4 Chapter 4: The Evolution of Newspapers

Amanda Williams

Introduction

The printing press revolutionized news distribution, laying the foundation for modern newspapers. North America’s first newspaper, Publick Occurrences, Both Foreign and Domestick, was published in 1690 but quickly banned due to content objections and the lack of guaranteed free speech (Clarke, 1994). This early suppression highlights the ongoing tension between publishers, readers, and authorities.

Newspapers emerged as a key product of the broader print revolution that began with Gutenberg’s movable-type press in the mid-15th century. This breakthrough drastically lowered the cost of producing written materials and expanded access to information beyond the elite. As printed books spread literacy and ideas across Europe, the press also enabled more timely and accessible formats such as pamphlets, newsletters, and newspapers that responded to current events. Newspapers became vital for public discourse, political critique, and community awareness, reinforcing print’s power to shape social and political life. This legacy continued into the colonial era, with print technology crucial to establishing a press infrastructure across North America, including early Canadian publications like the Halifax Gazette. The evolution of newspapers is inseparable from the historical impact of print as a communication revolution.

Canada’s first newspaper, the Halifax Gazette, was issued on March 23, 1752, and continues today in a government-issued format (Province of Nova Scotia, 2021). Its longevity underscores print media’s role in official communication, even amid industry shifts (Jobb, 2008).

Debates about newspapers’ decline have intensified, with scholars predicting their eventual extinction due to shifting media consumption and advertising trends (Dawson, 2010; Meyer, 2009). The Pew Research Center (2023) reports U.S. newspaper ad revenue fell from $49.4 billion in 2005 to $8.8 billion in 2020. As Blodget (2009) observes, reactions vary; some see the decline as a crisis, others as a necessary change.

Key questions arise: How do digital advancements reshape journalism? What new funding models will sustain it? How do these shifts impact journalism education, employment, and democratic discourse? (Franklin, 2014). This chapter explores newspapers’ historical evolution, connecting past transformations to contemporary challenges and the future of journalism.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Explain the evolution of news delivery from its earliest forms to modern challenges, identifying key historical developments that have shaped journalism.

- Analyze how audience engagement and distribution systems have influenced newspaper development throughout history.

- Evaluate possible futures for newspapers and journalism in response to technological, economic, and social changes.

- Compare and contrast newspapers’ historical legacy with contemporary news products and consumption patterns, identifying continuities and disruptions.

Early History

Throughout its long and complex history, the newspaper has undergone many transformations, adapting to technological, political, and social changes while maintaining its core information dissemination function. Examining newspapers’ historical roots can help shed light on how and why the newspaper has evolved into the multifaceted medium it is today. Most scholars credit the ancient Romans with publishing the first newspaper, Acta Diurna, or “daily doings,” in 59 BCE. Although no copies of this early publication have survived, historical accounts suggest it published chronicles of events, assemblies, births, deaths, and daily gossip, establishing a template for news content that would persist for centuries (Stephens, 2007).

In 1566, another important ancestor of the modern newspaper appeared in Venice, Italy. The avvisis, or gazettes, were handwritten publications that primarily focused on politics and military conflicts. According to Raymond (2012), their production and distribution represented a significant step toward regular news publication, but they faced a critical limitation. The absence of printing-press technology severely restricted the circulation of these papers, confining their impact to relatively small audiences.

As Chapter 3 noted, Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press in the mid-15th century revolutionized publishing and laid the groundwork for modern journalism. In 1440, Gutenberg invented a movable-type press that permitted the high-quality reproduction of printed materials at a rate of nearly 4,000 pages per day—approximately 1,000 times faster than a scribe working by hand (Eisenstein, 2005). This technological breakthrough dramatically reduced the price of printed materials and, for the first time, made them accessible to a mass market. The printing press transformed the scope and reach of newspapers seemingly overnight, setting the stage for the development of journalism as we understand it today.

According to Stephens (2007), the earliest surviving European printed newspapers date back to 1609, both published weekly in German. One, Relations: Aller Furnemmen, was printed by Johann Carolus in Strasbourg, while the other, Aviso Relations over Zeitung, was likely printed by Lucas Schulte in Wolfenbüttel. To avoid government censorship, these publications deliberately omitted the names of their printing locations. The spread of printed newspapers across Europe was swift, with weeklies emerging in Basel by 1610, Frankfort and Vienna by 1615, Hamburg by 1616, Berlin by 1617, and Amsterdam by 1618.

In the early 17th century, England established regular news publications slower than some of its European counterparts. The first English newspaper, Corante, appeared in 1621, followed by France’s in 1631. However, Amsterdam’s printers, benefiting from the city’s trade networks and relative political and religious tolerance, were already exporting weeklies in French and English by 1620. Italy joined the trend with a printed weekly by 1639, while Spain followed in 1641 (Stephens, 2007).

These early newspapers generally followed one of two primary formats, each reflecting different approaches to news presentation. The first was the Dutch-style corantos, a densely packed two- to four-page paper that prioritized efficiency in both production and reading. The second was the German-style pamphlet, a more expansive 8- to 24-page paper that allowed for more detailed coverage and commentary (Raymond, 2012). Many publishers initially adopted the compact Dutch format. However, as their publications grew in popularity and economic viability, they frequently transitioned to the more prominent German style, responding to reader demand for more comprehensive coverage.

Government Control and Freedom of the Press

Because many of these early publications were subject to strict government regulation, they generally avoided reporting on local news or events that might provoke official censure. However, when civil war erupted in England in 1641, as Oliver Cromwell and Parliament challenged and eventually overthrew King Charles I, citizens naturally turned to local papers to cover these momentous events. In November 1641, a weekly paper titled The Heads of Severall Proceedings in This Present Parliament began focusing on domestic news, reflecting the growing public appetite for information about local political developments (Raymond, 2005). According to Goff (2007), the publication of this paper sparked broader discussion about the freedom of the press. This debate was later articulated most forcefully in 1644 by John Milton in his famous treatise Areopagitica.

Although Milton’s Areopagitica focused primarily on Parliament’s ban on certain books rather than specifically on newspapers, it addressed fundamental principles of press freedom that would have far-reaching implications. Milton criticized the tight regulations on printed content by declaring, “[w]ho kills a man kills a reasonable creature, God’s image; but he who destroys a good book, kills reason itself, kills the image of God, as it were in the eye.” This powerful metaphor equating censorship with murder helped frame freedom of expression as a fundamental right rather than a mere privilege (Dobrée, 2018).

Despite Milton’s emphasis on books rather than newspapers, the treatise profoundly affected printing regulations more broadly. As Keane (2009) argues, newspapers were gradually freed from government control in England, and people began to understand and value the concept of a free press as essential to a functioning society. This philosophical shift would later influence press development throughout the English-speaking world.

Newspapers took advantage of this newfound freedom and began publishing more frequently, expanding their scope and influence. With biweekly publications, papers had additional space to run advertisements and market reports. This development changed the role of journalists from simple observers to active players in commerce, as business owners and investors grew to rely on newspapers to market their products and to help them predict business developments. Once publishers recognized newspapers’ growing popularity and profit potential, they began founding daily publications. In 1650, a German publisher began printing the world’s oldest surviving daily paper, Einkommende Zeitung, and an English publisher followed suit in 1702 with London’s Daily Courant (Conboy, 2004). According to Ward (2015), these daily publications, which employed the relatively new format of headlines and the added visual appeal of illustrations, transformed newspapers into vital fixtures in the everyday lives of citizens, establishing a pattern of regular news consumption that persists today.

Types of Newspapers in Canada and the U.S. (19th Century)

The 19th century saw the development of specialized newspaper types catering to different audiences and interests, reflecting the increasing diversification of society and the growing economic significance of the press. Two significant newspapers emerged in Canada and the United States: mercantile and political papers, each serving distinct purposes and readerships.

Mercantile newspapers were primarily intended for prominent business-minded citizens and focused on commercial information. These publications actively profiled business interests and included content such as advertisements, ship schedules, wholesale product prices, and money conversion tables. They also featured domestic and foreign news, though this information was often dated due to the limitations of information transmission at the time (Rutherford, 1982). According to Fetherling (1990), these papers were relatively expensive, typically priced at 5-6 cents per copy or about $10 per year—a significant sum that limited their readership to the affluent classes. Canadian examples of mercantile newspapers included the Quebec Mercury (established 1805) and the Montreal Herald (established 1811). These publications were crucial in facilitating commerce and informing the business community about developments that might affect their interests.

Political newspapers, by contrast, were intended for audiences with particular political biases and placed political interests at the forefront of their coverage. Their content primarily included political discourses and domestic and foreign news that would interest their politically engaged readership, though like the mercantile papers, this news was often somewhat dated (Kesterton, 1967). Political papers were typically priced similarly to mercantile papers—around 5-6 cents per copy or $10 per year—making them similarly inaccessible to the general population. Canadian examples of political newspapers included Le Canadien (established in 1806) and La Minerve (established in 1826). These publications helped shape political discourse and mobilize support for political movements and parties.

By the mid-1850s in Canada, newspapers were typically aligned with either the Reform movement (which later evolved into the Liberal party) or the Conservative party, reflecting the partisan nature of the press at this time. Keshen and St-Onge (2001) note that the political landscape was such that if a town could support a newspaper, it usually had two—one representing each of the major political factions. However, it is important to note that newspapers were not always perfectly aligned with their parties’ views, as there was a growing push for editorial independence. Joseph Howe’s Novascotian was an early example of a publication that sought to maintain some degree of independence from strict party control, establishing a tradition of journalistic autonomy that would become increasingly important in later years (Beck, 1984).

Technological Advancements and Their Impact

The invention of the telegraph in 1845 by Samuel Morse revolutionized news delivery by making communication separate from transportation (Kielbowicz, 1987, p. 29). Before this innovation, the news could move only as quickly as physical couriers could deliver it—whether by boat, train, horse or on foot. This physical limitation imposed significant delays in news transmission, particularly over long distances. According to Standage (1998), the telegraph overcame this constraint by allowing information to travel nearly instantaneously over vast distances through electrical signals.

Within two decades of its invention, the telegraph became mandatory for newspaper publication, fundamentally altering the speed and scope of news reporting. Blondheim (1994) notes that “News by Wire” quickly became a selling feature for newspapers, allowing them to offer readers much more timely information than possible. This development represents another example of journalism adapting technology to its advantage, a pattern that would repeat throughout the industry’s history with each new technological innovation.

The speed of news delivery changed dramatically after Daniel Craig pioneered using carrier pigeons to deliver news, but the telegraph would soon make even this innovation obsolete. According to Schwarzlose (1989), the increasing speed of news transmission created a need for an organizational structure of newsgathering and delivery, forming cooperative arrangements among newspapers. The industry’s adoption of the telegraph to increase speed led to the creation of the Associated Press, a wire service named after the telegraph wire that carried its dispatches. This organization allowed newspapers to share the costs of gathering news across large geographic areas, making comprehensive coverage economically feasible.

Schudson (1981) explains that the technological constraints of the telegraph also influenced how news stories were written, giving rise to the inverted pyramid structure that remains standard in journalism today. This format places the most critical information, answering the questions of who, what, where, when, and perhaps why, in the lead sentence, followed by the rest of the story in descending order of importance, with the least relevant details at the end. This structure was developed partly because telegraph transmission could be interrupted, making conveying the most critical information essential first. Over time, this format became standard practice in news writing, even as the technological constraints that inspired it disappeared (Lowrey, 2012).

News as a Commodity: Historical Roots

The commodification of news is not a new phenomenon; it has deep historical roots that can be traced back to the earliest days of the newspaper industry. As newspapers began to develop, the need for financial sustainability and profitability led to the commercialization of news content. The intricate relationship between advertising and readership has been fundamental to the economic structure of journalism since its inception. Starr (2005) elaborates on how advertising and newspaper readership have always been interconnected, asserting that newspapers were not merely vehicles for delivering news but also products consumed by readers who, in turn, attracted advertisers. This dual nature of the press, which functions as an information provider and a commercial entity, set the stage for how news would be packaged and distributed.

In the early 19th century, advertising became the dominant revenue stream for newspapers, allowing them to thrive as mass media outlets. Baldasty (1992) demonstrates that advertising revenue has long helped offset the high costs of newspaper production, providing financial stability to the media industry. This model became especially important as newspapers transitioned from niche publications to mass-market products aimed at more significant, diverse audiences. The growing power of advertising led to a shift in editorial practices as newspapers began to tailor their content to appeal to their readers and potential advertisers. In this way, content decisions were often influenced by the desire to attract advertisers, with newspapers focusing on stories that would attract the largest possible audience.

However, this advertising-driven model also introduced tensions between journalistic integrity and financial motivations. Advertisers, eager to reach a broad consumer base, often had preferences that influenced editorial priorities, encouraging newspapers to shift toward entertainment, sensationalism, or politically neutral content. As newspapers sought to balance the demands of advertisers with the need to maintain credibility with readers, this led to an ongoing struggle to retain editorial independence. The pressure to generate revenue often resulted in a compromise between producing high-quality journalism and delivering content that appealed to advertisers’ interests.

The penny press, which emerged in the early 19th century, marked a pivotal shift in the economic model of journalism. Schiller (1981) argues that the advent of the penny press revolutionized the newspaper industry by making newspapers affordable to the working class. The penny press targeted a broader audience, appealing to readers who had previously been excluded from print media due to cost barriers. By reducing the price of newspapers, publishers expanded their readership and increased circulation, making it easier to attract advertising dollars. This created a new form of mass communication that allowed for the widespread dissemination of news and introduced new editorial strategies. Sensational stories, often involving scandal and drama, became a key feature of the penny press as publishers learned that such content could captivate audiences and keep them coming back for more.

As the penny press grew in influence, the market for sensational content expanded, giving rise to what would later be known as “yellow journalism.” Yellow journalism, a term coined in the late 19th century, represented a further shift toward sensationalism, with newspapers increasingly focusing on exaggerated and often fabricated stories to capture readers’ attention. Campbell (2003) notes that yellow journalism was characterized by bold headlines, lurid stories, and a tendency to prioritize drama over accuracy. Yellow journalism appealed to a public eager for entertainment and novelty and thrived on scandalous topics like crime, political corruption, and celebrity gossip. In their quest to outdo one another and maximize circulation, publishers resorted to increasingly dramatic tactics, such as hyperbole and sensationalized visuals.

The impact of yellow journalism extended beyond the newspaper industry, influencing the public’s expectations of news and shaping the way journalism was practiced. Newspapers competing for readers’ attention often made editorial compromises, prioritizing sensational stories over traditional journalistic values such as factual accuracy and objectivity. While yellow journalism may have been profitable in the short term, it also fostered a lasting tension between sensationalism and responsible journalism. This conflict continues to shape today’s media landscape.

Reform Journalism and Muckraking

In contrast to the rise of sensationalism, another important tradition emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries: reform-oriented journalism, often referred to as “muckraking.” The muckraking tradition was rooted in a desire to expose societal injustices, corruption, and exploitation, particularly within business and politics. Journalists associated with muckraking sought to use their investigative skills to bring about social change by exposing the hidden truths of powerful institutions. Muckrakers like Henry Demarest Lloyd, whose 1881 work Wealth Against Commonwealth exposed the monopolistic practices of corporations, and Ida B. Wells, who documented the rampant violence and injustice faced by African Americans through her anti-lynching campaigns, exemplified the role of the press in advocating for reform (Weinberg & Weinberg, 2001). These journalists were driven by a commitment to uncovering the truth and believing that exposing societal ills could lead to meaningful change.

Aucoin (2007) explains that the muckraking tradition evolved in two significant ways. On one hand, it produced high-profile investigations that led to substantial political and social changes, such as the reporting that exposed the Watergate scandal and ultimately led to the resignation of U.S. President Richard Nixon. This type of investigative journalism showcased the power of the press to hold the government accountable and to act as a check on political corruption. On the other hand, muckraking’s investigative practices, which had been initially aimed at reform, contributed to the rise of tabloid journalism, where the line between fact and entertainment often blurred. Covering private scandals, especially involving public figures, became a staple of specific publications as media outlets learned that such stories could attract large audiences and generate significant profits.

Feldstein (2006) argues that this dual legacy of muckraking, both as a force for reform and as a precursor to tabloid-style journalism, illustrates the complex and contradictory nature of the press. While muckrakers played a crucial role in exposing social injustices and holding influential figures accountable, the same techniques they employed in their investigations also contributed to the commercialization of news. The growing demand for sensational stories and the increasing pressure to sell newspapers led some muckrakers to focus more on sensationalized gossip and private information, which helped foster the culture of celebrity journalism that has become ubiquitous in modern media.

Despite the commercialization of muckraking, its legacy remains an essential part of modern journalism. Investigative journalism remains a vital part of the journalistic landscape, particularly in an age of corporate consolidation and government oversight. As Feldstein (2006) points out, while sensationalism and entertainment-driven news may dominate many aspects of the media, investigative reporting remains central to the public’s understanding of complex issues and the media’s function as a watchdog for democracy. The ethical challenges modern investigative journalists face, balancing the public’s right to know with the potential harm caused by sensationalized coverage, are directly linked to the historical development of muckraking and its impact on the profession.

The Canadian Perspective

The development of newspapers in Canada followed a somewhat different trajectory than in the United States, shaped by the country’s unique social, political, and geographic conditions. Unlike the rapid commercialization of newspapers in the U.S., where mass-circulation dailies emerged in major cities by the early 19th century, Canada’s press gradually evolved, influenced by lower population density, linguistic diversity, and strong ties to British colonial governance.

The first printing press was introduced to Canada in 1751 by John Bushell, leading to the publication of the Halifax Gazette, the country’s first newspaper (Desbarats, 1989). Initially, growth was slow due to limited literacy rates, small urban populations, and the logistical challenges of transporting newspapers across vast and sparsely populated territories. By 1815, there were approximately 20 newspapers in operation, reaching a combined readership of around 2,000 (Rutherford, 1982). However, as literacy rates improved and European immigration increased, demand for newspapers grew significantly. By 1850, nearly 300 newspapers were published nationwide, reflecting a shift toward a more engaged reading public and expanding settlement patterns (Rutherford, 1982).

Before 1900, newspapers in Canada were primarily considered “small-town” enterprises, with a strong local focus and relatively modest circulation numbers (Kesterton, 1967). Unlike in the United States, where major urban centers such as New York and Chicago developed prominent daily newspapers early on, Canada’s press was shaped by the country’s decentralized population and the challenges of distributing newspapers across long distances. Many newspapers were closely aligned with political parties, serving as platforms for partisan debate rather than neutral news sources. This practice was particularly evident in publications such as Le Canadien (1806) and La Minerve (1826), which actively promoted nationalist and reformist ideologies in Lower Canada (now Quebec).

Despite these challenges, newspapers were crucial in fostering community cohesion and shaping regional and national identities. As Fetherling (1990) notes, local newspapers were often central to town life, reporting on civic affairs, social events, and political developments that directly impacted their readership. They also served as instruments of nation-building, particularly in the decades leading up to Confederation in 1867, by providing a platform for debates on governance, trade, and cultural identity. By the late 19th century, newspapers in Canada had become essential to public discourse, covering domestic politics, international events, economic trends, and emerging social movements.

With technological advancements, such as the telegraph and railway expansion, improved communication networks, newspapers could broaden their coverage and reach broader audiences. This shift laid the groundwork for the rise of influential urban newspapers, such as The Globe and Mail in Toronto (1844) and The Montreal Gazette (1778), shaping Canadian journalism well into the 20th century.

Comics and Stunt Journalism

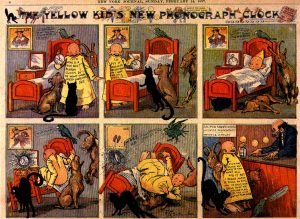

As publishers competed intensely for readership in the late 19th century, an entertaining new element was introduced to newspapers: the comic strip. Initially, newspaper content had been dominated by text-heavy articles, political commentary, and advertisements. However, as literacy rates increased and mass media became more commercialized, publishers sought new ways to engage a broader audience, including working-class and immigrant readers. This shift led to the rise of illustrated storytelling, which offered visual entertainment alongside traditional news content.

A breakthrough in this genre occurred in 1896, when William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal published R. F. Outcault’s The Yellow Kid. The comic strip featured a mischievous child in a distinctive yellow nightshirt, speaking in working-class slang. The character and its humorous, exaggerated style captivated audiences, particularly among immigrant communities, who found it accessible despite language barriers (Yaszek, 1994). The Yellow Kid became a cultural phenomenon, sparking what Yaszek (1994) described as a wave of “gentle hysteria” (p. 30). The character’s likeness soon appeared on consumer products, including buttons, cracker tins, cigarette packs, and even ladies’ fans, demonstrating its broad commercial appeal. The popularity of The Yellow Kid was so immense that it even inspired a Broadway play.

Alongside the rise of comics, another development in journalism during this era was the advent of “stunt journalism,” a form of investigative reporting that involved journalists, often women, undertaking daring assignments to expose social injustices. One of the most famous figures in this movement was Nellie Bly, who gained national fame for her exposé on the conditions of mental institutions after going undercover as a patient at the Women’s Lunatic Asylum on Blackwell’s Island in 1887. Her work, published in The New York World, led to public outrage and policy reforms (Lutes, 2002). This form of journalism, like comics, played a key role in broadening newspapers’ appeal and social impact, making them a more dynamic and influential force in society.

Through the emergence of comics and stunt journalism, newspapers in the late 19th century evolved from dry, text-heavy publications into more visually engaging and socially impactful media. This period marked a shift in how news was consumed, making it more accessible to diverse audiences and setting the stage for the modern mass media landscape.

Key Figures in Newspaper History

Several key figures stand out in newspaper history for their contributions to the development of journalism and its role in society. These individuals shaped the press through investigative reporting, political advocacy, and innovations in publishing, leaving lasting legacies in the field.

One of the most influential early Canadian journalists was Joseph Howe, who began his career at just 23 years old when he purchased the Novascotian in 1827 (Beck, 1984)*. Unlike many newspapers of the time, which were closely aligned with political parties, Howe sought to establish his paper as an independent voice dedicated to public accountability. In 1835, he published a letter exposing corruption among local judges and police, leading to a major political scandal. When he was charged with libel for his publication, no lawyer was willing to take his case, forcing him to defend himself in court. According to Beck (1984), Howe’s impassioned self-defence and ultimate acquittal set a crucial legal precedent for press freedom in Canada, reinforcing the right of journalists to challenge government authorities without fear of persecution. His success in journalism propelled him into politics, where he continued to champion democratic reforms and free speech.

Another pioneering journalist was Maisie Hurley (1887–1964), a tireless advocate for Indigenous rights in Canada. Alongside her husband, lawyer Tom Hurley, she worked to defend First Nations peoples in British Columbia against legal injustices. Recognizing the need for a platform to amplify Indigenous voices, Hurley founded Native Voice in 1946, the first Aboriginal newspaper in Canada (Jamieson, 2016). The publication quickly gained an international readership, attracting the attention of political figures such as future Prime Minister John Diefenbaker. Native Voice became a powerful tool in the fight against discriminatory policies, including the Indian Act and the residential school system. Hurley’s journalism was informative and activist, using the press to challenge colonial oppression and advocate for Indigenous voting rights.

Beyond Howe and Hurley, other key figures in newspaper history include:

Joseph Pulitzer (1847–1911), a Hungarian-American newspaper publisher, transformed journalism through investigative reporting and mass-market appeal. His New York World set new standards for sensational storytelling while advancing social reform journalism. Pulitzer’s work in the late 19th and early 20th centuries established a new model for newspapers, combining bold headlines, investigative journalism, and an appeal to mass audiences. His legacy includes the Pulitzer Prizes, which continue to recognize excellence in journalism (Juergens, 2015).

William Randolph Hearst (1863–1951) was the media magnate behind the New York Journal, known for popularizing yellow journalism and shaping early tabloid-style reporting. Hearst used sensationalism and scandalous stories to attract readers, often using exaggerated headlines and lurid details to increase circulation. His impact on American journalism was profound, as he helped create a press environment that prioritized entertainment and sensationalism, setting a precedent for the following tabloid journalism (Whyte, 2009).

These figures exemplify the transformative power of journalism, demonstrating how newspapers have served not only as sources of information but also as platforms for activism, social change, and political engagement. Their work laid the foundation for modern journalism, shaping the ethical debates and journalistic standards that continue to influence media today.

Today and Looking Forward

Based on historical trends, the gathering of news (by journalists), its delivery (through technology), and its consumption (by readers) will continue to merge and evolve, creating new forms and practices of journalism. The digital age has accelerated these transformations, profoundly reshaping how news is produced, distributed, and consumed. As traditional media outlets contend with rapid technological advancements, online platforms increasingly dominate journalism, marking a decisive shift from print to digital. This transformation has not only affected the way content is delivered but also how it is consumed. The rise of mobile devices, social media, and digital subscription models has led to more personalized and instantaneous access to news. According to Newman et al. (2024), this digital shift has been accompanied by significant changes in advertising revenue models, where traditional print media has seen a dramatic decline in advertising income, while online platforms have experienced a surge in digital advertising dollars, which has become a primary revenue source. This challenge to the economic sustainability of traditional journalism organizations has prompted them to rethink their business models and explore alternative sources of revenue, such as paid subscriptions and partnerships with digital platforms.

In the face of these changes, traditional media organizations strive to coexist with social media platforms by adopting hybrid models that blend professional journalism with user-generated content. This evolving dynamic is reflected in a broader trend of convergence, wherein the lines between professional and citizen journalism are becoming increasingly blurred. Hermida et al. (2012) argue that this adaptation is part of journalism’s long-standing ability to incorporate new technological innovations while retaining its core functions—gathering, verifying, and disseminating information. Integrating social media and user-generated content within professional news outlets reflects both the opportunities and challenges the digital era poses. On one hand, these new models provide increased engagement and the democratization of information sharing, while on the other hand, they raise concerns about the quality and accuracy of news.

One of the most significant challenges in journalism today is the increasing role of non-journalists in news creation and distribution. Social media platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube allow anyone with internet access to share information, often without adhering to traditional journalistic principles like fact-checking and editorial oversight. As Rusbridger (2018) notes, this shift raises concerns about the future of reliable news, not just in changing business models but in how journalism is defined. The spread of misinformation and disinformation by individuals outside professional news organizations threatens the accuracy of the information people rely on to make informed decisions in democratic societies.

To explore these issues further, you are encouraged to visit MRUnderstanding Misinformation, Mount Royal University’s interactive e-learning resource. This engaging platform provides lessons, activities, and tools to help you identify, analyze, and respond to misinformation, including fake news, disinformation, and malinformation. It also covers propaganda, conspiracy theories, and their appeal, along with the impact of misinformation on Indigenous communities. Additional modules focus on evaluating news, science, and social media content for accuracy and how journalists verify claims using digital tools. This resource supports the development of critical media literacy skills essential for participating in democratic communication with care, curiosity, and credibility.

Furthermore, as technology continues to evolve, the future of journalism will likely involve an increased reliance on artificial intelligence (AI) and automation in news production. These technologies can revolutionize newsroom operations by automating data analysis, fact-checking, and content creation. While AI can enhance journalistic efficiency, it also raises questions about the ethics of automated news generation, potential job displacement, and the preservation of journalistic integrity. How journalism adapts to these technological advances—balancing innovation with ethical standards—will determine its role in society.

In the coming years, journalism must navigate these challenges while remaining committed to its fundamental mission: providing citizens with accurate, timely, and fair information. As the media landscape becomes increasingly fragmented, the need for trusted and reliable news sources will only grow, underscoring the importance of maintaining journalistic standards in rapid technological change.

Summary

The history of newspapers reveals a medium defined by continuous adaptation and reinvention. From ancient Rome’s Acta Diurna to today’s digital platforms, journalism’s core function, providing society with reliable information, has remained constant while its forms have transformed. This adaptability offers valuable context for understanding today’s challenges.

Key Takeaways

Key takeaways from this chapter include:

- Journalism has always been shaped by technological disruption. The printing press, telegraph, and now digital media each prompted existential questions about newspapers’ survival, yet journalism adapted each time by incorporating new technologies while preserving its essential purpose.

- The tension between commercial viability and public service has been a constant struggle. From partisan funding to advertising dependency to today’s search for sustainable digital models, the economic foundations of journalism have always been precarious.

- Journalism’s relationship with power continues to define its societal role. Whether challenging authorities through investigative reporting or serving established interests, this fundamental tension persists in the digital age.

Looking ahead, newspapers face profound challenges: collapsing business models, platform dominance, and AI automation. Yet history suggests journalism will persist, albeit in transformed ways. The social need for verified information remains vital in an era of misinformation.

As we navigate this transition, understanding newspapers’ historical evolution provides context and confidence that journalism will continue to fulfill its essential democratic function, even as its forms evolve.

Group Activity: Headline Time Machine

Travel back in time and step into the shoes of historical journalists. Your group will recreate a significant newspaper moment based on key events from the chapter while deciding how to frame the story for different audiences.

Instructions:

- Pick a Historical Event – Each group will draw a slip of paper (or choose from a list) featuring a significant moment in newspaper history (e.g., the launch of the Halifax Gazette in 1752, the rise of the Penny Press, Joseph Howe’s libel trial, or the introduction of the telegraph to news reporting).

- Create Two Headlines – Your group must write two contrasting newspaper headlines for the event:

- One from a sensationalist/yellow journalism perspective

- One from a serious, fact-based journalism perspective

- Write a News Excerpt – In 3–4 sentences, draft the beginning of each article, reflecting the style of each approach.

- Present to the Class – Each group will share its two headlines and excerpts. The class will discuss how journalistic framing influences public perception of historical events.

Debrief Discussion:

- How do sensationalized vs. factual reporting styles shape public opinion?

- What impact did newspapers have on historical events?

- If social media had existed during this time, how might these events have been reported differently?

Bonus Challenge: If time allows, assign one group to serve as a panel of historical editors who decide which story will be published!

End-of-Chapter Activity (News Scan)

Newspaper Evolution in the Digital Age

Purpose: This assignment helps you connect historical perspectives on newspaper evolution with contemporary developments, enhancing your ability to critically analyze media trends and industry transformations through historical and current lenses.

Using Google News, find a recent article (published in the last three months) about the current state, challenges, or innovations in newspaper journalism in Canada or globally.

In 250 words, respond to the following:

- Summarize the Article (100-150 words)

- Provide the title, author, and date in APA format.

- Explain the article’s primary focus and significance.

- Identify key findings or arguments presented.

- Connect to Chapter Themes (100-150 words)

- Relate the article to at least one key theme from this chapter (such as technological disruption, business model evolution, journalistic practices, or the social role of newspapers).

- Analyze how the article illustrates continuity or change in the newspaper industry compared to historical patterns discussed in the chapter.

- Explain what the article suggests about the future trajectory of newspapers.

Cite your sources (textbook and article) in APA format.

Note: The full text of the article must be included upon submission as an Appendix for verification.

References

Aucoin, J. L. (2007). The evolution of American investigative journalism. University of Missouri Press.

Baldasty, G. J. (1992). The commercialization of news in the nineteenth century. University of Wisconsin Press.

Beck, J. M. (1984). Joseph Howe: Conservative reformer. McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Blodget, H. (2009, March 15). How people feel about the death of newspapers. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/henry-blodget-how-people-feel-about-the-death-of-newspapers-2009-3

Blondheim, M. (1994). News over the wires: The telegraph and the flow of public information in America, 1844-1897. Harvard University Press.

Campbell, W. J. (2003). Yellow journalism: Puncturing the myths, defining the legacies. Praeger.

Clarke, C. E. (1994). The public prints: The newspaper in Anglo-American culture, 1665-1740. Oxford University Press.

Conboy, M. (2004). Journalism: A critical history. Sage.

Dawson, R. (2010). Newspaper extinction timeline. Ross Dawson Blog.

Desbarats, P. (1989). Guide to Canadian news media. Harcourt Brace.

Dobrée, B. (2018). Milton’s “Areopagitica” in the twenty-first century. Cambridge University Press.

Eisenstein, E. L. (2005). The printing revolution in early modern Europe (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Feldstein, M. (2006). A muckraking model: Investigative reporting cycles in American history. Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics, 11(2), 105-120.

Fetherling, D. (1990). The rise of the Canadian newspaper. Oxford University Press.

Franklin, B. (2014). The future of journalism in an age of digital media and economic uncertainty. Journalism Studies, 15(5), 481–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2014.930254

Goff, M. (2007). Early history of the English newspaper. 17th-18th Century Burney Collection Newspapers. Gale.

Hermida, A., Fletcher, F., Korell, D., & Logan, D. (2012). Share, like, recommend: Decoding the social media news consumer. Journalism Studies, 13(5-6), 815–824.

Jamieson, E. (2016). The Native Voice: The story of how Maisie Hurley and Canada’s first Aboriginal Newspaper changed a nation. Caitlin Press.

Jobb, D. (2008). “Creating Some Noise in the World”: Press Freedom and Canada’s First Newspaper, the Halifax Gazette, 1752-1761 [Doctoral dissertation, Saint Mary’s University, Halifax].

Juergens, G. (2015). Joseph Pulitzer and the New York World. Princeton University Press.

Keane, J. (2009). The life and death of democracy. Simon & Schuster.

Keshen, J., & St-Onge, N. (2001). Ottawa: Making a capital. University of Ottawa Press.

Kesterton, W. H. (1967). A history of journalism in Canada. McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Kielbowicz, R. B. (1987). News gathering by mail in the age of the telegraph: Adapting to a new technology. Technology and Culture, 28(1), 26-41.

Library and Archives Canada. (2007). The last best West: Advertising for immigrants to western Canada, 1870–1930. https://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/west/

Lowrey, W. (2012). Journalism innovation and the ecology of news production: Institutional tendencies. Journalism & Communication Monographs, 14(4), 214–287.

Lutes, J. M. (2002). Into the madhouse with Nellie Bly: Girl stunt reporting in late nineteenth-century America. American Quarterly, 54(2), 217–253.

Meyer, P. (2009). The vanishing newspaper: Saving journalism in the information age (2nd ed.). University of Missouri Press.

Nerone, J. (2015). The media and public life: A history. Polity.

Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Robertson, C. T., Ross Arguedas, A., & Nielsen, R. K. (2024). Reuters Institute digital news report 2024. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

Pew Research Center. (2023). State of the news media. https://www.pewresearch.org/topics/state-of-the-news-media/

Province of Nova Scotia. (2021). Royal Gazette. https://archives.novascotia.ca/gazette/

Raymond, J. (2005). The invention of the newspaper: English newsbooks, 1641–1649. Oxford University Press.

Raymond, J. (2012). News networks in seventeenth-century Britain and Europe. Routledge.

Rusbridger, A. (2018). Breaking news: The remaking of journalism and why it matters now. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Rutherford, P. (1982). A Victorian authority: The daily press in late nineteenth-century Canada. University of Toronto Press.

Schiller, D. (1981). Objectivity and the news: The public and the rise of commercial journalism. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Schudson, M. (1981). Discovering the news: A social history of American newspapers. Basic Books.

Schwarzlose, R. A. (1989). The nation’s newsbrokers: The formative years, from pretelegraph to 1865 (Vol. 1). Northwestern University Press.

Standage, T. (1998). The Victorian Internet: The remarkable story of the telegraph and the nineteenth century’s on-line pioneers. Walker & Company.

Starr, P. (2005). The creation of the media: Political origins of modern communications. Basic Books.

Stephens, M. (2007). A history of news (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Ward, S. J. A. (2015). The invention of journalism ethics: The path to objectivity and beyond (2nd ed.). McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Weinberg, A., & Weinberg, L. (2001). The muckrakers. University of Illinois Press.

Whyte, K. (2009). The uncrowned king: The sensational rise of William Randolph Hearst. Catapult.

Yaszek, L. (1994). ‘Them damn pictures’: Americanization and the comic strip in the Progressive Era. Journal of American Studies, 28(1), 23–38.