5 Chapter 5: Photography, Illustration, and the Rise of Visual Culture

Amanda Williams

Introduction

We live in an age saturated with images. From the cameras embedded in our smartphones to the constant stream of visual content on social media, photography has become a central way of seeing, recording, and communicating. Despite its everyday presence, photography is a relatively recent invention compared to the much older print medium. Yet the desire to capture and communicate through images stretches back thousands of years. Long before the printing press, human beings relied on visual expression through cave paintings, carved symbols, illuminated manuscripts, and detailed illustrations. In medieval Europe, “picture writers” served a vital function by visually conveying stories and teachings to audiences who often could not read (Hughes, 2017).

This chapter places the evolution of photography and illustration within a broader cultural shift sometimes described as the visual turn. As technologies for creating and sharing images developed, so did our understanding of what images can do. Photography introduced new possibilities for realism, documentation, and mass communication. At the same time, illustration remained a powerful tool for explaining ideas, guiding thought, and shaping opinion. These visual forms have played essential roles in education, journalism, advertising, and design.

The relationship between visual technology and culture has deeply influenced how societies remember their histories, represent identities, and respond to change in Canada and worldwide. This chapter explores how photography and illustration have served as both creative practices and tools of communication. It also examines how certain photographs become iconic, anchoring our memory of key historical and social events.

By studying these media, we can better understand how the visual revolution continues to shape culture today. The ability to interpret and create images has become as important as reading and writing, a crucial skill in our image-driven world.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Identify how illustration provides the foundation for photography by recognizing key artistic and technological developments.

- Describe photography from its earliest forms to contemporary practices, including ethical dilemmas related to digital manipulation and consent.

- Examine the development of photography in Canada, exploring its technological advancements, key figures, and the contributions of women photographers while investigating how the medium has shaped and reflected Canadian national identity from its early adoption to contemporary practices.

- Analyze photography’s historical and contemporary status as an art form by evaluating its role in cultural expression and public discourse.

The Illustrative Foundation of Photography

Illustration provides the essential foundation upon which photography would later build. Before the rise of printed books, illustrators known as “picture writers” were active from late antiquity through the medieval period, roughly between the 3rd and 15th centuries. These artists created detailed visual narratives communicating ideas and stories in societies where literacy was limited to elites. Their early images employed techniques such as symbolism, composition, and sequential storytelling that shaped how visual communication developed. Their work helped establish key principles of visual storytelling—like framing, perspective, and the use of light and shadow—that would later influence photographic composition and narrative (Hughes, 2017).

As illustration moved from unique, handcrafted manuscripts to mechanically reproducible prints, new economic and artistic dynamics emerged. The ability to reuse woodcut blocks in multiple publications drastically lowered production costs and allowed publishers to reach broader audiences. This shift introduced commercial pressures that influenced the style and function of illustrations. The value of an image became linked not only to its artistic quality but also to its reproducibility and market appeal. Publishers increasingly used attractive and attention-grabbing images as marketing tools, integrating advertising into books and periodicals. These economic imperatives created precedents for the photographic industry, where cost-effective image production and audience engagement remain crucial, particularly in advertising, journalism, and commercial photography (Bland, 1969).

This period set the stage for photography by demonstrating how mechanical reproduction could expand access to images while shaping their meaning through market demands. The balance between artistic expression, technical reproduction, and commercial viability established during this era continues to inform photographic practice today.

Before the invention of photography, the printing press revolutionized visual communication by making illustrations more accessible and reusable, lowering production costs and allowing images to reach a much wider audience.

The Cultural Shift Toward Visual Realism

By the mid-19th century, significant social and economic changes were reshaping Western societies, creating fertile ground for new visual technologies and modes of representation. Literary historian Altick (1957) identified three key prerequisites for the emergence of a mass reading public: widespread literacy, increased leisure time, and disposable income. The growth of this audience created new cultural expectations around visual media. People increasingly desired images that reflected the world as it appeared to the naked eye, showing detailed, accurate depictions rather than stylized or symbolic renderings. This demand for naturalism and realism in illustration was part of a broader cultural shift toward empirical observation and scientific inquiry, which valued truthful representation over artistic interpretation (Marien, 2015).

This cultural movement set the stage for photography’s rapid adoption by fostering an environment receptive to mechanical reproduction of images that promised a more objective and precise visual record. Several key technological devices helped bridge the gap between traditional hand-drawn illustration and photographic representation by changing how artists and viewers saw the world.

The Claude Glass, popular in the 18th and early 19th centuries, was a small, slightly convex mirror that reflected a scene with reduced detail and tonal contrast. Artists and travellers used it to frame and compose landscape views resembling paintings. This device trained people to see landscapes as composed images, emphasizing framing and selective representation rather than a continuous, naturalistic field of vision. This reframing of visual experience was an important conceptual step toward understanding photography as an art of selection and composition (Crary, 1990).

The Camera Lucida, patented in 1807, further advanced this idea by allowing artists to superimpose the image of a subject directly onto their drawing surface using a prism. This optical aid enabled artists to trace outlines and capture proportions with greater accuracy and speed than freehand drawing allowed. Though requiring some skill to use effectively, the Camera Lucida represented a critical technological development in the quest for more precise and realistic visual depiction, anticipating photography’s goal of faithful representation (Gernsheim & Gernsheim, 1969).

The Camera Obscura, refined over the 17th and 18th centuries, was a darkened room or box with a small aperture that projected an inverted image of the outside scene onto a surface inside. This projection allowed users to study natural light, perspective, and detail as a basis for drawing or painting. By transforming the act of seeing into an experience of mediated image projection, the Camera Obscura fundamentally changed how artists and observers conceptualized vision. It trained users to perceive the world as an image to be captured and framed, rather than merely experienced directly, aligning closely with the principles of photographic vision that would soon follow (Crary, 1990; Gernsheim & Gernsheim, 1969).

Together, these devices cultivated a cultural and conceptual foundation for photography. They fostered new ways of seeing that emphasized mechanical objectivity, framing, and the faithful recording of visual reality. This shift not only prepared artists and audiences for the arrival of photography but also helped establish the expectations that photography should be a medium capable of capturing and preserving the truth of the visual world.

The Birth and Evolution of Photography

The Pioneers of Photography

Several individuals working independently discovered photography’s basic principles almost simultaneously in the early 19th century. This period of rapid innovation reflected broader scientific advancements, industrial developments, and growing societal interests in mechanical image reproduction and visual documentation. These factors, combined with artistic ambitions to create new ways of capturing and preserving reality through technology. Three key pioneers—Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, Louis Daguerre, and William Fox Talbot—established the fundamental approaches that defined photography’s early development and laid the groundwork for the diverse photographic practices that followed.

Joseph Nicéphore Niépce (1765–1833) is widely credited with creating the world’s first successful permanent photograph in 1827, a heliograph titled View from the Window at Le Gras. This pioneering image required approximately eight hours of exposure and was produced using a bitumen-coated pewter plate. When exposed to light, the bitumen hardened, allowing Niépce to wash away the unhardened portions and create a fixed image. Although Niépce’s process was groundbreaking as the first to restore an image permanently, it was impractical for widespread use due to extremely long exposure times and the challenge of reproducing the images reliably (Frizot, 1998).

Louis Daguerre (1787–1851), who initially collaborated with Niépce, significantly advanced photographic technology by developing the daguerreotype process. Publicly announced in 1839, this method dramatically reduced exposure times to mere minutes and produced highly detailed, sharp images on silver-plated copper sheets. The daguerreotype rapidly gained popularity in France, the United States, and beyond, prized for its ability to capture fine details and its relatively quick processing time. Despite its clarity and detail, the daguerreotype produced a single, unique image that could not be duplicated, which limited its commercial versatility (Marien, 2015).

William Fox Talbot (1800–1877) independently developed the calotype process, introducing a revolutionary negative-positive photographic method. Unlike the daguerreotype, calotypes used paper coated with silver iodide to create a negative image, from which multiple positive prints could be made. While calotypes were less sharp and detailed than daguerreotypes, Talbot’s process was a significant step toward reproducible photography and laid the technical foundation for modern photographic printing and mass distribution. Talbot also emphasized photography’s potential as both an artistic and documentary medium, influencing how photography was perceived and used culturally (Newhall, 1982).

These parallel and nearly simultaneous advancements by Niépce, Daguerre, and Talbot illustrate how photography emerged from scientific curiosity, industrial innovation, and artistic experimentation. Their discoveries across different countries and contexts suggest that the invention of photography was not simply the product of isolated genius but rather an inevitable outcome of broader technological and cultural forces shaping the early to mid-19th century (Frizot, 1998; Marien, 2015; Newhall, 1982).

The Democratization of Photography

The democratization of photography was a crucial turning point in its history, shifting the medium from an elite, expensive practice to an accessible and widespread cultural phenomenon. While the foundational work of Niépce, Daguerre, and Talbot established photography as a viable imaging technology, its true expansion occurred when advancements made it affordable and user-friendly for the general public.

George Eastman (1854–1932), founder of Kodak, played a pivotal role in this transformation. In 1888, Eastman introduced the Kodak camera, a handheld device preloaded with flexible roll film, which eliminated the need for glass plates and complex chemical processing. This innovation allowed users to take multiple photographs before sending the entire camera to Kodak for film development and printing, making photography significantly more accessible (Hannavy, 2007). The process was further refined with the release of the Kodak Brownie in 1900, priced at just one dollar, with film costing 15 cents per roll. Eastman’s famous marketing slogan, “You press the button, we do the rest,” encapsulated the shift toward accessibility by removing technical barriers that had previously restricted photography to professionals, scientists, and wealthy enthusiasts (West, 2000).

This democratization process rapidly expanded photography’s cultural and social significance. By the early 20th century, photography had become an everyday household activity, enabling individuals to document personal experiences, family life, and historical events. The accessibility of portable cameras allowed amateur photography to rise, significantly influencing visual culture and media. Newspapers and magazines increasingly relied on photographic images, and the ability to record everyday life fundamentally altered how people engaged with memory, identity, and historical documentation (Marien, 2015).

From 1826 to 1900, the period saw more than 30 significant advancements in photographic processes, with innovations ranging from chemical refinements to mechanical improvements. The development of dry plates in the 1870s allowed for faster shutter speeds and more convenient processing, making cameras more straightforward to use outside controlled studio settings (Newhall, 1982). In addition, advancements in printing techniques, such as the halftone process, enabled the mass reproduction of photographs in books and newspapers, further integrating photography into everyday life (Batchen, 2002). This rapid technical evolution reflected photography’s extraordinary cultural momentum, transforming it from a scientific curiosity into an essential documentary and artistic tool.

The democratization of photography ultimately reshaped how societies recorded history, preserved memories, and communicated visually. By removing economic and technical barriers, figures like Eastman ensured that photography became integral to modern life, paving the way for its continued evolution through film, instant photography, and digital imaging.

Photography as Art: The Ongoing Debate

The emergence of photography in the 19th century ignited intense debates about whether it should be considered a legitimate form of artistic expression. These discussions were not merely theoretical but carried significant cultural, economic, and legal implications, reflecting broader tensions about creativity, technical skill, and the nature of artistic production.

One of the most vocal critics of photography as art was the French poet and art critic Charles Baudelaire, who dismissed it as the “refuge of failed painters with too little talent” (Marien, 2015, p. 75). Baudelaire’s critique reflected the belief that true art required the touch of an artist’s hand and that photography, as a mechanical process, lacked the depth of human creativity. However, other voices championed the artistic potential of photography precisely because of its mechanical nature, arguing that it offered new ways of seeing and representing the world. As early as the 1850s, photographers such as Gustave Le Gray and Julia Margaret Cameron experimented with composition, lighting, and focus, elevating photography beyond mere documentation to artistic expression (Rosenblum, 2007).

The economic impact of photography’s rise further complicated its artistic status. The camera directly threatened traditional portrait painters, whose livelihood depended on commissioned works. With the affordability and accessibility of photographic portraits, the demand for painted portraits declined dramatically, leading many artists to frame photography as a mechanical product rather than a creative medium. This economic anxiety contributed to the resistance against recognizing photography as an art form, as many feared it would devalue traditional artistic skills (Batchen, 1999).

Legal debates in the late 19th century also played a crucial role in shaping photography’s status. Early copyright disputes questioned whether photographs should be considered original creative works or simple reproductions of reality. Photographers sought legal recognition for their work, arguing that composition, lighting, and subject choice reflected artistic intention. These debates influenced broader discussions about intellectual property, setting important precedents for how photography was perceived within artistic and legal frameworks (Tagg, 1988).

The debates surrounding photography’s artistic legitimacy were not confined to the 19th century but continue to resonate in the digital age. The advent of digital photography, AI-generated imagery, and social media has revived fundamental questions about the role of technology in artistic creation. While photography is now firmly established as an art form, the ongoing discourse about authorship, originality, and mechanical reproduction echoes the tensions that first emerged in the 19th century. Photography’s evolution from a contested medium to an accepted art form highlights the dynamic relationship between human creativity and technological innovation, a debate that remains relevant in contemporary visual culture.

Photography in Canada: A Rich National Tradition

Photography in Canada has a distinctive history that reflects international trends and uniquely Canadian concerns. The evolution of Canadian photography demonstrates how the medium adapted to local contexts while participating in global technological and artistic developments.

Early Canadian Photography

Canadian engagement with photography began shortly after the medium’s invention, with the Quebec Gazette, Toronto Patriot, and Halifax Colonial Pearl reporting on daguerreotypes and calotypes in 1839 (Tweedie & Cousineau, 2022). By the early 1840s, American daguerreotypists Halsey and Sadd had established studios in Montréal and Québec. At the same time, Mrs. Fletcher (no first name given) became one of the first female photographers in the country (Tweedie & Cousineau, 2022). Thomas Coffin Doane, known for his portraits of Lord Elgin and Louis-Joseph Papineau, was a leading daguerreotypist in Montréal and received recognition at the Paris Exhibition of 1855. This early Canadian engagement with photography demonstrated the medium’s rapid global spread and adaptation to local contexts and needs (Greenhill & Birrell, 1979).

The mid-to-late 19th century saw the rise of the wet collodion process, which allowed for more explicit images and mass production of photographs. William Notman, one of Canada’s most influential photographers, established a vast studio network across the country and the United States. His 1858 documentation of the Victoria Bridge’s construction and appointment as the Queen’s photographer in 1860 cemented his reputation. By the 1870s, Notman and his team produced over 14,000 negatives annually, pioneering composite photography techniques, such as his famous 1869 Skating Carnival montage (Tweedie & Cousineau, 2022). At the same time, landscape photographers like Alexander Henderson captured the Canadian environment in albums such as Canadian Views and Studies. These efforts established a distinctively Canadian photographic tradition that balanced artistic aspirations with commercial viability (Schwartz, 2018; Triggs, 1994).

Technological advancements in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including the introduction of dry plates and portable cameras, expanded photography’s reach throughout Canadian society. Government-backed photography efforts gained momentum, particularly with the Canadian War Records Office during World War I. William Ivor Castle and William Rider-Rider documented major battles involving Canadian forces, though some images were later revealed to be staged (Tweedie & Cousineau, 2022).

The mid-20th century saw the rise of photojournalism, with publications like Weekend and Toronto Star Weekly commissioning photographers such as Ottawa’s Yousuf Karsh, whose dramatic portraiture made him internationally famous. These developments reflected photography’s growing institutional importance in Canadian national identity and historical documentation (Payne & Kunard, 2011).

Women’s Contributions to Canadian Photography

Women’s contributions to Canadian photography have often been overlooked, creating a one-sided vision of the country’s photographic history. Recovering and recognizing these contributions provides a more complete understanding of photographic practice and Canadian social history. Below are highlighted some key contributors.

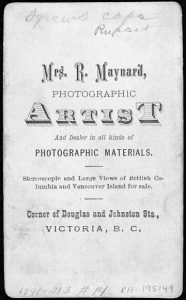

Hannah Maynard (1834–1918) established herself as a creative and technical innovator in 19th-century Victoria, British Columbia. She opened a studio under the name “Mrs. R. Maynard, a Photographic Artist and Dealer in All Kinds of Photographic Materials,” and by 1897 had become Victoria’s official police photographer. Beyond her commercial work, she experimented with photomontages, multiple exposures, and photosculptures. Her Gems of British Columbia series (1881–1895), an annual composite photograph featuring children’s portraits, was repurposed as New Year’s greeting cards. Her use of mirrors and glass negatives to create surreal self-portraits and memorial images was groundbreaking, positioning her among the most technically advanced photographers of her time. Maynard’s work demonstrates how women photographers often combined commercial practice with experimental techniques, challenging the conventional division between practical and artistic photography (Eamon, 2018; Jones, 2017; Mattison, 1985).

Through striking glass plate photography, Mattie Gunterman (1872–1945) documented life in British Columbia’s remote frontier regions. Originally from Wisconsin, she moved north with her husband for a healthier climate. She took up photography using a 4×5-inch glass plate camera, which allowed for sharper images and more controlled exposures. Her photographs depict pioneer life, including mining camps, railroad workers, and deceased miners being transported for burial. Using an extended cable release, Gunterman incorporated herself into her photographs, creating early examples of self-portraiture in frontier settings. In 1969, 200 of her negatives were rediscovered in an abandoned storage shed in Beaton, British Columbia, bringing renewed attention to her work. This rediscovery exemplifies how women’s photographic contributions often required archaeological recovery to enter the historical record, having been marginalized in their own time (Jones, 2017; Morin, 2018; Near, 1988).

Geraldine Moodie (1854–1945) is recognized for her documentary work on Indigenous communities and Canada’s northern frontier. Beginning as a photographer of botanical illustrations for her great-aunt Catherine Parr Traill, she later established studios in Battleford and Maple Creek, Saskatchewan, and Medicine Hat, Alberta. Her 1895 images of the Cree Sun Dance and Prime Minister Mackenzie Bowell’s commission to document Riel Rebellion sites highlight her role in visual historical documentation. While accompanying her husband on a North West Mounted Police expedition to the Arctic in 1904, Moodie continued photographing the region despite being denied official photographer status. Today, over 600 of her photographs are preserved at the Glenbow Museum in Calgary. Her work represents a critical intersection of colonial photography and ethnographic documentation, providing valuable historical records while also reflecting the complex power dynamics of her era (Eber, 1994; Jones, 2017; White, 1998).

Gladys Reeves (1890–1974) played a vital role in documenting Alberta’s pioneer history and urban development. After starting as a receptionist at Ernest Brown’s photography studio in Edmonton, she established her own business with Brown’s support. Despite setbacks, including a devastating fire that destroyed 5,000 prints, Reeves persevered. In the 1930s, Reeves helped create The Birth of the West photo series for Alberta’s public schools, preserving early settler history. Beyond photography, she was active in Edmonton’s beautification projects, advocating for green spaces and horticultural initiatives. Reeves exemplifies how women photographers often combined commercial practice with civic engagement and education, using their visual skills in service of community development (Jones, 2017; Millar, 2007; Payne & Kunard, 2011).

Elsie Holloway (1890–1971) was a leading portrait photographer in Newfoundland, operating Holloway Studio for 40 years. She and her brother Bert inherited their father’s passion for photography and opened a studio in 1908. After Bert’s death in World War I, Holloway ran the business independently, producing highly sought-after portraits. Her career highlights include photographing Amelia Earhart in 1932 and covering the royal tour of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth in 1939. Although authorship of some images remains uncertain due to the “Holloway” stamp used by multiple family members, many of her surviving glass negatives are housed in the Provincial Archives of Newfoundland and Labrador. Holloway’s career demonstrates how women sustained photographic businesses through challenging circumstances, maintaining commercial viability and artistic standards (Gosling, 1996; Jones, 2017; Payne, 2013).

These photographers represent just a few women who have shaped Canadian photography. Their contributions highlight women’s diverse roles in documenting history, pushing artistic boundaries, and sustaining photographic businesses. While their work has often been overlooked, continued research and recognition help to restore their place in Canada’s photographic heritage.

Institutional Development and Contemporary Canadian Photography

By the late 20th century, photography in Canada had firmly established itself as a documentation tool and a respected and evolving art form. A key moment in this institutional development was the launch of the Still Photography Division of the National Film Board (NFB) in 1941. This division aimed to document Canadian life during and after World War II visually. Under the leadership of figures like John Grierson and Donald Buchanan, the NFB hired photographers such as Karsh, Duncan Cameron, and Rosemary Gilliat to build a visual archive of the nation (Tweedie & Cousineau, 2022). These early efforts began a sustained public investment in photographic storytelling and nation-building.

In 1985, the founding of the Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography (CMCP) formalized the country’s commitment to preserving and promoting photography as an essential cultural medium. Although the CMCP was later absorbed into the National Gallery of Canada in 2011, it helped legitimize photography within national art discourse. It showcased the work of emerging and established Canadian photographers (Payne, 2013). This institutional momentum provided a platform for artists like Jeff Wall, known for his cinematic lightbox tableaux exploring urban life and social constructs; Shelly Niro, whose work focuses on Indigenous identity and feminist storytelling; and Raymonde April, whose photographs often blur the boundaries between documentary and poetic reflection.

Contemporary Canadian photography thrives within a vibrant ecosystem of artist-run centres, public galleries, and university programs that support experimental and socially engaged work. Festivals such as the Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival in Toronto, the largest photography event in the world, highlight Canada’s engagement with global conversations while foregrounding local issues such as reconciliation, migration, urbanization, and ecological change (Scotiabank CONTACT, 2024).

Government funding through the Canada Council for the Arts and provincial arts councils has also sustained photography’s growth as both an art form and a tool of cultural critique. These frameworks support photographers who address topics such as climate justice, identity politics, and digital surveillance, contributing to a distinctive Canadian photographic tradition. While strongly connected to international visual culture developments, Canadian photography is committed to specific national histories, geographies, and social concerns (Langford, 1996; Enright, 2013).

Contemporary Issues in Photography

Photography is undergoing a rapid transformation in today’s digital landscape, driven by artificial intelligence (AI), computational editing, and platform-based distribution. These shifts raise important questions about truth, authorship, representation, and ethics. The lines between photography as documentation and creative expression have become increasingly blurred. These issues are central to our study of visual culture and closely connect to the ethical dilemmas referenced in our learning outcomes.

Digital Manipulation and Ethical Boundaries

The move from analog to digital technologies has dramatically changed how photography functions as a tool for representation. Digital editing software such as Photoshop, Lightroom, and newer AI tools like Midjourney, Runway ML, and DALL·E make image manipulation easier and more accessible than ever before. This accessibility raises complex ethical questions about the authenticity of photographs and their role in different social and professional contexts.

In fields like photojournalism, ethical guidelines emphasize factual accuracy. Most news organizations allow only minimal adjustments to exposure or cropping and prohibit alterations that could mislead viewers. For example, The New York Times has strict editorial standards prohibiting digital manipulations that distort the meaning of images (Lister, 2013; Wells, 2015). In contrast, extensive manipulation is typical and often expected in commercial and artistic fields. Fashion photography frequently involves significant retouching, and contemporary artists like Jeff Wall use staged, digitally composited images to tell complex visual stories.

New ethical dilemmas have emerged with the rise of AI-generated imagery. In 2023, an AI-generated image of Pope Francis in a white puffer jacket went viral on Reddit and Twitter. Many viewers believed the image was real, illustrating how generative AI can create highly convincing fakes that spread quickly on social media (Hern, 2023). In another example, German artist Boris Eldagsen declined a photography award from the Sony World Photography Awards after revealing that his winning image was generated using AI. He used the opportunity to provoke a conversation about what photography means in an era when machines can simulate it (Vincent, 2023).

The boundaries of authorship and ownership are also being challenged. Tools like Stable Diffusion and Midjourney are trained on millions of online images, often without consent or credit to the original creators. This raises unresolved questions about the ethics of training data, intellectual property, and creative labour (Crawford, 2021). The work of appropriation artists such as Richard Prince, who reuses Instagram images with minimal changes, continues to test legal and moral definitions of originality (Lessig, 2008; Manovich, 2001).

Facial recognition and biometric technologies further complicate matters by using photographic data to identify and track individuals, often without their knowledge or permission. These tools are increasingly embedded in public surveillance systems and social media applications, raising concerns about consent, racial profiling, and political control (Crawford, 2021).

In addition, social media algorithms play a powerful but invisible role in shaping photographic practices. Platforms like Instagram and TikTok reward specific images over others, influencing what users post and how they frame or edit their content. These algorithmic pressures shape cultural tastes, visibility, and self-perception (Cotter, 2019; Bucher, 2020).

In this evolving context, photographers’ ethical responsibilities extend beyond technical accuracy. They must also consider questions of manipulation, audience perception, consent, authorship, and algorithmic influence.

The Value of Photography in an Age of Abundance

One of photography’s most significant cultural shifts is the sheer abundance of images. With smartphones, social media, and AI tools, billions of photographs are taken, shared, and discarded daily. This image saturation has led some critics to argue that photographs have lost their cultural weight or “sacredness” because they are so easily created and consumed.

Susan Sontag (1977) warned that photography’s power to preserve a moment could be diluted if the medium became too ubiquitous. In the twenty-first century, that concern has become reality. Studies estimate that over three billion images are shared online daily, often scrolling past viewers in seconds before being forgotten. Many of these photos are not carefully composed or edited but are produced quickly for temporary visibility on platforms like Snapchat or Instagram Stories.

Yet despite this abundance, certain photographs continue to achieve lasting cultural impact. Images of political protests, climate disasters, or acts of resistance still resonate globally. These photographs gain their significance not just from their visual content, but also from their timing, distribution, and the public conversations they spark.

AI-generated imagery introduces new challenges to this ecosystem. Platforms like OpenAI’s DALL·E or Adobe Firefly can produce photorealistic scenes that appear indistinguishable from human-taken photographs. This raises a new question: Will iconic images of the future be made by cameras or algorithms? And will viewers still respond with the same emotional or historical investment?

As Rubinstein and Sluis (2008) point out, digital photography functions more as a “social practice” than a material object. Today’s photographs are often used to signal identity, affiliation, or mood rather than to document events. The value of photography now lies not only in what is shown, but in how images are circulated, tagged, filtered, and shared.

Nevertheless, photography retains its importance as a form of evidence, memory, and artistic expression. Photography continues to inform public understanding and shape global narratives in journalism, scientific documentation, and human rights advocacy contexts. Projects like AI-assisted photo restoration of archival images also demonstrate how new technologies can expand, rather than diminish, photography’s cultural value.

In an era of visual overproduction, the challenge is to create compelling images while preserving their meaning and ethical integrity. Developing critical visual literacy, which involves understanding how images are made, manipulated, and received, is more critical than ever.

Summary

The evolution of photography from its illustrative foundations to today’s digital realm represents one of the most significant media transformations in history.

Key Takeaways

Key takeaways from this chapter include:

- Photography bridges art and technology, with innovation enabling new artistic possibilities while challenging traditional concepts of creativity and authorship. This relationship continues to evolve from daguerreotypes to digital manipulation.

- Photography’s shift from an elite practice to an everyday activity has expanded access, bringing new perspectives and creating hierarchies based on distribution, expertise, and cultural capital.

- Canadian photography reflects global trends and local concerns, shaped by key figures and women photographers, and has played a vital role in documenting and defining Canadian national identity.

- As photography becomes more manipulable, especially with AI, ethical questions around authenticity, representation, consent, and power shape how images are created, shared, and interpreted in the digital age.

Understanding photography’s rich history provides essential context for navigating today’s image-saturated environment. Whether as consumers or creators of visual content, recognizing photography’s technical, artistic, and ethical dimensions enables us to engage more critically and thoughtfully with the images that increasingly shape our understanding of the world. As photography evolves technologically, its fundamental tensions, mechanical reproduction and artistic expression, objective documentation and subjective interpretation, mass accessibility and cultural value remain as relevant as ever to our visual literacy and cultural understanding.

Group Activity

Framing the Debate: Is Photography Art or Technology?

This activity encourages critical engagement with the evolution of photography by debating whether it is primarily an artistic medium or a technological innovation. Students will develop structured arguments, discuss, and reflect on photography’s dual role in society.

Team Roles & Preparation

Divide into five groups:

Teams A & B: Photography as Art

- Defend photography as a creative discipline.

- Emphasize composition, lighting, emotion, and artistic intent.

Prepare 4-5 key points using historical and contemporary examples (e.g., fine art photography, documentary photography).

Teams C & D: Photography as Technology

- Argue that technological advancements drive photography.

- Highlight innovations like the daguerreotype, film, digital sensors, and AI-generated imagery.

Prepare 4-5 key points using examples of how technology has shaped photography’s accessibility and function.

Group E: Neutral Observers

Analyze both perspectives, ask clarifying questions, and summarize key insights.

Debate & Discussion

- Each side presents its opening arguments (2 minutes per team).

- Observers pose questions to challenge each perspective.

- Teams provide counterarguments (2 minutes per team).

The class votes on which side made the stronger case.

Reflection & Takeaways

- How have artistic and technological elements shaped photography historically?

- Can photography exist without technology? Can it exist without artistic vision?

- How does modern digital photography blur the lines between art and technology?

At the end of the discussion, Group E will summarize the key arguments and broader implications for understanding photography’s role in visual culture.

End-of-Chapter Activity (News Scan)

Photography in the Digital Age

Purpose: This assignment helps you connect historical perspectives on photography with contemporary developments, enhancing your ability to analyze visual media through historical and current lenses critically.

Using Google News, find a recent article (published in the last three months) about the current state, challenges, or innovations in photography in Canada or globally.

In 250 words, respond to the following:

- Summarize the Article (100-150 words)

- Provide the title, author, and date in APA format.

- Explain the article’s primary focus and significance.

- Identify key findings or arguments presented.

- Connect to Chapter Themes (100-150 words)

- Relate the article to at least one key theme from this chapter (such as technological advancements, ethical concerns, artistic movements, or photography’s role in society).

- Analyze how the article illustrates continuity or change in photography compared to historical patterns discussed in the chapter.

- Explain what the article suggests about the future trajectory of photography.

Cite your sources (textbook and article) in APA format.

Note: This assignment will help you connect historical perspectives on photography with contemporary developments, enhancing your ability to analyze visual media critically through historical and current lenses.

References

Altick, R. D. (1957). The English common reader: A social history of the mass reading public, 1800-1900. University of Chicago Press.

Batchen, G. (1999). Burning with desire: The conception of photography. MIT Press.

Batchen, G. (2002). Each wild idea: Writing, photography, history. MIT Press.

Bland, D. (1969). A history of book illustration: The illuminated manuscript and the printed book (2nd ed.). University of California Press.

Bucher, T. (2020). The algorithmic imaginary: Exploring the ordinary affects of Facebook algorithms. Information, Communication & Society, 23(1), 76–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2018.1476147

Cotter, K. (2019). Playing the visibility game: How digital influencers and algorithms negotiate influence on Instagram. New Media & Society, 21(4), 895–913. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444818815684

Crawford, K. (2021). Atlas of AI: Power, politics, and the planetary costs of artificial intelligence. Yale University Press.

Crary, J. (1990). Techniques of the observer: On vision and modernity in the nineteenth century. MIT Press.

Eamon, M. (2018). Image and inscription: An anthology of contemporary Canadian photography. Gallery 44 & YYZ Books.

Eber, D. (1994). Geraldine Moodie: An inventory of photographs. Canadian Photography Institute.

Frizot, M. (Ed.). (1998). A new history of photography. Könemann.

Gernsheim, H., & Gernsheim, A. (1969). The history of photography from the camera obscura to the beginning of the modern era. McGraw-Hill.

Gosling, A. (1996). Moments in time: Photographs from the Holloway Studio. Provincial Archives of Newfoundland and Labrador.

Greenhill, R., & Birrell, A. (1979). Canadian photography: 1839-1920. Coach House Press.

Hand, M. (2012). Ubiquitous photography. Polity Press.

Hannavy, J. (2007). Encyclopedia of nineteenth-century photography. Routledge.

Hern, A. (2023, March 27). Photo of Pope in puffer jacket was AI-generated, fooling millions online. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2023/mar/27/photo-of-pope-in-puffer-jacket-was-ai-generated

Hughes, B. (2017). A lost world: The missed history of illustration. The International Journal of the Image, 8(2), 69–75. https://doi.org/10.18848/2154-8560/CGP/v08i02/69-75

Hughes, L. (2017). Visual storytelling: The art and technique. Routledge.

Jones, J. (2017). Pioneer photographers of Canada. University of Toronto Press.

Langford, M. (1996). Canadian women photographers: A survey. Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography.

Lessig, L. (2008). Remix: Making art and commerce thrive in the hybrid economy. Penguin Press.

Lister, M. (Ed.). (2013). The photographic image in digital culture (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Manovich, L. (2001). The language of new media. MIT Press.

Marien, M. W. (2015). Photography: A cultural history (4th ed.). Routledge.

Mattison, D. (1985). The multiple self of Hannah Maynard. National Archives of Canada.

Millar, N. (2007). Gladys Reeves: A life’s worth. Provincial Archives of Alberta.

Morin, P. (2018). Mattie Gunterman: Her art and life. Mitchell Press.

Near, H. (1988). Mattie Gunterman: A pioneer photographer at Thomson’s Landing. B.C. Historical News.

Newhall, B. (1982). The history of photography: From 1839 to the present. Museum of Modern Art.

Payne, C. (2013). The official picture: The National Film Board of Canada’s still photography division and the image of Canada, 1941-1971. McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Payne, C., & Kunard, A. (Eds.). (2011). The cultural work of photography in Canada. McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Ritchin, F. (2013). Bending the frame: Photojournalism, documentary, and the citizen. Aperture.

Rosenblum, N. (2007). A world history of photography (4th ed.). Abbeville Press.

Rosler, M. (2004). Decoys and disruptions: Selected writings, 1975-2001. MIT Press.

Rubinstein, D., & Sluis, K. (2008). A life more photographic: Mapping the networked image. Photographies, 1(1), 9–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/17540760701785842

Schwartz, J. M. (2018). Picturing place: Photography and the geographical imagination. I.B. Tauris.

Sontag, S. (1977). On photography. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Tagg, J. (1988). The burden of representation: Essays on photographies and histories. University of Minnesota Press.

Triggs, S. (1994). William Notman: The stamp of a studio. Art Gallery of Ontario.

Tweedie, K., & Cousineau, P. (2022). Photography in Canada. The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/photography

Vincent, J. (2023, April 17). AI-generated image wins prestigious photography prize—but creator refuses award. The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2023/4/17/23686699/sony-world-photography-awards-ai-generated-image

Wells, L. (2015). Photography: A critical introduction (5th ed.). Routledge.

West, N. M. (2000). Kodak and the lens of nostalgia. University of Virginia Press.

White, D. (1998). In search of Geraldine Moodie: A pioneer female photographer of the Canadian North. Polar Record, 34(188), 37-44.

Media Attributions

- Kodak

- Verso_of_carte-de-visite_showing_studio_logo_of_Hannah_Maynard,_ca._1868-1878

- Susan_Sontag_1979_©Lynn_Gilbert