convergence and user innovation. Its origins lie in integrating audio files into RSS (Really Simple Syndication) feeds, a system developed by software pioneer Dave Winer. This innovation enabled automatic downloading and updating of digital audio content, a practice initially known as “audioblogging” (Taras, 2015). Around the same time, former MTV VJ Adam Curry collaborated with Winer to create the iPodder client, software that allowed users to subscribe to these audio feeds and sync new episodes directly to portable media players, especially Apple’s iPod. This process laid the technical foundation for the new medium and gave podcasting its name, combining “iPod” and “broadcast” (Bottomley, 2015).

Podcasting entered public awareness between 2004 and 2005. Curry’s podcast, Daily Source Code, showcased early experimentation with audio content, tone, and listener engagement, drawing attention to the medium’s grassroots potential. A pivotal moment came in June 2005 when Apple integrated podcast support into iTunes 4.9. This move dramatically increased the accessibility of podcasting, allowing users to discover, subscribe to, and listen to shows without technical expertise. It marked a democratizing shift in media production and distribution, enabling ordinary users—not just broadcasters or journalists—to create and share audio content (Taras, 2015; Bottomley, 2015).

From 2005 to 2013, podcasting experienced steady, if modest, growth. During this period, the medium faced significant challenges, including limited monetization strategies, competition from visually oriented platforms like YouTube, and branding confusion linked to the declining popularity of the iPod. Nevertheless, a vibrant ecosystem of independent creators and committed listeners persisted. Podcasters frequently used the format to engage with niche or underserved communities and to explore issues often overlooked by mainstream media (Wagman & Urquhart, 2012). This ability to address specialized interests became one of podcasting’s defining characteristics.

A cultural breakthrough occurred in 2014 with the launch of Serial, a true-crime podcast hosted by journalist Sarah Koenig and produced by the creators of This American Life. Serial attracted millions of listeners and helped redefine podcasting as a legitimate space for long-form, investigative storytelling. Its success marked the beginning of what scholars have called the “golden age of podcasting” (Bottomley, 2015). From 2014 to 2018, mainstream media companies, academic institutions, and commercial brands increasingly invested in podcast production, drawn by the medium’s capacity to build deep listener engagement and foster loyal communities.

Since 2018, podcasting has entered a rapid commercial expansion and professionalization phase. Major technology companies like Spotify, Apple, and Amazon have acquired exclusive shows, production studios, and analytics platforms to consolidate their presence in the audio streaming market. These developments have introduced new business models, including subscriptions, branded partnerships, and listener-supported crowdfunding, and have made podcasts more discoverable through algorithm-driven recommendation systems (Berry, 2016).

Despite this expansion, podcasts remain distinct from traditional broadcast radio in several ways. First, they are delivered on-demand rather than through scheduled live programming, giving users unprecedented control over what and when they listen. Second, they are often portable and optimized for consumption on mobile devices, enabling listening during commuting, exercise, or household chores. Third, they frequently focus on highly specialized topics, from Indigenous storytelling and LGBTQ+ health to climate activism or niche fandoms, allowing for personalization and diversity not typically available in mainstream media.

From a formal standpoint, podcasts feature more polished post-production editing than live radio and are often structured around a conversational, intimate tone. Many podcasts use first-person narration, slow pacing, and narrative arcs that draw listeners into a sustained and emotionally engaging experience. Listening through headphones creates the sonic illusion of a private, one-on-one conversation between host and listener. Over time, recurring hosts and serialized formats build familiarity, trust, and emotional resonance. This sense of intimacy is further reinforced by parasocial relationships, in which listeners feel personally connected to hosts they have never met, and by the interactivity offered through social media platforms, listener feedback, and online communities (Berry, 2016; Llinares, Fox, & Berry, 2018).

As podcasts become more integrated into large-scale digital ecosystems, new questions emerge about how the medium’s foundational qualities might shift. Does algorithmic discovery promote a narrow range of content, or help audiences find shows that reflect their values and interests? How do advertising models, platform exclusivity, and standardized production expectations affect the creativity and intimacy that once defined independent podcasting? Can podcasts scale commercially without losing the trust and emotional depth that make them meaningful to listeners?

Podcasting exemplifies the convergence of traditional broadcast practices with digital interactivity, user-driven customization, and grassroots creativity. Its low barriers to entry, flexible formats, and global distribution continue to make it one of the most accessible and dynamic forms of contemporary media. At the same time, its evolution raises essential questions about what it means for a medium to grow while remaining personal and whether intimacy and scale can coexist in the digital attention economy.

The Global History of Television (Late 19th Century-Present)

As podcasting demonstrated the continued evolution of audio media in the digital age, television’s development followed a parallel but distinct trajectory, fundamentally reshaping visual communication and entertainment consumption worldwide.

The history of television is a complex story of technological innovation, cultural transformation, and regulatory evolution that has unfolded over more than a century. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, television technology emerged from early experimental systems aimed at transmitting moving images over distances. Mechanical systems, such as those developed by Paul Nipkow in the 1880s, laid the groundwork, but the transition to electronic television in the 1920s and 1930s marked a turning point. Inventors like John Logie Baird in the United Kingdom and Philo Farnsworth in the United States made significant contributions, developing the first practical systems for scanning and displaying moving images electronically (Abramson, 2003).

The invention of the cathode ray tube (CRT) as a display technology was critical to developing television as a mass medium. By the late 1930s, several countries began experimental broadcasts, including the UK, Germany, and the U.S. However, the outbreak of World War II stalled commercial expansion as resources were redirected to the war effort (Spigel, 1992). After the war, television entered a period of rapid growth and cultural influence, especially in North America and Western Europe. The 1950s saw television become a central feature of daily life, reshaping entertainment, news consumption, and advertising practices. Television sets became more affordable and widespread, turning the medium into a dominant form of mass communication (Boddy, 1990).

Culturally, television profoundly shaped social norms and public discourse. In the United States, the “Golden Age of Television” brought live dramatic productions that challenged and reflected contemporary social issues (Spigel, 1992). Meanwhile, public broadcasters like the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) prioritized educational and cultural programming, emphasizing public service mandates over commercial interests (Scannell & Cardiff, 1991). Different countries adapted television to their political and social contexts. Authoritarian regimes often used television as a propaganda tool, while democratic nations balanced commercial entertainment with regulatory efforts to ensure diverse, locally relevant content (Miller et al., 2016).

Technological advancements throughout the latter half of the 20th century further transformed television. The transition to colour broadcasting in the 1960s added a new dimension to the viewer experience and expanded creative possibilities for producers (Boddy, 1990). The rise of satellite and cable television in the 1970s and 1980s significantly increased channel capacity and viewer choice, enabling the emergence of niche programming and international content distribution. This globalization of television programming led to the widespread export of Western television shows, particularly American ones, raising concerns about cultural imperialism and the erosion of local identities (Miller et al., 2016).

Governments worldwide responded to these challenges by establishing regulatory bodies managing content standards, ownership, and cultural protection. In the UK, the Independent Television Authority regulated commercial broadcasting, while in Canada, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) was created to safeguard Canadian cultural expression through policies such as Canadian content quotas (Fremeth, 2015; Raboy, 1990). These regulatory frameworks aimed to balance the benefits of commercial growth with the need to support domestic production and protect cultural sovereignty in the face of expanding global media markets.

Entering the digital age, television experienced yet another transformation. The switch from analog to digital broadcasting, which occurred in Canada between 2007 and 2011, improved picture quality and spectrum efficiency. More significantly, the advent of the internet and broadband connectivity facilitated the rise of streaming platforms such as Netflix, Hulu, and Amazon Prime Video. These services disrupted traditional broadcasting by offering on-demand viewing, greater interactivity, and wider content choices. This shift democratized content creation and consumption but also complicated regulatory oversight, especially regarding cultural preservation and equitable access (Lobato, 2019).

Against this global backdrop, the Canadian television landscape presents a unique case. Canada’s cultural diversity, bilingual nature, and proximity to the dominant American media market have shaped its television history in distinct ways. Canadian broadcasters and policymakers have continuously negotiated these pressures by fostering a strong public broadcaster in the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) and implementing regulatory measures through the CRTC to promote Canadian content and cultural expression (Fremeth, 2015). This ongoing balancing act reflects broader global tensions between technological innovation, globalization, and the protection of national cultural identity.

Phases of Canadian Television Development (1930s-Present)

Canadian television’s development reflects the country’s unique cultural, political, and geographic challenges. It navigates the pressures of proximity to the dominant U.S. media market and the need to cultivate a distinct national identity. Fremeth (2015) organizes Canadian television history into four phases, illustrating how technological innovations, cultural dynamics, and policy frameworks interacted over time.

The first phase, from the 1930s until 1952, was marked by experimentation and dependency. Due to technological and economic constraints, Canadian engineers and broadcasters explored television technology but relied heavily on American equipment, programs, and broadcast models. This early period witnessed concern that Canada’s cultural sovereignty was threatened by the overwhelming influence of U.S. media, especially given the shared language and close economic ties (Fremeth, 2015). These concerns led to calls for a national broadcasting policy to preserve Canadian culture and offer a Canadian voice.

The second phase, beginning with establishing the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s (CBC) television service in 1952 and extending into the 1960s, saw the institutionalization of public broadcasting. The CBC was mandated to foster Canadian culture and counterbalance American influence by producing and distributing Canadian programming. During this phase, government investments built infrastructure to expand the reach of television signals across Canada’s vast and often remote regions. Regulations emerged to promote Canadian content, nurturing homegrown talent in news, drama, and children’s programming. This period established television as a key platform for nation-building and cultural expression (Fremeth, 2015).

The third phase was characterized by commercialization and diversification from the 1970s through the 1980s. The Canadian television landscape opened to private broadcasters, specialty channels, and the arrival of cable television, dramatically increasing the number and types of available programs. Technological advancements such as colour broadcasts and satellite distribution extended reach and quality. Canadian policymakers faced the complex challenge of fostering a competitive market while protecting cultural priorities. The government introduced Canadian content quotas, funding programs such as the Canadian Television Fund, and supported French-language and Indigenous broadcasters to reflect the country’s multicultural and bilingual identity (Fremeth, 2015). This period broadened television’s role as a business and a cultural institution.

The fourth and ongoing phase began in the 1990s with the rise of digital technologies. The proliferation of the internet, mobile devices, and streaming services like Netflix, Crave, and Amazon Prime Video has disrupted traditional broadcasting models and viewer habits. Canadian regulatory bodies, such as the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC), have continually revised policies to maintain Canadian cultural presence amidst global competition, including regulations on digital platforms and funding for Canadian production (Fremeth, 2015; Lobato, 2019). This phase emphasizes multi-platform content delivery, interactive engagement, and innovation efforts within a rapidly shifting technological and economic environment. Canadian television continues to balance cultural protectionism with the realities of globalization and market liberalization, striving to keep a distinctly Canadian voice alive in the digital age.

Together, these phases highlight the ongoing negotiation between technology, culture, and policy in shaping Canadian television’s evolution, reflecting broader national goals of identity, inclusion, and sovereignty.

Canadian Content Regulations (1949-Present)

Concern over the overwhelming influence of American cultural products on Canadian audiences motivated the federal government to take decisive action to protect and promote Canadian culture through broadcasting. Two key Royal Commissions played a foundational role in this process. The 1949 Massey Commission highlighted the need for federal support of cultural institutions and the arts, leading to the creation of the National Library of Canada and the Canadian Council for the Arts to foster Canadian cultural development. Building on this, the 1955 Fowler Commission recommended establishing minimum cultural standards for private broadcasters and creating an independent regulatory body to oversee broadcasting. These recommendations eventually culminated in the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) (Litt, 2012).

The introduction of Canadian Content regulations, known colloquially as CanCon, was a central strategy designed to ensure that Canadian voices and stories would be visible and audible amid the flood of American media content. The first CanCon requirements were introduced in 1958, requiring that private television stations dedicate a significant portion of their programming to Canadian-produced content. Historically, this included a requirement for private broadcasters to air 60% Canadian content overall between 6 AM and midnight, with at least 50% during the prime evening hours from 6 PM to midnight. Public broadcaster CBC was held to similar standards, expected to maintain at least 60% Canadian programming in its schedule. These quotas reflected a government commitment to cultural sovereignty through media regulation, positioning CanCon as a cornerstone of the Broadcasting Act (Canada, 1991).

In 2011, the overall requirement for Canadian content was adjusted to 55%, reflecting changing market conditions and challenges faced by broadcasters. Nonetheless, CanCon’s core intent remains steadfast: to support the production, distribution, and visibility of Canadian stories, talent, and cultural expression in a media environment heavily influenced by American programming.

The CRTC certifies programs as Canadian based on a points system that evaluates the producer’s nationality and key creative personnel, such as writers, directors, and lead performers. Additionally, a minimum percentage of production expenses must be incurred in Canada with Canadian companies and talent providing those services. This rigorous certification process ensures that content labelled as Canadian genuinely reflects Canadian creative and economic involvement (Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission, 2015).

Through these regulations, CanCon continues to play a vital role in preserving Canadian cultural identity on television, fostering a distinct media ecosystem that supports Canadian creators and offers audiences meaningful access to domestic narratives amid an increasingly globalized and competitive media landscape.

21st Century Television and Streaming (2000s-Present)

The digital transformation of television represents a continuation of the technological evolution that began with radio’s adaptation to new platforms, yet the scope and speed of change in the streaming era have been unprecedented.

The 21st century has profoundly changed television consumption and production worldwide, and Canada is no exception. Several significant trends have reshaped the Canadian television landscape, including audience fragmentation, an explosion of content driven by digitization, increased competition among domestic broadcasters, and growing instability for traditional local broadcasting outlets.

One of the most significant shifts has been the rapid rise of cord-cutting: Canadians choosing to cancel or avoid traditional cable, satellite, or telco TV subscriptions in favour of internet-based streaming services. Between 2012 and 2019, approximately 2.5 million Canadian households either cut the cord or never subscribed to conventional TV providers in the first place (Taylor, 2017). This shift reflects a broader move toward on-demand, personalized viewing experiences that challenge traditional broadcast models and revenue streams.

As digital disruption reshaped how Canadians consumed media, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) responded with Let’s Talk TV: A Conversation with Canadians, a nationwide consultation launched in 2013. This initiative aimed to modernize Canada’s broadcasting regulations in response to changing technologies, viewer preferences, and economic pressures on traditional media.

By 2015, the CRTC introduced a series of reforms designed to increase choice, affordability, and transparency while continuing to support Canadian programming. Key outcomes included:

- Affordable, basic TV packages that let viewers choose only the channels they wanted, moving away from large, expensive bundles.

- Pick-and-pay channel options offer more customization and control over viewing.

- A new Television Service Provider Code of Conduct, promoting fairness and clear communication between providers and consumers.

- Rule changes now restrict replacing U.S. ads with Canadian ads during some shows, which has upset viewers.

- Improved access for Canadians with disabilities, supporting more inclusive media services.

- Reduced Canadian content (CanCon) quotas in some areas, reflecting the realities of a global media market.

- Updated funding models to sustain Canadian production despite shrinking ad revenues.

- A renewed focus on high-quality Canadian news services, recognizing their role in supporting informed citizenship.

These reforms signalled a shift from emphasizing the volume of Canadian content to promoting its quality and relevance.

At the same time, the rise of streaming platforms, often referred to as over-the-top (OTT) services, has radically reshaped the television landscape. Unlike traditional broadcasters, OTT services deliver content directly to viewers via the internet, bypassing cable and satellite providers entirely. Streaming giants such as Netflix, Amazon Prime Video, and newer entrants like Disney+, Apple TV+, and HBO Max have capitalized on the demand for premium, on-demand entertainment. Their rapid growth, especially between late 2019 and mid-2021, has redefined viewer expectations around choice, convenience, and personalization.

These platforms offer both significant opportunities and complex challenges for Canadian media. On one hand, they create new global pathways for Canadian creators, allowing them to reach audiences far beyond national borders. Shows like Anne with an E, Schitt’s Creek, and Kim’s Convenience have found international success through streaming platforms, demonstrating Canadian content’s global appeal. On the other hand, their international ownership and operations complicate the enforcement of Canadian content (CanCon) regulations. Many streaming services are not bound by the exact requirements that apply to domestic broadcasters, prompting urgent questions: How do we ensure that Canadian stories are discoverable in global digital libraries? What does it mean for Canadian cultural identity if algorithms, rather than national regulators, decide what audiences see?

The Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) and cultural policymakers are actively grappling with these questions. Recent developments include Bill C-11 (the Online Streaming Act), which aims to require digital platforms to contribute to Canadian content production funds and promote Canadian content discovery. These efforts reflect a broader concern about preserving cultural sovereignty and supporting a vibrant domestic creative sector in an era when a handful of global tech giants increasingly shape entertainment.

Indigenous broadcasting has also gained renewed attention in this digital transformation. Organizations like the Aboriginal Peoples Television Network (APTN) and various Indigenous-led podcast initiatives have leveraged digital platforms to preserve and promote Indigenous languages, stories, and perspectives. This represents both a continuation of earlier Indigenous media efforts and an evolution enabled by digital technologies’ lower barriers to entry.

Similarly, French-language broadcasting in Canada has adapted to the streaming era while maintaining its distinct cultural mandate. Radio-Canada’s digital platforms and French-language streaming services like Tou.tv have worked to serve francophone audiences while competing with global platforms that may offer limited French-language content.

As streaming continues to disrupt traditional broadcasting models, the stakes are clear: the choices we make today about regulation, content discoverability, and support for Canadian creators will help determine the future of Canada’s media landscape. Can the country maintain a distinct cultural voice amid the noise of global digital platforms? Or will Canadian content be drowned out by the sheer volume and marketing power of international competitors?

Summary

This chapter explores the evolution of broadcast media from radio’s experimental beginnings to today’s digital streaming era, examining how these technologies have transformed information delivery and entertainment consumption in Canada and globally.

Key Takeaways

Key takeaways from this chapter include:

- Radio’s development in Canada was shaped by both public and private interests, with the Canadian National Railway and later the CBC playing crucial roles in establishing national broadcasting that fostered Canadian identity

- Television’s emergence in the 1950s forced radio to adapt by focusing on music, portability, and immediacy, while Canadian content regulations were implemented to protect domestic cultural production amid American influences

- Podcasting emerged as a digital-native medium that combined radio’s intimate audio storytelling tradition with on-demand accessibility, democratizing content creation while raising questions about commercialization and algorithmic discovery

- The digital revolution brought streaming services that disrupted traditional broadcast models, challenging regulatory frameworks designed for conventional media while offering new opportunities for content creation and global distribution

- Throughout these transformations, Canadian broadcasting policy has consistently attempted to balance commercial interests with cultural sovereignty, creating a distinct approach to media regulation focused on preserving national identity while adapting to technological change

- The evolution from centralized broadcast schedules to personalized, on-demand consumption represents a fundamental shift in how audiences engage with media, yet core concerns about cultural representation and local content remain constant

As broadcasting continues to evolve in the digital age, the fundamental tensions between global influence and local expression, commercial success and cultural protection remain at the heart of Canadian media policy. The challenge for policymakers, creators, and audiences is to navigate these tensions while fostering innovation and preserving the diverse voices that define Canadian media culture.

Group Activity

Broadcast Media Debate

Group size: 4 teams (Radio, Television, Podcasts, Streaming)

Instructions:

- Form Teams: Divide into 4 groups, each representing one broadcast format: Radio, Television, Podcasts, or Streaming.

- Prepare Opening Statement: Each team briefly argues why their format is best for Canadian media. Consider: ○ Cultural significance ○ Technological advantages ○ Audience reach ○ Impact on Canadian content ○ Adaptability to change

- Present Opening Statements: Each team presents their argument to the class.

- Q&A Session: The moderator asks each team questions such as: ○ How does your format support Canadian creators? ○ How has your format adapted to digital disruption? ○ What challenges does your format face with Canadian content regulations?

- Class Vote and Discussion: Vote on: ○ Most persuasive team ○ Format most important for Canadian culture ○ Format best positioned for the future

Discuss how the different formats complement each other and what the future might hold for Canadian content policies.

End-of-Chapter Activity (News Scan)

Digital Disruption in Canadian Broadcasting

Purpose: This assignment helps you connect historical perspectives on broadcasting with contemporary developments, enhancing your ability to critically analyze how digital technologies transform traditional media systems and regulatory frameworks.

Using Google News, find a recent article (published in the last three months) about how streaming services or digital platforms impact traditional Canadian broadcasting.

In 250 words, respond to the following:

- Summarize the Article (100-150 words)

- Provide the title, author, and date in APA format.

- Explain the article’s primary focus and significance.

- Identify key findings or arguments presented.

- Connect to Chapter Themes (100-150 words)

- Relate the article to at least one key theme from this chapter (such as technological disruptions in broadcasting, regulatory challenges for Canadian content, broadcaster adaptation strategies, or the future of Canadian broadcasting).

- Analyze how the article illustrates continuity or change in broadcasting compared to historical patterns discussed in the chapter.

- Explain what the article suggests about the future trajectory of Canadian broadcasting.

Cite your sources (textbook and article) in APA format.

References

Aird Commission. (1929). Report of the Royal Commission on Radio Broadcasting. Government of Canada.

Abramson, A. (2003). The history of television, 1880 to 1941. McFarland & Company.

Armstrong, R. (2016). Broadcasting policy in Canada (2nd ed.). University of Toronto Press.

Babe, R. E. (2000). Canadian communication thought: Ten foundational writers. University of Toronto Press.

Berry, R. (2016). Podcasting: Considering the evolution of the medium and its association with the word “radio.” Radio Journal: International Studies in Broadcast & Audio Media, 14(1), 7–22. https://doi.org/10.1386/rjao.14.1.7_1

Boddy, W. (1990). Fifties television: The industry and its critics. University of Illinois Press.

Bottomley, A. J. (2015). Podcasting: A decade in the life of a “new” audio medium: Introduction. Journal of Radio & Audio Media, 22(2), 164–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/19376529.2015.1082880

Briggs, A., & Burke, P. (2005). A social history of the media: From Gutenberg to the Internet (2nd ed.). Polity Press.

Canada. (1991). Broadcasting Act (S.C. 1991, c. 11). https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/b-9.01/

Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission. (2015). The MAPL system – defining a Canadian song. https://crtc.gc.ca/eng/info_sht/r1.htm

Coe, L. (1996). Wireless radio: A brief history. MacFarland.

Douglas, S. J. (1987). Inventing American broadcasting, 1899–1922. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Eaman, R., Edwardson, R., & Gasher, M. (2024). Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. In The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/canadian-broadcasting-corporation

Faris, R. (1975). The passionate educators. Peter Martin Associates.

Fremeth, H. (2015). Television. In The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/television

Gasher, M., Skinner, D., & Lorimer, R. (2016). Mass communication in Canada (8th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Grant, J. (1907). Experiments and results in wireless telegraphy. The American Telephone Journal, 49–51. Reprinted at earlyradiohistory.us

Hendy, D. (2007). Life on air: A history of BBC radio broadcasting. Oxford University Press.

Hilmes, M. (2013). Radio voices: American broadcasting, 1922-1952. University of Minnesota Press.

Hong, S. (2001). Wireless: From Marconi’s black-box to the Audion. MIT Press.

Litt, P. (2012). The Massey Commission, Americanization, and Canadian cultural nationalism. Queen’s Quarterly, 119(2), 254–268.

Llinares, D., Fox, N., & Berry, R. (Eds.). (2018). Podcasting: New aural cultures and digital media. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90056-8

Lobato, R. (2019). Netflix nations: The geography of digital distribution. NYU Press.

Lorimer, R., & Gasher, M. (2004). Mass communication in Canada (5th ed.). Oxford University Press.

McChesney, R. W. (1992). Media and democracy: The emergence of commercial broadcasting in the United States, 1927–1935. OAH Magazine of History, 6(4), 23–28.

McLellan, J. (2011). Propaganda and mass persuasion: A historical encyclopedia, 1500 to the present. ABC-CLIO.

Miller, T., Govil, N., McMurria, J., Maxwell, R., & Wang, T. (2016). Global Hollywood (2nd ed.). British Film Institute.

Mosse, G. L. (2003). Nazi culture: Intellectual, cultural and social life in the Third Reich. University of Wisconsin Press.

Nahin, P. J. (2001). The science of radio: With MATLAB and electronics experiments. Springer.

Raboy, M. (1990). Missed opportunities: The story of Canada’s broadcasting policy. McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Scannell, P., & Cardiff, D. (1991). A social history of British broadcasting: Volume One 1922-1939, serving the nation. Blackwell.

Spigel, L. (1992). Make room for TV: Television and the family ideal in postwar America. University of Chicago Press.

Sterling, C., & Kittross, J. M. (2002). Stay tuned: A history of American broadcasting (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Taras, D. (2015). Digital mosaic: Media, power and identity in Canada. University of Toronto Press.

Taylor, G. (2017). Shut off: The Canadian digital television transition. McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Vipond, M. (1992). Listening in: The first decade of Canadian broadcasting, 1922–1932. McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Vipond, M. (2000). The mass media in Canada (3rd ed.). James Lorimer & Company.

Wagman, I., & Urquhart, P. (Eds.). (2012). Cultural industries.ca: Making sense of Canadian media in the digital age. James Lorimer & Company.

Media Attributions

- Marconi

- 1906-07

- John Aird in Los Angeles

- Early Television – Tiverton Museum