3 Chapter 3: The Printing Press

Amanda Williams

Introduction

The printing revolution transformed human communication, reshaping how societies exchanged ideas and preserved knowledge. With printed materials replacing hand-copied manuscripts, information access expanded dramatically, democratizing knowledge previously restricted to elites. While many innovations have influenced history, the printing press stands out for its profound impact on literacy, cultural exchange, and the fundamental ways civilizations share their collective wisdom.

This chapter explores the history of the printing press in the world and Canada, its role in transforming society, and its continued relevance in today’s world. Before Gutenberg’s invention, books were painstakingly copied by hand on materials like clay, papyrus, and parchment. With the advent of the printing press, books became more accessible, and by the mid-1500s, millions of printed books existed, compared to just a handful of handwritten volumes (Lienhard, 1998).

Although Gutenberg is often credited with inventing the press, it is important to recognize that his work built on previous ideas and innovations. His contribution was refining the technology, making it commercially viable, and enabling the mass production of printed materials that revolutionized communication (Chappell, 2011). The spread of printing in Canada began nearly 300 years later, driven by missionaries, business owners, and newspaper publishers (Scanlon, 2018). This chapter will examine the lasting impact of print on how we communicate and preserve knowledge.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Identify the dynamics associated with the early formation of print until its popularization.

- Recognize that popularizers and inventors may differ in historical media development accounts.

- Assess the printing press’s continued legacy.

From Orality to Print: The Evolution of Communication

The transition from oral traditions to literacy fundamentally reshaped human communication, but the next major shift, the rise of print, further accelerated societal transformations. While writing allowed for the preservation and expansion of knowledge, the ability to mass-produce texts through the printing press introduced unprecedented possibilities for dissemination, education, and political change. No longer constrained by the limitations of oral transmission or the slow reproduction of manuscripts, print revolutionized how knowledge was stored, shared, and contested across societies.

However, the development of print was not instantaneous. It emerged gradually, requiring key technological innovations, economic shifts, and social adaptations. While Johannes Gutenberg is often credited with inventing the printing press, the reality is more complex; printing technologies have existed for centuries in various forms, particularly in East Asia. Gutenberg’s contribution was not the invention of printing itself but the refinement and commercialization of movable type technology, making it economically viable and widely accessible (Eisenstein, 1983).

The impact of print extended far beyond technological innovation. Its widespread adoption led to religious reform, scientific collaboration, political revolution, and the emergence of mass literacy. It challenged existing power structures, reshaped how knowledge was produced and controlled, and laid the foundation for the modern information age.

The Predecessors of Print: Innovations Before Gutenberg

Chapter 2 notes before the printing revolution transformed Western society, human civilizations relied primarily on oral communication and hand-copied manuscripts to transmit knowledge. Writing had allowed civilizations to store information more permanently than speech, but written texts remained labour-intensive and prohibitively expensive, making literacy a privilege reserved for elites (Clanchy, 2013). Manuscript culture, with its beautiful but time-consuming illuminations and calligraphy, ensured that books remained luxury items, often chained to library desks or locked in monastic collections.

In the centuries before Gutenberg’s press emerged in Europe, several printing techniques had already been developed across different world regions. Woodblock printing arose in China during the 7th to 9th centuries CE. In this method, text and images were meticulously carved into wooden blocks, inked, and pressed onto paper. The Diamond Sutra, produced in 868 CE, is the world’s oldest surviving printed book and demonstrates the sophisticated nature of Chinese printing technology (Shi, 2010). The intricate Buddhist text showcases the technical capabilities of the artisans who created it and the religious and cultural significance attached to book production in East Asia (Huang, 2011).

Korean innovations pushed printing technology further with the development of movable type in the 13th century CE. Unlike woodblocks, which required entirely new carvings for each page, this ingenious technique employed individual metal characters that could be rearranged to form different pages. The Jikji, a Buddhist text printed in Korea in 1377, predates Gutenberg’s European work by over 70 years, challenging Eurocentric narratives about the origins of printing technology (Kim, 2010).

Beyond East Asia, printing developments occurred in other regions as well. Ancient Egyptians employed carved wooden stamps to imprint designs on clay and later papyrus as early as 3000 BCE. However, these were primarily used for decorative and administrative purposes rather than textual reproduction (Woods & Woods, 2011). By the 6th century CE, Byzantine craftspeople had adapted block printing techniques primarily for decorative textiles and religious imagery before incorporating them into manuscript production (Brubaker & Haldon, 2017).

The Islamic world significantly contributed to the preconditions for print culture during the 9th and 10th centuries CE. While religious considerations led many Muslim scholars to reject image reproduction, they developed sophisticated manuscript production systems and paper manufacturing techniques that would later support European printing (Bloom, 2001). The paper-making skills that spread westward from the Islamic world proved essential to Gutenberg’s later success. European parchment would have been too costly and unsuitable for his mechanical press.

Despite these regional advancements, printing remained limited in its societal impact for centuries. Several factors contributed to this delayed diffusion. The complex logographic nature of Chinese and Korean scripts, with thousands of unique characters, made the transition to movable type less economically advantageous than it would later prove for alphabetic writing systems (Febvre & Martin, 1976). Additionally, the lack of widespread economic demand for mass-produced books meant that print technology remained confined mainly to official government and religious institutions.

Social factors further constrained the spread of early printing technologies. Scribes and illuminators formed powerful guilds that actively resisted mechanical reproduction, seeing it as a threat to their livelihoods and craftsmanship (De Hamel, 1992). Material limitations presented practical challenges, as early paper quality varied significantly, and production capacity could not support truly mass printing enterprises. Perhaps most fundamentally, manuscript culture was deeply embedded in religious and scholarly traditions, with hand-copied texts considered more authentic and prestigious. These cultural attitudes must shift before print can achieve its revolutionary potential.

Gutenberg’s Innovations: The Key to Print’s Expansion

Johannes Gutenberg’s success lay not in the invention of printing itself but in his ability to create a scalable and profitable system that specifically addressed the needs of European markets and writing systems. His genius resided in combining existing technologies into a revolutionary whole, an innovation pattern that reappeared throughout media history (Eisenstein, 1983). Gutenberg’s system included several critical components, transforming textual reproduction’s economics and capabilities.

Chief among his contributions was the development of durable metal movable type (a reusable system optimized for the Latin alphabet’s relatively limited character set). Unlike earlier Asian systems that needed to accommodate thousands of different characters, Gutenberg’s approach allowed for faster and cheaper text reproduction with fewer individual pieces. His metallurgical expertise was crucial here; he developed alloys that could withstand repeated use while maintaining crisp letter forms (Bigelow, 2018).

Gutenberg’s type-casting method represented another breakthrough. He developed a precise system using punches, matrices, and a hand mould that allowed for consistent letter production with unprecedented speed. This standardization was essential for creating visually uniform pages that could rival the aesthetic quality of manuscripts. The composing stick and type case he introduced provided organizational tools that streamlined the typesetting process, allowing printers to arrange letters efficiently (Man, 2009).

The oil-based ink Gutenberg formulated marked another significant advance. Unlike the water-based inks used in Asia and by manuscript illuminators, his formulation adhered better to metal type, ensuring more precise, consistent prints that could be produced on both sides of a page without bleed-through. This seemingly minor technical detail proved essential for producing durable, readable texts at scale (The Morgan Library & Museum, n.d).

Equally important was Gutenberg’s adaptation of the screw press. By modifying technology previously used for wine and olive oil production, he created a device that could apply uniform pressure for efficient printing across the entire page (Berne, 2024). His registration system, ensuring accurate alignment between pages and during two-colour printing, added another level of quality control that made printed books more visually appealing to readers accustomed to manuscript aesthetics (Lehmann-Haupt, 1966).

Beyond these technical innovations, Gutenberg pioneered business models that would shape publishing for centuries. His partnerships with investors like Johann Fust created a template for future print businesses, demonstrating how capital investment could be harnessed to support media production. This financial innovation was as important as his mechanical ones, providing a sustainable economic foundation for the industry’s growth (Füssel, 2020).

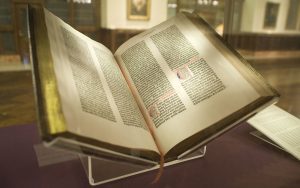

Gutenberg’s first significant work, the 42-line Bible, was completed around 1455 and demonstrated technical mastery and commercial insight. Gutenberg created a hybrid product that bridged old and new media forms by mimicking the aesthetic standards of luxury manuscripts while significantly reducing production costs (Füssel, 2020). This approach proved critical to print’s initial acceptance among educated elites, who valued the traditional appearance of books and the economic advantages of the new technology. Although Gutenberg himself would be financially ruined through legal disputes with his investors before he could fully capitalize on his invention, his technological system laid the groundwork for a communication revolution that would unfold across Europe in the coming decades.

The Slow Rise of Print: How Popularization Took Hold

Contrary to popular narratives of immediate transformation, the printing revolution unfolded slowly over generations. In the early years after Gutenberg, printing was primarily used for religious texts and legal documents. The first books were produced in Latin, catering to the same elite circles that had controlled manuscript culture. Printers initially mimicked manuscript conventions, sometimes even leaving spaces for hand illumination, demonstrating how media transitions often blend old and new forms before establishing their own conventions (Eisenstein, 1983).

Over time, however, print expanded into new domains, reshaping intellectual and social life. Religious reform movements provided one of the most consequential channels for print’s influence. The mass production of vernacular Bibles allowed ordinary people to engage directly with scripture for the first time, challenging the Church’s monopoly on biblical interpretation. Martin Luther’s strategic use of print media to disseminate his critiques of Catholic practice demonstrated how the new technology could rapidly spread ideas beyond institutional control.

Scientific exchange was transformed as scholars could publish and debate ideas across Europe with unprecedented precision and speed. Standardizing diagrams, mathematical notation, and experimental reports accelerated the Scientific Revolution by enabling more rigorous comparison and verification of claims. Copernicus, Vesalius, and later Galileo depended on print’s capabilities to challenge established knowledge and advance new understanding of the natural world (Johns, 2000).

The expansion of vernacular literature brought reading to wider audiences. Printing popular stories and poems in local languages broadened literacy beyond Latin-educated elites. Works like Cervantes’ “Don Quixote” reached thousands of readers across social classes, creating new forms of shared cultural reference. This democratization of reading transformed how people understood themselves and their societies (Chartier, 2019).

Practical knowledge found new pathways to dissemination through print. Manuals on agriculture, navigation, and crafts served growing middle-class needs and practical applications. These texts often combined visual and verbal information in novel ways, creating new forms of instructional communication. A farmer could learn techniques previously transmitted only through direct apprenticeship, while navigators could carry standardized charts on long voyages (Fisher, 2022).

Visual culture underwent its own revolution. The reproduction of maps, anatomical drawings, and botanical illustrations standardized visual knowledge and created new forms of expertise. Scientific illustrators developed specialized techniques for representing knowledge visually, while map-makers could update and correct geographic information with each new printing. These developments fundamentally altered how knowledge was organized and understood (Ivins, 1969).

Political discourse evolved as print enabled the formation of a “public sphere.” The rise of pamphlets and, eventually, newspapers allowed political ideas to be contested more freely and widely. During periods of conflict like the English Civil War or the American Revolution, print became a battleground for competing visions of society. These printed debates laid the groundwork for modern democratic participation by making political arguments accessible beyond courtly and ecclesiastical circles (Pettegree, 2014).

Economic factors played a crucial role in this gradual expansion. The growth of paper manufacturing throughout Europe lowered production costs, making printed materials increasingly affordable. Distribution infrastructure improved as new roads, postal services, and merchant networks facilitated the movement of books and periodicals across regions. Urban growth created concentrated populations with rising literacy rates, providing sustainable markets for printed works (Briggs & Burke, 2009).

Commercial networks revolved around print shops and became nodes in international exchange, creating new patterns of cultural transmission. Book fairs in Frankfurt, Lyon, and Venice became crucial meeting points where ideas and texts circulated among publishers, scholars, and merchants. These networks allowed innovations in both content and form to spread rapidly among printers, accelerating the medium’s evolution (Maclean, 2012).

This expansion of print’s influence demonstrates an important principle of media revolutions: technological change alone does not drive societal transformation. Social, economic, and cultural factors must align for a medium’s full impact to unfold. The printing press did not immediately revolutionize European society; it required time, adaptation, and investment before its revolutionary potential was realized.

Recognizing the Role of Popularizers in Media History

The story of the printing revolution highlights an important distinction in media history: the difference between inventors (those who create a technology) and popularizers (those who expand its reach and social significance). Although Gutenberg’s press was technologically groundbreaking, it was not an immediate commercial success. The true revolution came through the efforts of numerous figures who adapted, refined, and extended print technology to serve diverse social needs.

Aldus Manutius, working in Venice during the late 15th and early 16th centuries, transformed publishing through several innovations. He introduced small, portable octavo books—precursors to modern paperbacks—that made print affordable for a broader audience. His development of italic typefaces saved space and created new aesthetic possibilities for printed text. Manutius also established standards for scholarly editions of classical texts that balanced accuracy with accessibility, creating new markets for humanist learning (Davies, 1995).

William Caxton established the first English printing press in 1476 and played a pivotal role in standardizing English. His decisions about which dialect forms to print helped consolidate linguistic practices at a crucial moment in English development. By printing works like Chaucer’s “Canterbury Tales” and Malory’s “Le Morte d’Arthur,” Caxton helped establish a national literary canon that would shape English cultural identity for centuries (Blake, 1991).

Martin Luther’s relationship with print exemplifies how technology became a tool for religious and social reform. Beyond his German Bible translation, Luther published numerous pamphlets and broadsides designed for rapid circulation among ordinary readers. His strategic use of woodcut illustrations and vernacular language demonstrated print’s power to influence public discourse across social classes. The circulation of Lutheran texts created new reading practices and forms of religious community organized around printed materials (Matheson, 1998).

Often overlooked in traditional histories, women printers significantly contributed to the medium’s development. Charlotte Guillard in Paris and the women of the Wechel family maintained and expanded printing businesses after their husbands’ deaths, often specializing in scientific and medical texts that required particular technical skills. Their persistence demonstrated how print could create new professional opportunities even within the constraints of early modern gender norms (Broomhall, 2018).

These popularizers’ business models were just as important as their printed content. Subscription models pre-financed books through wealthy patrons or subscriber lists, distributing risk and ensuring market interest before production. Serial publications created sustainable revenue through periodical publications, establishing regular reading habits supporting newspaper culture (Glover, 2012). Early attempts to protect intellectual property evolved into modern copyright concepts, balancing creator incentives with knowledge circulation.

This distinction between invention and popularization is crucial in understanding why some technologies succeed while others fail. Many innovations remain marginal until they are integrated into broader social and economic systems. Gutenberg’s press required these networks of popularizers—printers, editors, booksellers, and readers—to realize its revolutionary potential. Their collective efforts transformed a mechanical invention into a social institution that would reshape knowledge transmission for centuries.

Assessing Gutenberg’s Continued Legacy

Gutenberg’s printing system laid the foundation for modern mass communication. His innovations created a blueprint for knowledge distribution that remains evident in today’s digital and networked media. Understanding this legacy helps us recognize the precedents for our media environment and the patterns of technological adoption that might shape future communication systems.

The religious impact of print proved profound and multifaceted. Print weakened centralized ecclesiastical control by enabling broader access to religious texts and enabled individuals to engage directly with scripture. This shift undermined the Church’s interpretive monopoly and contributed to the fragmentation of Western Christianity during the Reformation. However, religious institutions also quickly adapted to the new medium, using print to standardize liturgical practices and distribute approved devotional materials. This dual disruption and institutional adaptation pattern characterizes many media transitions.

Scientific collaboration was transformed as print created a system where knowledge could be shared, debated, and refined with unprecedented precision. The standardization of visual information—from anatomical drawings to astronomical observations—enabled more rigorous comparison of findings across distances. Scientific journals established new verification practices and citation norms that still underpin academic knowledge production. This print-based infrastructure for collaborative knowledge-building led directly to technological progress in numerous fields, from medicine to engineering (Shapin & Schaffer, 2011).

Political mobilization found new channels through print media. The rise of newspapers and pamphlets allowed for broader political participation, shaping revolutionary movements in Europe and America. Print created spaces for public opinion formation outside traditional power centers, gradually expanding the circle of people considered part of political discourse. These developments laid essential groundwork for democratic governance by making political arguments accessible beyond elites (Habermas, 1989).

Linguistic standardization emerged as an unexpected consequence of print technology. As printers sought to maximize their markets, they made spelling, grammar, and vocabulary decisions that gradually standardized vernacular languages. These standardization processes contributed significantly to national identities as linguistic communities consolidated around printed norms. Dictionaries and grammar books both documented and shaped these emerging standards, creating new forms of linguistic authority (Anderson, 1991).

Visual thinking underwent a profound transformation as the reproducibility of images changed how knowledge was organized and understood. Technical illustrations, maps, diagrams, and other visual formats became standardized through print, enabling new forms of communication that combined text and image in strategic ways. These developments led to new scientific and technical innovations by making complex spatial and structural information more precisely communicable (Tufte, 2001).

Information management systems developed for print continue to shape how we organize knowledge. Indexes, bibliographies, page numbers, and reference systems created for books established organizational principles that persist in digital environments. The codex format, bound pages between covers, established reading practices and informational hierarchies remain influential even as screens replace paper. These structural features of print culture are often so naturalized that we fail to recognize their historical contingency (Darnton, 1982).

Media literacy evolved in response to print technology, creating new cognitive skills and reading practices. Silent reading, previously uncommon, became the norm as printed books proliferated in private ownership. Critical thinking about textual authority developed as readers encountered conflicting printed sources. These cognitive adaptations to print culture evolved into modern approaches to information evaluation that we now apply to digital media (Mudaliar, Iyengar, & Ammal, 2016).

The printing press also demonstrates how technological revolutions create both disruption and opportunity. Economic displacement affected scribes and illuminators, who had to adapt to new roles or face obsolescence in a changing media environment. Some found positions in the emerging print economy, while others specialized in luxury manuscript production for elite clients. This occupational disruption and adaptation pattern continues in contemporary digital transitions (Hirsch, 1967).

Print technology transformed rather than eliminated knowledge gatekeeping. While democratizing information in some ways, print also created new forms of control through publishers, censors, and market forces. The economics of the press meant that not all voices had equal access to print platforms. These new gatekeeping mechanisms established patterns in modern media environments, where access to communication channels remains unequally distributed (Habermas, 1989).

Gutenberg’s legacy extends beyond specific technological innovations to encompass broader patterns of media development. The printing revolution demonstrates how technologies succeed through technical superiority and adaptation to social needs, economic systems, and cultural values. As we navigate our period of media transformation, this historical perspective offers valuable insights into how communication technologies reshape societies—gradually, unevenly, but profoundly—over time.

Canada’s Earliest Printers

The early history of printing in Canada offers an intriguing glimpse into the growth of communication in the young country, highlighting the role of printers in shaping Canadian society and culture. The beginnings of printing in Canada can be traced to the arrival of printers from Europe and the United States, who brought with them the revolutionary technology of the printing press. The earliest presses were established in the eastern provinces, slowly spreading across the country, and their influence extended into Western Canada as well, ultimately affecting Canada’s development in both profound and lasting ways (Scanlon, 2018).

It was not until 1751, almost 300 years post-Gutenberg, that the first press reached Canada. This long gap underscores how the technology spread slowly across the Atlantic and was adopted much later in Canada than in Europe. While Johann Gutenberg revolutionized printing in Europe in the 15th century, printing took nearly three centuries to establish itself in Canada, beginning in Halifax, Nova Scotia (Scanlon, 2018).

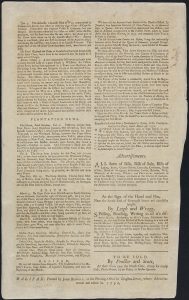

John Bushell, the first known printer in Canada, moved from Boston to Halifax, Nova Scotia, in 1751. Bushell was responsible for publishing The Halifax Gazette on March 23, 1752, the first newspaper in the country (Scanlon, 2018). As printing spread, it was introduced to other provinces in Canada, such as Quebec and New Brunswick, where presses were set up in 1764 and 1784, respectively (Scanlon, 2018).

Another key figure in Canada’s early printing history was William Brown, who, alongside his partner Thomas Gilmore, became the first printer in Quebec when they set up shop in Quebec City in 1764 (Scanlon, 2018). Brown’s medical pamphlet, published in 1785, is one of this era’s earliest surviving printed works (Scanlon, 2018).

John Ryan holds a special place in Newfoundland, having been the first printer in Newfoundland and New Brunswick (Scanlon, 2018). Ryan, alongside William Lewis, began their printing work in Saint John before moving to St. John’s in 1806 to establish the first press on the island. One of Ryan’s most notable early works is a proclamation issued in 1822, affirming the rights of French fishermen in Newfoundland (Scanlon, 2018).

As the country expanded westward, so too did the reach of the printing press. By the end of the 18th century, presses were established in Prince Edward Island and Ontario (Scanlon, 2018). Louis Roy became the first printer in Ontario when he set up a press in Newark (Niagara-on-the-Lake) in 1792 (Scanlon, 2018). These early presses were not just communication tools but foundational in fostering a sense of unity and identity in the emerging Canadian nation (Scanlon, 2018).

In the West and the North, the spread of printing was initially slow but began to gain momentum toward the end of the 19th century. The first presses in Manitoba and Alberta were introduced by missionaries, who used the technology to translate Christian religious texts into Indigenous languages (Scanlon, 2018). James Evans, a Methodist minister, established a press in Rossville, Manitoba in 1840, printing in Cree syllabics (Scanlon, 2018). Similarly, Émile Grouard, an Oblate priest, brought the first press to Alberta in 1876, producing the first book in the province, Histoire sainte en Montagnais (Scanlon, 2018).

The Fraser River Gold Rush of 1858 prompted the establishment of British Columbia’s first newspapers, including the influential The British Colonist, founded by Amor de Cosmos, who would later become the premier of British Columbia (Scanlon, 2018). Further north, during the Klondike Gold Rush, G.B. Swinehart produced the first printed material in the Yukon, publishing a single issue of the Caribou Sun in 1898 at Caribou Crossing (Scanlon, 2018).

From John Bushell in Halifax to G.B. Swinehart in the Yukon, Canada’s early printers laid the print culture’s foundation for the country’s growth (Scanlon, 2018). Their contributions included distributing information and creating a space for dialogue, identity, and exchanging ideas. The development of printing in Canada was a gradual but transformative process, as these early printers opened the door for the flourishing of Canada’s literary, political, and social life (Scanlon, 2018).

Summary

This chapter explored the printing press’s impact on human communication, tracing its evolution from oral traditions to print. It examined pre-Gutenberg printing technologies from Asia, Gutenberg’s specific innovations, the gradual popularization of print culture, and the printing press’s lasting legacy on society and concluded with the history of early printing in Canada.

Key Takeaways

Key takeaways from this chapter include:

- While Gutenberg refined printing in Europe, printing technologies existed centuries earlier in East Asia, with Chinese woodblock printing (7th-9th centuries) and Korean movable type (13th century) predating European developments.

- Gutenberg created a profitable system optimized for European alphabets through innovations in metal type, specialized ink, press adaptation, and novel business models.

- Print’s revolutionary impact unfolded slowly over generations as social, economic, and cultural factors aligned with technological change.

- Figures like Aldus Manutius, William Caxton, and Martin Luther expanded print’s reach beyond what Gutenberg achieved by adapting it to diverse social needs.

- Print revolutionized religion, science, politics, language standardization, visual communication, and information organization.

- Printing arrived in Canada in 1751 with John Bushell in Halifax, spreading gradually westward through the efforts of early printers who established foundations for Canadian print culture.

- The print revolution demonstrates how successful technologies require technical innovation and adaptation to societal needs, establishing patterns visible in today’s digital transitions.

Group Activity

Divide into groups (of 3 or 4) and discuss the following:

- Besides Bill Gates and Steve Jobs, what names do you associate with the invention of the computer?

- How are the names we remember regarding the history of technology decided upon (i.e., who makes these choices for us)?

- Should history be about (a) the inventors or (b) the technical details associated with the technology? Why?

Be prepared to summarize your group’s discussion and share it with the class.

End-of-Chapter Activity (News Scan)

Print Culture Impact

Purpose: This assignment helps you connect historical perspectives on print technology with contemporary developments, enhancing your ability to critically analyze how printing continues to shape information distribution and cultural communication.

Using Google News, find a recent article (published in the last three months) about printing technology, publishing industry changes, or print media’s role in Canada or globally.

In 250 words, respond to the following:

- Summarize the Article (100-150 words)

- Provide the title, author, and date in APA format.

- Explain the article’s primary focus and significance.

- Identify key findings or arguments presented.

- Connect to Chapter Themes (100-150 words)

- Relate the article to at least one key theme from this chapter (such as the impact of the print revolution, democratization of knowledge, or print vs. digital media).

- Analyze how the article illustrates continuity or change in print culture compared to historical patterns discussed in the chapter.

- Explain what the article suggests about the future trajectory of print media.

Cite your sources (textbook and article) in APA format.

References

Anderson, B. (1991). Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism (Rev. ed.). Verso.

Berne, D. (2024). The design of books: An explainer for authors, editors, agents, and other curious readers. University of Chicago Press.

Bigelow, C. (2018). Font wars note 31. In History of desktop publishing: Laying the foundation (Special issue). IEEE Computer Society. https://history.computer.org/annals/dtp/fw/fontwars-note31.pdf

Blake, N. F. (1991). William Caxton and English literary culture. A&C Black.

Briggs, A., & Burke, P. (2009). A social history of the media: From Gutenberg to the internet (3rd ed.). Polity Press.

Broomhall, S. (2018). Women and the book trade in sixteenth-century France. Routledge.

Brubaker, L., & Haldon, J. (2017). Byzantium in the Iconoclast Era (ca 680–850): the sources: an annotated survey. Routledge.

Chappell, P. (2011). Gutenberg’s press revisited: Invention and renaissance in the modern world. Agora, 46(2), 26–30.

Chartier, R. (2019). The cultural uses of print in early modern France. Princeton University Press.

Clanchy, M. T. (2012). From memory to written record: England 1066-1307. John Wiley & Sons.

Darnton, R. (1982). What is the history of books? Daedalus, 111(3), 65-83.

Davies, M. (1995). Aldus Manutius: Printer and publisher of Renaissance Venice. British Library.

De Hamel, C. (1992). Scribes and illuminators. University of Toronto Press.

Edwards Jr, M. U. (1994). Printing, Propaganda, and Martin Luther. Fortress Press.

Eisenstein, E. L. (1983). The printing revolution in early modern Europe. Cambridge University Press.

Febvre, L., & Martin, H. J. (1997). The coming of the book: the impact of printing 1450-1800 (Vol. 10). Verso.

Fisher, J. D. (2022). The enclosure of knowledge: Books, power and agrarian capitalism in Britain, 1660–1800. Cambridge University Press.

Füssel, S. (2020). Gutenberg and the impact of printing. Routledge.

Glover, D. (2012). Publishing, history, genre. The Cambridge companion to popular fiction, 15-32.

Habermas, J. (1989). The structural transformation of the public sphere: An inquiry into a category of bourgeois society (T. Burger, Trans.). MIT Press.

Hirsch, R. (1967). Printing, selling and reading, 1450–1550. Otto Harrassowitz.

Huang, S. S. (2011). Early Buddhist illustrated prints in Hangzhou. In Knowledge and text production in an age of print: China, 900-1400 (pp. 135–165). Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004192287.i-430.35

Ivins, W. M. (1969). Prints and visual communication. MIT Press.

Johns, A. (2000). The nature of the book: Print and knowledge in the making. University of Chicago Press.

Kim, J.-m. (2010, April 1). Jikji: An invaluable text of Buddhism. Korea Times. https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/common/printpreviews.asp?categoryCode=293&newsIdx=63447

Lehmann-Haupt, H. (1966). Gutenberg and the master of the playing cards. Yale University Press.

Lienhard, J. (1998, May 24). What people said about books in 1948.Mechanical Engineering Department, University of Houston. https://uh.edu/engines/indiana.htm

Maclean, I. (2012). Scholarship, commerce, religion: the learned book in the age of confessions, 1560–1630. Harvard University Press.

Man, J. (2009). The Gutenberg Revolution: How printing changed the course of history. Bantam Books.

Matheson, P. (1998). The rhetoric of the Reformation. T&T Clark.

Mudaliar, A. K., Iyengar, V. D., & Ammal, V. M. K. (2016). Readers, reading practices, modes of reading. The History of the Book in South Asia, 75.

Pettegree, A. (2014). The invention of news: How the world came to know about itself. Yale University Press.

Scanlon, M (2018, August 28).Canada’s earliest printers. Library and Archives Canada Blog. https://thediscoverblog.com/2018/08/28/canadas-earliest-printers/

Shapin, S., & Schaffer, S. (2011). Leviathan and the air-pump: Hobbes, Boyle, and the experimental life. Princeton University Press.

Shi, Y. (2010). The Diamond Sutra in Chinese Culture. Buddha’s Light Publishing.

The Morgan Library & Museum. (n.d.). The invention of printing. The Morgan Library & Museum. Retrieved March 6, 2025. https://www.themorgan.org/the-invention-of-printing.

Tufte, E. R. (2001). Visual explanations: Images and quantities, evidence and narrative: 2nd edition. Graphics Press.

Woods, M. B., & Woods, M. (2011). Ancient communication technology: From hieroglyphics to scrolls. Twenty-First Century Books.

Media Attributions

- Books before the press

- Black Computer Keyboard on Brown Wooden Table

- The common book

- Martin luther

- Gutenberg Bible

- halifax