11 Chapter 11: Indigenous Peoples in Canadian Media

Kyle Napier

Introduction

This chapter highlights one side of the mediated coin: here, we look at media made about Indigenous Peoples in Canadian and non-Indigenous media — with an emphasis on media within Treaty 7. This overview provides a richer context as we review Indigenous Peoples’ own press in the next chapter. This chapter lightly applies common themes in media theory from scholars writing about Indigenous Peoples in the media. We will also review historical accounts and mediated representations of Indigenous Peoples from Columbus, settler-colonizers, and anthropologists, to more recent representations, such as a review of the influences of movements like the Oka Crisis, Idle No More, and land protection or protests in Canadian media.

Having an awareness of the intersecting histories of Indigenous Peoples, colonization, and media will give contemporary communicators the skills necessary to professionally and ethically represent, or work with, by, for and alongside Indigenous Peoples or other communities which are not one’s own. The histories of colonization are not unique to Canada; when media-makers apply a global and historical lens to their practice, they are better equipped to provide nuance and depth to their stories.

As you read this chapter, consider how the media addressed historical movements, as identified in the previous chapter. Consider also how your personal media practice will change. Collectively, the goal is for you to come away with a sharper perspective on media representations of the past, present, and future of Indigenous Peoples. The next chapter reviews the evolving nature of Indigenous Peoples’ sovereignty over their own media, media ethics, and intellectual properties involving Indigenous Peoples.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Identify colonial media frameworks like McCue’s “4Ds” and LaRocque’s “civ/sav” binary in Canadian newspaper coverage across historical periods.

- Trace Indigenous media representation from Columbus (1492) through contemporary movements, recognizing recurring stereotypes and themes that persist despite surface-level changes.

- Explain how the media has functioned as a tool of colonization using specific historical examples while evaluating contemporary efforts toward decolonized journalism practices.

Reading Media Theories and Themes

“An elder once told me the only way an Indian would make it on the news is if he or she were one of the 4Ds: drumming, dancing, drunk or dead” — Duncan McCue (2014, para. 1)

Where the last chapter considered many histories of Indigenous Peoples across this continent and beyond, this chapter finds media representations of Indigenous Peoples from non-Indigenous Peoples, from first accounts through key historical moments, to even a lack of news coverage in some areas.

Consider McCue’s (2014) W4D rule that he heard from an Elder: to make it in the media, you need to “be a warrior… beat your drum… start dancing… get drunk…, or be dead” (para. 5). Emma LaRocque, a Métis scholar from Big Bay, Alberta, also introduces the concept of a news media binarism, which she describes as “civ/sav” or that of the Canadian and the other; media contrasting the colonizing people as civilized, against the antithetical brutalistic and barbaric non-Canadians, the savages (LaRocque, 2010). As Clark (2014) writes, “For the mainstream media, Aboriginal communities are outside the public sphere until something bad happens” (p. 131).

Bonita Lawrence (2004) also introduces the term “extreme discursive warfare” to describe the complicity of media with the colonial interests of the nation-state. In 2004, the Canadian Association of Broadcasters self-reported their coverage of Indigenous Peoples as dramatically “under-represented,” and the representations of Indigenous Peoples were admittedly creating “stereotypical,” “negative and inaccurate,” and “unbalanced” representations (as cited in Clark, 2014, p. 107). Where Indigenous women are historically made “invisible” by exclusion from stories in the media, they become “hypervisible” in stories of deviance (Clark, 2014, p. 131). In print today, Indigenous Peoples are still reduced to tropic anachronisms of the “drunken, poor, drug addicted, violent and hostile” of the previous centuries of news before them (Mahtani et al., 2008, p. 124, as cited in Clark, 2014, p. 31).

This chapter also borrows heavily from the book Seeing Red: A History of Natives in Canadian Newspapers, authored by Anderson and Robertson (2011). Anderson and Robertson analyze the imagined binarism across themes such as cultural hegemonization, social Darwinism, tautological circularity, and exclusion of Indigenous narratives, addressed occasionally throughout this chapter. Consider how those themes have been consistent in media about Indigenous Peoples, and what you have heard to be the voice of public opinion in Alberta today. Consider the paradox of such media themes, as they coexist with Canada’s media themes of “transnational communication and migration, globalization, postcolonialism and convergence” (Clark, 2014, p. 17). As Clark (2014) identifies, these themes are not just in Canadian media but extensions of media representations of global Indigenous Peoples.

The First Writings About Indigenous Peoples in Europe (1492-1500s)

Of course, Canada wouldn’t be the Canada you know it as today without the involvement of Europe. In 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue, as the saying goes. In search of India, Columbus landed on Taíno and Arawak-occupied islands of the Caribbean. Among the voyaging trips, they had the four early tools of colonization from trade with China: guns, compasses, paper, and the printing press. Guns, as you can assume, created a power imbalance between the arriving colonizers and the Taíno and Arawak peoples. Columbus would nearly immediately act upon this power imbalance, wherein the ships which would join him on his voyages would entrap Indigenous Peoples, selling them into slavery.

Columbus’s first letter to his shipmates’ sister would set the precedent for the first writings about Indigenous Peoples of this continent. In the year 1500, he writes:

A hundred castellanoes are as easily obtained for a woman as for a farm, and it is very general and there are plenty of dealers who go about looking for girls; those from nine to ten are now in demand (Columbus, 1500, as cited in Thatcher, 1903, p. 348)

I would prefer to spare you the details about what exactly was written by Columbus and his crewmates regarding their treatment of the Taíno and Arawak women and children. Note, however, that they involved brutal details of sex and labour slavery and trafficking, while romanticizing the religious conversion of Indigenous Peoples through their languages. Such would set the precedent for colonial media, with harms lasting centuries.

In 1542, Bartolomé de las Casas, who had participated in colonial expeditions, published A Brief Account of the Destruction of the Indies (Brevísima Relación de la Destrucción de las Indias), which would likely be one of the first written accounts in opposition to the brutal treatment of the Indigenous Peoples of the so-called New World (Las Casas, 1542/1992).

Early Colonization and Catechisms; Early Publishers and Anthropologists (1600s — 1812)

The media produced between 1600 and 1812 would set the precedent for colonization. Literacy rates steadily increased throughout the 1600s, coinciding with the birth of printing in the Americas in 1639, when Stephen Daye brought a printing press with him and his two sons to Cambridge, Massachusetts. They would initially publish the Oath of a Freeman (1638), An Almanac for the Year of Our Lord (1639), and The Whole Booke of Psalmes (1640).

The Mamusse Wunneetupanatamwe Up-Biblum God, or as it was alternatively titled, the Eliot Bible, would challenge their printing monopoly. Published by John Eliot and Marmaduke Johnson in 1663, the Eliot Bible is primarily regarded as the first complete book and the first Bible ever published on this continent, and was printed entirely in the Wampanoag language. This publication is the earliest example of a catechism, in this case, a translation of a religious text into an Indigenous language.

As an academic field, anthropology began outside of the Americas, establishing its roots in Germany and expanding outward. In the Americas, anthropologists created the concept of race, which is understood today as racialization. Throughout the 1600s, Bernhard Varen would make the earliest classifications of people based on their racialization (Smedley, 1999). This was later followed by François Bernier, who published the “Nouvelle division de la terre par les différentes espèces ou races l’habitant”, or “New division of Earth by the different species or races that inhabited it in 1684.” These early anthropological racializing texts would contribute to assumptions of various global peoples’ physiological capacities, temperaments, and behaviours. In the late 1790s, Johann Friedrich Blumenbach published reports that compared skulls of global peoples, categorizing them as White, Yellow, Black, Brown, or Red. A few decades later, Samuel Morton would fill skulls of different groups of people with peppercorn and lead to measure the room in their skulls, later making racialized assumptions about brain capacity based on how many seeds, alternatively replaced with lead shot, could fit in their skulls. The results were used to justify slavery and assertions of white racial superiority and a racial hierarchy. The American Anthropological Association (1998) would later recant these racial categorizations in their “Statement on Race”, which determined race to be a social construct, rather than a biological or physical construct.

In Canada, Diamond Jenness, anthropologist and author of The Indians of Canada in 1932, described the long-standing history of Algonquians and Haudenosaunee as “petty strife between… two insignificant hordes of savages” (Jenness, 1932, p. 1, as cited by Younging, 2018, p. 35) as Younging (2018) writes, wherever the source, these early writings “provided little insight into the cultural realities of Indigenous Peoples. Yet this literature influenced the intellectual foundations of settler society in its perception of Indigenous Peoples as primitive and underdeveloped” (p. 36).

In 1690, John Locke would famously author his Second Treatise on Government, in which he would write, “because Amerindians merely roamed and foraged across the land, they did not own it” (Pagden, 1995, p. 46, as cited in Fee, 2015, p. 38). Locke would famously quote from the earlier Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan, wherein in 1651, Hobbes wrote, “there is no doubt … that aboriginal life in the territory was, at best ‘nasty, brutish and short’” (as cited in Culhane, 1998, p. 236, as cited in Fee, 2015, p. 39).

Indigenous Peoples had allied with the British throughout the Seven-Years’-War, between 1756-1763, the signing of the Royal Proclamation, up to the War of 1812. As a result, Indigenous Peoples were reflected favorably in EuroWestern print media through those periods (Fee, 2015, p. 63). Herein, Indigenous Peoples of the continent guided early democracy and inter-political diplomacy. Where the Peace and Friendship Treaties of the 1700s established an era of mutual understanding between Indigenous and non-Indigenous nations, and inspired America’s constitution, the relational tides between colonial governments and Indigenous Peoples would turn during the War of 1812. The British fought against the French; however, the French allied with the Indigenous Peoples of the area. Through allyship with Indigenous Peoples, French soldiers defended territories against the British. Britain then realized it needed to rethink their relationship with Indigenous Peoples.

Themes of Early News Media: Manifest Destiny, Cultural Hegemonization, and Racialization; From the Robinson Treaties to Treaties 1-7 (1812-1885)

“As for the future of this country, it is as inevitable as tomorrow’s sunrise.” —Toronto Globe, January 4, 1869

With the turn of the tide of the War of 1812, Britain would change how it perceived, treated, and dealt with Indigenous Peoples. While some Indigenous publishers across the continent began printing their newspapers in the early 1800s, most were faced with the exertion of colonial power. Here, the media has created what Daniel Francis refers to as the “imaginary Indian.” That is, the representation of Indigeneity that most people feel familiar with, though it is of a fictitious and generalized Indian, which does not exist.

Anderson and Robertson (2011) affirm what Bonita Lawrence describes as “extreme discursive warfare” (2004, p. 39) — media across Canada are, by design, complicit in maintaining colonial rhetoric bound to Canadiana. They address the media through the lenses of cultural hegemonization, embracing social Darwinism in print, and would continually describe Indigenous Peoples as culturally depraved and racially inferior. Common tropes of Indigenous Peoples included the “moribund Native, the savage, the Indian princess, the stoic or noble Native, the childish Native, the intemperate Native (a.k.a., the drunkard), and so on” ( p. 7).

One of the first books published in Canada, Wacousta written by John Richardson in 1832, would continue those themes: the author portrays a battle of the garrison and the wilderness between the civilized and the savages (Fee, 2015, p. 66). Richardson’s other novels continue this rhetoric of a savage, “demonic,” cannibalistic animal, representing the Native in literature. At the same time, colonizers “starved, killed, tortured, raped, and enslaved men, women, and children” (Fee, 2015, p. 93). These publications, coinciding with diverse populations of Indigenous Peoples, would see a fertile ground for the birth of early anthropologists.

The Globe and Mail would see its beginnings in 1844, initially published as The Globe. The Globe and The Gazette would quickly become Canada’s two most widely distributed newspapers. That same year, in 1844, the term “Manifest Destiny” would be coined by the Liberal party of the day in the United States, and then leveraged across the continent to justify colonization as God’s will (Anderson & Robertson, 2011). Ojibwe and Canada would sign the Robinson Treaties of the 1850s, the first attempt at land seizure via treaty. Inuit would begin being studied, beginning what Igor Krupnik (Julien Pongerard, 2018) describes as “Eskimology.” Canada would later adopt “manifest destiny” in both media and nationalistic rhetoric (Toronto Globe, December 29, 1869; Toronto Globe, March 8, 1869, as cited by Anderson & Robertson, 2011, p. 22). This God-sanctioned colonization would print ubiquitously in the early era of Canadian news media, following the precedent established by the since-repudiated Terra Nullius and Doctrines of Discovery, as addressed in the previous chapter.

By addressing the issue as one of religious and moral condemnation, newspaper media generalized or cast aside Indigenous Peoples’ many various religions and spiritual practices as heathens, if they were mentioned at all. Of course, Christianized Indigenous Peoples were regarded as those of better morals (Toronto Globe, July 7, 1873, as cited by Anderson & Robertson, 2011, p. 46).

Early newspapers placed the blame of starvation upon Indigenous Peoples, particularly of those they called the half-breeds. “The starvation here threatens 5,000 of the half-breeds, but only those. The farming classes are affected very little, if anything at all, by it. The half-breeds are a strange class. They will do anything but farm…” (Anderson & Robertson, 2011, p. 25). Invoking ungulacide, early papers recommended one way to “compel the Indians to settle down” by decimating the populations of bison on the plains (Toronto Globe, January 11, 1869 and Toronto Globe, January 27, 1869, as cited by Anderson & Robertson, 2011, p. 32). Action would follow, with the Star Phoenix reporting on the histories of Canadian soldiers and bison, writing: “American soldiers had killed off many of the buffalo across North America in hopes of wiping out the First Nations population” (July 7, 2005, as cited in Anderson & Robertson, 2011, p. 263).

The theme of racialized epithets grew beyond just publishing about Indigenous Peoples of the continent. These early publications, from 1869, frequently used racialized themes to denigrate the assumed moral integrity of those deemed to be non-White. Consistent with today’s newspapers, those who were not considered to be White were more likely to be identified by the reporter’s racialization of the subject.

Early writings in 1869 from The Globe and Gazette demonstrated unified themes in cultural hegemonization. Anderson and Robertson (2011) identify these themes as: “get the land [described as not belonging to Natives], minimize the threat posed by Aboriginals by dividing and conquering them via treaties and reservations, convert the heathens, tutor the children, root out wickedness and sin, and farm and otherwise exploit the resources in a way that God might endorse” (p. 33). Where newspapers would report on the gore of Indigenous Peoples who had killed “white men,” they would glorify the “expedition(s) against savages” (Toronto Globe, January 9, 1869, as cited by Anderson & Robertson, 2011, p. 31).

The following seven years (1870-1877) would begin the era of Canada’s numbered treaty-making. Per the Royal Proclamation of 1763, nations wishing to establish nationhood in the Americas needed to sign treaties with the respective countries. Canada would sign the first of its seven numbered treaties successively between 1870 and 1877. The following treaties, 8 through 11, would follow decades later during the rush for gold and the learning of oil, north of Treaty 6. “Aboriginals were compelled by force or the threat of the use of force. And that is precisely how the press portrayed it in the latter nineteenth century,” write Anderson and Robertson (2011, p. 4). Perhaps contradictorily, newspapers at the time would regard treaties as the solution to such an “Indian problem,” with The Gazette writing that treaties would “diminish the offensive strength of tribes, gratifies their attachment to their homes, gives them a market, and offer opportunities to the industries to attain a position of independence” (April 8, 1885, as cited by Anderson & Robertson, 2011, p. 76).

The Calgary Herald took a different position, declaring Indigenous people “thieves and murderers” (April 23, 1885, as cited by Anderson & Robertson, 2011, p. 77). Anderson & Robertson (2011) suggest this type of language could be thought of as genocidal, likely because such descriptors systematically dehumanized entire Indigenous communities and helped build public support for extreme government policies against Aboriginal peoples.

Similar to contemporary news accounts, Indigenous Peoples are often painted by media with the brush of extinction, as a people, with languages and cultures, that will one day die out. Indigenous Peoples were then, and are now, also frequently cast into one mould, as if the Nakota, Siksika, nêhiyawak, Dene, Métis groups, and Inuit are not their distinct peoples and nations. Instead, Indigenous Peoples were often written and described under the unified “Indian problem,” as would be the rhetoric of newspapers, and eventual verbiage attributed to Duncan Campbell Scott (Anderson & Robertson, 2011, p. 42). What were then referred to as half-breeds, and today referred to as Métis, faced their own social hierarchies; French-Métis, which made up the majority of Métis, were viewed as less than their Scottish- or English-Métis counterparts, particularly following the French-Métis support of the Louis Riel Rebellion.

Contemporary Media and Communications About Indigenous Peoples of Treaty 7

Before we even get to the media from Indigenous Peoples, we have to understand the context of the Indigenous Peoples of the lands respective to where you are. If you are reading this as a student at Mount Royal University, you are likely well aware that you are on Treaty 7 territory by now. You should know that this land has only recently been referred to as Treaty 7.

This treaty is binding between the Crown and the Indigenous Peoples of Treaty 7. Treaty 7 was signed in 1877, a decade after the formation of Canada. Treaty 7 is a contract bound in signatures and ceremonial pipe smoke, conducted between the Crown (or the royalty of England, as represented by Canada), and the Niitsitapi (Blackfoot Confederacy), which includes the Siksika, Piikani, and Kainai, as well as the other Indigenous nations to Treaty 7, which include the Îyârhe Nakoda (Stoney), and Tsúùtʾínà.

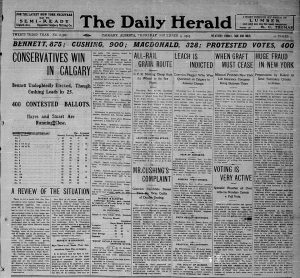

The Calgary Herald began its publication in 1883, one year before Calgary was incorporated as the first town in Alberta, in 1884. The Calgary Herald reports that the first freight train arrival on August 31, 1883, in Calgary would also bring the first hand-operated newspaper printing machine, bringing The Calgary Herald to life.

The Calgary Herald would also report on Indigenous Peoples outside of Calgary and Treaty 7. Reporting on the first Indigenous woman to pursue a law degree in 1905, The Calgary Herald would publish, “She wants to learn law so that she may go from tribe to tribe teaching her pathetic people their rights under the white man’s law” (January 13, 1905, as cited in Anderson & Robertson, 2011, p. 248).

A June 1969 Calgary Herald report described a travelling pow wow group as “Indian warriors in feather head dresses and buckskins,” who had “invaded” Paris, France — in the same issue, referring to then 1968 reigning and touring national Indian princess, Vivien Ayoungman, as a “beauty queen” (Calgary Herald, June 30, 1969, as cited in Anderson & Robertson, 2011, p. 195). The Indian Princess assuaged the colonial imaginary by being non-threatening and affirming the dominance of a Western hierarchy through the imaginings of British royalty. Outside of descriptions of “shapely” if not starved Indigenous women, were stories of abuse, violence, and promiscuity, with media referring to women in terms that I dare not print as a professional in the print medium.

Fast forward 20 years to the heyday of the cassette tape. Have you heard of Brocket 99? Recordings were released on cassette in 1986, with a tagline, Rockin’ the Reservation. The series was premised to have taken place on the Peigan Nation and hosted by Ernie Scar. This would be one radio example of pretendianism, looked at more closely in the next chapter. Regardless, the content was viewed as racist, offensive, and frankly, bad radio—that said, the tape was an international phenomenon. Tim Hitchner, a non-Indigenous radio host out of Lethbridge, was the voice of Brocket 99. He passed away in 2011.

Reporting on the Louis Riel Rebellion (1885)

Early newspapers were more than complicit in establishing public hierarchies of racialized peoples. Where global Indigenous Peoples were also racialized and categorized, with Indigenous Hawaiians and Maori tending towards the top of the Indigenous hierarchy, French Half-Breeds often were at the bottom of the rung of the social ladder. As The Calgary Herald would publish, “the Metis mind is exaggeratedly simple” (March 5, 1885; also see Calgary Herald, May 7, 1885, as cited in Anderson & Robertson, 2011, p. 73). This coverage would contribute to the Canadian public’s opinion of the Louis Riel Rebellion. Where today, Indigenous Peoples are often regarded as such, or preferably by their nationhood, in 1885, more common terms in the newspaper lexicon were “savage,” “heathen,” “pagan,” “redskin,” “redman,” “children of the plains/forest,” “semi-savages,” or perhaps most respectfully at the time, “Indian” (Anderson & Robertson, 2011, p. 68). Embellished news accounts would publish accounts from their presumed imaginary of barbarism, describing brutalities which had never taken place (Anderson & Robertson, 2011, p. 72), and hardly recanting their position. The Riel Rebellion would also be addressed with many monikers, including “Riel Insurrection,” “the Riel Trouble,” “the Riel Rumpus,” “the North-West Riot,” “Riel Troubles,” or “the North-West Difficulty” (Anderson & Robertson, 2011, p. 69). Owed to the patriarchy, Indigenous women were placed even lower, and referred to in the media often within the binarism of an Indian Princess, or as the derogatory term “squaw”, an English neologism derived from several derivations from Indigenous languages.

While racialization ran hot off the press, so did the patriarchy. Where a majority of Indigenous societies may have been matriarchal, contemporary Canadian-hood, and the Indian Act, insisted on patriarchal governance and publications. This legislation would further exclude Indigenous and other racialized women from contributing to meaningful societal changes, until 100 years later, following the Suffragettes and various waves of feminism. The early patriarchy would paint over the ancestral matriarchies of Indigenous societies, reducing Indigenous women and women-led governance to colonial gender archetypes within Indian Act governance models.

During this same period, the North-West Mounted Police would be formed, with initial tasks of controlling Indigenous populations, quelling the Red River Rebellion, and removing Indigenous Peoples from the two newly formed national parks — both Banff National Park and Wood Buffalo National Park.

In 1885, Louis Riel would be hanged on an obscure charge from a British statute from 1351, by which Riel was charged with high treason for “being moved and seduced by the devil” and “most wickedly, maliciously and traitorously” having levied and made war “against our Lady the Queen” (Fee, 2015, p. 115). Where Riel’s defense of Indigenous lands paralleled that of Indigenous Peoples, and the mixed Indigenous-European Mestizos across the newly formed nation-state of Mexico, the public hanging of Louis Riel would send a message to those exercising Indigenous sovereignty — Indigenous rebellion will be seen as barbarism against the backdrop of Canadian, American, and Mexican colonization. The area where Louis Riel was hanged stands today as a training and heritage centre for the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

While this would be widely reported in The Gazette, The Globe, and further out West, The Calgary Herald holds contradictory positions. At the time, more liberal newspapers, including The Calgary Herald, foisted the blame of Métis-Canadian tensions squarely on the reigning John A. Macdonald government. In contrast, others, more conservative distributions, such as The Examiner and The Citizen, attributed the blame to Riel. As stated in the Ottawa Citizen (May 18, 1885): “If law and order are to be maintained in Canada; if authority is to be respected…Riel must pay” (as cited in Anderson & Robertson, 2011, p. 64). Despite their earlier positions, consensus among the newspaper distribution, including The Calgary Herald, was that Riel should be hanged for treason (Calgary Herald, December 2, 1885, as cited in Anderson & Robertson, 2011, p. 65).

Treaties 8-11; Residential Schools; Gold, Oil, Diamonds, and Fending Off the Americans (1885-1921)

What would follow was an era of treaty-making north of Treaty 6. The discovery of gold, oil, and diamonds across lands North of previously treatied areas, including what’s now referred to as Fort McMurray, the Yukon, and the Northwest Territories, would be subject to further colonial encroachment. Treaty 8 would be signed in 1899, with later adhesions, kick-starting further treaty-making across the North. This event would coincide with the Yukon Gold Rush and early gold and diamond mining. The early trope of the Cowboys and Indians binary, exemplified in the era of the Yukon Gold Rush and American Indigenous genocide, would be reflected in early films representing Indigenous Peoples, such as Shane (1953) and Dances With Wolves (1990).

Anderson and Robertson (2011) identify five main themes across media of this era: the seizure of land for resources; the Cowboys and Indians trope; the epoch of a “frontier civilization”; Indigenous Peoples existence as inviting colonialism; and, lastly, the myth of colonization as evolution (pp. 84-85). The verbiage used to describe Indigenous Peoples of this era was still that of savagery. Here, newspapers maintained the positions of Canadian public opinion, “savage Indians” necessitated colonial violence, and simultaneously interrupted Canadian expansionism. Between 1876 and 1890, the period saw the fabrication of accounts in news stories across American news media. The first Battle of Wounded Knee would see glorified accounts of colonial war (1890).

This era also marked the stark growth of Canada’s residential schools. As addressed in the previous chapter, Canada’s history of residential schools drew its inspiration from America’s flagship militarized boarding school in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. Early missions on the continent began in the 1500s. The first industrial boarding school to attempt to convert Indigenous Peoples into Christianity opened in 1828. The next few decades would see various attempts by Canada’s nation-state to establish boarding schools as a means of converting Indigenous Peoples.

Nicholas Flood Davin and Duncan Campbell Scott are addressed in the previous chapter. Davin was the chief author of the Report on Industrial Schools and Half-breeds, or the Davin Report (1879). This report affirmed to the state the practice of removing Indigenous children from their homes to place them into residential schools. While residential schools had been trialled in Canada since 1828, Canada began partnering with various church denominations to deliver state-sponsored residential schools in 1883. Residential Schools became mandatory the following year through the Indian Act in 1894.

Both Davin and Scott wrote poetry glorifying assimilation. Consider the poetry of Duncan Campbell Scott, in “Onandaga Madonna” (1898), representing the political will of the era:

The Onondaga Madonna – Duncan Campbell Scott

She stands full-throated and with careless pose, This woman of a weird and waning race, The tragic savage lurking in her face, Where all her pagan passion burns and glows; Her blood is mingled with her ancient foes, And thrills with war and wildness in her veins; Her rebel lips are dabbled with the stains Of feuds and forays and her father’s woes. And closer is the shawl about her breast, The latest promise of her nation’s doom, Paler than she her baby clings and lies, The primal warrior gleaming from his eyes; He sulks, and burdened with his infant gloom, He draws his heavy brows and will not rest.

What would follow would initiate decades of some of the worst atrocities committed against Indigenous Peoples in Canada. In Calgary, a Cree sex worker was murdered in 1889, referred to as “only a squaw and that her death did not matter much” (Carter, 1997, p. 189). The man charged with manslaughter was given a lighter sentence, with The Calgary Herald concluding, “Keep the Indians out of town” (March 6, 1889, as cited in Anderson & Robertson, 2011, p. 201). The National Inquiry on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls will be reviewed later in this chapter.

Nearly thirty years after residential schools became mandatory, Dr. Henderson Bryce published what would become known as the Bryce Report, or The Story of a National Crime, which was an Appeal for Justice to the Indians of Canada (1922). This would be the first public report addressing the stark and unjust inequities, including experiments of nutrition deprivation against Indigenous children, as carried out by the residential schools project (Morrisseau, 2022).

Media Coverage of Indigenous Peoples in World War I and World War II (1914-1951)

The decades aligning with both World War I and World War II would see Indigenous participation in global wars, with Indigenous languages ironically weaponized against the backdrop of global imperialism on the other side of the world, while banned in residential schools. Where Canada and the United States condemned globally apparent genocides, and the holocaust, these North American nation-states simultaneously subjugated and dispossessed Indigenous Peoples by similar means. The League of Nations was formed in 1920, though, as addressed in the previous chapter, Indigenous Peoples remain neither invited nor allowed to voice the concerns of their nations and societies with the same treatment as colonial nation-states.

While the “militant” trope had long been established, the “Indians-at-war” trope began by 1941, emerging in cadence with Indigenous soldiers enlisted as uncrackable Code Talkers. On this continent, Indigenous collective rights groups would begin forming in the 1940s, such as the Northern Indian Brotherhood in 1945 and the Union of Saskatchewan Indians in 1946.

A turning point for Canadian perception of Indigenous Peoples was after the Second World War. Following World War II, Canada would be subject to global scrutiny for the treatment of Indigenous Peoples on the lands it was actively colonizing. Campaigns led by veterans groups and church organizations in the late 1940s would lead to the formation of a Special Joint Committee of the Senate and House of Commons in 1946. This SJC would contribute to alleviating some but certainly not all of the more egregious limitations upheld by the Indian Act, some of which were rescinded in 1951 (Anderson & Robertson, 2011, p. 138).

Indigenous Peoples would be faced with forced relocation, exceedingly so throughout the 1940s. Such forced relocation, or municipalization, relied on false promises to Indigenous Peoples, but had also removed impacted Indigenous Peoples from their ancestral harvesting practices. This disjunction would contribute to the media’s reification of Canada’s paternalistic fiduciary commitments to Indigenous Peoples, establishing a myth of “laziness” which had been omnipresent in the earliest of newspaper depictions of Indigenous Peoples.

The late 1940s would again see this nation-state paternalism fixated upon the Inuit, the Indigenous Peoples of the Arctic. Starting in 1944, Inuit women would be given state-sponsored “family allowance funds,” available at their nearest Hudson Bay Company outlet. They would receive provisional programming designed to steadily assimilate Inuit into the Canadian imaginary. Shortly thereafter, through the ’50s and ’60s, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police would begin deliberate killings against Inuit sled dogs. Where Inuit requested a commission for public record on the matter, the RCMP determined themselves not to be at fault (Edmonton Journal, July 2, 2005, as cited by Anderson & Robertson, 2011, p. 261).

More favourable coverage of Indigenous Peoples, though still stereotypically and racially-charged tropic publication, would fade again by the end of the war in 1948 (Anderson & Robertson, 2011). Themes of violence, alcoholism, poverty, and promiscuity continued to pollute the narrative of Indigenous Peoples; hereby, those with publishing power had usurped the narrative sovereignty of Indigenous Peoples.

A Self-Conscious Nation: Post-World War II, the White Paper, and Wounded Knee (1951-1982)

Returning from war, Treaty Indian veterans were not granted the same veteran benefits as their full-Canadian peers. News media depictions of Indigenous Peoples would revert to their classic vitriol with which they had grown comfortable. Cultural movements like the Calgary Stampede “provided opportunities to position Aboriginal peoples as spectacle on slow news day” (Anderson & Robertson, 2011, p. 142), while news productions denigrated, “mocked and satirized the Native Other.” While in 1960, those determined to be First Nations Indians were granted the right to vote in federal elections, the Hawthorne Report of 1966 identified Indigenous Peoples famously as “Citizens Plus” or as if they were Canadians with additional rights. This moniker would not consider that treaty and status Indians were restricted to reservation economic apartheid, subjected to broken treaty promises, the ungulacide and environmental degradation of environmental colonialism, and who were currently in the throes of Canada’s horrific residential school experiments.

The American Indian Movement, a broader intercontinental Indigenous rights group akin to the Black Panthers, was formed in 1968. In 1969, 89 prominent Indigenous rights activists occupied Alcatraz Prison, a prison located on an island off of San Francisco Bay. They protested federal ownership of the island, of which the state disavowed commitments made in the Treaty of Fort Laramie. This resulted in direct international media attention to Indigenous Peoples’ rights and treaty commitments.

Tensions ran amok. North of the U.S. border, in 1969, the Pierre Trudeau government would attempt to pass what had been colloquially deemed the White Paper, a legislative attempt at reducing Indigenous Peoples to Canadians, and disavowing commitments made through treaties and otherwise. This attempt would propagate the media themes of social Darwinism — that of a more powerful dominator who has undoubtedly won in its oppression of other peoples. Media themes harken back to the initial era of assimilation emerging a century prior (Anderson & Robertson, 2011, p. 157). The White Paper would have also offloaded federal responsibilities to the provinces. And so, then-Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau was faced with resistance from both Indigenous Peoples and the provincial leaders of his own country. Even Indigenous gatherings to address this legislative encroachment were critiqued by the media as themselves based on “white radical thinking,” per the Edmonton Journal (July 4, 1969, as cited by Anderson & Robertson, 2011, p. 165). Leaders and delegates of 42 Indian bands across Alberta began creating policy responses to the proposed White Paper.

Larger Indigenous rights collectives began taking hold. The National Indian Brotherhood would form to organize resistance movements across so-called Canada, at the time led by Walter Dieter from 1968 and George Manuel from 1970 to 1976. The Indian Brotherhood of the Northwest Territories was formed in 1969. Two prominent Indigenous women’s rights groups would form, including the Indian Rights for Indian Women in 1970, and the Native Women’s Association of Canada in 1974. The Rotisken’rakéhte, or the Mohawk Warrior Society, was formed in 1973, representing the Kanien’kehá:ka, or Mohawk people. An Ojibwe Warrior Society would form around the same time.

In the summer of 1970, 150 distinct Indigenous leaders across Alberta convened on Parliament Hill, presenting the newly formed “Red Paper” (a response to the White Paper) to the federal government. The Red Paper, penned by Harold Cardinal, leaned into the Citizens Plus moniker previously introduced in the Hawthorne Report. Eventually the prime minister took action to remove the White Paper, wherein even The Calgary Herald recognized that Trudeau saw the withdrawal as “inevitable” (June 8, 1970, as cited by Anderson & Robertson, 2011, p. 167).

News at the time continued to paint a binary, from barbarism to inevitable assimilation, even so far as quoting Indigenous Peoples in the media who favoured the English language and assimilation, without seeking counter-opinions from other Indigenous community members. Patterns of cultural hegemony, social Darwinism, and the contradictory rhetoric of “stubborn” and “lazy” “children” to the “violent” “militant” “savage” would persist, drawing its influences from the earliest newspapers a century before. However, the press would predict that escalating tensions would lead to an escalated response by Indigenous Peoples across Canada. These media tropes were not just limited to Canada, however. At the same time, Syed Alatas, a Malaysian decolonial scholar, would identify the hashing of laziness as a trope to describe Indigenous Asian Peoples across the Pacific Ocean, shedding light on this delineation as a globally reductive phenomenon.

While media coverage of the second Battle of Wounded Knee (1973) and the shoot-outs at Pine Ridge Reservation (1976) fanned the flames of international vitriol towards Indigenous Peoples in the United States, Canada faced its own equivalents in both Kahnawake (1973) and the Bended Elbow, Kenora (1974), at the Anicinabe Park Standoff. An issue of the New York Times (August 19, 1974) stated, “The Ojibway say the park was Indian land sold illegally to the city of Kenora by the Department of Indian Affairs in 1959. The militants also demand social reforms for some 7,000 Indians, most of them impoverished, in Kenora and nearby reserves.”

Consider this letter, written by Judy Parkes, in response to the Ojibwe Warrior Societies’ response to the protest (Letter to the editor, Kenora Miner and News, July 2, 1974, as cited in Anderson & Robertson, 2011, p. 182):

If you want equality, seriously, then cut your ties with the government and their juicy grants and free houses; step out into reality from your dream world, pick up your load…You’re so selfish…Can you name one group of people of any race, creed or colour in all of Canada who are given free education, free houses, free land, free medical, free dentistry and also don’t have to pay income tax or any sales tax? And what’s more, they don’t even appreciate it! Admittedly, Indians have a problem, a drinking problem. One of these could be remedied if their hands were kept busy at work.

Do any of those statements sound familiar? Have you heard similar rhetoric today? What lived realities, such as economic apartheid, forced removal from lands, and residential schools, might contradict that? Consider where “the mainstream press (has been viewed) as a central instrument in structuring and naturalizing colonialism”? Does this play true in contemporary social media?

National newspaper coverage would revert to its previous publishing patterns: the same themes apparent in coverage in the late 1800s, to post World War II, would remain apparent in a post-Red Paper Canada. That is, Indigenous Peoples were generalized and cast together without distinction whether as First Nations, Inuit, or Métis individuals, or of their own professional or relational affiliations, or regarding their own ancestral heritages; another brush consistently painted Indigenous Peoples as drunks; a third brush painted Indigenous Peoples as stoic against the ongoing face of colonialism; another brush, in classic North Americanist propagation, would criticize the “communal existence” and collectivism of various groups of Indigenous Peoples, contrasted against the rugged entrepreneurial and industrial individualism; and lastly, the brush of eventual extinguishment remained a constant angle of Canadian news media, casting Indigenous Peoples as “vanishing Indians” with an eventual extinction (Anderson & Robertson, 2011). Where news covered similar crimes, news media would report on the barbarism of Indigenous crime in richer detail than when reporting on the same crimes committed by non-Indigenous criminals. Where the media is painted with the brush of public opinion, public opinion would effectively reflect the media’s portrayal, and the impacts on the painted portrait of public opinion persist to this day.

Canada would change its previous national legislation, the Canadian Bill of Rights of 1960, into the Canadian Charter of Human Rights and the Canadian Constitution in 1982. Indigenous Rights would then be reaffirmed through section 35 of Canada’s constitution, though similar human rights provisions in section 25 are often awarded less media attention.

The same year, the National Indian Brotherhood would dissolve, responding to criticisms that it did not represent the needs of all Status Indians, and that year was reinvented as the Assembly of First Nations.

Media Shift: Oka Crisis, RCAP, Stephen Harper’s Apology, Idle No More, UNDRIP, and the TRC (1990-2015)

The Oka Crisis of 1990 would bring national attention to the complex role of colonization against Indigenous Peoples. The municipality of Oka, Québec, had sought a golf course across a bridge. The lands they had deemed to be appropriated for a golf course were located on the ancestral burial grounds of the Kanyen’kehà:ka. To this day, mainstream media has framed this as the Oka Crisis. While Oka is the community that wanted a golf course, it is not exactly a crisis to go without. However, for the Kanyen’kehà:ka, or Mohawk, of Kanesatake, this was about protecting their ancestral burial ground from development.

This 78-day stand-off would receive national media attention, in newsprint and on television. To the Kanyen’kehà:ka, as their land had never been ceded, there was no right to grant a golf course on those lands. Two thousand five hundred members of Canada’s armed forces were turned against the Kanyen’kehà:ka. Where then-Prime Minister Brian Mulroney referred to the Kanyen’kehà:ka as “terrorists”, the media lens was instead on Canada’s enforcement (McArthur et al., 1999, p. 417). Commonly, mainstream media would reproduce statements from Canada or its military media branches, but not give the same print space to the voices of the Kanyen’kehà:ka. As Anderson and Robertson are both university instructors, they identify that with each passing class, increasingly fewer university students are familiar with the extent of the Oka Crisis and its role in Canadian national identities.

The Oka Crisis initiated the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP), 1991-1996, a larger inquiry into the relationship between Indigenous Peoples and Canada. The commission concluded with extensive recommendations for reconciliation and renewed relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in Canada.

In 1997, the last residential school in Canada closed. News coverage of residential schools would frequently cover the abuses maintained by priests and nuns of the schools. Still, it would bring little attention to the larger systemic impacts of cultural and linguistic hegemonization. At long last, then-Prime Minister Stephen Harper publicly apologized for residential schools in 2008. The next year, he would famously mis-state at the G20 that Canada has no history of colonialism.

The United Nations passed the Declaration of Rights for Indigenous Peoples, or UNDRIP, in 2007. Of 193 member states of the United Nations, only four expressed dissent. Can you recall which nations? They are Canada, the United States, Australia, and New Zealand, each nation which would have plenty to atone for their treatment of Indigenous Peoples. While Canada originally dissented against UNDRIP, it would pass a law later to harmonize UNDRIP with Canada’s laws. This does not mean that UNDRIP has been passed in full at the federal level in Canada.

Following their thorough analysis of the implicit colonial biases of early news media to 2011, Anderson and Robertson (2011) write, “what we discovered through a discourse analysis of Canadian newspapers is that little has changed” (p. 16). As they write, “colonial stereotypes have endured in the press” from Canada’s earliest colonial imaginaries to today (Anderson & Robertson, 2011, p. 268), and exist in what the authors describe as tautological circularity, the hashing of new terminology and words with the same implications. The tropes of yesteryear have a new face: where the terms “savage,” “pagan,” and “squaw” are less likely to occur in contemporary newspaper reporting, the words have been replaced with the more tolerant “warrior,” or even a reduction to “sex worker.” Indigenous Peoples knowledge and stories are reduced to “myths” and “folklore” while textualized colonial religious texts dominate as doctrine and scripture, justifying manifest destiny. Sometimes, contemporary authors will describe behaviours while excluding others, emphasizing the role of an Indigenous woman murder victim as a “sex worker,” rather than a mother of two, or her relational connections to home. Where columnists of the past rehashed tired rhetoric, the same vitriol can be found across social media.

However, those tired tones and tropes would change dramatically in the media with the turn of Idle No More and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission recommendations. As the only Indigenous journalism student in the communications wing at Mount Royal University in 2012, I naturally covered the Idle No More rallies for MRU’s Calgary Journal. The shift in media attention and tone to Indigenous Peoples was palpable and undeniable.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission launched in 2008, following the mandate of RCAP, and Canada’s largest class action lawsuit: the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement. Nearly 7,000 residential school survivors gave testimonies, informing the TRC’s final report (Vowel, 2016, p. 171). In one hearing, the RCMP delivered a 500-page testimony explaining their role as residential school enforcers. In their own words, mounties “transported” children, and were active in “returning runaway children” (Clark, 2014, p. 128) consider the choice verbiage of the RCMP, rather than the words “stole,” “abducted,” or their commitments to “cultural genocide” as would later be used in the TRC.

In 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission released thousands of pages of research addressing the harms of residential schools. It provided succinct recommendations through the 94 Calls to Action (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015).

#MMIWG and #REDress: Addressing Systemic Gendered Discrimination in Media

[Note to reader: this particularly section addresses especially traumatic content, related to sexual violence and rape. Read this section with awareness and caution.]

Since Columbus’ first letters to his shipmates’ sister, Indigenous women have been written and described in words which are traumatizing to read, but in ways which would explicitly endorse the sexual slavery of Indigenous women across the continent, reduced as subjects to the colonial patriarchy in both print and conduct.

Since the imposition of the Indian Act in 1876, First Nations women with Status as a Treaty Indian would lose their status if they married a non-Indigenous man. At the hands of the provisional patriarchy in the Indian Act, 25,000 Indian women lost their status instantly (Holmes, 1987, p. 14, as cited in Anderson & Robertson, 2011, p. 206). However, at the same time, non-Indigenous women gained Treaty Status by marrying a man with Treaty Indian Status. As this was negotiated in Canadian courts, the two women spearheading the legal action against these sexist provisions then became targets of the media: “traitors,” and were targeted by various Indigenous governments.

This would call into question a legal matter which stands to this day: to what extent are Indigenous nations, with their own self-government proceedings, held to Canada’s Bill of Rights, or more contemporarily, Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms? In a significant supreme court ruling, it was determined that Canada’s Bill of Rights does not apply to Indigenous women, and with minimal respective media coverage. As the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms passed in 1985, Anderson and Robertson (2011) observe: “while photographs in papers throughout the nation showed feminists toasting to the success of the passage of the Charter, Aboriginal women were decidedly absent in press images of this celebration” (St. John’s Evening Telegram, April 17, 1985; Winnipeg Free Press, April 18, 1985; Toronto Star, April 18, 1985, as cited by Anderson & Robertson, 2011, p. 212).

The Calgary Herald even described the situation as “catastrophic” for Tsuut’ina Nation, then referred to as Sarcee Nation (itself an offensive term), as there would be a lack of funding to manage the influx of band members with rightful heritage and connection as Tsúùtʾínà (“Indian Act Amendment ‘Catastrophic,’ Warns Band,” Calgary Herald, June 30, 1985, as cited by Anderson & Robertson, 2011, p. 214).

It got even more complicated after 1985 with the introduction of Bill C-31. Now consider how Canada measures one’s status as a Treaty Indian by blood quantum, and Canada is the one who authorizes one’s Status as a Treaty Indian. If Canada determines an individual is a full status, they are deemed 6(1). If a 6(1) Indigenous person has a child with a non-Status person, then that child becomes 6(2). If a 6(2) Status Indian has a child with a non-status person, then their child would be deemed non-status. While non-status Indians can hold band membership, they do not receive the benefits of having Indian Status. As The Globe and Mail reported in 1987, “(Bill C-31) appears to have placed between 50,000 and 100,000 native Canadian women in legal limbo” (Toronto Globe and Mail, October 16, 1987, as cited by Anderson & Robertson, 2011, p. 215).

Let’s look at a few more examples of gendered discrimination, particularly in the media. Given the media’s consistent history, from the writings of Columbus to Canada’s first newspaper, to the consistent hypersexualization of Indigenous women in media, Indigenous women have become targets for the colonial male imaginary. Nineteen-year-old Helen Betty Osborne was brutally murdered in 1971. She was killed at the hands of four white men who had been drinking heavily, who had intercepted her, brought her to a lake, and stabbed her to death with a screwdriver. She was found frozen in the lake. Osborne’s murder was glossed over in the media with only one newspaper article, but her death would later be subject to the 1991 Manitoba Aboriginal Justice Inquiry. Sixteen years after Osborne’s death, one man would be charged with her murder. The Inquiry concluded that the murderers “seemed to be operating on the assumption that Aboriginal women were promiscuous and open to enticement through alcohol or violence. The men who abducted Osborne believed that young Aboriginal women were objects with no human value beyond [their own] sexual gratification” (Razack, 2002, as cited by Anderson & Robertson, 2011, p. 201).

The inquiry determined that if Osborne were a non-Indigenous woman, the police would have worked harder to resolve the case. The same themes of racialized and gendered violence against Indigenous women, and the resultant lack of police investigation and downplaying of harms, can be found in the murder of a 28-year-old mother of two. In 1995, Pamela George was killed at the hands of two young white males, while the brutalities of the court case were unaddressed and downplayed in the media. In court, the judge reminded the jury that Pamela George was a sex worker, as a response to whether or not Pamela George could have consented to this murder. Yet Pamela George’s funeral was ultimately a closed-casket one. Those same media themes can be found in the reporting of a September, 2001 case in which a twelve-year-old from Yellow Quill First Nation had been gang raped by three white men in their 20s, who got her drunk and paraded her through bars. The media described her as the aggressor, despite her being a child targeted for sexual assault (Anderson & Robertson, 2011).

The same theme of police non-interest can be attributed to the mass murders of Indigenous women. The case of Robert Pickton, who in 2002 had been found to have killed more than 26 women, though he had admitted to killing 49 women, the majority of whom were Indigenous women, sex workers, and/or women with substance abuse. Here, Canada’s body politic, including its police force, has been criticized for its lack of action — continuing what Lawrence (2004) describes as the “extreme discursive warfare,” or that of media enabling state violence.

With social media came digitally-mediated social uprisings. In 2012, the hashtag #MMIW would take storm, and addressing the issue of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women would grow into a continental phenomenon. A 2014 report on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, conducted by the RCMP, determined that Indigenous men are the cause of most of the reported violence against Indigenous women. Eventually, then-Prime Minister Justin Trudeau initiated a National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, which provided a much more detailed account of the colonial histories of racialized, gendered, and sexualized violence against Indigenous women (National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, 2019).

The report illustrates a lack of media attention to Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, stating that such a “framing sends the message that Indigenous women, girls, and 2SLGBTQQIA people are not ‘newsworthy’ victims” (National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, 2019, p. 27). Calls to action from the MMIWG report are addressed in the next section.

News Coverage: Land Defence and Landmark Legal Cases (2016- now)

Drawing precedent from the coverage of Wounded Knee, the Alcatraz Occupation, Anicinaabe Park, and the Oka Crisis, news media rarely provides context for the reasons and rationale behind the protests. As Clark (2014) affirms, “the little media attention there is on Aboriginal peoples focuses on the actions of protest… versus the reasons for the protests” (Pierro et al., 2013, p. 12, as cited in Clark, 2014, p. 32).

The Keystone XL Pipeline, later renamed the Dakota Access Pipeline, has a shining spot in Canada’s media history. While the media covered the protests from 2014 to today, they hardly covered the rationale behind such dissent (Clark, 2014). These pipelines would go through Indigenous lands, with or without the consent of the Indigenous Peoples who already live there, endangering vital waterways. Where municipalities have vetoed pipeline intrusion on their lands, Indigenous Peoples were subject to economic provisions outlined in various treaties and federal legislation. As Clark (2014) identifies, among all major news networks, only one network, Global News, mentioned Treaty Rights (p. 129). These themes would re-emerge in further examples, such as Wet’suwet’en protests against unauthorized pipelines going through their lands since 2015, the Mi’kmaw Lobster Fishing protest in 2020, and the Fairy Creek Blockade in protest against old-growth logging in 2020 and 2021. As ironically addressed by the Yellowhead Institute, “Canada consistently ranks near the top of global newsprint and wood pulp production that derives from boreal forests” (Webster et al., 2015; Yellowhead Institute, 2019, p. 26).

While Indigenous protests often receive biased coverage without a description of the rationale, it is even harder to raise public dissent as an individual. The women behind advancing Bill C-31 were targeted individually. In September 2018, at the Inquiry for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Mi’gmaq researcher TJ Lightfoot brought attention to the gendered discrimination and violence at so-called “man camps” — labour camps with a majority of male labourers — which correlate with gendered and sexualized violence against Indigenous women of those lands. Like the women behind Bill C-31, Lightfoot “faced scrutiny in the media and subsequent personal attacks” by both the Nunavut and NWT Chambers of Mines (Yellowhead Institute, 2019, p. 29).

While Canada had committed to addressing ongoing gendered discrimination through the Indian Act, Sharon McIvor (a lead voice in the matter) was not given room for her inclusion in the discussions. Despite her involvement in the pinnacle legal case, McIvor v. Canada, and her lead in various international committees addressing such gendered discrimination against Indigenous women, she had not been included in discussions regarding revisions to the Indian Act. At such an exclusion, she referred to the United Nations, saying that Canada was still not upholding its international rights commitments, as maintained through gendered discrimination against Indigenous women through the Indian Act. The United Nations agreed, in 2019. The National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women would conclude in 2019, releasing further recommendations for media to be reviewed in the next chapter.

Using Style Guides and Training to Transform Indigenous Media Representations

For generations, Indigenous Peoples in Canada have been misrepresented, stereotyped, or altogether silenced by mainstream media systems that privileged colonial perspectives. This has shaped public attitudes, government policies, and everyday relationships, often to the detriment of Indigenous communities (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015). Conventional professional resources, such as the Canadian Press Stylebook and Caps and Spelling, have long served as references for spelling, grammar, and general usage. However, these guides alone do not address the nuanced cultural protocols, historical contexts, and ethical responsibilities necessary for covering Indigenous Peoples and stories with accuracy and respect (Younging, 2018).

Recognizing this gap, Indigenous-specific style guides have been developed to provide practical, community-informed tools for journalists, designers, filmmakers, and public relations practitioners. For journalism students, resources like the Style Guide for Reporting on Indigenous People (Journalists for Human Rights [JHR], 2017) and Elements of Indigenous Style (Younging, 2018) outline concrete steps to avoid common pitfalls such as pan-Indigenous generalizations, outdated terms, and reliance on non-Indigenous “experts.” For example, Younging (2018) recommends always identifying Indigenous individuals and communities by their specific nation names rather than generic labels like “Native” or “Aboriginal.” This small change demonstrates respect for identity and sovereignty, countering decades of homogenized coverage.

Information design students benefit from resources like the International Indigenous Design Charter (International Council of Design, 2018), which promotes protocols for co-creating visual materials with Indigenous communities and respecting Indigenous cultural and intellectual property rights. This means not simply incorporating Indigenous motifs as decoration but collaborating meaningfully with community members to ensure that symbols, language, and designs are contextually accurate and culturally appropriate. For example, a public health infographic targeting a specific First Nation should reflect that community’s visual language and be vetted by local knowledge keepers rather than using generic or pan-Indigenous imagery.

Broadcasting students face similar responsibilities when producing audio-visual stories. The On-Screen Protocols and Pathways guide (imagineNATIVE, 2019) is a comprehensive resource outlining how filmmakers and producers can work in partnership with First Nations, Métis, and Inuit communities throughout all stages of production. It highlights ethical practices such as obtaining free, prior, and informed consent, hiring Indigenous crew and talent, and ensuring that the final product does not distort or misrepresent cultural teachings. For instance, a documentary about Indigenous land defenders should prioritize Indigenous voices as narrators and decision-makers, rather than positioning non-Indigenous journalists as the sole interpreters of events.

Public relations professionals and students can draw from Turn Your Words Into Action (Canadian Public Relations Society [CPRS], 2021), which outlines how to craft communication strategies that respect Indigenous self-determination. This includes avoiding “token” consultation, avoiding deficit-focused narratives, and partnering with Indigenous organizations to co-create campaigns. For example, a PR team working on a tourism promotion should centre Indigenous-led tourism businesses and ensure stories are told by local community members, not just outside marketers (Rogers, 2020).

These guides and training resources have emerged alongside major social and political movements, including Idle No More and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. These have brought national attention to the harms caused by distorted or one-sided representations (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015). They demonstrate that respectful, accurate storytelling is a technical task and part of a broader reconciliation process, cultural revitalization, and rebuilding trust (Schulich School of Law, 2024).

Yet, despite this progress, challenges remain. Institutional inertia, resource limitations, and the persistence of harmful tropes continue to slow change. Transformation takes more than reading a style guide; sustained commitment is needed from individuals, newsrooms, design firms, production companies, and PR agencies. Emerging professionals must continually update their knowledge, build authentic relationships with Indigenous communities, and hold their workplaces accountable for meeting these standards in daily practice (Younging, 2018; CPRS, 2021)

When consistently applied, Indigenous style guides, training programmes, and culturally informed protocols empower communicators across disciplines to produce media that is factually correct, culturally safe, and community-driven. This is essential for dismantling centuries of colonial narratives and supporting Indigenous Peoples’ rights to tell their own stories, in their own ways, on their own terms.

Summary

This chapter has traced the troubling continuity of colonial representation of Indigenous Peoples in Canadian media across five centuries, from Columbus’ 1500 letter endorsing sexual slavery, to the mediated representations on contemporary digital platforms. Through examining key historical moments, from early colonial writings and newspaper coverage of the Louis Riel Rebellion to the Oka Crisis and recent pipeline protests, we have seen how the media has consistently served colonial interests by reducing Indigenous Peoples to harmful stereotypes.

The theoretical frameworks provided by Duncan McCue’s “4Ds” rule (drumming, dancing, drunk, dead), Emma LaRocque’s “civ/sav” binary, and Anderson and Robertson’s comprehensive newspaper analysis reveal persistent patterns of representation that legitimize ongoing dispossession and violence. Despite surface-level changes in terminology over time, the underlying colonial assumptions remain deeply embedded in media practices. The chapter has also highlighted the particular violence faced by Indigenous women through media representation, from Columbus’ brutal writings to inadequate contemporary coverage of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women.

However, the analysis documents significant shifts following movements like Idle No More and institutions like the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. The emergence of Indigenous style guides, journalism training programs, and increased awareness of representation issues suggests possibilities for transformation, though progress remains slow and requires sustained institutional commitment.

Key Takeaways

Key chapter takeaways include:

- Colonial narratives persist despite surface changes, from “savage” to “warrior,” underlying assumptions about Indigenous inferiority remain embedded in media coverage across centuries.

- Media representation has real-world consequences in that coverage directly influences policy decisions, public opinion, and Indigenous lives, from justifying bison decimation to inadequate responses to MMIWG cases.

- Systemic transformation is needed, not just awareness. For instance, while movements like Idle No More created some progress, meaningful change requires restructuring journalism and communication education and media institutions, not just sensitivity training.

The path forward demands more than awareness; it requires systemic change to ensure the media serves reconciliation rather than perpetuating the harmful colonial legacy this chapter documents.

Group Activity: Quote Hunt & Share

Group size: 7 groups of 5 students | Time: 50 minutes | Platform: Google Slides

The instructor creates a shared Google Slides presentation with seven blank slides and assigns groups:

Group Assignments (Using Chapter Subheadings):

- Group 1: “The First Writings About Indigenous Peoples in Europe (1492-1500s)”

- Group 2: “Early Colonization and Catechisms; Early Publishers and Anthropologists (1600s-1812)”

- Group 3: “Themes of Early News Media: Manifest Destiny, Cultural Hegemonization, and Racialization (1812-1885)”

- Group 4: “Reporting on the Louis Riel Rebellion (1885)”

- Group 5: “Treaties 8-11; Residential Schools; Gold, Oil, Diamonds (1885-1921)”

- Group 6: “Media Shift: Oka Crisis, RCAP, Idle No More, TRC (1990-2015)”

- Group 7: “News Coverage: Land Defence and Landmark Legal Cases (2016-now)”

Each group finds and adds to their slide:

- The biggest surprise in their section

- 2-3 examples of colonial language or changes that have taken place

- One-sentence summary of what their section shows about media patterns

Share phase: Each group reads their most shocking quote (10 minutes)

Pattern analysis: Looking at all slides, discuss what the progression from 1492 to present reveals about colonial media patterns (10 minutes)

Wrap-up (5 minutes)

Final question: Based on your findings, has media representation of Indigenous peoples fundamentally changed or stayed the same?

End-of-Chapter Activity (News Scan)

Indigenous Peoples in Canadian Media

Purpose:

This assignment helps you connect historical perspectives and media theories with contemporary developments, enhancing your ability to critically analyze how media representations of Indigenous Peoples continue to shape Canadian society and influence public opinion.

Using Google News, find a recent article (published in the last three months) about Indigenous Peoples in Canadian media. Possible topics include media coverage of protests, land defence, representation in mainstream versus Indigenous-owned media, legal cases, or coverage related to Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG).

In 250 words, respond to the following:

Summarize the Article (100–150 words)

- Provide the title, author, and date in APA format.

- Explain the article’s primary focus and significance.

- Identify key findings or arguments presented.

Connect to Chapter Themes (100–150 words)

- Relate the article to at least one key theme from this chapter (such as McCue’s “4Ds”, LaRocque’s “civ/sav” binary, cultural hegemonization, or the role of media in land defence and resistance).

- Analyze how the article illustrates continuity or change in how Indigenous Peoples are portrayed compared to historical patterns discussed in the chapter.

- Explain what the article suggests about the future trajectory of media representation of Indigenous Peoples in Canada.

Note: The full text of the article must be included upon submission as an Appendix for verification.

References

American Anthropological Association. (1998). Statement on race. American Anthropologist, 100(3), 712-713.

Anderson, M. C., & Robertson, C. L. (2011). Seeing red: A history of natives in Canadian newspapers. University of Manitoba Press.

Bryce, P. H. (1922). The story of a national crime: Being an appeal for justice to the Indians of Canada. James Hope & Sons.

Canadian Public Relations Society. (2021). Turn your words into action: An Indigenous style guide. https://cprstoronto.com/2021/08/05/turn-your-words-into-actions-an-indigenous-style-guide/

Carter, S. (1997). Capturing women: The manipulation of cultural imagery in Canada’s prairie west. McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Clark, B. (2014). Framing Canada’s Aboriginal peoples: A comparative analysis of Indigenous and mainstream television news. Canadian Journal of Native Studies, 34(2), 65–88.

Columbus, C. (1500). Letter to Doña Juana de la Torre. In J. B. Thatcher (Ed.), Christopher Columbus: His life, his works and his remains (Vol. 2, pp. 345-350). G. P. Putnam’s Sons.

Davin, N. F. (1879). Report on industrial schools for Indians and half-breeds. Department of the Interior.

Fee, M. (2015). Literary land claims: The “Indian land question” from Pontiac’s War to Attawapiskat. Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

Holmes, J. (1987). Bill C-31: Equality or disparity? The effects of the new Indian Act on Native women. Canadian Advisory Council on the Status of Women.

imagineNATIVE. (2019). On-screen protocols and pathways: A media production guide to working with First Nations, Métis and Inuit communities, cultures, concepts and stories. https://imaginenative.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/OSPP-Guide-EN.pdf

International Council of Design. (2018). International Indigenous design charter: Protocols for sharing Indigenous knowledge in professional design practice. https://www.theicod.org/storage/app/media/resources/International_IDC_book_small_web.pdf

Jenness, D. (1932). The Indians of Canada. National Museum of Canada.

Journalists for Human Rights. (2017). Style guide for reporting on Indigenous people. https://www.readthemaple.com/content/files/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/jhr2017-style-book-indigenous-people.pdf

Las Casas, B. de. (1992). A short account of the destruction of the Indies (N. Griffin, Trans.). Penguin Classics. (Original work published 1542)

LaRocque, E. (2010). When the other is me: Native resistance discourse, 1850-1990. University of Manitoba Press.

Lawrence, B. (2004). “Real” Indians and others : mixed-blood urban Native peoples and indigenous nationhood. Lincoln : University of Nebraska Press. https://archive.org/details/realindiansother0000lawr

McArthur, D., Jaccoud, M., & Finn, J. (1999). The media coverage of the Oka crisis. Journal of Canadian Studies, 34(1), 410-428.

McCue, D. (2014, January 29). What does it take for Aboriginal people to make the news? CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/what-it-takes-for-aboriginal-people-to-make-the-news-1.2514466

Morrisseau, M. (2022). Indigenous health and healing: Traditional knowledge and research. University of Manitoba Press.

National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. (2019). Reclaiming power and place: The final report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. https://www.mmiwg-ffada.ca/final-report/

Pierro, R., et al. (2013). Media representation of Indigenous peoples in Canada. Aboriginal Peoples Television Network.

Pongerard, J. (2018, September 20). “Early Inuit studies: Themes and transitions, 1850s-1980s.” History of Anthropology Review. https://histanthro.org/reviews/early-inuit-studies/

Razack, S. (2002). Race, space, and the law: Unmapping a white settler society. Between the Lines.

Rogers, R. (2020, January). 12 ways to better choose our words when we write about Indigenous Peoples. Indigenous Tourism Alberta. https://indigenoustourism.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/19-12-Style-Guide-Media-Version-v8-1.pdf

Schulich School of Law. (2024). Best practices for writing about Indigenous Peoples in the Canadian legal context: An evolving style guide. Dalhousie University. https://cttj.ca/images/StyleGuide_June2024.pdf

Scott, D. C. (1898). Onandaga Madonna. The Labour and Other Poems. Morang & Co.

Smedley, A. (1999). Race in North America: Origin and evolution of a worldview. Westview Press.

Thatcher, J. B. (1903). Christopher Columbus: His life, his works and his remains (Vol. 2). G. P. Putnam’s Sons.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future: Summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. McGill-Queen’s University Press.

United Nations Human Rights Committee. (2019, January 11). Views adopted by the Committee under article 5 (4) of the Optional Protocol, concerning communication No. 2020/2010. https://juris.ohchr.org/Search/Details/2549

Vowel, C. (2016). Indigenous writes: A guide to First Nations, Métis, and Inuit issues in Canada. Highwater Press.

Webster, K., Hamalé, D., & Graham, N. (2015). Indigenous peoples and forest certification: A review of the literature. Sustainable Forest Management Network.

Yellowhead Institute. (2019). Land back: A Yellowhead Institute red paper. Yellowhead Institute.

Younging, G. (2018). Elements of Indigenous style: A guide for writing by and about Indigenous peoples (2nd ed.). Brush Education.

Media Attributions

- Calgary Herald Front Page 1905-11-09

- oka crisis

- MMWIG