2 Chapter 2: Pre-Literate Societies and the Role of Oral Traditions

Amanda Williams

Introduction

In an age dominated by information overload, it is easy to forget that there was a time when societies communicated primarily through oral means. Before the widespread use of written language, the world existed in a “pre-literate” state, referring to societies that did not have a writing system, where storytelling, symbols, and oral traditions were the primary methods of communication. This chapter explores the significance of oral cultures and visual communication in pre-literate societies, providing insight into the transition from orality to literacy and examining the enduring legacy of these traditions in modern communication.

The shift from oral to written communication is one of the most significant transformations in media history and key to the print revolution. While writing and print technologies introduced profound gains in knowledge preservation and intellectual development, they also led to the decline of communal, performative storytelling. This chapter offers a critical perspective on these changes and reflects on how the legacy of oral traditions shapes modern communication practices.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Describe how pre-literate societies preserved knowledge through storytelling, petroglyphs, and pictographs.

- Analyze Indigenous rock art’s role and ongoing significance in Canada and Alberta.

- Identify key gains and losses in the shift from oral to written communication.

- Recognize how oral traditions influence modern digital communication.

Oral Traditions and Pre-Literate Societies: A Critical Perspective

Studying pre-literate societies challenges long-held assumptions that cultures without written language were less sophisticated or complex. Societies that relied primarily on oral traditions demonstrated remarkable ingenuity in preserving and transmitting knowledge. Without written records, these communities developed intricate systems of storytelling, visual symbols, and memory aids to encode important cultural, historical, and practical information.

Oral cultures relied on skilled storytellers, known in different societies as griots (West African storytellers and musicians), bards, shamans, or Elders, to maintain and pass down knowledge across generations. These individuals were entrusted with histories, laws, spiritual teachings, and social customs, ensuring that collective memory remained intact. In many Indigenous communities, oral storytelling was a communal practice reinforced through ceremonies, songs, and visual representations. Unlike written records, which are fixed, oral traditions allow for adaptation and reinterpretation, making them dynamic and responsive to changing social and environmental conditions.

Visual Communication in Pre-Literate Societies

Before the development of written language, many societies used visual symbols to encode and transmit information. Petroglyphs (carvings on rock surfaces) and pictographs (paintings on stone, wood, or cave walls) were the earliest forms of recorded communication. These visual representations were not simply decorative but carried deep spiritual, historical, and territorial significance.

Many ancient structures and carvings reflect sophisticated knowledge systems that allowed pre-literate societies to track celestial movements, mark seasonal changes, and map migration routes. For example, monuments such as Stonehenge in England and the Easter Island statues (Moai) in the Pacific reveal the remarkable planning and ingenuity of societies that lacked written language (Desdemaines-Hugon, 2010). These enduring structures functioned as visual records, preserving sacred and historical knowledge in ways that written texts would later accomplish.

Even in the digital age, many Indigenous communities worldwide continue to uphold oral storytelling and visual communication as central elements of cultural preservation. In Canada, Indigenous nations such as the Blackfoot, Cree, and Métis maintain rich storytelling traditions, often in combination with visual forms like wampum belts, totem poles, and petroglyphs. Scholars emphasize that these traditions should not be viewed as primitive or outdated but as distinct and highly developed systems of knowledge transmission that continue to be relevant and resilient in the face of technological advancement (First Nations Studies Program, 2009).

Alberta as a Case Study: Petroglyphs and Pictographs

Alberta’s landscapes contain some of North America’s most significant rock art sites, revealing the sophisticated communication systems of pre-literate Indigenous societies. These sites, created by the Blackfoot (Niitsitapi), Stoney Nakoda, and Cree nations, are more than historical artifacts—they are living expressions of cultural identity that continue to hold deep meaning for Indigenous communities today. Their ongoing efforts to preserve and protect these sites testify to their commitment to their cultural heritage (Keyser & Whitley, 2006).

One of Alberta’s most significant rock art sites is Áísínai’pi (Writing-on-Stone Provincial Park), located in the Milk River Valley of southern Alberta. This site, designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site and a National Historic Site of Canada, contains one of the largest collections of Indigenous petroglyphs and pictographs in North America.

For thousands of years, the Blackfoot Confederacy has regarded Writing-on-Stone as sacred, using the sandstone rock faces to record important cultural narratives, spiritual experiences, and historical events (Brink, 2008). The petroglyphs at Writing-on-Stone depict:

- Hunting scenes, including bison hunts, that were central to Blackfoot survival and spiritual practice.

- Warfare and intertribal relationships, showing warriors on horseback, armed with bows and later guns, reflecting Indigenous engagement with European traders.

- Spiritual journeys and ceremonies, with figures representing supernatural beings and vision quest experiences.

- Celestial symbols, which some scholars believe relate to Indigenous knowledge of astronomy and seasonal cycles.

The rock art at Writing-on-Stone reflects a highly developed visual language understood and interpreted in combination with oral storytelling traditions. This interconnectedness of oral and visual communication in pre-literate societies is a testament to the complexity and richness of their cultural systems. Knowledge keepers and Elders ensured that each generation could understand the meanings behind these carvings, reinforcing cultural memory and identity.

According to Travel Alberta Canada (2025), beyond Writing-on-Stone, other rock art sites in Alberta reveal additional layers of Indigenous communication and historical documentation:

- Grotto Canyon (Canmore): A site featuring pictographs estimated to be 500–1,300 years old, believed to be associated with ceremonial practices and storytelling traditions.

- Grassi Lakes (Canmore): This site is home to well-preserved pictographs, including the Medicine Man figure. This figure depicts a human holding a sacred hoop, symbolizing Indigenous healing and spiritual guidance.

- Rat’s Nest Cave (Canmore): This cave contains 7,000-year-old pictographs and animal remains, believed to be linked to vision quests and sacred ceremonies.

- Okotoks Erratic (Foothills Region): This site features ancient carvings that map journeys across the prairies, reflecting the Blackfoot people’s deep connection to the land.

These sites face serious threats, including erosion, environmental damage, and vandalism. In recent decades, some pictographs have faded due to natural weathering, while others have been defaced by graffiti or tourist activity. In response, Indigenous organizations, archaeologists, and Alberta Parks have worked to protect and preserve these sites through legal protections, educational programs, and digital documentation projects.

For media history students, Alberta’s rock art sites offer a powerful lesson: communication is not just about technological advancement but human creativity, cultural memory, and the deep-seated need to share stories.

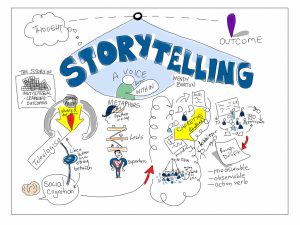

The Power of Storytelling and Symbols in Communication

Storytelling is one of humanity’s most fundamental ways of constructing meaning, preserving history, and fostering social cohesion. In oral societies, storytelling was not merely a form of entertainment but a method for transmitting knowledge, teaching values, and reinforcing community bonds (Ong, 1982). Storytelling was performed by skilled narrators, who ensured that the stories they told were accurate and consistent, maintaining the integrity of cultural memory.

Symbols, much like storytelling, serve as powerful vehicles for meaning. In pre-literate societies, symbols were embedded in oral traditions, reinforcing collective memory and serving as mnemonic devices. For example, Indigenous wampum belts in North America encoded treaties and agreements visually, which were then recited accurately in oral traditions (Battiste, 2013). This use of symbols in storytelling reflects how communication revolutions can build upon, rather than replace, earlier methods of knowledge transmission. From wampum belts to modern-day emojis, symbolic communication continues to evolve and play a critical role in sharing stories and ideas.

The Transition from Orality to Literacy: Gains and Losses

As Ong (1982) notes, the transition from oral to written communication transformed human cognition. Literacy enabled precise record-keeping and knowledge transmission across time and space but diminished communal knowledge sharing. While literacy improved the preservation, accuracy, and accessibility of information, it also reduced certain social interactions. The shift from orality to literacy brought significant benefits and notable losses, as summarized below.

| Category | Gains of Literacy & Print | Losses from Orality’s Decline |

| Knowledge Preservation | Information can be recorded, stored, and retrieved over long periods (Eisenstein, 1983). | Oral traditions relied on communal memory, which weakened over time as literacy spread (Ong, 1982). |

| Accuracy & Standardization | Writing and printing reduce transmission errors, ensuring greater precision of records (Eisenstein, 1983). | Oral storytelling allowed for adaptation and fluidity, which was lost with fixed texts (Battiste, 2013). |

| Dissemination of Ideas | Print technology enabled mass communication and widespread knowledge sharing (Eisenstein, 1983). | Orality fostered localized knowledge networks reinforcing cultural traditions (Ong, 1982). |

| Access to Education | Literacy expanded access to formal education and scientific inquiry (Bruner, 1991). | The shift to literacy marginalized non-literate groups, creating educational inequalities (First Nations Studies Program, 2009). |

| Social Interaction | Written communication enabled long-distance correspondence, expanding networks (Ong, 1982). | Oral cultures prioritized face-to-face interaction, reinforcing social bonds (Bruner, 1991). |

| Cultural Expression | Print allowed for new literary forms, such as novels and newspapers, shaping cultural identities (Eisenstein, 1983). | The decline of oral storytelling weakened communal and performative aspects of cultural transmission (Battiste, 2013). |

| Authority & Control | Written records enabled legal documentation, governance, and institutional organization (Eisenstein, 1983). | Power structures shifted, as those who controlled literacy gained influence over oral-based societies (Battiste, 2013). |

From Orality to Literacy to Digital Media: Continuities and Transformations

Understanding the transition from oral to written communication provides valuable insights into contemporary shifts in media, particularly the rise of digital media. Just as the shift from orality to literacy transformed how humans stored and shared information, digital technologies are now reshaping communication by blending elements of both traditions. Examining these historical transitions allows a deeper understanding of how media technologies evolve rather than entirely replace one another.

One of the defining characteristics of oral cultures was the communal and interactive nature of storytelling. Knowledge was transmitted through spoken narratives, reinforced through memory, and adapted to suit different audiences. The introduction of literacy brought new possibilities for preserving and standardizing information. However, it also made communication more individualized—reading became a solitary act, and written records created a permanent, unchanging version of events (Ong, 1982). The rise of print further reinforced this trend, allowing mass distribution of knowledge but often reducing the participatory nature of knowledge exchange (Eisenstein, 1983).

With digital media, however, aspects of orality have resurfaced. Social media, video content, podcasts, and live-streaming platforms encourage real-time, dynamic interactions like traditional oral storytelling. Users engage in continuous dialogue, remixing and adapting content like oral cultures once their stories are modified with each retelling. Unlike print, which fixes words onto a page, digital communication remains fluid; posts can be edited, conversations are ongoing, and meanings evolve through collective participation.

The shift to digital media also mirrors how oral traditions relied on symbols and visual storytelling. Emojis, GIFs, memes, and short-form videos are modern-day pictographs conveying emotions and complex ideas without relying solely on written text (Danesi, 2017). In many ways, digital media represents a hybrid form of communication, blending the permanence of literacy with the immediacy and adaptability of orality.

Furthermore, just as literacy once widened gaps in access to knowledge—privileging those who could read and write—digital media introduces new inequalities. Influenced by internet access, technological literacy, and platform control, the digital divide shapes who can fully participate in modern communication networks. Much like how the printing press revolutionized knowledge access and consolidated power among literate elites, digital technologies democratize information while raising concerns about surveillance, misinformation, and corporate influence (Zuboff, 2019).

By studying the transition from orality to literacy, it becomes clear that each significant shift in communication technology brings both opportunities and challenges. Digital media, rather than being an entirely new phenomenon, can be understood as an evolution that integrates elements of past communication revolutions. Recognizing these historical patterns provides a critical lens for analyzing contemporary media trends and their societal implications.

Summary

This chapter explores pre-literate societies’ reliance on oral traditions and visual communication. It examines Indigenous rock art sites in Alberta and analyzes the transition from orality to literacy. It discusses gains (improved knowledge preservation, accuracy, access) and losses (reduced communal storytelling, face-to-face interaction) in this shift, drawing parallels to modern digital communication.

Key Takeaways

Key takeaways from this chapter include:

- Pre-literate societies used oral traditions and visual symbols (petroglyphs and pictographs) to preserve cultural knowledge and maintain social cohesion.

- Storytelling was a vital means of communication for entertainment, teaching history, reinforcing social norms, and building community.

- Petroglyphs and pictographs were early forms of mass communication, sharing cultural narratives across generations.

- The shift from orality to literacy introduced positive and negative changes. Literacy expanded knowledge access but diminished storytelling’s communal and performative nature.

- The transition from orality to literacy provides a framework for understanding contemporary shifts in digital media, which blend elements of both traditions. Just as literacy changed how knowledge was recorded and shared, digital media reintroduces interactive, dynamic communication, raising new challenges and opportunities in knowledge access, participation, and control.

In studying the transition from oral to written communication, we see that each form carries unique strengths. Oral traditions’ vibrant, participatory nature reminds us that communication is fundamentally about human connection. As digital technologies now reintroduce elements of orality while preserving print’s permanence, we recognize that communication evolution often integrates rather than simply replaces what came before.

Group Activity

Exploring Communication Traditions

This activity encourages critical engagement with the strengths and limitations of oral and literate communication. Divide into six groups.

Teams A & B: Oral Culture Advocates – Argue for the strengths of oral traditions, emphasizing storytelling, community connections, and knowledge transmission. Prepare 4-5 speaking points.

Team C & D: Literacy Advancement Proponents – Defend the benefits of written communication, focusing on record-keeping, knowledge expansion, and the impact of print. Prepare 4-5 speaking points.

Group E and F: Neutral Observers – Analyze both perspectives, ask clarifying questions, and summarize key insights.

Discussion Questions

- How do different societies remember and transmit knowledge?

- What defines an effective communication method?

- How do oral and literate traditions continue to shape modern communication?

Reflection Prompts

- What communication skills from oral cultures remain relevant today?

- How do digital media blend oral and written traditions?

- Where does storytelling still hold power in contemporary society?

At the end of the discussion, Group C will summarize the key arguments and broader implications for understanding human communication. Prepare 4-5 speaking points.

End-of-Chapter Activity (News Scan)

Oral Cultures in Canada

Purpose: This assignment helps you connect historical perspectives on oral traditions with contemporary developments, enhancing your ability to critically analyze how oral cultures continue to shape Canadian society and preserve knowledge systems.

Using Google News, find a recent article (published in the last three months) about oral cultures in Canada, such as Indigenous storytelling, language revitalization, or oral histories.

In 250 words, respond to the following:

- Summarize the Article (100-150 words)

- Provide the title, author, and date in APA format.

- Explain the article’s primary focus and significance.

- Identify key findings or arguments presented.

- Connect to Chapter Themes (100-150 words)

- Relate the article to at least one key theme from this chapter (such as oral tradition’s role in preserving knowledge, the oral-written divide, or cultural transmission methods).

- Analyze how the article illustrates continuity or change in oral cultures compared to historical patterns discussed in the chapter.

- Explain what the article suggests about the future trajectory of oral traditions in Canada.

Cite your sources (textbook and article) in APA format.

References

Battiste, M. (2013). Decolonizing education: Nourishing the learning spirit. UBC Press.

Brink, J. W. (2008). Imagining Head-Smashed-In: Aboriginal buffalo hunting on the northern plains. Athabasca University Press.

Bruner, J. (1991). The narrative construction of reality. Critical Inquiry, 18(1), 1–21.

Danesi, M. (2017). The semiotics of emoji: The rise of visual language in the Internet age. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Darnton, R. (1982). What is the history of books? Daedalus, 111(3), 65-83.

Desdemaines-Hugon, C. (2010). Stepping-stones: A journey through the Ice Age caves of the Dordogne. Yale University Press.

Eisenstein, E. (1983). The printing revolution in early modern Europe. Cambridge University Press.

First Nations Studies Program. (2009). Indigenous foundations: Oral traditions and knowledge transmission. University of British Columbia.

Keyser, J. D., & Whitley, D. S. (2006). Sympathetic magic in western North American rock art. American Antiquity, 71(1), 3–26.

Musée de la civilisation (2025).Áísínai’pi. https://imagesdanslapierre.mcq.org/en/explore/aisinaipi/

Ong, W. J. (1982). Orality and literacy: The technologizing of the word. Methuen.

Travel Alberta Canada. (2025). Discover ancient art around Alberta. Travel Alberta. https://www.travelalberta.com/articles/discover-ancient-art-around-alberta

Zuboff, S. (2019). The age of surveillance capitalism: The fight for a human future at the new frontier of power. PublicAffairs

Media Attributions

- Petroglyph from Writing-on-Stone Provincial Park

- storytelling

- pexels-pixabay-267350